Thames Tunnel facts for kids

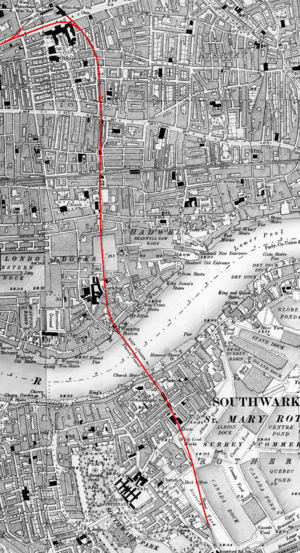

The Thames Tunnel is a famous tunnel located under the River Thames in London, England. It connects the areas of Rotherhithe and Wapping. This amazing structure is about 1,300 feet (396 meters) long, 35 feet (11 meters) wide, and 20 feet (6 meters) high. It runs about 75 feet (23 meters) below the river's surface when the tide is high.

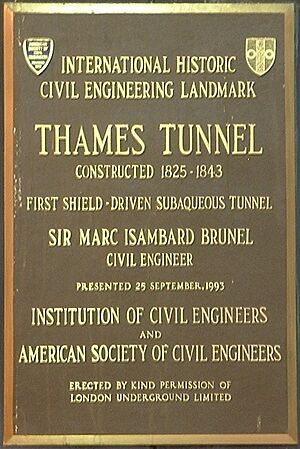

It was the first tunnel ever built successfully under a river that ships could sail on. Two brilliant engineers, Marc Brunel and his son, Isambard, built it between 1825 and 1843. They used a special invention called the tunnelling shield, which Marc Brunel and Thomas Cochrane created.

The tunnel was first meant for horse-drawn carriages, but it mostly became a popular walkway for people and a big tourist attraction. Later, in 1869, it was changed into a railway tunnel for the East London line. Today, it's part of the London Overground railway network, owned by Transport for London.

Contents

Building the Thames Tunnel

Early Attempts and New Ideas

In the early 1800s, London needed a new way to connect the north and south sides of the River Thames. This was important because the city's docks were growing on both sides. An engineer named Ralph Dodd tried to build a tunnel in 1799 but didn't succeed.

Later, between 1805 and 1809, a group of miners from Cornwall tried to dig a tunnel between Rotherhithe and Wapping. They were used to digging in hard rock and struggled with the soft clay and quicksand under the Thames. Their project, called the Thames Archway, failed after their small pilot tunnel flooded twice. This made many engineers believe that building an underground tunnel there was impossible.

However, a French-British engineer named Marc Brunel didn't give up. He had an idea for a new way to tunnel. In 1818, he got a patent for his amazing invention: the tunnelling shield.

Starting the Project

In 1823, Brunel proposed a plan to build a tunnel under the Thames using his new shield. He found investors, including the Duke of Wellington, and the Thames Tunnel Company was formed in 1824. Work began in February 1825.

The first step was to dig a large shaft on the south bank at Rotherhithe. This shaft was 50 feet (15 meters) wide. Workers dug the soil by hand from under a heavy iron ring, which slowly sank into the ground like a giant cookie cutter.

At one point, the shaft got stuck. Workers had to add 50,000 bricks to make it heavy enough to sink again. They learned that the shaft's sides should be slightly wider at the bottom to prevent it from getting stuck. By November 1825, the Rotherhithe shaft was ready, and the actual tunnel digging could begin.

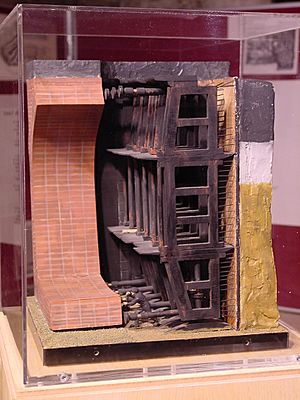

Digging with the Tunnelling Shield

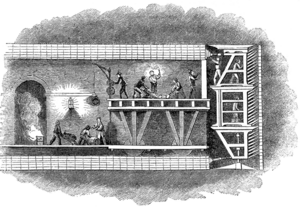

The tunnelling shield was key to building the Thames Tunnel. It was made of twelve heavy frames, each weighing over 7 tons. The shield supported the ground in front and around it, which helped prevent collapses.

However, conditions were very tough. Dirty, sewage-filled water from the river above often leaked into the tunnel. This water contained methane gas, which sometimes caught fire from the miners' oil lamps. Many workers, including Marc Brunel himself, became sick. In April 1826, Marc's 20-year-old son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, took over as the main engineer.

Work was slow, only progressing about 8 to 15 feet (2.4 to 4.6 meters) a week. To help earn money, the company allowed visitors to see the shield working. They charged a shilling, and 600 to 800 people visited every day.

Floods and Challenges

Digging the tunnel was very dangerous. On May 18, 1827, the tunnel suddenly flooded after 549 feet (167 meters) had been dug. Isambard Kingdom Brunel used a special diving bell from a boat to repair the hole in the riverbed, throwing bags of clay into the breach. After the repairs and draining the tunnel, he even held a banquet inside it!

The tunnel flooded again on January 12, 1828, and six men died. Isambard himself was very lucky to survive. He was pulled out unconscious and sent away to recover.

Finishing the Tunnel

In December 1834, Marc Brunel managed to raise more money, including a large loan from the government, to continue building. The old, rusty shield was taken apart, and a new, stronger one was put in place. Digging started again in March 1836.

The work faced more floods, fires, and leaks of dangerous gases like methane. Finally, the rest of the tunnel was completed in November 1841, after another five and a half years. The many delays and floods made the tunnel a joke in London. People even wrote poems about it, like this one:

Good Monsieur Brunel

Let misanthropy tell

That your work, half complete, is begun ill;

Heed them not, bore away

Through gravel and clay,

Nor doubt the success of your Tunnel.

That very mishap,

When the Thames forced a gap,

And made it fit haunt for an otter,

Has proved that your scheme

Is no catchpenny dream;—

They can't say "'twill never hold water".

The Thames Tunnel was fitted with lights, walkways, and spiral staircases between 1841 and 1842. An engine house was also built on the Rotherhithe side to pump water out of the tunnel. The tunnel finally opened to the public on March 25, 1843.

The Tunnel as a Pedestrian Walkway

Even though the Thames Tunnel was a huge engineering success, it didn't make much money. It cost a lot more than expected to build and fit out. Plans to make it suitable for carriages failed because of the high cost, so it was only used by people walking.

However, it became a very popular tourist attraction, drawing about two million visitors a year. Each person paid a penny to walk through it. People even wrote popular songs about the tunnel! An American traveler named William Allen Drew said that "No one goes to London without visiting the Tunnel" and called it the "eighth wonder of the world."

When he visited in 1851, he described it as more like an underground market than a simple pathway. He saw shops selling papers, books, and sweets in the entrance rotunda. As you went down the spiral stairs, the walls were decorated with paintings and statues. At the bottom, there was another round room with more shops and entertainers.

The tunnel itself had two arched pathways, each 14 feet (4.3 meters) wide. The wall between them had many smaller arches, which were turned into fancy shops. These shops had polished marble counters and mirrors, selling all sorts of souvenirs. Drew noted that it was "impossible to pass through without purchasing some curiosity."

Another American writer, Nathaniel Hawthorne, visited a few years later in 1855. He described the tunnel as a long, dark corridor lit by gas jets. He saw people who seemed to live there, running the little shops in alcoves along the tunnel. He felt that, for its original purpose, the tunnel was "an entire failure."

Becoming a Railway Tunnel

In September 1865, the tunnel was bought for £800,000 by the East London Railway Company. This company wanted to use the tunnel to connect different railway lines, moving both goods and passengers. The tunnel's high ceiling, originally designed for horse-drawn carriages, was perfect for trains.

The engineer for the railway line was Sir John Hawkshaw. The first train went through the tunnel on December 7, 1869. In 1884, the tunnel's old construction shaft on the north side was turned into Wapping station.

The East London Railway later became part of the London Underground. The Thames Tunnel was the oldest part of the Tube's underground system. It was even used for moving goods until 1962.

In 1995, the East London Line closed for a while for construction and repairs. There was a debate about how to repair the tunnel. London Underground wanted to seal it with concrete, which would change its original look. But people who wanted to preserve its history fought to keep its appearance. They won, and the tunnel was given a special "Grade II* listing" to protect it.

After an agreement to preserve most of its original look, the repair work went ahead. The line reopened in 1998. The tunnel closed again in 2007 for more upgrades. When it reopened on April 27, 2010, it became part of the new London Overground network, carrying mainline trains once more.

The Tunnel's Impact

The building of the Thames Tunnel proved that it was possible to construct tunnels under water. This success inspired many other underwater tunnels to be built in the UK, like the Tower Subway in London, the Severn Tunnel, and the Mersey Railway Tunnel. Brunel's tunnelling shield design was also improved over time by engineers like James Henry Greathead.

In 1991, the Thames Tunnel was recognized as an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by important engineering groups. In 1995, it was given a Grade II* listing because of its important architectural design.

Visiting the Tunnel

You can visit Brunel's original engine house in Rotherhithe, which is now the Brunel Museum. This museum tells the story of the tunnel and the Brunel family.

In the 1860s, when trains started using the tunnel, the entrance shaft at Rotherhithe was used for air circulation. The staircase was removed to prevent fires. In 2011, a concrete platform was built near the bottom of the shaft, above the train tracks. This smoky, historic space is now part of the museum and is sometimes used for concerts or events. There's also a garden on top of the shaft. In 2016, the original entrance hall opened as an exhibition space, and a new staircase allowed visitors to go down into the shaft for the first time in over 150 years.

See also

- Crossings of the River Thames

- Tunnels underneath the River Thames

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |