Marc Isambard Brunel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir

Marc Isambard Brunel

FRS FRSE

|

|

|---|---|

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel,

by James Northcote |

|

| Born |

Marc Isambard Brunel

25 April 1769 Hacqueville, Normandy, France

|

| Died | 12 December 1849 (aged 80) Westminster, London, England

|

| Resting place | Kensal Green Cemetery |

| Nationality |

|

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Known for | Thames Tunnel |

| Spouse(s) |

Sophia Kingdom

(m. 1799) |

| Children |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

French Navy |

| Years of service | 1786–1792 |

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (born April 25, 1769 – died December 12, 1849) was a brilliant French-British engineer. He is most famous for his amazing work in Britain. He built the Thames Tunnel, a huge project under a river. He was also the father of another famous engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Born in France, Brunel had to leave during the French Revolution. He moved to the United States in 1793. In 1796, he became the Chief Engineer of New York City. Later, in 1799, he moved to London, England, and married Sophia Kingdom. Besides the Thames Tunnel, he designed special machines. These machines could automatically make pulley blocks for the British Navy.

Brunel actually preferred his middle name, Isambard. But history usually calls him Marc. This helps avoid confusion with his more famous son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Contents

Early Life in France

Marc Brunel was the second son in his family. His father, Jean Charles Brunel, was a successful farmer in Hacqueville, France. Marc was born on the family farm. Usually, the second son in a wealthy family would become a priest. So, Marc started learning classical subjects like Greek and Latin.

But Marc didn't like those subjects. Instead, he was very good at drawing and math. He also loved music from a young age. When he was eleven, he went to a school in Rouen. The head of the school let him learn carpentry. He quickly became skilled, like a cabinetmaker. He also enjoyed sketching ships in the local harbor.

Since he didn't want to be a priest, his father sent him to live with relatives in Rouen. There, a family friend taught him about ships and naval matters. In 1786, Marc joined the French navy as a cadet. He traveled to the West Indies several times during his service. He even made his own octant, a tool for navigation, from brass and ivory.

In 1789, while Marc was away, the French Revolution began. In 1792, his ship finished its service, and Marc returned to Rouen. He supported the King, like many people in his area. In 1793, he visited Paris during the trial of King Louis XVI. Marc bravely spoke out against one of the Revolution's leaders, Robespierre. He was lucky to escape Paris safely.

It became clear that Marc had to leave France. While in Rouen, he had met Sophia Kingdom, a young English woman working as a governess. He had to leave her behind when he fled to Le Havre. He boarded an American ship called Liberty and sailed for New York.

Adventures in the United States

Marc Brunel arrived in New York on September 6, 1793. He then traveled to Philadelphia and Albany. He got involved in a plan to build a canal connecting the Hudson River to Lake Champlain. He also sent in a design for the new Capitol building in Washington. The judges liked his design, but it wasn't chosen.

In 1796, Brunel became an American citizen. He was then named Chief Engineer for New York City. He designed many buildings, including houses, docks, and a cannon factory. Sadly, most records of his work in New York were lost later.

In 1798, during a dinner, Brunel learned about a big problem for the Royal Navy. They needed 100,000 pulley blocks every year. These were used on sailing ships and were all made by hand. Brunel quickly thought of a way to use machines to make them automatically. He decided to go to England to show his invention to the Admiralty. He sailed on February 7, 1799, and arrived in England a month later.

Life and Work in Britain

While Brunel was in America, Sophia Kingdom had stayed in Rouen. During a dangerous time called the Reign of Terror, she was arrested. She was accused of being an English spy and feared for her life. Luckily, she was saved when Robespierre lost power in 1794. In 1795, Sophia was able to leave France and travel to London.

When Brunel arrived in England, he immediately went to London to find Sophia. They married on November 1, 1799. They had three children: Sophia (born 1801), Emma (born 1804), and their famous son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel (born 1806).

In 1799, Brunel met Henry Maudslay, a skilled engineer. Maudslay built working models of Brunel's machines for making pulley blocks. Brunel showed his idea to Samuel Bentham, a naval official. In 1802, Bentham suggested installing Brunel's machines at Portsmouth Block Mills. Brunel's machines were amazing! Unskilled workers could use them to make blocks ten times faster than before.

Forty-five machines were installed at Portsmouth. By 1808, they were making 130,000 blocks each year. Brunel had spent a lot of his own money on the project. It took a while, but the Admiralty finally paid him for his invention.

Brunel was a very talented mechanical engineer. He also worked on sawmill machinery. He built a sawmill in London to make thin sheets of wood called veneers. He also designed machines to mass-produce soldiers' boots. But the demand for boots ended when the Napoleonic Wars finished. In 1814, Brunel became a member of the Royal Society, a group of important scientists.

Facing Financial Trouble

Brunel sometimes got involved in projects that didn't make money. By 1821, he was deeply in debt. In May of that year, he was sent to King's Bench Prison. This was a special prison for people who couldn't pay their debts. Prisoners were allowed to have their families with them, so Sophia joined him.

Brunel spent 88 days in prison. He started writing to the Russian leader, Alexander I of Russia. He thought about moving his family to Russia to work for the Tsar. When important people in Britain, like the Duke of Wellington, heard this, they worried. They didn't want Britain to lose such a brilliant engineer. The government then gave £5,000 to pay off Brunel's debts. This was on the condition that he wouldn't go to Russia. So, Brunel was released from prison in August.

Building the Thames Tunnel

In 1805, a company tried to build a tunnel under the River Thames in London. They hired Richard Trevithick, another famous engineer. But the tunnel hit quicksand, and conditions became very dangerous. The project was stopped after about 1,000 feet. Experts believed such a tunnel was impossible.

Brunel had already designed a tunnel for Russia, but it was never built. In 1818, he patented a new invention: the tunnelling shield. This was a strong, reinforced iron shield. Miners would work inside separate sections of the shield, digging at the tunnel face. As they dug, large jacks would push the shield forward. Then, workers would line the tunnel walls with bricks.

It's said that Brunel got the idea for his shield from a tiny sea creature called a shipworm. This worm has a hard shell on its head that protects it as it bores through wood. Brunel's invention became the basis for future tunneling shields. These were used to build the London Underground and many other tunnels around the world.

Brunel was sure his shield could build a tunnel under the Thames. He wrote to many important people. Finally, in February 1824, a meeting was held, and money was raised for the project. In June 1824, the Thames Tunnel Company was officially formed. The tunnel was planned for horse-drawn carts.

Work began in February 1825. First, they dug a large vertical shaft, 50 feet wide, on the Rotherhithe side of the river. They did this by building a circular brick tower on a metal ring. As the tower grew, its weight pushed the ring into the ground. Workers dug out the earth from the center. This shaft was finished in November 1825. Then, the huge tunneling shield, made by Henry Maudslay's company, was put together at the bottom. Maudslay also provided the steam-powered pumps for the project.

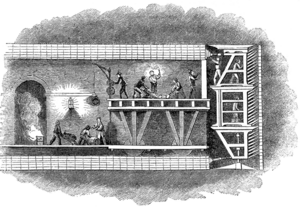

The shield was rectangular and had twelve frames side-by-side. Each frame could move forward on its own. Each frame had three small sections, one above the other. One miner could dig in each section. So, 36 miners could work at once! When enough earth was removed, the shield was pushed forward by big jacks. As the shield moved, bricklayers followed, lining the walls. The tunnel needed over 7.5 million bricks!

Challenges During Construction

Brunel's son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who was 18, helped him with the work. Marc Brunel had planned the tunnel to be only about fourteen feet below the riverbed at its lowest point. This caused problems later. Another challenge was William Smith, the company chairman. He thought the tunneling shield was too expensive and wanted to build the tunnel using older, cheaper methods. He often tried to get Brunel removed as Chief Engineer. But the shield quickly proved how valuable it was.

During the tunneling, both Brunel and his assistant got sick. For a while, Isambard had to manage all the work by himself. The tunnel flooded several times because it was so close to the riverbed. In May 1827, a huge hole appeared on the riverbed, and they had to plug it. The company ran out of money, and in August 1828, the tunnel was sealed up. Brunel resigned, frustrated by the chairman's constant opposition. He then worked on other projects, even helping his son Isambard with the design of the Clifton Suspension Bridge.

In March 1832, William Smith was removed as chairman. In 1834, the government agreed to loan the company £246,000. The old 80-ton tunneling shield was replaced with a new, improved 140-ton shield. This new shield had 9,000 parts that had to be put together underground. Tunnelling started again, but there were still floods. The pumps sometimes couldn't keep up. Miners got sick from the polluted water. As the tunnel neared the Wapping side, they started digging another vertical shaft, like the first one. This took thirteen months to complete, finishing in 1841.

On March 24, 1841, the young Queen Victoria made Brunel a knight. This was suggested by Prince Albert, who was very interested in the tunnel's progress. The tunnel opened on the Wapping side on August 1, 1842. On November 7, 1842, Brunel had a stroke, which paralyzed his right side for a time. The Thames Tunnel officially opened on March 25, 1843. Despite his poor health, Brunel attended the opening ceremony. Within 15 weeks, one million people visited the tunnel! Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited on July 26, 1843. Although it was meant for horse-drawn traffic, the tunnel remained only for people walking.

The Tunnel Today

In 1865, the East London Railway Company bought the Thames Tunnel for £200,000. Four years later, the first trains passed through it. The tunnel became part of the London Underground system. It is still used today as part of the East London Line of London Overground.

The old engine house in Rotherhithe was taken over by a charity in 1975. In 2006, it became the Brunel Museum, where you can learn more about this amazing engineer.

Later Years

After finishing the Thames Tunnel, his greatest achievement, Brunel's health was poor. He didn't take on many new big projects. But he did help his son, Isambard, with some of his designs. He was very proud of his son's work. He was there when the SS Great Britain, a huge ship designed by Isambard, was launched in Bristol in 1843.

In 1845, Brunel had another, more serious stroke. This left his right side almost completely paralyzed. On December 12, 1849, Marc Brunel died at the age of 80. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in London. His wife, Sophia, was later buried in the same spot. Their son, Isambard, was buried there just 10 years later.

Images for kids