Lustreware facts for kids

Lustreware is a special kind of pottery or porcelain. It has a shiny, metallic surface that looks like it shimmers or changes color in the light. This effect is created by adding tiny amounts of metal to the pottery's glaze. The pottery is then fired a second time at a lower temperature. This process makes the metal stick to the surface, giving it a beautiful, reflective shine.

The idea of making lustreware started a long time ago in Mesopotamia (which is modern-day Iraq). This was in the early 800s. At first, the pottery had mostly geometric patterns. By the 900s, designs often featured one or two large figures.

Lustreware making then became very popular in Egypt after the Fatimid Caliphate took over in 969. It was a major center for this art until 1171. After that, many potters might have moved to Syria and Persia, where lustreware then appeared. Later, big wars caused by the Mongols and Timur disrupted these pottery industries.

The technique also spread to al-Andalus (the Islamic part of Spain). Here, a type called Hispano-Moresque ware became famous. It was mostly made in Christian Spain, especially in the Valencia region, like in Manises.

Around 1500, lustre appeared in Italian pottery called maiolica. Two towns, Gubbio and Deruta, became known for it. Gubbio was famous for a rich ruby-red color. The art was revived in England and other European countries in the late 1700s. Potters had to mostly figure out the techniques again. Meanwhile, Persian lustreware also had a comeback between 1650 and 1750. They made elegant vases and bottles with detailed plant designs.

The shiny lustre effect is a final coating put over the main ceramic glaze. It's fixed by a quick second firing. Tiny amounts of metal (usually silver or copper) are mixed with clay or ochre to make a paint. This paint is fired in a special oven that has less oxygen. The heat softens the first glaze and breaks down the metal compounds. This leaves a very thin layer of metal fused with the main glaze. Lustreware usually has only one color per piece. Gold-like colors from silver were the most common historically.

Contents

How Lustreware is Made

To make classic lustreware, a mix of metal salts (from copper or silver), vinegar, ochre, and clay is used. This mixture is painted onto a pottery piece that has already been fired and glazed.

The pot is then fired again in a special oven called a kiln. This second firing happens at about 600 °C (1,112 °F). The special atmosphere in the kiln changes the metal salts into tiny metal particles. These particles create the metallic, shiny look on the pottery.

Making lustreware has always been costly and a bit tricky. It always needs two firings. Sometimes, expensive metals like silver or platinum were used. The thin lustre layer can also be delicate. Many types of lustreware can be easily scratched. They can also be damaged by acids, even mild ones found in food. Because of this, lustreware was often used for display rather than for everyday eating. By the 1800s, it became a bit cheaper. Sometimes, the shiny effect didn't work perfectly on all parts of a piece. But these pieces were still sold.

Early Islamic Lustreware

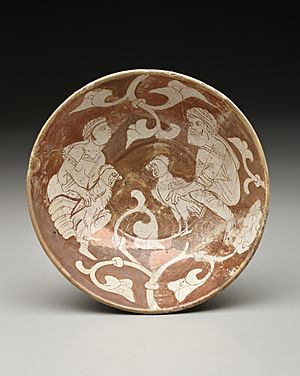

The first lustreware pottery was likely made in modern-day Iraq around the early 800s. This was during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate, near cities like Baghdad. Most pieces were small bowls. However, parts of larger pots have been found. These early pieces were special because they used three or four different lustre colors. Later lustreware usually used fewer colors.

Early Islamic lustreware was mainly made in southern Mesopotamia during the 800s and 900s. For example, in the Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia, the upper part of the prayer niche (mihrab) has shiny lustreware tiles. These tiles are from 862-863 and probably came from Mesopotamia. The shiny look, especially like gold, made lustreware very appealing. These bowls were painted with beautiful patterns and designs. Some pieces were even signed by the artists.

Abbasid lustreware was traded widely in the Islamic world. Cities like Baghdad were part of the Silk Road trade routes. Goods moved between Iraq and China, leading to new art ideas and sharing of pottery techniques.

Some Abbasid lustreware shows figures, while other pieces have plant designs. Some even combine both. At this time, artists liked to cover the entire surface of objects with decorations. As lustreware spread to other places, less decoration was sometimes used. Abbasid lustreware could have many colors (polychrome) or just one (monochrome). The colors could look different depending on the light. Potters often decorated multi-colored bowls with plant and geometric patterns. Single-color bowls usually had large figures in the center.

Lustreware in Fatimid Egypt

The Fatimid rulers in Egypt were very rich and loved fancy things. This made their time a great period for lustreware. It was the only luxury pottery made then. The pottery itself was often made from rough clay. But the painting on it was very fine and lively. The artists might have bought plain glazed pots from other makers and then added their special lustre designs. The decorations were very varied. They mixed ideas from earlier Mesopotamian art with influences from North Africa and Sicily.

Only two pieces can be dated for sure, thanks to names written on them. Both are from the early period, during the rule of Caliph al-Hakkim (996-1021). During this time, the style was still developing. But a new style with brighter, warmer colors probably started by the mid-1000s. Gold, red, and orange colors reminded people of the sun and were seen as lucky. Some animals painted on the pottery were also considered good luck.

Lustreware in Persia

Lustreware began to be made in Persia when it was part of the Seljuk Empire. The 50 years from 1150 saw big improvements in Iranian pottery. The clay body and glazes became much better. This allowed for thinner pottery walls and some see-through qualities, like Chinese porcelain. Chinese porcelain was already imported and was the main competition for local fine pottery.

This improved "white ware" body was used for many decoration styles. Besides lustreware, the most luxurious type was mina'i ware. This used many colors painted over the glaze. It also needed a light second firing. Some pieces even combined both lustre and mina'i techniques. The oldest dated Persian lustre piece is from 1179. It's thought that artists from Egypt might have come to Persia. However, they probably painted on local pottery shapes. The main lustre color used was gold.

Lustreware was definitely made in Kashan, and it might have been the only place it was made there. The Mongol invasion in 1224 seemed to slow down production until the 1240s. But it continued, with little change in style. This was different from mina'i ware, which almost disappeared after 1219.

A large part of Persian lustreware was made into tiles. These tiles were usually star-shaped. They had animal or human figures in the middle, often one or two. There were also decorations around the edges and sometimes writings. Eight-pointed stars were common, but six-pointed ones were too. These tiles were made in large numbers. They were cemented to walls and have survived better than pottery vessels. The word kashi or kashani became the common Persian word for a tile. The painting often mixed blue underglaze with the shiny lustre. The figures on tiles were sometimes painted more quickly than those on vessels.

Tile and vessel making continued under the Mongol Ilkhanids. The quality of the pottery, glaze, and painting sometimes went down. The designs became a bit heavier. Lustre production seems to have stopped around 1339, perhaps because of the Black Death plague. Lustre on vessels was already declining from about 1300. The Ilkhanids started using lustre more as a rich addition to other colors, rather than the main focus.

After a break of several centuries, Persian lustreware was revived in the Safavid period, starting around the 1630s. This new style was different. It typically made small pieces with dark copper designs over a dark blue background. Unlike other Persian pottery of that time, these used traditional Middle Eastern shapes and decorations. They did not copy Chinese designs. The designs featured plants and animals. They usually flowed freely over the whole surface. Production was never huge. It mostly happened from about 1650 to 1750. Some lower quality pieces were made into the 1800s. It's often thought to have been made in Kirman, but there's no strong proof.

Lustreware in Syria

Like in Persia, lustreware started in Syria when Egyptian potters spread out around 1170. The painting style continued to use Egyptian ideas and subjects. But the clay and pottery shapes were different. This suggests local potters worked with the artists who moved there. This first type is called Tell Minis ware. The designs were often free-flowing. They showed things like sun-faces, fish, crescent moons, and court figures. These were seen as good omens.

Tell Minis ware stopped around 1200. Around that time, a new and very different type of production began at Raqqa. This lasted until the Mongols destroyed the city in 1259. Lustre was just one type of finish used on some vessels made there. In Raqqa ware, the painting mostly featured plant forms and writings. These were arranged in a structured way, giving them a dignified look. The pottery did not seem to be made for royal courts. The glazes were either clear, showing an off-white body, or had various dark colors. The mix of these dark glazes and lustre created a mysterious look. This probably influenced later Spanish and Italian lustreware. Some Syrian examples have been found in Europe.

After Raqqa fell, the lustre technique later appeared in Damascus. This continued until Timur attacked the city in 1401, ending Syrian lustreware. Damascus wares also reached Europe. In Spain and Italy, records from the 1400s describe local lustreware using terms like "Damascus style." The similar painting styles suggest some artists might have moved from Syria to Europe.

-

The Mihrab (prayer niche) in the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia. It has 800s lustreware tiles.

-

A Hispano-Moresque dish from Manises, Spain, 1400-1460.

-

A Hispano-Moresque bowl from Andalusia, Spain, 1500-1550.

-

A Safavid wine jug from Iran, late 1600s. It might have had matching cups.

Modern Lustreware

A different kind of metallic lustre was made in England. It made pottery look like it was made of silver, gold, or copper. Silver lustre used a new metal called platinum. Around 1800, John Hancock figured out how to use platinum for this. Very small amounts of powdered gold or platinum were mixed into liquids. This mixture was painted onto the glazed pottery. Then, it was fired in a special oven. This left a thin film of platinum or gold.

Platinum made pottery look like solid silver. It was used for middle-class families to make tea sets that looked like silver ones, from about 1810 to 1840. Depending on how much gold was used and the color of the pottery underneath, many colors could be made. These included pale rose, lavender, copper, and gold. Gold lustre could be painted or stenciled. It could also be applied using a "resist" technique. In this method, a design was painted with glue. Then, the lustre was applied over it. The glue was washed off before firing, leaving the design in the original pottery color.

Lustreware became popular in Staffordshire pottery during the 1800s. Companies like Wedgwood also used it. Wedgwood introduced pink and white lustreware that looked like mother of pearl. They also made silver lustre from 1805. In 1810, Peter Warburton patented a way to print designs in gold and silver lustre. Sunderland lustreware in North East England is famous for its mottled pink lustreware. It was also made in Leeds, Yorkshire.

Wedgwood lustreware from the 1820s led to many copper and silver lustreware pieces being made in England and Wales. Cream pitchers with detailed spouts and handles were very common. They often had decorative bands in dark blue, cream yellow, pink, and sometimes dark green and purple. Raised, colorful patterns showing countryside scenes were also made. Sometimes, sand was added to the glaze for texture. Pitchers came in many sizes, from small creamers to large milk pitchers. Small coffeepots and teapots were also made. Tea sets came later, usually with creamers, sugar bowls, and slop bowls.

Large pitchers with printed scenes to remember events appeared around the mid-1800s. These were purely for decoration. Today, they are very valuable because of their historical connections. Delicate lustre that looked like mother of pearl was made by Wedgwood and at Belleek in the mid-1800s.

During the Aesthetic Movement, artist William de Morgan brought back lustreware in art pottery. He was inspired by old majolica and Hispano-Moresque lustreware. He created beautiful, bold designs.

In the United States, copper lustreware became popular because of its shine. When gaslights became available, rich people liked to place groups of lustreware on mirrors. These were used as centrepieces for dinner parties. The gaslights made the pottery shine even more.

Images for kids

-

A dish from Gubbio, Italy, 1530–40, showing Mary Magdalene on Italian maiolica.

-

A bowl from Kashan, Iran, around 1260-1280.

See also

In Spanish: Loza dorada para niños

In Spanish: Loza dorada para niños

- Eosin

- List of pottery terms

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |