Sunderland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sunderland |

|

|---|---|

| City | |

|

|

| Population | 168,277 (2021 Census) |

| Demonym | Mackem |

| OS grid reference | NZ395575 |

| • London | 240 miles (390 km) SSE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SUNDERLAND |

| Postcode district | SR1–SR6 |

| Dialling code | 0191 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Tyne and Wear |

| Ambulance | North East |

| EU Parliament | North East England |

| UK Parliament |

|

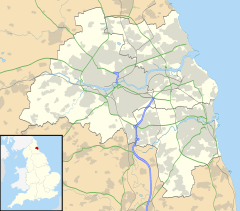

Sunderland is a port city in Tyne and Wear, England. It sits at the mouth of the River Wear by the North Sea. It is about 10 miles (16 km) south-east of Newcastle upon Tyne. In 2021, the city area had 168,277 people. This makes it the second largest city in North East England after Newcastle. Sunderland is the main city of the metropolitan borough of the same name.

Sunderland was once famous for shipbuilding. It was known as 'the largest shipbuilding town in the world'. At one point, it built a quarter of all the world's ships. Its shipyards on the River Wear date back to 1346.

The modern city grew from three old settlements. These were founded in the Anglo-Saxon era. They were Monkwearmouth (north of the Wear), and Sunderland and Bishopwearmouth (south of the Wear). Monkwearmouth has St Peter's Church. It was built in 674 and was part of Monkwearmouth–Jarrow Abbey. This abbey was a major learning center long ago. Sunderland started as a fishing village and then became a port. It got its town charter in 1179. The city traded in coal and salt. It also developed shipbuilding in the 1300s and glassmaking in the 1600s. After its old industries declined in the late 1900s, it became a center for making cars. In 1992, Sunderland became a city. It was historically part of County Durham but joined Tyne and Wear in 1974.

People from Sunderland are sometimes called Mackems. This name became popular in the 1970s. The term also refers to the local way of speaking, which is similar to other North East England accents.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Around 674, King Ecgfrith gave land to Benedict Biscop. This land was called a "sunder-land," meaning "separate land." In 685, The Venerable Bede moved to the new Jarrow monastery. He had started his monk life at Monkwearmouth. He wrote that he was "born in a separate land of this same monastery." This could mean the settlement of Sunderland. The name might also describe the area. It was almost cut off by creeks from the sea and the River Wear.

Sunderland's Story

Early Times and Medieval History

The first people in the Sunderland area were Stone Age hunters and gatherers. Tools from this time have been found near St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth. During the late Stone Age (around 4000-2000 BC), Hastings Hill was a special place for burials and rituals.

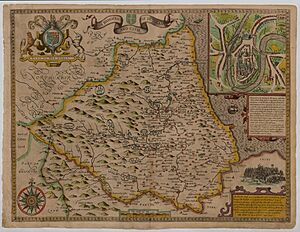

People believe the Brythonic-speaking Brigantes lived near the River Wear before the Romans. There's a local story about a Roman settlement on the south bank of the Wear. However, no digs have proven this. Roman items, like stone anchors, have been found in the River Wear at North Hylton. This suggests there might have been a Roman port there.

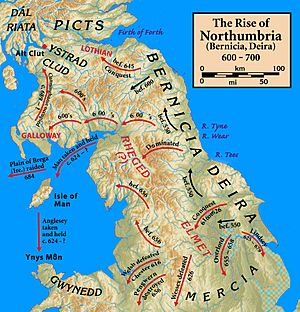

Records show settlements at the Wear's mouth around 674. An Anglo-Saxon nobleman, Benedict Biscop, got land from King Ecgfrith. He founded the Wearmouth–Jarrow (St Peter's) monastery on the north bank. This area became Monkwearmouth. Biscop's monastery was the first stone building in Northumbria. He brought French glassmakers, restarting glass making in Britain. In 686, Ceolfrid took over. Wearmouth–Jarrow became a huge learning center in Anglo-Saxon England. It had a library of about 300 books.

The Codex Amiatinus, a very important book, was made at the monastery. Bede, born at Wearmouth in 673, likely worked on it. This is one of England's oldest standing monasteries. While there, Bede wrote Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People) in 731. This earned him the title The father of English history.

In the late 700s, Vikings attacked the coast. By the mid-800s, the monastery was empty. In 930, Athelstan of England gave land on the south side of the river to the Bishop of Durham. This area became Bishopwearmouth. It included places like Ryhope, now part of Sunderland.

By 1100, Bishopwearmouth had a fishing village at the river's southern mouth. This village was called 'Soender-land'. It later became 'Sunderland'. In 1179, Hugh Pudsey, the Bishop of Durham, gave this settlement a charter. It was called the borough of Wearmouth. This charter gave its traders the same rights as those in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. But it still took time for Sunderland to grow as a port. Fishing was the main business. They caught herring in the 1200s and salmon in the 1300s and 1400s. From 1346, ships were built at Wearmouth. By 1396, a small amount of coal was being sent out.

Salt, Coal, and Ships

The port grew quickly because of the salt trade. Sunderland exported salt from the 1200s. By 1589, salt pans were set up at Bishopwearmouth Panns. This area is now called Pann's Bank. Large tubs of seawater were heated with coal. As the water dried up, salt was left behind. Coal was needed for the salt pans, so coal mining grew. Only poor-quality coal was used for salt. Better coal was traded through the port, which then grew even more.

Both salt and coal were exported through the 1600s. The coal trade grew a lot. In 1600, 2,000-3,000 tons of coal were exported. By 1680, this was 180,000 tons. It was hard for large coal ships to sail in the shallow Wear. So, coal from further inland was put onto keels (flat-bottomed boats). These boats took the coal downriver to the waiting ships. A group of workers called 'keelmen' operated the keels. In 1634, Bishop Thomas Morton gave a charter for a market and fair. Morton's charter said the area had been called Wearmouth. But it officially named the place Sunderland, as it was becoming more known by that name.

Before the English Civil War, the North of England supported the King. In 1644, the Roundheads (Parliamentarians) took over the North. They blocked the River Tyne, stopping Newcastle's coal trade. This allowed Sunderland's coal trade to boom for a short time.

In 1669, after the King returned, King Charles II allowed Edward Andrew to 'build a pier and lighthouse and clean the harbour of Sunderland'. Ships had to pay a duty to raise money for this. More shipbuilders were active on the River Wear in the late 1600s.

By the early 1700s, the Wear's banks were full of small shipyards. After 1717, the river was made deeper. Sunderland's shipbuilding grew a lot, along with its coal exports. Many warships and trading ships were built. By the mid-1700s, Sunderland was probably the top shipbuilding center in Britain. Ships built here were called 'Jamies'. By 1788, Sunderland was Britain's fourth largest port. It was the main coal exporter. Even more growth came from London's huge need for coal during the French Revolutionary Wars.

Until 1719, Sunderland was part of Bishopwearmouth parish. After Holy Trinity Church, Sunderland was finished in 1719, Sunderland became its own parish. Later, in 1769, St John's Church was built. By 1720, the port area was fully built up. Large houses faced the Town Moor and the sea. Workers' homes and factories were by the river. The three original settlements began to join together. This was due to the success of Sunderland's port, salt panning, and shipbuilding. At this time, Sunderland was known as 'Sunderland-near-the-Sea'.

Sunderland's third biggest export was glass. The town's first modern glass factories opened in the 1690s. The industry grew in the 1700s. Trading ships brought good sand (as ballast) from the Baltic Sea. This, with local limestone and coal, was key for glassmaking. Other industries by the river included lime burning and pottery making. The first pottery factory, Garrison Pottery, opened in 1750.

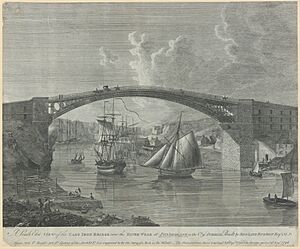

By 1770, Sunderland had spread west along its High Street to meet Bishopwearmouth. In 1796, Bishopwearmouth connected to Monkwearmouth. This happened when the Wearmouth Bridge was built. It was the world's second iron bridge. It was described as 'a triumph of new metal and engineering'. It spanned 236 feet (72 meters) in one go. It was twice as long as the first iron bridge but weighed less. It was the biggest single-span bridge in the world then. Sunderland was on a plateau above the river, so the bridge didn't stop tall ships.

During the War of Jenkins' Ear, two gun batteries were built (1742 and 1745). They were on the shoreline south of the South Pier. They defended the river from attack. One was washed away in 1780. The other was made bigger during the French Revolutionary Wars. It became known as the Black Cat Battery. In 1794, Sunderland Barracks were built behind the battery.

The world's first steam dredger was built in Sunderland in 1796-97. It started working on the river the next year. It was designed to dig up to 10 feet (3 meters) below the water. It worked until 1804. On land, many small businesses supported the growing port. In 1797, the world's first factory for machine-made rope was built in Sunderland. It used a steam-powered machine invented by a local schoolmaster. The building still stands in the Deptford area.

The World's Biggest Shipbuilding Port

Sunderland's shipbuilding grew through most of the 1800s. It became the town's main industry. By 1815, it was the top port for building wooden trading ships. 600 ships were built that year in 31 different yards. By 1840, the town had 76 shipyards. Between 1820 and 1850, the number of ships built on the Wear increased five times. From 1846 to 1854, almost a third of the UK's ships were built in Sunderland. In 1850, the Sunderland Herald newspaper said the town was the greatest shipbuilding port in the world.

The Durham & Sunderland Railway Co. built a railway line. It crossed the Town Moor and opened a passenger station in 1836. In 1847, George Hudson bought the line. Hudson, known as 'The Railway King', was a Member of Parliament for Sunderland. He also started the Sunderland Dock Company in 1846. This company got permission to build a dock between the South Pier and Hendon Bay.

More factories led to new homes. People moved from the old port to areas like Fawcett Estate and Mowbray Park. The area around Fawcett Street became the town's main center for shopping and city business.

Factories for marine engines started in the 1820s. They first made engines for paddle steamers. In 1845, a ship called Experiment was the first to be changed to steam screw propulsion. Demand for steam ships grew during the Crimean War. But sailing ships were still built. These included fast clippers like the City of Adelaide (1864) and Torrens (1875).

By the mid-1800s, glassmaking was at its peak in Sunderland. James Hartley & Co., started in 1836, became the country's largest glassworks. They invented a new way to make rolled plate glass. They produced much of the glass for the Crystal Palace in 1851. By this time, Hartley's made a third of all UK plate glass. Other factories made pressed glass. In the 1850s, there were 16 bottle factories on the Wear. They could make 60,000 to 70,000 bottles a day.

In 1848, George Hudson's railway built a station, Monkwearmouth Station, north of Wearmouth Bridge. South of the river, another station opened in Fawcett Street in 1853. Later, Thomas Elliot Harrison planned to take the railway across the river. The Wearmouth Railway Bridge opened in 1879. It was said to be the 'largest Hog-Back iron girder bridge in the world'.

In 1854, the Londonderry, Seaham & Sunderland Railway opened. It connected coal mines to docks at Hudson Dock South. It also offered passenger service from Sunderland to Seaham Harbour.

From 1886 to 1890, Sunderland Town Hall was built in Fawcett Street. By 1889, two million tons of coal passed through Hudson Dock each year. South of Hendon Dock, the Wear Fuel Works made pitch, oil, and other products from coal tar.

The 1900s saw Sunderland A.F.C. become famous. The football club started in 1879. Sunderland joined The Football League for the 1890–91 season.

The 1900s and Beyond

From 1900 to 1919, an electric tram system was built. Buses slowly replaced it in the 1940s, and it ended in 1954. In 1909, the Queen Alexandra Bridge was built. It connected Deptford and Southwick.

The First World War made shipbuilding increase. This made Sunderland a target for a 1916 Zeppelin raid. Monkwearmouth was hit on April 1, 1916, and 22 people died. Over 25,000 men from 151,000 people served in the war.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, shipbuilding greatly declined. Shipyards on the Wear went from 15 in 1921 to six in 1937. Some smaller yards closed in the 1920s. Others were shut down by National Shipbuilders Securities in the 1930s.

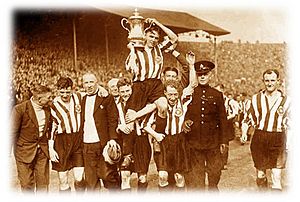

By 1936, Sunderland AFC had won the league six times. They won their first FA Cup in 1937.

When World War II started in 1939, Sunderland was a main target for German Luftwaffe bombing. These raids killed 267 people and destroyed local factories. Also, 4,000 homes were damaged or destroyed.

Many old buildings still stand despite the bombing. These include Holy Trinity Church (1719), St Michael's Church (now Sunderland Minster), and St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth (partly from 674 AD). St Andrew's Church, Roker is known for its Arts and Crafts Movement style. It has work by William Morris and others. St Mary's Catholic Church is the city's oldest Gothic revival church. After the war, more homes were built. The town grew in 1967. Nearby places like Ryhope, Silksworth, Herrington, South Hylton, and Castletown became part of Sunderland. Sunderland AFC won its only major trophy after World War II in 1973, their second FA Cup.

Shipbuilding ended in 1988, and coal-mining in 1993. This followed a crisis in the mid-1980s when 20% of local workers were jobless.

Electronic, chemical, paper, and car manufacturing grew in the 1980s and 1990s. The service industry also expanded. This helped fill jobs lost from heavy industries. In 1986, Japanese car maker Nissan opened its Nissan Motor Manufacturing UK factory in Washington. It has become the UK's largest car factory.

Becoming a City

Sunderland became a city in 1992. Like many cities, it has different areas with their own histories. These include Fulwell, Monkwearmouth, Roker, and Southwick on the north side of the Wear. On the south side are Bishopwearmouth and Hendon. From 1990, the riverbanks were rebuilt. New homes, shops, and business centers appeared on old shipbuilding sites. The National Glass Centre and a new University of Sunderland campus were also built. The old Vaux Breweries site was cleared for new projects.

After 99 years at Roker Park stadium, the city's football club, Sunderland AFC, moved. In 1997, they moved to the 42,000-seat Stadium of Light. It is on the banks of the River Wear. At the time, it was the largest stadium built by an English football club since the 1920s. It has since been made bigger to hold nearly 50,000 people.

On March 24, 2004, the city chose Benedict Biscop as its patron saint. In 2018, a finance company ranked Sunderland as the best place to live and work in the UK. That same year, it was ranked one of the top 10 safest cities in the UK.

How Sunderland is Governed

Sunderland is governed by one main local council: Sunderland City Council. Most of the city area is not divided into smaller parishes. However, a small part on the southern edge is in the parish of Burdon. The city council works from City Hall on Plater Way. This building opened in 2021. Before that, the council was at the Civic Centre, built in 1970.

Sunderland's motto is Nil Desperandum Auspice Deo. This means Under God's guidance we may never despair. The city area had 274,200 people in 2021.

How the City Was Run Over Time

The original Sunderland settlement was part of the old Bishopwearmouth parish in County Durham. It was an ancient borough with a charter from 1179. This first borough was small. It was on the south side of the River Wear's mouth. In 1634, the borough got another charter. This allowed it to have a mayor and officially named the town Sunderland. In 1719, this area became a separate parish from Bishopwearmouth.

The old borough's powers were small. It didn't have its own courts or many city duties. In 1810, a separate group was set up. They were in charge of paving, lighting, and cleaning streets. They also provided a watch and improved the market. In 1832, a parliamentary borough (voting area) of Sunderland was created. It covered Sunderland, Bishopwearmouth, Monkwearmouth, and Southwick.

In 1836, Sunderland became a municipal borough. This made its local government like most others in the country. Its borders were made larger to match the voting area. However, they were later made smaller again. In 1851, the group that managed streets was closed. Their jobs went to the council.

When county councils started in 1889, Sunderland was big enough to run its own services. So, it became a county borough, separate from the new Durham County Council. The city's borders grew several times. In 1967, it gained places like North Hylton, South Hylton, and Ryhope.

In 1974, the county borough was replaced by a larger metropolitan borough. This was within the new county of Tyne and Wear. The borough gained Hetton-le-Hole, Houghton-le-Spring, and Washington.

From 1974 to 1986, the city council was a local authority. The Tyne and Wear County Council provided county-level services. But the county council was closed in 1986. The city council then took on those jobs. Some jobs are shared with other areas in Tyne and Wear. Tyne and Wear still exists as a ceremonial county but has no government jobs since 1986. Sunderland became a city in 1992.

Sunderland will join the North East Mayoral Combined Authority in May 2024.

Voting in Sunderland

For many years, Sunderland has strongly supported the Labour Party. As of 2021, three Labour Members of Parliament represent Sunderland in the House of Commons. These are Bridget Phillipson, Julie Elliott, and Sharon Hodgson.

| Houghton and Sunderland South | Sunderland Central | Washington and Sunderland West |

|---|---|---|

| Bridget Phillipson | Julie Elliott | Sharon Hodgson |

|

|

|

| Labour Party | Labour Party | Labour Party |

In the 2016 vote on European Union membership, Sunderland voted to leave by 61%. This was a surprisingly high number. Some newspapers have called Sunderland a key city for Brexit.

Sunderland's Geography

Much of Sunderland is on low hills near the coast. It is about 80 meters (260 feet) above sea level. The River Wear divides the city. It flows through a deep valley, called the Hylton gorge in parts. Smaller streams also run through the suburbs. Three road bridges connect the north and south parts of the city. These are the Queen Alexandra Bridge, the Wearmouth Bridge, and the Northern Spire Bridge. West of the city, the Hylton Viaduct carries the A19 road over the Wear.

The city has many public parks. Some are old, like Mowbray Park, Roker Park, and Barnes Park. In the early 2000s, Herrington Country Park opened near Penshaw Monument. The city's parks have won awards for keeping natural areas nice. They won the Britain in Bloom award in 1993, 1997, and 2000.

About 70% of the city's people live on the south side of the river. 30% live on the north side. The city area reaches the sea at Hendon and Ryhope in the south and Seaburn in the north.

Green Spaces

The city area is surrounded by the Tyne and Wear Green Belt. This is a protected area of countryside. Its goals are to:

- Stop Sunderland's built-up area from spreading too much.

- Protect the city's countryside from being built on.

- Help rebuild the city's urban areas.

- Keep the special look of Springwell Village.

- Stop Sunderland from joining with Tyneside, Washington, Houghton-le-Spring, and Seaham.

Within the Sunderland area, many places are in the green belt. These include parts of the River Don and Wear basins, golf courses, Herrington Country Park, and Penshaw Hill.

Weather in Sunderland

Sunderland has a mild oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb). It is in the rain shadow of the Pennines mountains. This means it gets less rain than other cities in Northern England. The nearby North Sea makes the climate milder. Summers are cool, and winters are mild for its location. The closest weather station is in Tynemouth, about 8 miles (13 km) north. Sunderland's coast is likely a bit milder. Another nearby station in Durham has warmer summer days and colder winter nights because it's inland.

| Climate data for Tynemouth, 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45.5 (1.79) |

37.8 (1.49) |

43.9 (1.73) |

45.4 (1.79) |

43.2 (1.70) |

51.9 (2.04) |

47.6 (1.87) |

59.6 (2.35) |

53.0 (2.09) |

53.6 (2.11) |

62.8 (2.47) |

52.9 (2.08) |

597.2 (23.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.8 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 8.6 | 9.2 | 8.1 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 10.1 | 109.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 61.1 | 81.6 | 117.7 | 149.9 | 191.7 | 183.0 | 185.7 | 174.9 | 141.1 | 106.2 | 70.4 | 51.9 | 1,515 |

| Source: Met Office | |||||||||||||

People of Sunderland

2021 Census Data

In 2021, the built-up area of Sunderland had 168,315 people. The wider city area had 274,200 people. The 2011 census had a larger definition of the Sunderland built-up area. It included all built-up areas in the city and some outside, like Chester-le-Street.

The table below shows the different ethnic groups in Sunderland compared to the North East England region.

| 2021 Census Ethnic Groups | White | Asian,Asian British,Asian Welsh | Black,Black British,Black Welsh,Caribbean or African | Mixed or Multiple ethnic groups | Other ethnic groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunderland | 94.6% | 3.0% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.5% |

| North East England | 93.0% | 3.7% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.0% |

Most of the non-white population lives in Sunderland East. Specifically, Hendon and Millfield have more Bangladeshi and Indian people. There is also a notable Chinese population in these areas. Sunderland West has Indian, Pakistani, and other Asian groups. Sunderland North has a large Chinese population, especially in St. Peter's. This is likely because of the university students.

- 147 nationalities are at the university.

- 51.27% of students are White, 13.92% Asian, 12.78% Asian Other, and 5.12% Black African. Other groups are smaller.

While different ethnic groups live in certain areas, Sunderland is not very diverse overall. So, it's hard to say if any groups are truly separated.

Religion in Sunderland

| Denomination | Top tier | 2nd | 3rd | 4th |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church of England | Province of York | Diocese of Durham | Archdeaconry of Sunderland | Deanery of Wearmouth |

| Roman Catholic | Archdiocese of Liverpool | Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle | Sunderland and East Durham Vicariate | |

| Methodist | District of Newcastle-upon-Tyne | Circuit of Sunderland | ||

The 2011 census showed that 70.2% of people were Christian. 1.32% were Muslim, 0.29% Sikh, 0.22% Hindu, 0.19% Buddhist, and 0.02% Jewish. 21.90% said they had no religion.

The main building for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Sunderland is the Stake Center.

Sunderland once had a busy Jewish community. It started around 1750 when Jewish traders settled there. They formed a group in 1768. A rabbi from Holland came in 1790. The Jewish community grew fast in the late 1800s. It reached its peak in the mid-1930s with about 2,000 Jewish people. The community has slowly shrunk since the mid-1900s. Many Jewish people left Sunderland for larger Jewish communities in Britain or Israel. The Jewish primary school closed in 1983. The yeshiva moved in 1988. The synagogue on Ryhope Road, opened in 1928, closed in 2006. The Jewish population in Sunderland is still getting smaller. It fell from 114 people in 2001 to 87 in 2021.

In 1998, after Sunderland became a city, the old parish church of Bishopwearmouth (St Michael's) was renamed Sunderland Minster. It was meant to serve the whole city. This was believed to be the first new minster church in England since the Reformation.

Pentecostalism

Reverend Alexander Boddy (1854–1930) became vicar of All Saints' Church, Monkwearmouth in 1884. He was influenced by the 1904–1905 Welsh revival and a Norwegian preacher. In the early 1900s, All Saints, Monkwearmouth, became important for the Pentecostal Movement in Britain.

Sunderland's Economy

After industries declined in the 1970s and early 1980s, Sunderland's economy started to get better. Japanese car maker Nissan opened its Nissan Motor Manufacturing UK factory in 1986. The first Nissan Bluebird car was made that year. The factory and its suppliers are still the biggest employers in the area. They make cars like the Nissan Qashqai, Nissan Juke, and electric Nissan LEAF. In 2012, over 500,000 cars were made each year. It is the UK's largest car factory.

Also in the late 1980s, new service industries moved in. They came to places like the Doxford International Business Park. This brought national and international companies. Sunderland was named one of the top seven "intelligent cities" in the world in 2004 and 2005. This was for its use of information technology.

City Improvements

Since the mid-1980s, Sunderland has been greatly improved. This is especially true around the City Centre and the river.

In 2000, the Bridges shopping center was made bigger. It attracted national chain stores. Then, nearby areas on Park Lane were also redeveloped.

The old shipyards along the Wear were changed. They now have homes, shops, and fun places. These include St Peter's Campus of the University of Sunderland, student housing, the North Haven marina, the National Glass Centre, the Stadium of Light, and Hylton Riverside Retail Park. In 2007, the Echo 24 luxury apartments opened with river views.

Sunderland Corporation's large housing estates from after the war are now owned by Gentoo Group. This is a private company.

The Port of Sunderland, owned by the city council, is planned for future development. It will focus on different types of industry.

Sunderland City Council has plans for many areas to be redeveloped. These plans are supported by Sunderland Arc, a group that helps improve cities.

- Sunniside

In 2004, work started in the Sunniside area. This included a multiplex cinema, a multi-storey car park, restaurants, a casino, and tenpin bowling. The area was first called River Quarter, then Limelight, and in 2008, Sunniside Leisure. Sunniside Gardens were improved. New cafes, bars, and restaurants opened. Fancy apartments were built, like the Echo 24 building.

- Vaux Development and Keel Square

The Vaux brewery closed in 1999. A 26-acre (11 ha) empty site was left in the city center. There was a disagreement over the land. Supermarket chain Tesco bought it in 2001. Sunderland Arc had plans for its redevelopment in 2002. Tesco said they would sell the land if another city center site could be found. Arc hoped to start building in 2010. Arc's plans were approved in 2007. They included offices, hotels, shops, homes, and a new £50 million Crown and Magistrates' court. A central public area under a glass roof was also planned. They hoped to create a lively "evening economy" to go with the city's nightlife. In 2013, Sunderland City Council announced the Keel Square project. This new public space honors Sunderland's sea history. It was finished in May 2015. Building started in 2014.

- Stadium Village

Sunderland A.F.C. has been a big part of the area and its economy since the late 1800s. The club was very successful and well-supported then. Its home, Roker Park, could hold over 70,000 fans. However, the FA Cup win in 1973 was the club's only major trophy after World War II. After being relegated in 1958, the club often moved between the top two divisions. In 1987 and 2018, it was relegated to the third division. The club played at Roker Park for 99 years. It moved because the stadium was too small and needed to be all-seater. The new Stadium of Light opened in 1997. It is in Monkwearmouth by the River Wear. The new stadium held over 42,000 people when it opened. It has since been expanded to about 49,000 seats. Sunderland's high attendance helps the local economy. Even in the third division, average attendance was over 30,000.

The Monkwearmouth Colliery site, north of the river, was redeveloped in the mid-1990s. The Stadium of Light was built there. In 2008, the Sunderland Aquatic Centre opened next to the stadium. It has the only Olympic-size swimming pool between Leeds and Edinburgh. The Sheepfolds industrial area is between the Stadium and the Wearmouth Bridge. Sunderland Arc was buying land there to move businesses and redevelop the site. Plans included more sports facilities to create a Sports Village. Other plans were for a hotel, homes, and a footbridge to the Vaux development.

- Grove and Transport

The Sunderland Strategic Transport Corridor (SSTC) is a planned transport link. It will go from the A19, through the city center, to the port. A big part of the plan was a new bridge, the Northern Spire Bridge. It connects the A1231 Wessington Way (north of the river) with the Grove site in Pallion (south of the river). In 2008, Sunderland City Council asked residents to vote on the bridge design. Choices were a 180-meter (590 ft) cable-stayed bridge (which would raise council tax) or a simple box structure (within budget). The results were unclear. People wanted a cool bridge but didn't want higher taxes. No matter the design, the bridge would land at the old Grove Cranes site in Pallion. Plans for this site focus on new homes, community buildings, shops, and businesses.

Past Industries

Major Industries

Sunderland was once called the "Largest Shipbuilding Town in the World". Ships were built on the Wear from at least 1346. By the mid-1700s, Sunderland was a main shipbuilding town. Sunderland Docks was the center for shipbuilding on Wearside. The Port of Sunderland grew a lot in the 1850s. Robert Stephenson helped design the Hudson Dock. One famous ship was the Torrens. Joseph Conrad sailed on it and started his first novel there. It was one of the most famous ships of its time. It is considered one of the best ships ever launched from Sunderland.

Between 1939 and 1945, the Wear yards launched 245 merchant ships. This was 1.5 million tons, a quarter of all merchant ships made in the UK then. But competition from other countries reduced demand for Sunderland-built ships in the late 1900s. The last shipyard in Sunderland closed on December 7, 1988.

Sunderland, part of the Durham coalfield, has a coal-mining history that goes back centuries. At its busiest in 1923, 170,000 miners worked in County Durham. Workers came from all over Britain, including Scotland and Ireland. After World War II, demand for coal dropped. Mines closed across the area, causing many job losses. The last coal mine closed in 1994. The site of the last mine, Wearmouth Colliery, is now the Stadium of Light. A miner's Davy lamp monument stands outside to honor the mining history. Records about the area's coal mining are kept at the North East England Mining Archive and Resource Centre (NEEMARC).

Smaller Industries

Like coal mining and shipbuilding, foreign competition closed all of Sunderland's glass-making factories. Corning Glass Works, in Sunderland for 120 years, closed in 2007. In January 2007, the Pyrex factory also closed. This ended commercial glass-making in the city. However, there has been a small comeback. The National Glass Centre opened. It gives international glass makers a place to work and sell their art.

In 1855, John Candlish opened a bottleworks. It made glass bottles. He had 6 sites nearby and in Sunderland.

Vaux Breweries started in the town center in the 1880s. For 110 years, it was a major employer. But after many changes in the British Brewing industry, the brewery closed in 1999. Vaux in Sunderland and Wards in Sheffield were part of the Vaux Group. After both breweries closed, it became The Swallow Group, focusing on hotels. This group was bought by Whitbread PLC in 2000. The brewery site is now empty land in the city.

Learning in Sunderland

Sunderland Polytechnic started in 1969. It became the University of Sunderland in 1992. The university now has over 17,000 students. It has two campuses. The City Campus is west of the city center. It has the main library and administration buildings. The St Peter's Riverside Campus is on the north bank of the River Wear. It is next to the National Glass Centre. This campus has the School of Business, Law, Psychology, Computing, Technology, and The Media Centre. In 2006, The Times Higher Education Supplement (THES) named the University of Sunderland the top university in England for student experience. Since 2001, The Guardian has called Sunderland the best new university in England. Government reports showed Sunderland as the best new university for research quality and quantity.

Sunderland College is a further education college. It has campuses at Bede center, Hylton, Doxford International Business Park, and Phoenix House. It has over 14,000 students. Based on exam results, it is one of the most successful colleges. St Peter's Sixth Form College opened in September 2008. It is next to St Peter's Church and the University. This college is a partnership between three Sunderland North schools and City of Sunderland College.

There are 18 secondary schools in Sunderland, mostly comprehensives. Based on exam results, St Robert of Newminster Catholic School in Washington was the most successful. Other successful schools include the Catholic single-sex schools St Anthony's (for girls) and St Aidan's (for boys). Both get good exam results.

There are 76 primary schools in Sunderland. Mill Hill Primary School in Doxford Park is the most successful based on a 'Value Added' measure.

Getting Around Sunderland

Trains and Metro

Sunderland station is served by four train companies:

- Grand Central runs five direct trains to London King's Cross Monday-Saturday (four on Sunday). The trip takes about 3 hours 30 minutes.

- Northern Trains provides services between Nunthorpe, Middlesbrough, Whitby, Newcastle, and Hexham.

- London North Eastern Railway has one daily train to London King's Cross, via Newcastle and York.

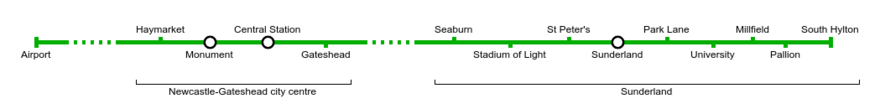

- Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport Executive runs the Tyne & Wear Metro. The city has several stops on the Green line between South Hylton and Newcastle Airport. These include Seaburn, Stadium of Light, and St Peters. The main station is in the city center, with Park Lane Interchange, University, Millfield, and Pallion. Trains run every 12–15 minutes.

Newcastle is a 30-minute Metro or train ride from Sunderland city center. From Newcastle, you can get trains to London King's Cross every half hour (about 2 hours 45 minutes). There are also regular trains to Edinburgh Waverley, Glasgow Central, Leeds, Manchester Piccadilly, Liverpool Lime Street, Birmingham New Street, and beyond.

Sunderland station opened in 1879. It was fully redesigned for England's 1966 World Cup to help fans get to Roker Park. It is underground and became part of the Tyne & Wear Metro in 2002.

In March 2014, Metro owner Nexus suggested extending the network. This would be an 'on-street' tram link. It would connect north to South Shields and west to Doxford Park.

| Operators | Services | Lines | Terminus | Other stations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Trains | An hourly service | Durham Coast Line (DCL), Tyne Valley Line and Esk Valley Line | Hexham and Nunthorpe | Newcastle, Hartlepool and Middlesbrough |

| Grand Central Trains | Five (four on Sunday) trains per day | DCL (south), Northallerton–Eaglescliffe Line and the East Coast Main Line (ECML) | It is a terminus and London Kings Cross | Eaglescliffe, Northallerton, Thirsk and York |

| London North Eastern Railway | A single daily weekday service | DCL (north) and ECML | It is a terminus and Kings Cross | Peterborough (London-bound only), York, Darlington, Durham and Newcastle |

| Tyne and Wear Metro | Up to five (four on evening and Sunday services) trains per hour on | Green Line | Newcastle Airport and South Hylton | Newcastle |

Roads Around Sunderland

There are five main roads that connect the city:

- The city's main road is the A19. It is a dual carriageway running north-to-south west of the city. It crosses the River Wear at Hylton. The road links Doncaster with north of Newcastle upon Tyne and the A1 to Edinburgh. It passes Hartlepool, Stockton-on-Tees, Middlesbrough, and York. The A19 used to go through Sunderland city center. A bypass was built in the 1970s, and the old route became the A1018.

- The A690 Durham Road ends in the city center. It runs to Crook, County Durham, passing through the city of Durham.

- The A1231 (Sunderland Highway) starts in the city center. It crosses the Queen Alexandra Bridge and runs west through Washington to the A1. Most of this road is a fast dual carriageway.

- The A1018 and A183 roads both start in South Shields. They enter Sunderland from the north and then join to cross the Wearmouth Bridge. The A1018 goes straight from Shields to Sunderland. The A183 follows the coast. After the bridge, the A1018 goes south of Sunderland and joins the A19. The A183 becomes Chester Road and goes west out of the city to the A1 at Chester-le-Street. In autumn 2007, the Southern Radial Route opened. This bypasses the A1018 through Grangetown and Ryhope. This area often had traffic jams. The bypass starts south of Ryhope and runs along the cliffs into Hendon, mostly avoiding homes.

The Sunderland strategic transport project is improving the city's roads. It will create a continuous dual carriageway between the A19 and the Port of Sunderland. It also includes the Northern Spire bridge over the Wear.

Buses in Sunderland

Most bus services in Sunderland are run by Stagecoach in Sunderland and Go North East. A few services are by Arriva North East. Long-distance buses are mainly run by National Express and Megabus.

A large transport interchange at Park Lane opened on May 2, 1999. It is the busiest bus and coach station in Britain after Victoria Coach Station in Central London. It has won awards for its design.

A new Metro station was built under the bus station. It opened in 2002 as part of the extension to South Hylton.

Cycling Routes

There are many cycle routes in and around Sunderland. The National Cycle Network National Route 1 goes from Ryhope in the south, through the city center, and along the coast to South Shields. Britain's most popular long-distance cycle route – The 'C2C' Sea to Sea Cycle Route – often starts or ends when cyclists dip their wheel in the sea at Roker beach. The 'W2W' 'Wear-to-Walney' route and the 'Two-Rivers' (Tyne and Wear) route also end in Sunderland.

Airports Near Sunderland

Newcastle Airport is a 55-minute Metro ride from Sunderland city center. A Metro train connects to the airport every 12–15 minutes until about 11 pm, every day.

Teesside International Airport can be reached in less than an hour by car.

Each year, on the last weekend in July, the city hosted the Sunderland International Airshow. It took place mainly along the sea front at Roker and Seaburn.

Port of Sunderland

The Port of Sunderland is the second largest port owned by a city in the United Kingdom. The port has 17 quays. They handle goods like wood products, metals, steel, and oil. It also handles ships that supply offshore platforms and has ship repair facilities. The river berths are deep and affected by tides. The South Docks are entered through a lock.

Sunderland's Culture

Local Talk

The way people speak in Sunderland is called Mackem. It has many unique words and pronunciations. The Mackem dialect comes from the language spoken by the Anglo-Saxon people. While it sounds a lot like Geordie (spoken in Newcastle), there are clear differences.

A few Sunderland words:

- Nee – No

- Bosh – Problem

- Marra – Mate

- Ha'way – Come on (different from Geordie's Howay)

- Knack – Hurt

- Git – Very (used to emphasize, so 'very good' is 'git good')

- Claes – Clothes

Things to See and Do

Popular places to visit in Sunderland include the 14th-century Hylton Castle and the beaches of Roker and Seaburn. The National Glass Centre opened in 1998. It shows Sunderland's long history of making glass.

Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens, on Borough Road, was the first museum outside London funded by a city. It has a large collection of local Sunderland Lustreware pottery. The City Library Arts Centre used to have the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art. The library moved to the Museum and Winter Gardens in 2017. The Gallery for Contemporary Art moved to Sunderland University.

Every year, the city holds a large Remembrance Day service. In 2006, it was the largest in the UK outside London.

Sunderland also has an annual Restaurant Week. City center restaurants offer great food at low prices.

Books and Art

Lewis Carroll often visited the area. He wrote most of Jabberwocky at Whitburn. He also wrote "The Walrus and the Carpenter" there. Many believe parts of the area inspired his Alice in Wonderland stories. These include Hylton Castle and Backhouse Park. There is a statue of Carroll in Whitburn library. Carroll also visited Holy Trinity Church in Southwick. His connection with Sunderland is shown in Bryan Talbot's 2007 graphic novel Alice in Sunderland. More recently, Sunderland-born Terry Deary wrote the Horrible Histories books. Other writers like thriller author Sheila Quigley are also from Sunderland.

The painter L. S. Lowry often stayed at the Seaburn Hotel in Sunderland. Many of his paintings of seascapes and shipbuilding are based on scenes from the River Wear. The Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art and Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens show art from new and famous artists. The museum has a large collection of Lowry's work. The National Glass Centre also shows many glass sculptures.

Music, Dance, and Kites

Musicians from Sunderland who became famous include Dave Stewart from the Eurythmics. All four members of Kenickie are also from Sunderland. Their singer, Lauren Laverne, later became a TV presenter. Recently, Sunderland's underground music scene has helped bands like Frankie & the Heartstrings, the Futureheads, and Field Music.

Other Mackem musicians include punk rockers the Toy Dolls and Red Alert. The lead singer of Olive, Ruth Ann Boyle, is also from Sunderland.

In May 2005, Sunderland hosted BBC Radio 1's Big Weekend concert at Herrington Country Park. 30,000 people attended. Bands like Foo Fighters and Chemical Brothers played.

The Sunderland Stadium of Light, home to Sunderland AFC, is a major concert venue. Famous acts like Oasis, Take That, Pink, and Coldplay have played there. The Empire Theatre also hosts music acts. Independent, a city-center nightclub and music venue, is popular for underground music.

The Manor Quay, the students' union nightclub at the University of Sunderland, has hosted bands like the Arctic Monkeys and Girls Aloud. In 2009, the club became Campus and hosted N-Dubz and Gary Numan. It has since returned to the university. The old students' union, Wearmouth Hall, hosted Radiohead before closing in 1992.

Since 2009, Sunderland: Live in the City has held many free and ticketed live music events in the city center.

In 2013, local band Frankie and The Heartstrings opened a temporary record store called Pop Recs Ltd. It was only meant to be open for two weeks, but it's still open. It has hosted live shows from bands like the Cribs and the Charlatans.

Sunderland also hosts the free International Festival of Kites, Music and Dance. Kite-makers from around the world come to Northumbria Playing Fields in Washington.

Theatres and Shows

The Sunderland Empire Theatre opened in 1907 on High Street West. It is the largest theatre between Edinburgh and London. It was fully renovated in 2004. The Empire is run by Live Nation. It is the only theatre between Glasgow and Leeds big enough for large West End shows. British comic actor Sid James died on stage there in 1976.

The Bunker is a unique place in Sunderland. You can practice, record, learn, and perform music there. It started as a youth project in 1980. It has hosted bands like The Clash and Bjork. The Bunker has a long history of helping music in the North East.

Independent is a popular music venue in Sunderland. It helps young talent and gives bands a stage for their first shows. It has been open since the early 2000s. It has hosted bands like The Zutons and local heroes like The Futureheads.

The Fire Station is a live music and performance hall. It is next to the Empire Theatre. Sunderland Culture runs it. In 2017, the Sunderland MAC Trust restored Sunderland’s old Central Fire Station (built 1908). It had been empty since 1992. It is now a cultural hub with dance studios, teaching rooms, and a bar. The Fire Station auditorium, with 500 seats or 800 standing places, opened in December 2021.

The Royalty Theatre on Chester Road is home to the amateur Royalty Theatre Group. They put on many low-budget shows. Film producer David Parfitt was part of this group and now supports the theatre.

The Sunniside area has many smaller theatre workshops.

Sister Cities

Sunderland is twinned with:

- Harbin, China

- Saint-Nazaire, France

- Washington, D.C., United States

- Essen, Germany

Sunderland is the only non-capital city twinned with Washington, D.C. This is because it includes the town of Washington. This town is the old home of George Washington's family.

Sports in Sunderland

Football

The city is well known for its love of football.

The football team, Sunderland A.F.C., joined the Football League in 1890. Sunderland fans are among the oldest in England. In 2019, even though they were in EFL League One, Sunderland's average attendance was higher than many big European teams. After being relegated from the FA Premier League and the EFL Championship, as shown in the series Sunderland 'Til I Die, the club played four seasons in EFL League One. It has played in the EFL Championship since the 2022-23 season. The team plays at the 49,000-seat Stadium of Light, which opened in 1997.

Sunderland AFC played at Roker Park for 99 years, starting in 1898. They moved because the stadium was too small and needed to be all-seater.

Sunderland A.F.C. Women is one of the top women's football teams in the North East. They play in the second tier of English women's football.

The city also has three non-league teams: Sunderland Ryhope Community Association F.C., Ryhope Colliery Welfare F.C., and Sunderland West End FC. They play at the Ford Quarry Complex.

Rugby and Cricket

Sunderland's amateur Rugby and Cricket clubs are both in Ashbrooke. The Ashbrooke ground opened on May 30, 1887.

Boxing and MMA

Sunderland has a lively combat sports community. There are clubs like Sunderland Amateur Boxing Club and Roker Rough House.

Kiaran MacDonald won silver medals at the 2022 European Championships and Commonwealth Games. Other talented boxers from Sunderland include former Olympians Tony Jeffries and Josh Kelly. Notable Mixed Martial Artists from Sunderland include Andy Ogle and Ross Pearson.

Swimming

On April 18, 2008, the Sunderland Aquatic Centre opened. It cost £20 million to build. It is the only Olympic-sized 50-meter pool between Leeds and Edinburgh. It has six diving boards.

The Crowtree Leisure Centre has hosted important boxing matches and snooker championships. In September 2005, BBC TV showed international boxing matches with local boxers. Tony Jeffries became Sunderland's first Olympic medalist. He won a bronze medal in boxing at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games.

Athletics

In 2023, Sunderland hosted the British part of the World Triathlon Championship Series. Elite athletes competed in swimming, biking, and running. The Roker beach front welcomed triathletes and thousands of amateur participants.

Sunderland Harriers Athletics Club is at Silksworth Sports Complex. Runner Gavin Massingham represented the club in 2005.

The first Sunderland city 10 km race was held in 2011. Over 1500 people took part. By 2021, the Sunderland City Runs welcomed 4000 participants. They ran different distances through the city streets.

On June 25, 2006, the first Great Women's Run took place along Sunderland's coast. Olympic silver medalists from Ireland and Ethiopia ran. The race quickly became a yearly event. In 2009, it was relaunched as the Great North 10K Run, allowing men to take part.

Famous People from Sunderland

See also

In Spanish: Sunderland para niños

In Spanish: Sunderland para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |