Maximus the Confessor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids SaintMaximus the Confessor |

|

|---|---|

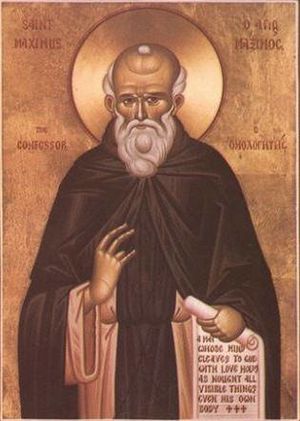

Icon of St. Maximus

|

|

| Confessor, theologian, homologetes | |

| Born | c. 580 Haspin, Golan Heights or Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Died | 13 August 662 Tsageri (modern-day Georgia) |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Catholic Church Anglican Communion Lutheranism |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Feast | 13 August (Gregorian Calendar), 21 January or 13 August (Julian Calendar) |

Maximus the Confessor (also known as Maximos, Maximus the Theologian, or Maximus of Constantinople) was an important Christian monk, theologian, and scholar. He lived from around 580 AD until August 13, 662 AD.

Maximus started his career as a civil servant, even working for the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius. However, he chose to leave politics and become a monk. He studied many different types of philosophy, including the ideas of Plato and Aristotle. Maximus became involved in a big debate about how to understand Jesus. He believed that Jesus had both a human will and a divine will. This idea is called "Dyothelitism."

Maximus is highly respected in both the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. He was exiled and died on August 13, 662, in what is now Georgia. Later, his ideas were officially supported by a major church meeting called the Third Council of Constantinople. He was recognized as a saint soon after his death. He is special because he has two feast days: August 13 and January 21. His title "Confessor" means he suffered for his Christian beliefs but was not killed for them.

Contents

Maximus's Life Story

His Early Years

We don't know much about Maximus's early life before he became involved in big church debates. Some scholars believe he was born into a wealthy family. This would explain why he received such a good education. He studied philosophy, math, and astronomy. It's also why he could become a top assistant to Emperor Heraclius. This was a very powerful job in the Byzantine Empire.

For reasons we don't fully know, Maximus decided to leave his public life. He became a monk at a monastery in Chrysopolis, which was across the water from Constantinople. He later became the abbot, or head, of this monastery.

Moving to Carthage

When the Persians invaded Anatolia, Maximus had to escape. He fled to a monastery near Carthage in North Africa. There, he learned from Saint Sophronius. He studied important Christian writings, especially those about the nature of Jesus. Maximus continued to write about theology and spiritual topics during his long stay in Carthage. Important leaders in the region, like Gregory and George, thought highly of him.

His Trials and Exile

Maximus refused to accept a belief called Monothelitism. This belief said that Jesus only had one will (a divine will), not two (human and divine). Because of his strong beliefs, he was brought to Constantinople in 658 to be tried as a heretic. At that time, the Emperor and the Patriarch (the top church leader) in Constantinople supported Monothelitism. Maximus stuck to his belief that Jesus had both a human and a divine will. He was sent away into exile for four more years. During his trial, he was falsely accused of helping Muslim armies conquer Egypt and North Africa. He strongly denied these accusations.

In 662, Maximus was put on trial again. He was found guilty of heresy once more. After the trial, he was tortured. His tongue was cut out so he could not speak his beliefs, and his right hand was cut off so he could not write. Maximus was then sent to a faraway fortress in modern-day Georgia. He died there soon after, on August 13, 662. The story of Maximus's trials was written down by Anastasius Bibliothecarius.

Maximus's Lasting Impact

Maximus's ideas were later proven right by the Third Council of Constantinople. This important church meeting, held from 680 to 681, declared that Christ did indeed have both a human and a divine will. This meant that Monothelitism was wrong, and Maximus was declared innocent after his death.

Maximus is one of the few Christians who became a saint very soon after he died. His theological ideas becoming official made him very popular. Stories of miracles happening at his tomb also helped people see him as a saint.

Maximus is considered one of the last "Fathers of the Church" recognized by both the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. Pope Benedict XVI even called him a "great Greek doctor of the Church."

Maximus's Ideas and Teachings

Maximus studied the ideas of earlier thinkers like Pseudo-Dionysius. He helped keep alive and explain ancient Greek philosophy, especially the ideas of Plotinus and Proclus.

Maximus's ideas about humanity and God were greatly influenced by Greek philosophy. He taught that humans were made in the image of God. He believed that the goal of salvation is to bring us back into unity with God. This focus on "divinization" or theosis (becoming more like God) is very important in Eastern Christian thought.

Maximus strongly believed that Jesus had two distinct natures, divine and human. This was important to him because he thought that for humans to be fully united with God, God first had to be fully united with humanity in Jesus. If Jesus wasn't fully human, then humans couldn't become fully divine. He also argued that God's becoming human was not dependent on anything else.

Some scholars believe Maximus, like others before him, thought that all souls would eventually be saved and reunited with God. This idea is called apocatastasis or universal reconciliation. While this is debated, some argue he shared this belief with his most advanced students.

Maximus's Writings

Maximus wrote many important books and letters. Here are some of his well-known works:

- Ambigua ad Iohannem ("Difficult Passages Addressed to John")

- Ambigua ad Thomam ("Difficult Passages Addressed to Thomas")

- Capita XV ("Fifteen Chapters")

- Capita de caritate ("Chapters on Charity")

- Capita theologica et oeconomica (Chapters on Theology and the Economy)

- Disputatio cum Pyrrho ("Dispute with Pyrrhus")

- Epistulae I–XLV ("Epistles 1–45")

- Expositio orationis dominicae ("Commentary on the Lord's Prayer")

- Expositio in Psalmum LIX ("Commentary on Psalm 59")

- Liber Asceticus ("On the Ascetic Life")

- Mystagogia ("Mystagogy")

- Maximi Epistola ad Anastasium monachum discipulum ("Letter of Maximus to Anastasius the Monk and Disciple")

- Opuscula theologica et polemica ("Small Theological and Polemical Works")

- Quaestiones et dubia ("Questions and Doubtful Passages")

- Quaestiones ad Thalassium ("Questions Addressed to Thalassius")

- Questiones ad Theopemptum ("Questions Addressed to Theopemptus")

- Testimonia et syllogismi ("Testimonies and Syllogisms")

Texts sometimes attributed to him:

- Scholia – These are comments on earlier writings. Some parts might be by Maximus, but others might be by a different writer.

- Life of the Virgin – This is an early biography of Mary, the mother of Jesus. However, most scholars now believe Maximus did not write this book.

Collections of his works:

- Maximus Confessor: Selected Writings (Classics of Western Spirituality). Ed. George C. Berthold. Paulist Press, 1985. ISBN: 0-8091-2659-1.

- On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ: Selected Writings from St. Maximus the Confessor (St. Vladimir's Seminary Press "Popular Patristics" Series). Ed. & Trans Paul M. Blowers, Robert Louis Wilken. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2004. ISBN: 0-88141-249-X.

- St. Maximus the Confessor: The Ascetic Life, The Four Centuries on Charity (Ancient Christian Writers). Ed. Polycarp Sherwood. Paulist Press, 1955. ISBN: 0-8091-0258-7.

- Maximus the Confessor (The Early Church Fathers) Intro. & Trans. Andrew Louth. Routledge, 1996. ISBN: 0-415-11846-8

- Maximus the Confessor and his Companions (Documents from Exile) (Oxford Early Christian Texts). Ed. and Trans. Pauline Allen, Bronwen Neil. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN: 0-19-829991-5.

- On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua: Volume I, Maximos the Confessor. Ed. and Trans. Nicholas Constas. London: Harvard University Press, 2014. ISBN: 978-0-674-72666-6.

- On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua: Volume II, Maximos the Confessor. Ed. and Trans. Nicholas Constas. London: Harvard University Press, 2014. ISBN: 978-0-674-73083-0.

- The Philokalia: The Complete Text compiled by St Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain and St Makarios of Corinth: Volume II. Ed. and Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware. London: Faber and Faber, 1981. ISBN: 978-0-571-15466-1.

See also

In Spanish: Máximo el Confesor para niños

In Spanish: Máximo el Confesor para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |