SS Great Britain facts for kids

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | Great Britain |

| Owner | Great Western Steamship Company |

| Port of registry | Bristol |

| Builder | William Patterson |

| Cost |

|

| Laid down | July 1839 |

| Launched | 19 July 1843 |

| Completed | 1845 |

| Maiden voyage | 26 July 1845 |

| In service | 1845–1886 |

| Homeport | Bristol, England 51°26′57″N 2°36′30″W / 51.4492°N 2.6084°W |

| Status | Museum ship |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Passenger steamship |

| Displacement | 3,674 tons load draught |

| Tons burthen | 3,443 bm |

| Length | 322 ft (98 m) |

| Beam | 50 ft 6 in (15.39 m) |

| Draught | 16 ft (4.88 m) |

| Depth of hold | 32.5 ft (9.9 m) |

| Installed power | 2 × twin 88-inch (220 cm) cylinder, bore, 6 ft (1.83 m) stroke, 500 hp (370 kW), 18 rpm inclined direct-acting steam engines |

| Propulsion | Single screw propeller |

| Sail plan |

|

| Speed | 10 to 11 knots (19 to 20 km/h; 12 to 13 mph) |

| Capacity |

|

| Complement | 130 officers and crew (as completed) |

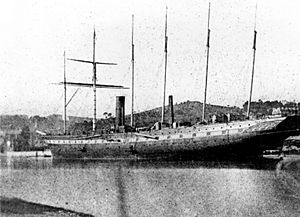

The SS Great Britain is a famous museum ship that was once a very advanced passenger steamship. From 1845 to 1853, she was the largest passenger ship in the world. Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859) designed her for the Great Western Steamship Company. Her job was to carry people across the Atlantic Ocean between Bristol, England, and New York City.

What made the Great Britain special was that she was the first large ocean-going ship to combine two new ideas: an iron body (hull) and a screw propeller. This made her one of the most high-tech ships of her time. In 1845, she became the first iron steamship to cross the Atlantic, completing the journey in 14 days.

The ship is 322 ft (98 m) long and weighs about 3,400 tons. She was powered by two large steam engines. She also had masts and sails for extra power. The ship had four decks, with space for 120 crew members and 360 passengers. Passengers enjoyed cabins, dining rooms, and walking areas.

When she was launched in 1843, the Great Britain was the biggest ship ever built. However, building her took six years (1839–1845) and cost a lot of money. This put her owners in financial trouble. In 1846, she ran aground in Dundrum Bay in County Down due to a navigation mistake. Her owners spent all their money trying to free her and went out of business.

In 1852, the ship was sold and repaired. From 1852, the Great Britain carried thousands of emigrants to Australia. In 1881, she was changed to rely only on sails. Three years later, she was moved to the Falkland Islands. There, she was used as a warehouse and a place to store coal until she was sunk on purpose (scuttled) in 1937.

In 1970, after being abandoned for 33 years, Sir Jack Hayward paid to bring the ship back to the United Kingdom. She was towed across the Atlantic to the same dry dock in Bristol where she was built 127 years earlier. Today, the Great Britain is a popular museum ship in Bristol Harbour. Around 150,000 to 200,000 people visit her every year.

Contents

How the Ship Was Developed

After their first successful ship, the SS Great Western in 1838, the Great Western Steamship Company started planning a new ship. It was first called City of New York. The same team of engineers who worked on the Great Western came together again. This team included Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Thomas Guppy, Christopher Claxton, and William Patterson. Brunel, who was very famous by then, took charge of the ship's design. The ship was built in a special dry dock in Bristol, England.

Choosing an Iron Body

Two important events changed how the Great Britain was designed. In late 1838, a ship called Rainbow visited Bristol. It was the largest ship with an iron body (hull) at the time. Brunel sent his team to travel on the Rainbow to see how well iron hulls worked. They were very impressed. Brunel then decided to change his plans from a wooden ship to an iron one. He convinced the company to do this.

Building with iron had many benefits over traditional wood. Wood was getting more expensive, while iron was becoming cheaper. Iron hulls did not rot or get eaten by worms. They were also lighter and took up less space. The biggest advantage was that iron hulls were much stronger. Wooden ships could only be about 300 ft (91 m) long before they would bend too much in waves. Iron hulls could be much longer without bending, allowing for much bigger ships. As Brunel and his team worked, the ship's design grew bigger and bolder. By the fifth design, the ship was planned to be 3,400 long tons (3,500 t), which was over 1,000 long tons (1,000 t) larger than any ship existing then.

Choosing a Screw Propeller

In early 1840, another important event happened. The revolutionary SS Archimedes arrived in Bristol. This was the first ship to be moved by a screw propeller. Brunel was very interested in this new technology. He had been trying to make his ship's paddlewheels better. The owner of Archimedes, Francis Pettit Smith, let Brunel borrow his ship for tests. For several months, they tested different propellers to find the best design. They found that a four-bladed propeller worked best.

Brunel was convinced that screw propellers were better. He wrote to the company directors to persuade them to make another big change. He wanted to stop building the paddlewheel engines (which were already half-finished) and build new engines for a propeller.

Brunel explained why screw propellers were better:

- They were lighter, which saved fuel.

- They could be placed lower in the ship, making it more stable in rough seas.

- They took up less space, so the ship could carry more cargo.

- Without big paddle boxes, the ship moved through water more easily. It could also steer better in tight spaces.

- A propeller stays fully underwater and works efficiently all the time. Paddlewheels change depth depending on the ship's weight and waves.

- Screw propulsion was cheaper to build.

Brunel's arguments worked, and in December 1840, the company agreed to use the new technology. This decision was expensive and delayed the ship's completion by nine months.

The Ship's Launch

The ship was launched, or floated out, on 19 July 1843. The weather was good, and many people came to Bristol to see the event. The city was decorated with flags and flowers. Everyone was excited because it was a public holiday.

Prince Albert arrived by train from London at 10 a.m. Brunel himself conducted the royal train. A police and military guard of honor greeted the Prince. After some speeches and a breakfast, the Prince boarded horse-drawn carriages.

At noon, the Prince arrived at the shipyard. The ship was already in the water, waiting for his inspection. He toured the ship and had refreshments in the elegant lounge. Later, there was a banquet with local important people.

After the banquet, the naming ceremony took place. Clarissa Miles, the wife of a company director, was chosen to christen the ship. She swung a champagne bottle towards the ship's front. But a steam tug, the Avon, started pulling the ship too early. The bottle missed and fell unbroken into the water. Quickly, a second bottle was found, and the Prince threw it against the iron hull.

Because the Avon started pulling too soon, the tow rope snapped. This caused a delay, and the Prince had to leave for the train station, missing the end of the event.

Another Long Delay

After the launch, the builders planned to tow the Great Britain to the Avon River for its final outfitting. However, the harbor officials had not made the necessary changes to the locks in time. To make things worse, the ship had been made wider than planned to fit the propeller engines. Also, the decision to install the engines before launch meant the ship sat deeper in the water.

This problem caused another expensive delay for the company. Brunel had to negotiate with the Bristol Dock Board for months. Finally, with help from the Board of Trade, the harbor agreed to change the locks. Work began in late 1844.

After being stuck in the harbor for over a year, the Great Britain was finally floated out in December 1844. But it caused more worry. After passing through the first set of lock gates, she got stuck in the second set, which led to the River Avon. Only the skill of Captain Claxton, the harbor master, saved her from serious damage. The next day, many workers, led by Brunel, removed parts of the lock gates during a slightly higher tide. This allowed the tugboat Samson to tow the ship safely into the Avon that night.

Ship's Design and Features

General Look

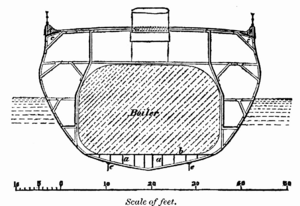

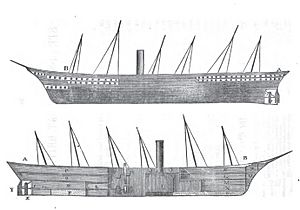

When finished in 1845, the Great Britain was a truly amazing ship. She was the first to have an iron body and a screw propeller. At 322 ft (98 m) long and weighing 3,400 tons, she was over 100 ft (30 m) longer and 1,000 tons bigger than any ship built before. She was 50 ft 6 in (15.39 m) wide and 32 ft 6 in (9.91 m) deep from her bottom to the main deck. She had four decks, a crew of 120, and could carry 360 passengers. She also had space for 1,200 tons of cargo and 1,200 tons of coal for fuel.

Like other steamships then, the Great Britain also had sails. She had one square-rigged mast and five schooner-rigged masts. This simple sail plan meant fewer crew members were needed. The masts were made of iron and could be lowered to reduce wind resistance. The ropes (rigging) were made of iron cable instead of traditional hemp, also to reduce wind resistance. Another new feature was light iron railings around the main deck instead of heavy walls. This saved weight and let water easily flow back into the sea in rough weather.

The ship's body and single smokestack (funnel) were painted black. A white stripe ran along the hull, with painted fake gunports. The hull was flat at the bottom and had no outside keel. It also had unusual bulges on the sides, a result of the last-minute decision to install wider propeller engines.

Brunel wanted to make sure the ship was incredibly strong to prevent bending (hogging) in such a large vessel. He designed the hull with many strong features. Ten long iron beams ran along the bottom. The iron ribs were 6 by 3 inches (15.2 cm × 7.6 cm) in size. The bottom plates were an inch thick, and many seams were double-riveted. For safety and strength, the ship had a double bottom and five watertight iron walls (bulkheads). In total, 1,500 tons of iron were used, including the engines.

Engines and Machinery

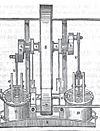

Two huge propeller engines, weighing 340 tons, were placed in the middle of the ship. They were based on a design by Brunel's father, Marc Isambard Brunel. These engines rose from the bottom of the ship through three decks. They had two large cylinders, each 88 in (220 cm) wide and with a 6-foot (1.8 m) stroke. They could produce 1000 horsepower at 18 rotations per minute. Steam came from three large "square" saltwater boilers, each 34-foot (10 m) long, 22-foot (6.7 m) high, and 10-foot (3.0 m) wide, with eight furnaces.

Brunel had no guide for the gearing system. The gears on the Archimedes were very noisy, which wouldn't work for a passenger ship. Brunel's solution was a chain drive. He put an 18-foot (5.5 m) wide gearwheel on the crankshaft between the two engines. This gearwheel, using four huge "silent" chains, turned a smaller gear near the bottom of the ship, which then turned the propeller shaft. This was the first time silent chain technology was used commercially, and these chains were likely the largest ever built.

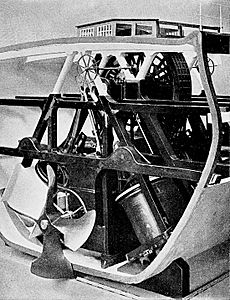

The Great Britain's main propeller shaft was the biggest single piece of machinery. It was 68 ft (21 m) long and 28 inches (71 cm) wide. It had a 10-inch-diameter (25 cm) hole through it to reduce weight and allow cold water to be pumped through to keep it cool. The total length of all three shafts was 130 ft (40 m), weighing 38 tons. The gears made the propeller spin three times faster than the engines, so at 18 rpm for the engines, the propeller spun at 54 rpm. The first propeller was Brunel's own six-bladed design, 16 ft (4.9 m) wide.

Inside the Ship

The ship had three main decks. The top two were for passengers, and the bottom one was for cargo. The passenger decks were split into front and back sections, separated by the engines and boilers in the middle.

At the back of the ship, the upper passenger deck had the main saloon (a large common room). It was 110 ft (34 m) long and 48 ft (15 m) wide. Along each side of the saloon were hallways leading to 22 passenger cabins, making 44 cabins in total for this area. Near the engine room, there were two private sitting rooms for ladies. These could be reached from 12 nearby cabins reserved for women. The saloon was painted in soft colors, had fixed oak chairs, and 12 decorated pillars.

Below the main saloon was the dining saloon. It was 98 ft 6 in (30.02 m) long and 30 ft (9.1 m) wide. It had dining tables and chairs for up to 360 people at once. On each side, seven hallways led to four cabins each, making 56 cabins in total. This dining saloon was the most impressive passenger area. It had 24 white and gold columns and eight decorated pillars with painted flowers and birds. The doorways were carved and gilded, with medallion heads above them. Mirrors made the room look bigger, and the walls were painted a light lemon color with blue and gold accents.

The two front saloons were similar to the back ones. The upper "promenade" saloon had 36 cabins per side, and the lower one had 30, totaling 132 cabins. Further forward were the crew quarters, separate from the passenger areas. The passenger areas were simpler than expected for the time, likely because the company was running low on money. The total cost to build the ship was £117,000, which was £47,000 more than the original plan.

Ship's History

Crossing the Atlantic

On 26 July 1845, seven years after the company decided to build a second ship, the Great Britain began her first journey. She sailed from Liverpool to New York with 45 passengers, led by Captain James Hosken. The trip took 14 days and 21 hours, which was not as fast as the record at the time. The return trip took 13 and a half days.

Brunel had replaced Smith's proven four-bladed propeller with his own six-bladed design. He then tried to make the ship faster by adding two inches of iron to each propeller blade. On her next trip to New York, carrying 104 passengers, the ship hit bad weather. She lost a mast and three propeller blades. On 13 October, she ran aground on the Massachusetts Shoals. She was freed and continued her journey after getting coal from another ship. After repairs in New York, she sailed back to Liverpool with only 28 passengers, losing four more propeller blades during the crossing. By this time, another problem was clear: the ship rolled a lot, especially in calm weather, which made passengers uncomfortable.

The company's owners provided more money to fix these issues. The six-bladed propeller was replaced with the original four-bladed, cast iron design. The third mast was removed, and the iron rigging was replaced with traditional ropes. To reduce the rolling, two 110-foot-long (34 m) bilge keels were added to each side. These repairs delayed her return to service until the next year.

In 1846, her second year of service, the Great Britain successfully completed two round trips to New York at a good speed.

She left Liverpool on 6 July 1846, for her sixth journey overall, and second that year, across the Atlantic. She arrived in New York on 21 July after 16 days. She carried only first-class passengers. Captain Hosken had 125 crew and 102 passengers. One passenger was Philip Borbeck, a printer returning home to Philadelphia from Germany. When Borbeck died in 1897, he left a large fortune.

The ship was then taken out of service for repairs to a worn-out chain drum. On her third trip of the season to New York, the captain made navigation mistakes. On 22 September, she ran hard aground in Dundrum Bay on the northeast coast of Ireland. There was no official investigation, but it is now thought that the captain did not have updated maps. He mistook a new lighthouse for another one.

She remained stuck for almost a year. Brunel and James Bremner organized temporary ways to protect her. On 25 August 1847, she was finally freed, but it cost £34,000. This expense used up all the company's remaining money. After sitting in Liverpool for some time, she was sold for only £25,000 to Gibbs, Bright & Co., who used to be agents for the Great Western Steamship Company.

Repairs and Back to Service

The new owners decided to completely refit the ship. The bottom (keel), which was badly damaged, was fully replaced for 150 feet (46 m) of its length. The owners also took the chance to make the hull even stronger. The old support beams were replaced, and 10 new ones were added along the entire keel. The front (bow) and back (stern) were also strengthened with heavy iron frames.

Because propeller engine technology had improved quickly, the original engines were removed. They were replaced with smaller, lighter, and more modern engines built by John Penn & Sons. These new engines had 82.5-inch (210 cm) cylinders and a 6-foot (180 cm) stroke. They were also better supported by iron and wood beams, which helped reduce engine vibration.

The complicated chain-drive gearing was replaced with a simpler and more reliable cog-wheel system. The gears still made the propeller shaft turn three times faster than the engines. The three large boilers were replaced with six smaller ones, which operated at twice the pressure. With a new 300-foot (91 m) cabin on the main deck, the smaller boilers allowed the cargo space to almost double, from 1,200 to 2,200 tons.

The four-bladed propeller was replaced by a slightly smaller three-bladed one. The bilge keels, added earlier to reduce rolling, were replaced by a heavy external oak keel for the same reason. The five-masted sail plan was changed to four masts, two of which were square-rigged. After these repairs, the Great Britain returned to service on the New York route. After only one more round trip, she was sold again to Antony Gibbs & Sons, who planned to use her for trips between England and Australia.

Trips to Australia

Antony Gibbs & Sons might have only planned to use the Great Britain for a short time. This was because many people wanted to travel to the Australian goldfields after gold was found in Victoria in 1851. However, the ship ended up working on this route for a long time. For her new role, she was refitted a third time. Her passenger capacity increased from 360 to 730. Her sail plan was changed to a traditional three-masted, square-rigged design. She was also fitted with a propeller that could be removed and pulled onto the deck by chains. This reduced drag when the ship was only using sails.

In 1852, the Great Britain made her first trip to Melbourne, Australia, carrying 630 emigrants. She caused a lot of excitement there, with 4,000 people paying to see her. She sailed on the England–Australia route for almost 30 years. She only stopped twice for short periods to carry soldiers during the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny. Over time, she became known as the most reliable ship for emigrants to Australia. She even carried the first English cricket team to tour Australia in 1861.

Alexander Reid wrote about a typical journey in 1862. The ship, with 143 crew, left Liverpool on 21 October 1861. She carried 544 passengers (including the cricket team), a cow, 36 sheep, 140 pigs, 96 goats, and 1,114 chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys. The trip to Melbourne (her ninth) took 64 days. The captain was John Gray, who had been in charge since before the Crimean War.

On 8 December 1863, it was reported that she had been wrecked on Santiago, Cape Verde Islands. This happened while she was traveling from London to Nelson, New Zealand. Everyone on board was rescued.

Her passengers and crew saw a total solar eclipse in 1865 while sailing near Brazil. They could even see stars in the daytime.

On 8 October 1868, The Argus newspaper reported that the Great Britain was leaving Melbourne for Liverpool. She had fewer passengers than usual but a full cargo, including gold worth about £250,000. Captain Gray mysteriously disappeared overnight during a return trip from Melbourne on 25/26 November 1872. On 22 December, she rescued the crew of another British ship, the Druid, which had been abandoned in the Atlantic Ocean. On 19 November 1874, she crashed into the British ship Mysore, losing an anchor and damaging her hull.

Later Years

In 1882, the Great Britain was changed into a sailing ship to carry large amounts of coal. She made her last journey in 1886. She loaded coal in Penarth Dock in Wales and left for San Francisco on 8 February. A fire broke out on board during the trip. When she arrived at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands, she was too damaged to be repaired cheaply. She was sold to the Falkland Islands Company and used as a floating storage hulk (a coal bunker) until 1937. Then, she was towed to Sparrow Cove, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from Port Stanley, sunk on purpose, and left there. As a coal bunker, she supplied coal to the fleet that defeated Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee's fleet in the Battle of the Falkland Islands during the First World War. In the Second World War, some of her iron was used to repair HMS Exeter, a Royal Navy ship damaged in the Battle of the River Plate.

Famous People on Board

The Great Britain carried over 33,000 people during her time at sea. Some notable passengers and crew included:

- Gustavus Vaughan Brooke: An Irish actor who traveled between Melbourne and Liverpool in 1861.

- Fanny Duberly: An author who wrote about the Crimean War; she traveled between Cork and Mumbai in 1857.

- Colonel Sir George Everest: A British surveyor and geographer, for whom Mount Everest is named; he traveled between Liverpool and New York in 1845.

- John Gray: The Great Britain's longest-serving captain, who mysteriously disappeared at sea.

- James Hosken: The first captain of the Great Britain.

- Avonia Jones: An American actress who traveled with Gustavus Vaughan Brooke in 1861.

- Anthony Trollope: A famous English novelist; he traveled between Liverpool and Melbourne in 1871 and wrote a novel during the voyage.

- Francis Pettit Smith: One of the inventors of the screw propeller; he traveled between Liverpool and New York in 1852.

Bringing the Ship Back to Life

The effort to save the ship was made possible by large donations from people like Sir Jack Hayward and Sir Paul Getty. The 'SS Great Britain Project' organized the salvage. Experts confirmed the ship could be refloated. A special floating platform, Mulus III, was rented in February 1970. A German tugboat, Varius II, arrived in Port Stanley on 25 March. By 13 April, the ship was successfully placed on the platform. The next day, the tug, platform, and Great Britain sailed to Port Stanley to prepare for the trip across the Atlantic.

The journey, called "Voyage 47," began on 24 April. They stopped in Montevideo from 2 to 6 May for inspection. Then they crossed the Atlantic, arriving at Barry Docks in Wales on 22 June. (The name "Voyage 47" was chosen because it was on her 47th voyage, in 1886, that she sought shelter in the Falklands.) Bristol tugboats then took over and towed her, still on her platform, to Avonmouth Docks.

The ship was then taken off the platform to prepare for her return to Bristol, now truly floating again. On Sunday, 5 July, with many media watching, the ship was towed up the River Avon to Bristol. A memorable moment for the crowds was her passage under the Clifton Suspension Bridge, another famous design by Brunel. She waited for two weeks in the Cumberland Basin for a high enough tide to pass through the locks. Finally, she returned to her birthplace, the dry dock in the Great Western Dockyard.

The recovery and journey from the Falklands to Bristol were shown in a 1970 BBC TV show called The Great Iron Ship.

At first, the plan was to restore her to how she looked in 1843. However, the goal changed to preserving all the original parts that survived until 1970. In 1984, the SS Great Britain was recognized as a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark.

By 1998, a detailed study found that the hull was still rusting in the humid air of the dock. Experts estimated she had only 25 years left before she would rust away completely. Extensive conservation work began. This led to installing a glass plate across the dry dock at the ship's waterline. Two dehumidifiers keep the space below the ship at 20% humidity, dry enough to preserve the remaining materials. After this was finished, the ship was "re-launched" in July 2005, and visitors could access the dry dock again. The site now welcomes over 150,000 visitors each year.

Awards and Recognition

The engineers Fenton Holloway won an award for Heritage Buildings in 2006 for their work on the Great Britain. In May of that year, the ship won the prestigious Gulbenkian Prize for museums and galleries. Professor Robert Winston, who led the judges, said the Great Britain was outstanding. He praised its amazing conservation, engineering, social history, and how visually stunning it is. He also noted that it is easy to access and engaging for all ages.

The project also won The Crown Estate Conservation Award in 2007. It received the European Museum of the Year Awards Micheletti Prize for 'Best Industrial or Technology Museum'. In 2008, the project's educational value was honored with the Sandford Award for Heritage Education.

Being Brunel Museum

Being Brunel is a museum dedicated to Isambard Kingdom Brunel. It was built next to his ship in the harbor and opened in 2018. The museum holds thousands of items related to Brunel, such as his school reports, diaries, and drawing tools. It cost £2 million and is located in buildings on the quayside, including Brunel's original drawing office. The museum includes a recreation of his dining room and has restored his drawing office to how it looked in 1850.

Ship's Measurements

- Length: 322 ft (98 m)

- Width (Beam): 50.5 ft (15.39 m)

- Height (main deck to keel): 32.5 ft (9.91 m)

- Weight when empty: 1,930 long tons (2,160 short tons; 1,960 tonnes)

- Displacement (weight of water pushed aside): 3,018 long tons (3,380 short tons; 3,066 tonnes)

Engine Details

- Power: 1,000 horsepower (750 kW)

- Weight: 340 long tons (380 short tons; 350 tonnes)

- Cylinders: 4 x inverted 'V' 88 inches (223.5 cm) bore

- Stroke: 72 inches (182.9 cm)

- Pressure: 5 psi (34 kPa)

- RPM (rotations per minute): Max. 20 rpm

- Main crankshaft: 17 feet (5.18 m) long and 28 inches (71.1 cm) wide

Propeller Details

- Diameter: 15.5 ft (4.72 m)

- Weight: 77 long hundredweight (3,900 kg)

- Speed: 55 rpm

Other Facts

- Fuel capacity: 1,100 long tons (1,232 short tons; 1,118 tonnes) of coal

- Water capacity: 200 long tons (224 short tons; 203 tonnes)

- Cargo capacity: 1,200 long tons (1,344 short tons; 1,219 tonnes)

- Cost to build: £117,295

See also

In Spanish: SS Great Britain para niños

In Spanish: SS Great Britain para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |