Crane (machine) facts for kids

A crane is a special machine that helps lift and move heavy things. It usually has ropes, chains, and wheels called sheaves. Cranes can lift objects up, lower them down, and even move them sideways. They are mostly used to lift very heavy items and carry them to different places.

Cranes use simple machines like pulleys to make lifting easier. This means they can move loads that are too heavy for people to lift alone. You often see cranes in places like construction sites, where they move building materials. They are also used in ports to load and unload ships, and in factories to assemble large equipment.

The very first crane was called the shaduf. It was invented in ancient Mesopotamia (which is now Iraq) around 3000 BC. Later, the ancient Egyptians also used it to lift water. The ancient Greeks then created cranes for building. These early cranes were powered by people or animals like donkeys. The Roman Empire developed even bigger cranes. They used large human-powered treadwheels to lift heavier weights.

During the High Middle Ages, cranes were used in harbors to load and unload ships. Some were even built into strong stone towers. The first cranes were made of wood. But during the Industrial Revolution, people started using stronger materials like cast iron, iron, and steel.

For a long time, people or animals provided the power for cranes. But then, the first mechanical power came from steam engines. The earliest steam cranes appeared in the 18th or 19th century. Many of these were still used until the late 1900s. Today, most modern cranes use internal combustion engines or electric motors. They also use hydraulic systems. These modern cranes can lift much heavier loads than ever before. However, simple manual cranes are still used in places where it's not practical to have power.

There are many different kinds of cranes. Each one is designed for a special job. Some are small, like the jib cranes used inside workshops. Others are huge, like the tower cranes that build very tall skyscrapers. Mini-cranes are also used for high buildings. They can reach small, tight spaces. Large floating cranes are often used to build oil rigs or to rescue sunken ships.

Some lifting machines are called cranes, even if they don't exactly fit the main definition. Examples include stacker cranes and loader cranes.

Contents

- What's in a Name? The Word "Crane"

- How Cranes Were Invented: A Look at History

- How Cranes Work: Mechanical Principles

- Different Kinds of Cranes

- Mobile Cranes: Cranes on the Move

- Fixed Cranes: Staying in One Place

- Crane Operators: The People Behind the Lifts

- Images for kids

- See also

What's in a Name? The Word "Crane"

Cranes got their name because they look a bit like the long neck of the crane bird. In ancient Greek, the word for crane was geranós. In French, it's grue.

How Cranes Were Invented: A Look at History

Early Cranes in the Ancient World

The very first type of crane was the shadouf. It had a lever system and was used to lift water for watering crops. It was invented in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) around 3000 BC. The shadouf later appeared in ancient Egyptian technology around 2000 BC.

Ancient Greek Lifting Machines

The Ancient Greeks developed a crane for lifting heavy loads in the late 6th century BC. Archaeologists have found special holes in stone blocks from Greek temples. These holes show that a lifting device was used. They are either above the center of the stone or in pairs around it. This is proof that cranes existed.

Soon, the Greeks started using winches and pulleys. This made it easier to lift things straight up. Before, they used ramps. For the next 200 years, Greek builders used many smaller stones instead of a few large ones. This was because the new lifting method made it more practical. For example, Greek temples like the Parthenon used stone blocks that weighed less than 15–20 tons. They also stopped using huge single columns. Instead, they used several column pieces.

We don't know exactly how cranes replaced ramps. But some believe that Greece's changing society made cranes more useful. Small, skilled building teams preferred cranes over the large, unskilled workforces needed for ramps in places like Egypt or Assyria.

The first clear written evidence of a system with multiple pulleys comes from a book called Mechanical Problems. It was written around the time of Aristotle (384–322 BC). Around this time, the size of stone blocks in Greek temples started to get bigger again. This suggests that more advanced pulley systems were being used.

Roman Empire: Bigger and Better Cranes

Cranes were most popular in ancient times during the Roman Empire. Building projects were huge, and buildings became enormous. The Romans took the Greek crane and made it even better. We know a lot about their lifting methods from engineers like Vitruvius and Hero of Alexandria. There are also two old pictures of Roman treadwheel cranes. One on the Haterii tombstone from the late first century AD is very detailed.

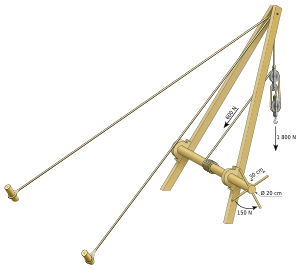

The simplest Roman crane was called the trispastos. It had a single arm, a winch, a rope, and a block with three pulleys. With this setup, one person working the winch could lift about 150 kg (3 pulleys x 50 kg per person).

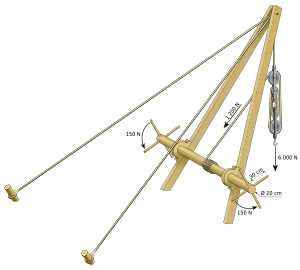

Heavier cranes had five pulleys (pentaspastos). The largest one, the Polyspastos, had three sets of five pulleys. It could have two, three, or four masts, depending on how much it needed to lift. If four men worked the winch on a polyspastos, they could easily lift 3,000 kg. If a large treadwheel replaced the winch, the crane could lift twice as much, up to 6,000 kg, with only half the people. This was because the treadwheel had a much greater mechanical advantage.

This meant Roman cranes were very efficient. For example, to move a 2.5-ton stone block up a ramp for the pyramids, about 50 men were needed. But the Roman polyspastos could lift 3,000 kg per person, which was 60 times more efficient!

However, many Roman buildings have stone blocks much heavier than what a single polyspastos could lift. For instance, at the temple of Jupiter in Baalbek, some stone blocks weigh up to 60 tons. One corner block is even over 100 tons! All these were lifted about 19 meters high. In Rome, the top block of Trajan's Column weighs 53.3 tons and was lifted about 34 meters high.

Historians believe Roman engineers lifted these super-heavy weights using two methods. First, they set up a lifting tower, like a siege tower, with the column in the middle. Second, they used many capstans on the ground around the tower. Capstans had less leverage than treadwheels, but more men (or even animals) could operate them. This use of many capstans is mentioned when the Lateranense obelisk was lifted in Rome around 357 AD. Lifting such heavy weights needed a lot of teamwork and coordination.

Cranes in the Middle Ages

During the High Middle Ages, the treadwheel crane came back into use in Europe. It had been forgotten after the Western Roman Empire fell. The first mention of a treadwheel in writing is from France around 1225. A drawing of one appeared in a French book around 1240. The first uses of harbor cranes are recorded in cities like Utrecht (1244), Antwerp (1263), Bruges (1288), and Hamburg (1291). In England, the treadwheel was not recorded until 1331.

Cranes made vertical transport safer and cheaper than older methods. They were used in harbors, mines, and especially on building sites. The treadwheel crane was very important for building tall Gothic cathedrals. However, old and new machines still existed side-by-side. Things like ladders and wheelbarrows were still used alongside cranes.

Besides treadwheels, medieval drawings also show cranes powered by hand-cranked windlasses. By the 15th century, some windlasses looked like a ship's wheel. To make lifting smoother, flywheels were used as early as 1123.

We don't know exactly how the treadwheel crane was brought back. But its return is linked to the rise of Gothic architecture. It might have developed from the windlass. Or, it could have been a new invention inspired by Roman cranes described in old books. The idea might also have come from observing waterwheels, which had similar parts.

How Medieval Cranes Were Built and Used

The medieval treadwheel was a large wooden wheel. It turned around a central shaft. The inside of the wheel was wide enough for two workers to walk side by side. Early wheels had spokes directly connected to the shaft. Later, more advanced wheels had arms arranged differently, allowing for a thinner shaft and better lifting power.

Many people think medieval cranes were placed on light scaffolding or thin church walls. But this is not true. These structures couldn't hold the weight of the crane and its load. Instead, cranes were first set up on the ground, often inside the building. When a new floor was finished, the crane was taken apart. Then, it was rebuilt on the roof beams. From there, it moved along as the building's vaults were constructed. So, the crane "grew" and "moved" with the building. That's why today, all existing construction cranes in England are found in church towers. They stayed there after construction to help with repairs.

Sometimes, medieval pictures also show cranes attached to the outside of walls.

How Medieval Cranes Worked

Unlike modern cranes, medieval cranes mostly lifted things straight up. They weren't used to move loads long distances horizontally. So, lifting work was organized differently. For example, in building construction, the crane would lift stone blocks directly into place. Or, it would lift them to a central spot on the wall. From there, two teams could move the blocks to each end of the wall. The crane operator could also move the load sideways a little using a small rope. Cranes that could rotate the load appeared around 1340. These were very useful for working at docks. Stone blocks were lifted directly with slings or special clamps. Other items were placed in containers like pallets, baskets, or barrels.

It's interesting that medieval cranes rarely had ratchets or brakes to stop the load from falling backward. This is because the medieval tread-wheels created a lot of friction. This usually stopped the wheel from spinning out of control.

Cranes in Harbors

Stationary harbor cranes were a new invention of the Middle Ages. They were not known in ancient times. A typical harbor crane could pivot and had double treadwheels. These cranes were placed at docks to load and unload ships. They replaced or helped older methods like see-saws and winches.

There were two main types of harbor cranes. Gantry cranes, which turned on a central pole, were common in Belgium and the Netherlands. German harbors usually had tower cranes. In these, the windlass and treadwheels were inside a strong tower. Only the arm and roof rotated. Dockside cranes were not used in the Mediterranean region or in Italy's advanced ports. They continued to unload goods using ramps for a long time.

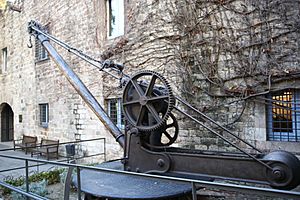

Harbor cranes often had double treadwheels to speed up loading. This was because the work speed was not limited by masons, as it was with construction cranes. The two treadwheels were about 4 meters or more in diameter. They were attached to each side of the axle and turned together. They could lift 2–3 tons, which was the usual size of ship cargo. Today, there are still fifteen treadwheel harbor cranes from before the Industrial Revolution in Europe. Some harbor cranes were specialized. They were used to put masts on new sailing ships, like in Gdańsk, Cologne, and Bremen. Besides these fixed cranes, floating cranes also started to be used by the 14th century. These could be moved anywhere in the port.

Cranes in the Early Modern Age

A lifting tower, similar to those used by the ancient Romans, was used by the Renaissance architect Domenico Fontana in 1586. He used it to move the 361-ton Vatican obelisk in Rome. His reports show that coordinating the lift needed a lot of focus and discipline. If the force wasn't applied evenly, the ropes could break.

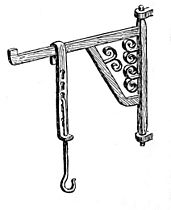

Cranes were also used in homes during this time. A chimney or fireplace crane was used to swing pots and kettles over the fire. Their height could be adjusted with a trammel.

- Examples of early modern cranes

-

An 1868 photo of a 15th-century crane on the unfinished south tower of Cologne Cathedral

The Industrial Revolution and Modern Cranes

With the start of the Industrial Revolution, the first modern cranes were installed in harbors to load cargo. In 1838, the inventor William Armstrong designed a water-powered hydraulic crane. His design used water pressure to push a part called a ram. This ram then pulled a chain to lift the load.

In 1845, a plan was made to bring piped water to homes in Newcastle. Armstrong was part of this plan. He suggested using the extra water pressure in the lower part of town to power one of his hydraulic cranes. This crane would load coal onto boats. He said his invention would be faster and cheaper. The city agreed, and the experiment worked so well that three more hydraulic cranes were installed.

Because his hydraulic crane was so successful, Armstrong started a company called Elswick works in Newcastle in 1847. His company made hydraulic machines for cranes and bridges. Soon, they received orders from many places. The company grew from 300 workers making 45 cranes a year in 1850 to almost 4,000 workers making over 100 cranes a year by the early 1860s.

Armstrong kept making his crane design better. His most important invention was the hydraulic accumulator. If there wasn't enough water pressure on site for hydraulic cranes, Armstrong often built tall water towers. But when supplying cranes for New Holland, he couldn't build a tower because the ground was sandy. So, he invented the hydraulic accumulator. This was a heavy cylinder with a plunger. The plunger would slowly rise, pulling in water. Then, its weight would push the water out at high pressure. This invention allowed much more water to be pushed through pipes at a constant pressure. This greatly increased the crane's lifting power.

One of his cranes, built for the Italian Navy in 1883, is still standing in Venice. It was used until the mid-1950s.

How Cranes Work: Mechanical Principles

There are three main things to think about when designing cranes:

- The crane must be able to lift the weight of the load.

- The crane must not fall over.

- The crane's parts must not break.

- Examples of Mechanical principles

Keeping a Crane Stable

To stay stable, all the forces trying to tip the crane over must be balanced. In simple terms, the crane must not overturn. The maximum weight a crane is allowed to lift (called the "rated load") is always less than the weight that would make it tip. This provides a safety margin.

For mobile cranes in the United States, the safe lifting limit for a crawler crane is 75% of the tipping load. For a mobile crane on outriggers, it's 85% of the tipping load. These rules help make sure cranes are safe.

Cranes on ships or offshore platforms have even stricter rules. This is because the ship's movement can affect the crane. Also, the stability of the ship itself must be considered.

For cranes fixed to a base, the weight of the arm and load is held by the base. The stress on the base must be less than what the material can handle, or the crane will break.

Different Kinds of Cranes

Mobile Cranes: Cranes on the Move

There are four main types of mobile cranes: truck-mounted, rough-terrain, crawler, and floating cranes.

Truck-Mounted Cranes

The simplest truck-mounted crane is a "boom truck" or "lorry loader." It has a crane with a telescoping arm mounted on the back of a regular truck. This arm can rotate.

Larger, heavier truck-mounted cranes are built in two parts. The bottom part is the "carrier" or "lower." The top part is the "lifting component" or "upper," which includes the boom. These two parts are connected by a turntable, allowing the top part to swing around. Modern hydraulic truck cranes usually have one engine that powers both the truck and the crane. The crane part gets its power from hydraulics that run through the turntable. Older designs had two engines, one for the truck and one for the crane.

These cranes can usually drive on highways. This means they don't need special transport unless they are too heavy or big for local laws. If they are too big, they might use special trailers to spread the weight. Or, they can be taken apart. For example, the counterweights are often removed and carried by another truck. Some cranes can even remove the entire upper part. When working, outriggers extend from the truck to level and stabilize the crane. Many truck cranes can move slowly while carrying a load. But you have to be very careful not to swing the load sideways, as this can make the crane unstable. Most of these cranes also have moving counterweights for extra stability. Crane operators use special charts or electronic systems to know the maximum safe loads.

Truck cranes can lift from about 14.5 tons to about 2240 tons. Most can only rotate about 180 degrees, but more expensive ones can turn a full 360 degrees.

- Examples of truck mounted cranes

Rough Terrain Cranes

A rough terrain crane has a boom mounted on a base with four rubber tires. It's designed to work off-road and can pick up and carry loads. Outriggers are used to level and stabilize the crane when it's lifting.

These cranes have a telescoping boom. They are single-engine machines, meaning the same engine powers both the crane and the wheels, similar to a crawler crane. The engine is usually in the base, not the top part. Most have 4-wheel drive and 4-wheel steering. This helps them move on rough or slippery ground more easily than a standard truck crane.

Crawler Cranes

A crawler crane has its boom mounted on a base with crawler tracks. These tracks provide both stability and movement. Crawler cranes can lift from about 40 to 4000 tons.

The main benefit of a crawler crane is that it can move easily and work on sites with little preparation. It's stable on its tracks without needing outriggers. The wide tracks spread the weight over a large area, so they are much better than wheels at moving on soft ground without sinking. A crawler crane can also travel while carrying a load. Its main downside is its weight. This makes it hard and expensive to transport. Large crawler cranes usually have to be taken apart (at least the boom and cab) and moved by trucks, trains, or ships to their next job.

Floating Cranes

Floating cranes are mainly used for building bridges and ports. They also load and unload very heavy or awkward items from ships. Some floating cranes are on pontoons. Others are special crane barges that can lift over 10,000 tons. They have been used to move entire bridge sections. Floating cranes are also used to rescue sunken ships.

Crane vessels are often used in offshore construction. The largest rotating cranes are on the SSCV Sleipnir. It has two cranes, each able to lift 10,000 tons. For 50 years, the largest such crane was "Herman the German." It was one of three built by Nazi Germany and captured in the war. This crane was sold to the Panama Canal in 1996 and is now called Titan.

Other Mobile Crane Types

Reach Stackers

A reach stacker is a vehicle that handles cargo containers in small terminals or medium-sized ports. Reach stackers can quickly move containers short distances and stack them in different rows.

All-Terrain Cranes

An all-terrain crane is a mix of a truck-mounted crane and a rough-terrain crane. It can travel fast on public roads and also move well on rough ground at the job site. It uses all-wheel steering.

These cranes have 2 to 12 axles. They are designed to lift loads up to 2000 tons.

Pick and Carry Cranes

A pick and carry crane is like a mobile crane because it can travel on public roads. However, these cranes don't have stabilizer legs or outriggers. They are designed to lift a load, carry it a short distance to its destination, and then drive to the next job. Pick and carry cranes are popular in Australia, where job sites are far apart. One popular maker was Franna, which is now owned by Terex. Many people still call all pick and carry cranes "Frannas," even if they are made by other companies. Almost every medium- and large-sized crane company in Australia has at least one. The lifting capacity is between 10 and 40 tons, but this is much less if the load is far from the front of the crane. Pick and carry cranes have taken over work that smaller truck cranes used to do, because they set up much faster. Many steel factories also use them. They can "walk" with steel parts and place them easily.

Sidelifter Cranes

A sidelifter crane is a truck or semi-trailer that can lift and transport standard containers. It uses parallel crane-like hoists to lift a container from the ground or from a train car.

Carry Deck Cranes

A carry deck crane is a small 4-wheel crane. It has a boom that rotates 360 degrees, placed right in the center. The operator's cab is at one end under the boom. The engine is in the back. The area above the wheels is a flat deck. This is an American invention. The Carry Deck can lift a load in a small space and then put it on the deck around the cab or engine. Then, it can move to another site. The Carry Deck is the American version of the pick and carry crane. Both allow the crane to move the load short distances.

Telescopic Handlers

Telescopic handlers are like forklifts. They have forks mounted on a telescoping boom, like a crane. Early telescopic handlers only lifted in one direction and didn't rotate. However, some makers have designed telescopic handlers that rotate 360 degrees using a turntable. These machines look almost like rough terrain cranes. These new 360-degree models have outriggers or stabilizer legs that must be lowered before lifting. Their design is simpler, so they can be set up faster. These machines are often used to handle pallets of bricks and install roof trusses on new buildings. They have taken over much of the work for small telescopic truck cranes. Many armies around the world have bought telescopic handlers, including the more expensive rotating types. Their ability to go off-road and their versatility to unload pallets or lift like a crane make them very useful.

Harbor Cranes

These cranes handle dry bulk cargo or containers. They are usually found in bay areas or along inland waterways.

Travel Lifts

A travel lift (also called a boat gantry crane) is a crane with two rectangular side panels joined by a beam at the top. The crane is mobile with four groups of steerable wheels, one on each corner. These cranes allow boats with masts or tall structures to be taken out of the water and moved around docks or marinas.

Railroad Cranes

A railroad crane has special wheels that fit on railroad tracks. The simplest kind is a crane mounted on a flatcar. More advanced ones are built just for railroads. Different types of cranes are used for track maintenance, rescuing trains, and loading freight in goods yards.

Aerial Cranes

Aerial cranes, or "sky cranes," are usually helicopters designed to lift large loads. Helicopters can reach and lift in areas that regular cranes can't. Helicopter cranes are often used to lift things onto shopping centers and tall buildings. They can lift anything within their capacity, like air conditioning units, cars, boats, or swimming pools. They also help with disaster relief after natural disasters and carry huge buckets of water to fight wildfires.

Some aerial cranes, mostly ideas, have also used lighter-than-air aircraft, like airships.

Climbing Cranes

Instead of setting up a large crane to build a wind turbine tower, a smaller climbing crane can help. It builds the tower, climbs with it to the top, lifts the generator, adds the rotor blades, and then climbs down. This idea was introduced by Lagerwey Wind and Enercon.

Straddle Carriers

A Straddle carrier moves and stacks intermodal containers.

Fixed Cranes: Staying in One Place

These cranes are fixed in one spot, which allows them to lift heavier loads and reach greater heights. While they don't move during use, many can still be put together and taken apart.

Ring Cranes

Ring cranes are some of the largest and heaviest land-based cranes ever made. A ring-shaped track supports the main part of the crane. This allows them to lift extremely heavy loads, sometimes thousands of tons.

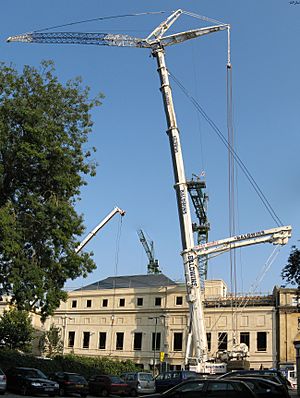

Tower Cranes

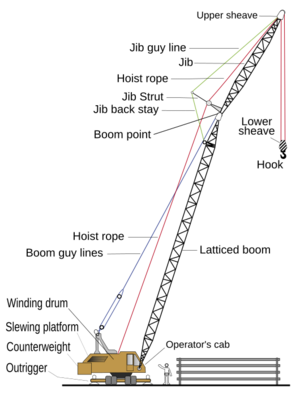

Tower cranes are a modern type of balance crane. They are fixed to the ground on a concrete base (and sometimes attached to the sides of buildings). Tower cranes often offer the best combination of height and lifting power. They are used to build tall buildings. The base is connected to the mast, which gives the crane its height. The mast is then connected to the slewing unit (gears and motor), which lets the crane rotate. On top of the slewing unit are three main parts: the long horizontal jib (working arm), the shorter counter-jib, and the operator's cab.

Choosing the best spot for a tower crane on a construction site is important. It helps reduce the cost of moving materials.

The long horizontal jib is the part that carries the load. The counter-jib holds heavy concrete blocks called counterweights. These balance the weight of the load. The crane operator either sits in a cab at the top of the tower or controls the crane with a remote control from the ground. The lifting hook is moved by electric motors using wire ropes and pulleys. The hook is on the long horizontal arm.

To hook and unhook loads, the operator usually works with a signaller (also called a "dogger" or "rigger"). They often talk by radio and always use hand signals. The rigger tells the crane operator what to lift and when. They are also responsible for the safety of the rigging and loads.

Tower cranes can reach a height of over 100 meters.

- Examples of tower cranes

-

Tower crane atop Mont Blanc

Parts of a Tower Crane

Tower cranes are used a lot in construction to lift and move materials. There are many types, but their main parts are similar:

- Mast: This is the main supporting tower. It's made of steel sections connected during setup.

- Slewing unit: This sits on top of the mast. It's the engine that makes the crane rotate.

- Operating cabin: On most tower cranes, the cabin is just above the slewing unit. It has the controls, load display, and other tools.

- Jib: This is the working arm that extends horizontally. A "luffing" jib can move up and down. A fixed jib has a trolley that moves along its underside to move goods horizontally.

- Counter jib: This holds the counterweights, the hoist motor, and other electronics.

- Hoist winch: This part lifts the load. It includes the motor, gearbox, drum, rope, and brakes. Many tower cranes have multiple speeds.

- Hook: The hook connects the material to the crane. It hangs from the hoist rope.

- Weights: Large, movable concrete counterweights are placed at the back of the counter-jib. They balance the weight of the lifted goods and keep the crane stable.

Setting Up a Tower Crane

A tower crane is usually put together by a telescopic (mobile) crane that has a longer reach. For very tall skyscrapers, a smaller crane might be lifted to the roof of the finished building to take the tower crane apart afterward. This can be harder than setting it up.

Tower cranes can be controlled remotely. This means the operator doesn't have to sit in the cab at the top.

How a Tower Crane Operates

Each tower crane model has a chart that shows how much it can lift at different distances from its center. Like a mobile crane, a tower crane can lift a much heavier object closer to its center than at its maximum reach. An operator uses levers and pedals to control each part of the crane.

Tower Crane Safety

When a tower crane is near buildings, roads, power lines, or other cranes, a tower crane anti-collision system is used. This system helps the operator avoid dangerous crashes. In some countries, like France, these systems are required by law.

Self-Erecting Tower Cranes

Self-erecting tower cranes are usually operated by a person on the ground. They are transported as a single unit and can be put together by a trained technician without a larger mobile crane. They rotate from the bottom and stand on outriggers. They don't have a counter-jib, and their counterweights are at the base of the mast. They cannot climb higher on their own and have less lifting power than standard tower cranes. They rarely have an operator's cabin.

Sometimes, smaller self-erecting tower cranes have axles permanently attached to the tower. This makes them easier to move around a job site.

Tower cranes can also use a hydraulic jack system to raise themselves. This allows them to add new tower sections without help from other cranes after the first setup. This is how they can grow to almost any height needed to build the tallest skyscrapers, by being tied to the building as it rises. The maximum height a tower crane can stand without support is about 265 feet.

Telescopic Cranes

A telescopic crane has a boom made of several tubes that fit inside each other. A hydraulic cylinder or other powered system extends or pulls back these tubes to make the boom longer or shorter. These booms are often used for short construction jobs, rescue operations, or lifting boats in and out of the water. Their compact size makes them good for many mobile uses.

While not all telescopic cranes are mobile, many are mounted on trucks.

A telescopic tower crane has a telescopic mast and often a top structure (jib) that makes it work like a tower crane. Some even have a telescopic jib.

Hammerhead Cranes

The "hammerhead," or giant cantilever, crane is a fixed-arm crane. It has a steel tower with a large, horizontal, double arm that rotates. The front part of this arm (the jib) carries the lifting trolley. The jib extends backward to support the machinery and counterbalancing weight. Besides lifting and rotating, it can also move the lifting trolley along the jib without changing the load's height. This horizontal movement of the load was a key feature in later crane designs. These cranes are usually very large and can weigh up to 350 tons.

The design of the Hammerkran first appeared in Germany around the early 1900s. It was then used and developed in British shipyards to help build battleships from 1904 to 1914. Hammerhead cranes could lift heavy weights. This was useful for installing large parts of battleships, like armour plate and gun barrels. Giant cantilever cranes were also installed in naval shipyards in Japan and the United States. The British government also installed one at the Singapore Naval Base (1938) and later a copy at Garden Island Naval Dockyard in Sydney (1951). These cranes helped repair the battle fleet far from Great Britain.

In the British Empire, the company Sir William Arrol & Co. was the main maker of giant cantilever cranes. They built 14 in total. Few of the 60 built worldwide still exist today. Seven are in England and Scotland.

The Titan Clydebank is one of four Scottish cranes on the River Clyde. It is now kept as a tourist attraction.

Level Luffing Cranes

Normally, when a crane with a hinged arm (jib) moves its arm up or down (luffs), its hook also moves up and down. A level luffing crane is a crane of this design, but it has an extra system to keep the hook at the same level when the arm moves.

Overhead Cranes

An overhead crane, also known as a bridge crane, has a hook and line system that runs along a horizontal beam. This beam itself runs along two widely separated rails. Often, it's in a long factory building and runs along rails on the two long walls. It's similar to a gantry crane. Overhead cranes usually have either a single beam or a double beam. These can be made from typical steel beams or a more complex box shape. The picture shows a single bridge box girder crane with the hoist controlled by a wired button station. Double girder bridges are more common for heavier systems, from 10 tons and up. The box girder design is lighter but stronger overall. It also includes a hoist to lift items, the bridge that spans the area, and a trolley to move along the bridge.

Overhead cranes are most commonly used in the steel industry. At every step of making steel, from raw materials to finished product, an overhead crane handles it. Raw materials are poured into a furnace by crane. Hot steel is stored for cooling by an overhead crane. Finished coils are lifted and loaded onto trucks and trains by overhead crane. Factories that shape metal also use overhead cranes to handle the steel. The automobile industry uses overhead cranes for raw materials. Smaller workstation cranes handle lighter loads in a work area, like near a CNC machine.

Almost all paper mills use bridge cranes for regular maintenance. They need to remove heavy press rolls and other equipment. Bridge cranes are used when paper machines are first built. They help install heavy cast iron drying drums and other huge equipment, some weighing as much as 70 tons.

In many cases, the cost of a bridge crane can be saved by not having to rent mobile cranes. This is true when building a facility that uses a lot of heavy equipment.

Electric Overhead Traveling Cranes

This is the most common type of overhead crane. You can find them in many factories. These cranes are run by electricity. They are controlled by a button station, a remote control, or from an operator's cabin attached to the crane.

Gantry Cranes

A gantry crane has a hoist in a fixed house or on a trolley. This trolley runs horizontally along rails, usually on one or two beams. The crane frame is supported by a gantry system with wheels that run on a gantry rail. These cranes come in all sizes. Some can move very heavy loads, especially the huge ones used in shipyards or factories. A special type is the container crane (or "Portainer" crane). It's designed for loading and unloading ship containers at a port.

Most container cranes are this type.

Deck Cranes

These cranes are found on ships and boats. They are used for loading and unloading cargo or for putting boats in and out of the water when there are no shore facilities. Most are powered by diesel-hydraulics or electric-hydraulics.

Jib Cranes

A jib crane has a horizontal arm (jib or boom) that supports a movable hoist. This arm is fixed to a wall or a pillar on the floor. Jib cranes are used in factories and on military vehicles. The arm can swing in a circle for more side-to-side movement, or it can be fixed. Similar cranes, often just called hoists, were put on the top floors of warehouse buildings. They allowed goods to be lifted to all floors.

Bulk-Handling Cranes

Bulk-handling cranes are designed from the start to carry a grab or bucket. They don't use a hook and sling. They are used for bulk materials like coal, minerals, or scrap metal.

Loader Cranes

A loader crane (also called a knuckle-boom crane or articulating crane) is a hydraulic arm attached to a truck or trailer. It's used for loading and unloading the vehicle's cargo. Its many jointed sections can fold into a small space when not in use. One or more sections might be telescopic. Often, the crane can do some tasks automatically, like unloading itself without the operator's direct instruction.

Unlike most cranes, the operator often has to move around the vehicle to see the load. So, modern cranes might have a portable control system (wired or radio) to help.

In the UK and Canada, this type of crane is often called a "Hiab." This is partly because Hiab invented the loader crane and was the first to sell it in the UK. Also, their name was clearly displayed on the crane arm.

A rolloader crane is a loader crane mounted on a chassis with wheels. This chassis can ride on the trailer. Because the crane can move on the trailer, it can be a lighter crane. This allows the trailer to carry more goods.

Stacker Cranes

A crane with a forklift-like system is used in automated (computer-controlled) warehouses. This is part of an automated storage and retrieval system (AS/RS). The crane moves on a track in a warehouse aisle. The fork can go up or down to any level of a storage rack. It can also extend into the rack to store and get products. Sometimes, the product can be as big as a car. Stacker cranes are often used in large freezer warehouses for frozen food. This automation means forklift drivers don't have to work in freezing temperatures every day.

Block-Setting Cranes

A block-setting crane is a type of crane used for installing large stone blocks. These blocks were used to build breakwaters, moles, and stone piers.

Crane Operators: The People Behind the Lifts

Crane operators are skilled workers who operate heavy equipment.

Key skills needed for a crane operator include:

- Understanding how to use and take care of machines and tools.

- Good teamwork skills.

- Attention to details.

- Good spatial awareness (knowing where things are in space).

- Patience and the ability to stay calm in stressful situations.

Images for kids

-

An 1868 photo of a 15th-century crane on the unfinished south tower of Cologne Cathedral

See also

In Spanish: Grúa (máquina) para niños

In Spanish: Grúa (máquina) para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |