Joseph Paxton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

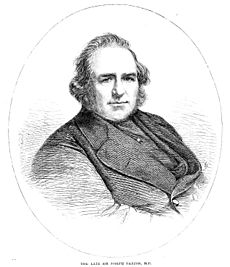

Sir Joseph Paxton

|

|

|---|---|

Sir Joseph Paxton

|

|

| Born | 3 August 1803 Bedfordshire, England

|

| Died | 8 June 1865 (aged 61) Sydenham, London, England

|

| Occupation | Architect |

Sir Joseph Paxton (born August 3, 1803 – died June 8, 1865) was a very talented English gardener, architect, engineer, and even a Member of Parliament. He is most famous for designing the amazing the Crystal Palace and for growing the Cavendish banana, which is the most popular type of banana eaten in many parts of the world today.

Contents

Early Life of Joseph Paxton

Joseph Paxton was born in 1803 in Milton Bryan, Bedfordshire. He was the seventh son in a farming family. When he was 15, he started working as a garden boy at Battlesden Park. After moving around a bit, he got a job in 1823 at the Horticultural Society's Chiswick Gardens.

Paxton's Time at Chatsworth House

The Horticultural Society's gardens were very close to the gardens of William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire, at Chiswick House. The Duke was impressed by young Paxton's skills and energy. So, he offered the 20-year-old Paxton the important job of head gardener at Chatsworth. At that time, Chatsworth had one of the most beautiful gardens in England.

Even though the Duke was in Russia, Paxton quickly traveled to Chatsworth. He arrived very early in the morning and, by his own account, explored the gardens, got the staff working, ate breakfast, and even met his future wife, Sarah Bown, all before nine o'clock! He married Sarah in 1827. She was very good at managing his business, which allowed him to focus on his many creative ideas.

Paxton and the Duke became good friends. The Duke recognized Paxton's many talents and helped him become very well-known.

One of Paxton's first big projects at Chatsworth was to redesign the garden around a new part of the house. He also expanded Chatsworth's collection of cone-bearing trees into a large, 40-acre (160,000 m2) arboretum, which is like a tree museum. This arboretum is still there today. Paxton became very skilled at moving large, mature trees. He even moved one that weighed about eight tons! Other big projects at Chatsworth included a rock garden, the Emperor Fountain, and rebuilding the nearby village of Edensor. The Emperor Fountain was built in 1844. It was incredibly tall, twice the height of Nelson's Column in London. To make it work, a large lake had to be created on the hill above the gardens, which involved digging out a huge amount of earth.

Paxton's Greenhouses

In 1832, Paxton became very interested in greenhouses at Chatsworth. He designed special buildings with "forcing frames" to help fruit trees grow and to cultivate exotic plants like pineapples. Back then, glass houses were quite new, and the ones at Chatsworth were old and falling apart. After trying different things, he designed a new type of glass house. It had a special "ridge and furrow" roof that let in the most sunlight. This design was a very early version of the modern greenhouse we see today.

The next big building at Chatsworth was for the first seeds of the Victoria regia lily. This giant water lily came from the Amazon in 1836. Although other places had tried, they couldn't get it to flower. In 1849, a seedling was given to Paxton to try at Chatsworth. He gave it to a young gardener named Eduard Ortgies. Within two months, the lily's leaves were 4.5 ft (1.4 m) wide, and a month later, it flowered! It kept growing, so they had to build a much larger house for it, called the Victoria Regia House.

Paxton was amazed by the lily's huge leaves, calling them "a natural feat of engineering." He realized the structure of the leaves, with their strong ribs, could be used to design buildings. He even tested this idea by floating his daughter Annie on one of the lily's leaves! The secret was how the strong ribs connected with flexible cross-ribs, making the leaf very sturdy. After many experiments, he came up with a glasshouse design that later inspired the famous Crystal Palace.

Paxton's new conservatory design used a cheap and light wooden frame. The ridge-and-furrow roof let in more light and helped drain rainwater. He also used hollow pillars that doubled as drain pipes and designed special rafters that acted as gutters. All the parts were made in advance, like modular buildings. This meant they could be produced in large numbers and put together quickly to create buildings of different designs.

In 1836, Paxton started building the Great Conservatory, also called the Stove. It was a huge glasshouse, 227 ft (69 m) long and 123 ft (37 m) wide. It was designed by the Duke's architect, Decimus Burton. The columns and beams were made of cast iron, and the arched parts were made of laminated wood. At the time, it was the largest glass building in the world! The glass sheets used were the biggest available, 4 ft (1.2 m) long, made specially for Paxton. The building was heated by eight boilers using seven miles (11 km) of iron pipes and cost over £30,000. It even had a central path where the Queen was driven through, lit by twelve thousand lamps. However, it was very expensive to keep warm, and after the plants died during World War I, it was taken down in the 1920s.

In 1848, Paxton also created the Conservative Wall, a glass house 331 ft (101 m) long and 7 ft (2.1 m) wide.

The Amazing Crystal Palace

The Great Conservatory was like a practice run for Paxton's greatest work: The Crystal Palace. This huge building was made for the Great Exhibition of 1851. He used the same ideas of prefabricated glass and iron structures that he had developed at Chatsworth. These techniques were possible because new technology allowed for better glass and cast iron to be made, and a tax on glass had been removed, making it cheaper.

In 1850, the people organizing the Great Exhibition had a big problem. They had received 245 designs for a building, but none were quite right, and all would take too long to build. People were also upset about building something permanent in Hyde Park.

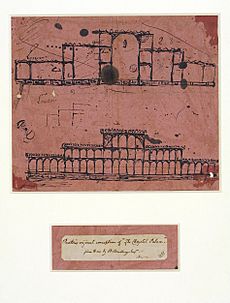

Paxton was in London for a meeting about the Midland Railway. He happened to mention an idea he had for the exhibition hall. He was encouraged to quickly draw up some plans, in just nine days! It's said that during a railway board meeting, he spent most of his time drawing on a piece of blotting paper. At the end of the meeting, he showed his first sketch of the Crystal Palace, inspired by the Victoria Regia House. This original sketch is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

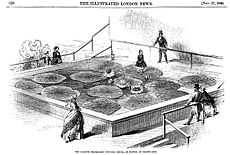

He finished the plans and showed them to the Exhibition Committee. Some members were against it because another design was already being planned. So, Paxton decided to share his design with the public by publishing it in the Illustrated London News. Everyone loved it!

What made the Crystal Palace so special was its new, revolutionary design. It was made of many parts that were built in advance (prefabricated) and then put together. It used a lot of glass. Workers used special trolleys to put the glass in place very quickly; one person could fix 108 panes in a single day!

The Palace was 1,848 ft (563 m) long, 408 ft (124 m) wide, and 108 ft (33 m) high. It needed 4,500 tons of iron, 60,000 sq ft (5,600 m2) of timber, and over 293,000 panes of glass. Yet, 2,000 men built it in just eight months, and it only cost £79,800. It was unlike any other building and showed off Britain's amazing technology in iron and glass. Paxton worked with Charles Fox for the iron frame and William Cubitt, who led the building committee. All three were honored with knighthoods. After the exhibition, the Crystal Palace was moved to Sydenham, where it stayed until it was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Paxton's Publications

Joseph Paxton also loved to share his knowledge. In 1831, he started a monthly magazine called The Horticultural Register. After that, he published the Magazine of Botany in 1834, the Pocket Botanical Dictionary in 1840, and Paxton's Flower Garden in 1850. He also wrote the Calendar of Gardening Operations. In 1841, he helped start The Gardeners' Chronicle, which is a very famous gardening magazine, and he later became its editor.

Paxton's Political Career

Joseph Paxton was a member of the Liberal political party. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for Coventry from 1854 until he passed away in 1865.

In 1855, he proposed a big plan called the Great Victorian Way. He imagined building a huge covered walkway, similar to the Crystal Palace, in a ten-mile loop around the center of London. This walkway would have included a road, a special railway, homes, and shops.

Later Life and Other Projects

Even though he remained the Head Gardener at Chatsworth until 1858, Paxton also worked on many other projects. Besides the Crystal Palace, he was a director of the Midland Railway. He designed public parks in cities like Liverpool, Birkenhead, Glasgow, and Halifax (the People's Park). He also designed the grounds of the Spa Buildings at Scarborough. In 1845, he was asked to design one of the country's first public cemeteries in Coventry. This became the London Road Cemetery, where a memorial to Paxton was built in 1868.

Between 1835 and 1839, he organized trips to find new plants. Sadly, one of these trips ended in tragedy when two gardeners from Chatsworth drowned in California. He also faced personal sadness when his eldest son died.

In 1850, a wealthy man named Baron Mayer de Rothschild asked Paxton to design Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire. This became one of the grandest country houses built during the Victorian Era. After Mentmore was finished, Baron James de Rothschild, a French cousin, asked Paxton to design Château de Ferrières near Paris, making it "Another Mentmore, but twice the size." Both of these impressive buildings still stand today.

Paxton also designed another country house, a smaller version of Mentmore, in Battlesden near Woburn. This house was later bought and taken down by the Duke of Bedford because he didn't want another large mansion too close to his own home, Woburn Abbey.

In 1860, he also designed a house called Fairlawn for Sir Edwin Saunders, who was Queen Victoria's dentist.

Paxton was highly respected. He was a member of the Kew Commission, which suggested improvements for the Royal Botanic Gardens. He was also considered for the important job of Head Gardener at Windsor Castle.

He became quite wealthy, not just from his job at Chatsworth, but also from successful investments in the railway industry. He retired from Chatsworth when the Duke died in 1858, but he continued to work on various projects, such as the Thames Graving Dock. Joseph Paxton passed away at his home in Sydenham in 1865. He was buried on the Chatsworth Estate in St Peter's Churchyard, Edensor. His wife Sarah stayed at their house on the Chatsworth Estate until her death in 1871.

|

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Paxton para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Paxton para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |