SS Archimedes facts for kids

The SS Archimedes

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | Archimedes |

| Namesake | Archimedes of Syracuse |

| Owner | Ship Propeller Company |

| Builder | Henry Wimshurst (London) |

| Cost | £10,500 |

| Launched | 18 October 1838 |

| Completed | 1839 |

| Maiden voyage | 2 May 1839 |

| In service | 2 May 1839 |

| Refit | As a sailing ship, date unknown |

| Fate | Reportedly ended career in Chile–Australia service, 1850s |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Steam powered schooner |

| Tons burthen | 237 |

| Length | 125 ft (38 m) |

| Beam | 22 ft (6.7 m) |

| Draught | 8–9 ft (2.4–2.7 m) |

| Depth of hold | 13 ft (4.0 m) |

| Installed power | 2 × 30 hp (22 kW), 25–30 rpm twin-cylinder Rennie vertical steam engines, with 37-inch cylinders and 3-foot stroke |

| Propulsion | 1 x full helix, single turn, single threaded iron propeller operating at 130–150 rpm, auxiliary sails |

| Sail plan | Three-masted, schooner-rigged |

| Speed | About 10 mph (16 km/h) (under steam) |

| Notes | World's first screw-propelled steamship |

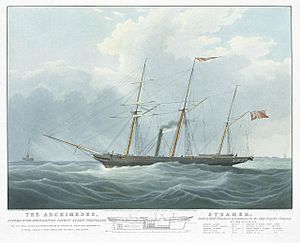

SS Archimedes was a steamship built in Britain in 1839. She was the world's first steamship to be successfully moved by a screw propeller. This means she used a spinning blade underwater to push herself forward.

Archimedes had a big impact on how ships were built. She helped the Royal Navy (Britain's navy) decide to use screw propellers. She also influenced the design of another famous ship, Isambard Kingdom Brunel's SS Great Britain. That ship was the largest in the world at the time and the first screw-propelled steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Contents

Early Ideas for Screw Propellers

People have known about the idea of moving water with a screw for a very long time. The Archimedes' screw, named after Archimedes of Syracuse (who lived in ancient Greece), is an old invention for lifting water.

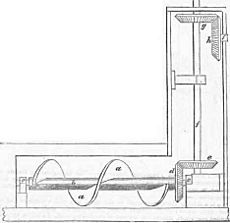

However, it wasn't until the 1700s, with the invention of the steam engine, that people had enough power to make a ship move with a screw. Many early attempts to build such a ship didn't work well.

In 1807, the first successful steam-powered ship, Robert Fulton's North River Steamboat, appeared. This ship used large paddlewheels on its sides to move. Because it worked so well, paddlewheels became the standard way to power steamships for a while. But some inventors kept trying to make screw propellers work. Between 1750 and the 1830s, many people got patents for marine propellers. However, most of these ideas were never tested, or they didn't work very well.

Inventors: Ericsson and Smith

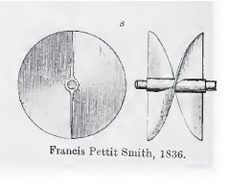

In 1835, two inventors in Britain, John Ericsson and Francis Pettit Smith, started working on screw propellers separately. Smith, a farmer who loved the idea of screw propulsion, was the first to get a patent for his propeller on May 31. Ericsson, a talented Swedish engineer, filed his patent six weeks later.

Smith quickly built a small model boat to test his idea. He showed it on a pond at his farm and later in London. Sir John Barrow, a high-ranking official from the Admiralty (the British Navy's leaders), saw it. With money from a banker named Wright, Smith then built a 30-foot (9.1 m) canal boat called Francis Smith. It had a wooden propeller and was shown on the Paddington Canal from November 1836 to September 1837.

By chance, the wooden propeller, which had two turns, broke during a trip in February 1837. To Smith's surprise, the broken propeller, now with only one turn, made the boat go twice as fast! It went from about four miles per hour (6.4 km/h) to eight miles per hour (13 km/h). Smith then got a new patent for this improved, single-turn design.

Meanwhile, Ericsson was doing his own tests. In 1837, he built a 45-foot (14 m) screw-propelled steamboat, Francis B. Ogden. He showed his boat on the River Thames to important members of the British Admiralty, including Sir William Symonds. Even though the boat reached ten miles per hour (16 km/h), which was as fast as paddle steamers, the Admiralty wasn't impressed. They thought screw propellers wouldn't work well in the ocean. Symonds also believed screw ships couldn't be steered properly.

After this rejection, Ericsson built a second, larger screw-propelled boat, Robert F. Stockton. He sailed it to the United States in 1839. There, he became famous for designing the U.S. Navy's first screw-propelled warship, USS Princeton.

Smith knew the Navy didn't think screw propellers were good for ocean travel. So, he decided to prove them wrong. In September 1837, he took his small boat (now with an iron propeller of one turn) out to sea. He sailed from Blackwall, London to Hythe, Kent, stopping at Ramsgate, Dover, and Folkestone. On the way back, Royal Navy officers saw Smith's boat moving well in stormy seas.

The Admiralty became interested again. Smith was encouraged to build a full-sized ship to show how well the technology worked. He found investors, including the banker Wright and the engineering company J. and G. Rennie. They formed a new company called the Ship Propeller Company. Their new ship was first called Propeller, but they eventually named it Archimedes, after the ancient Greek inventor.

Building the Archimedes

Archimedes was built in London in 1838 by Henry Wimshurst. Smith said the ship was made of English oak. However, later records show that parts of the keel (the bottom structure of the ship) were made of Baltic fir wood. The ship was 125 feet (38 m) long and 22+1⁄2 feet (6.9 m) wide. It weighed 237 tons.

Archimedes was built like a schooner, a type of sailing ship. It had classic hull lines and a slim, leaning funnel (smokestack) and masts. People at the time thought she was a very beautiful ship.

Engines and Propeller

Smith had some trouble finding the right engines for the ship. Screw propulsion was a new challenge. Finally, the well-known engineering company J. and G. Rennie agreed to build the engines. The Rennies also decided to invest money in the ship and its new technology.

The two engines built by the Rennies each had two large cylinders. They produced about 80 nominal horsepower (a way to measure engine power). The engines turned at 26 rpm (revolutions per minute). Through gears, they made the propeller shaft spin much faster, at about 140 rpm. The boilers (which made steam for the engines) operated at a pressure of 6 psi. The engines were put into the ship in early 1839, after the ship was launched in October 1838.

The gears caused some problems. Smith used large spur-wheels and pinions (smaller gears) to connect the engines to the propeller. The largest gear was made of hornbeam wood, which was traditionally used for gears in windmills. This gearing system was very noisy. The back of the ship also vibrated a lot when it was running. Smith planned to use spiral gears to make it quieter, but it's not clear if this was ever done.

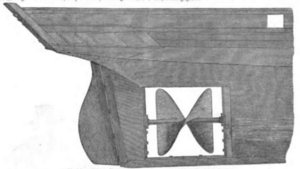

The propeller itself was made of sheet iron. It was 5 feet 9 inches (1.75 m) wide and about 5 feet (1.5 m) long. It was a single, full 360-degree screw, just like Smith's updated patent. After the ship started service, the propeller was changed several times. The most important change was making it a double-threaded, half-turn propeller with two separate blades. This new propeller greatly reduced the vibration at the back of the ship.

A unique feature of the propeller was that it could be pulled up out of the water. This reduced drag when the ship was using its sails. It took about 15 minutes to pull the propeller up.

Archimedes at Sea

Archimedes made her first trip from London to Sheerness on May 2, 1839. On May 15, she started her first sea voyage from Gravesend to Portsmouth. She finished this trip at an unexpectedly fast speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). In Portsmouth, Archimedes was tested against one of the fastest ships the Admiralty had, HMRC Vulcan. Senior Navy officials watched and were impressed by Archimedes' performance.

Repairs and Propeller Changes

After this first test, Archimedes started a trip back to London. But during the journey, the ship's boiler exploded. It didn't have a gauge or a safety valve. The explosion killed the second engineer and badly burned several other people. The ship then had to be repaired for five months at Wimshurst's shipyard.

After repairs, Smith was invited by the Dutch government to bring the ship to the Netherlands for a demonstration. He agreed. However, on the way to the Texel island, Archimedes broke her crankshaft (a part of the engine). She had to return to England for more repairs. During this repair, the original single-turn propeller was replaced with a double-threaded, half-turn propeller with two separate blades. This new propeller made the ship vibrate much less at the stern.

Dover Trials

After these repairs, the British Admiralty arranged new tests for Archimedes at Dover. Captain Edward Chappell was put in charge of these tests. From April to May 1840, Archimedes was tested against the Navy's fastest mail ships that went between Dover and Calais. These were paddlewheelers named Ariel, Beaver, Swallow, and Widgeon.

The most important tests were against Widgeon. Widgeon was the fastest mail ship and was similar in size and power to Archimedes. Widgeon was a little faster than Archimedes in calm seas. But Captain Chappell concluded that, because Archimedes had less horsepower for its weight, the screw propeller was "equal, if not superior, to that of the ordinary paddle-wheel."

This finding was very important for the Navy. Screw propulsion only needed to be about as good as paddlewheels. Paddlewheels had big problems for military use. They were exposed to enemy fire, and they took up space that could be used for cannons. Chappell's report later led the Navy to choose screw propulsion for its warships.

Sailing Around Britain and Other Trips

After the Dover trials, Captain Chappell took Archimedes on a trip around Britain in July 1840. This trip allowed more tests and let ship owners, engineers, and scientists see the new technology in ports across the country. Archimedes traveled 2,006-mile (3,228 km) at an average speed of over 7 miles per hour (11 km/h). In perfect conditions, she reached a top speed of 10.9 miles per hour (17.5 km/h).

After this long trip, Archimedes sailed from Plymouth to Oporto, Portugal in a record time of 68 and a half hours. The ship then made more trips to Antwerp, to Amsterdam through the North Holland Canal, and to other ports in Europe. Everywhere she went, people were very interested in the new way of moving ships.

Loan to Brunel

When Archimedes returned to England, Smith agreed to lend her for several months to the Great Western Steamship Company. This company was building the world's largest steamship, SS Great Britain. The main engineer for Great Western, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, used Archimedes to test many different propellers. He wanted to find the best design. He eventually chose a new four-bladed propeller designed by Smith.

Brunel's tests made him recommend that his company use screw propulsion for Great Britain. Here are some reasons Brunel gave for using a screw propeller:

- Screw propeller machinery was lighter, which saved fuel.

- It could be placed lower in the ship, making the ship more stable in rough seas.

- Propeller engines took up less room, so more cargo could be carried.

- Without bulky paddle-boxes, the ship would move through water more easily. It could also maneuver better in tight spaces.

- Paddlewheels constantly change how deep they are in the water, depending on the ship's cargo and waves. A propeller stays fully underwater and works at full power all the time.

- Screw propulsion machinery was cheaper.

Because of these reasons, Brunel convinced the Great Western Steamship Company in December 1840 to use screw propulsion for Great Britain. This made her the world's first screw-propelled ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean. However, Brunel later decided to use his own six-bladed "windmill" propeller instead of Smith's proven design. Brunel's design didn't work well and was quickly replaced with the original design.

Later Years of Archimedes

Smith and his investors had hoped to sell Archimedes to the Royal Navy. But when that didn't happen, the Ship Propeller Company sold the ship for regular commercial use. The company lost about £50,000 on the Archimedes project and later closed down.

The later history of Archimedes is not fully clear. The ship ran aground (got stuck on the bottom) at Beachy Head in 1840. In 1845, she disappeared from Lloyd's Register (a list of ships), but reappeared in 1847 after an overhaul (major repair). Her engines were removed at Sunderland at some point. After that, she continued to sail as a sailing ship.

In 1850, she was listed as belonging to the Elbe & Humber Steam Navigation Company, sailing between Hamburg and Hull. In 1852, her sails and rigging were replaced. But she disappeared from the Register again a year or two later. In early November 1852, there was a fire in her back hold while she was sailing from Hull to Hamburg. She arrived in Hamburg on November 9 with the back hold flooded. She reportedly finished her career in the 1850s, sailing between Chile and Australia. A schooner with the same name was wrecked on January 27, 1857, in the Tuamotus islands, while sailing between Valparaiso and Melbourne.

Archimedes's Lasting Impact

Even though other inventors like John Ericsson were also working on screw propellers, Archimedes greatly sped up how quickly this technology was accepted. The Dover trials in 1840 convinced the Royal Navy to build a 900-ton steam sloop-of-war (a type of warship) called HMS Rattler. This ship was tested from 1843 to 1845 against HMS Alecto, a sister ship (a ship of the same design) that used paddle propulsion. Because of these tests, the Navy chose the screw propeller as its preferred way to power ships. By 1855, 174 ships in the Royal Navy had screw propellers.

Some merchants also quickly started using screw propulsion. In 1840, Wimshurst built a second propeller-driven ship, the 300-ton Novelty. This was the first screw-propelled cargo ship and the first to make a commercial voyage. In 1841, a small passenger steamer with Smith's patented propeller, Princess Royal, was built. In 1842, several more screw-propelled ships were built in Britain. From this point on, the number of merchant ships with screw propellers grew very quickly. By the time the Cunard Line built the paddle steamer Persia for transatlantic service in 1856, paddlewheels were already becoming old-fashioned.

Even though Smith's Archimedes played a huge role in bringing screw propulsion to the world, Smith himself lost money on the project. He had to go back to farming. However, he was later recognized for his contribution. In 1855, he was one of five inventors who received £4,000 each from the House of Commons for inventing the marine propeller. In 1858, a group of supporters held a special dinner for him. He was given silver gifts worth £2,678. In 1860, Smith became the Curator of the Patent Office Museum in South Kensington. In 1871, he received a knighthood, which meant he became Sir Francis Pettit Smith.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |