Scandinavian Scotland facts for kids

Scandinavian Scotland was a time from the 700s to the 1400s. During this period, Vikings and other Norse people, mostly from Norway, settled in parts of what is now Scotland.

Viking influence began in the late 700s. There was often fighting between the Norse earls of Orkney and the growing sea-based kingdom of the Kingdom of the Isles. This kingdom included parts of Ireland, Dál Riata, and Alba. The King of Norway also often got involved.

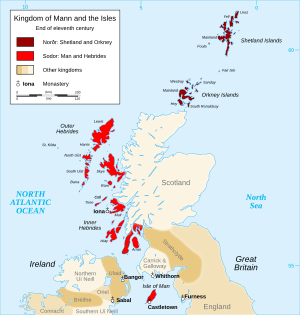

Norse lands included the Northern Isles (Orkney and Shetland), the Hebrides, and islands in the Firth of Clyde. They also controlled parts of mainland Scotland like Caithness and Sutherland.

Records from Scotland about this time are not very detailed. We learn most from old Irish writings and later Norse stories, especially the Orkneyinga saga. Sometimes these sources disagree. However, archaeology is now helping us understand more about life during this period.

There are different ideas about how the Vikings first settled. But it's clear that the Northern Isles were the first to be taken by Vikings. They were also the last lands given up by the Norwegian crown. Thorfinn Sigurdsson ruled in the 1000s and expanded his power into northern mainland Scotland. This might have been when Norse influence was strongest.

Most old names in the Hebrides and Northern Isles were replaced with Norse names. But the Norse also teamed up with native Gaelic speakers. This created a strong Norse–Gael culture. This culture had a big impact in areas like Argyll and Galloway.

Scottish influence grew from the 1200s. In 1231, the line of Norse earls of Orkney ended. After that, Scottish nobles held the title. A failed trip by King Haakon Haakonarson later in the 1200s led to the western islands being given to the Scottish Crown. In the mid-1400s, Orkney and Shetland also became part of Scottish rule.

Even though Vikings are often seen as violent, their expansion might have helped create the Gaelic kingdom of Alba. This kingdom was the start of modern Scotland. The trade, politics, culture, and religion of the later Norse period were also very important.

Contents

Where the Vikings Settled in Scotland

The Northern Isles, called Norðreyjar by the Norse, are the closest parts of Scotland to Norway. These islands were the first to have Norse influence and kept it the longest. Shetland is about 300 kilometers west of Norway. A Viking longship could reach it in 24 hours from Hordaland in good weather. Orkney is 80 kilometers further southwest.

About 16 kilometers south of Orkney is the Scottish mainland. The two most northern parts of mainland Scotland, Caithness and Sutherland, came under Norse control early on. South of these, the entire western coast of mainland Scotland, from Wester Ross to Kintyre, also had a lot of Scandinavian influence.

The Suðreyjar, or "Southern Isles," included:

- The Hebrides (Western Isles):

- The Outer Hebrides, also called the "Long Island." These are about 180 kilometers west of Orkney.

- The Inner Hebrides, including Skye, Islay, Jura, Mull, and Iona.

- The islands in the Firth of Clyde, about 140 kilometers to the south. The biggest are Bute and Arran.

- The Isle of Man, located in the Irish Sea. It is equally far from modern England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.

The whole area from the south of the Isle of Man to the Butt of Lewis (north of the Outer Hebrides) is about 515 kilometers. Norse culture became very strong in this entire region for much of this period. For example, the Norse language likely became as common in the Inner Hebrides as it was on Lewis in the 900s and 1000s.

There was also direct Norse influence in Galloway in southwest Scotland. Until the 1266 Treaty of Perth, Norwegian and Danish foreign policy, and the actions of independent Norse rulers in these areas, greatly affected Scotland as a whole.

Understanding Viking History in Scotland

Written records from the Viking period in Scottish history are very limited. The monastery on Iona kept good records from the mid-500s to the mid-800s. But after 849, when Columba's holy items were moved because of Viking attacks, local written evidence almost disappears for 300 years.

So, most of what we know about the Hebrides and northern Scotland from the 700s to the 1000s comes from Irish, English, or Norse sources. The main Norse text is the Orkneyinga Saga. An unknown Icelander wrote it in the early 1200s. The English and Irish records are from closer to the time. But they might focus more on the south, especially since much of the Hebrides became Norse-speaking. So, dates from this time are often approximate.

Archaeological finds from this period are still few, but they are growing. Toponymy (the study of place names) gives us a lot of information about the Scandinavian presence. Examples of Norse runes also provide useful clues. There are also many stories from the Gaelic oral tradition about this time, but their accuracy is uncertain.

Language and personal names can be tricky. Language is a key sign of culture. But there is little direct proof of what languages were spoken in specific places during this time. Pictish, Middle Irish, and Old Norse were certainly spoken. Some historians think there was a lot of language mixing. Because of this, people sometimes appear with different names in different records.

How Vikings Settled the Land

Sailors from Gaelic and Pictish areas likely knew about Scandinavia before the Viking Age began. This is because sea travel was common around the Hebrides and Orkney in the 600s. Some also suggest that an attack by forces from Fortriu in 681, which "destroyed" Orkney, might have weakened local power. This could have helped the Norse rise to power.

Historians have different ideas about how the Viking Age in Scotland unfolded. Barrett (2008) points out four main theories, none of which are fully proven.

The most common idea is the "earldom hypothesis." This suggests a time of Norse expansion into the Northern Isles. It led to a powerful noble family that lasted into the Middle Ages. This family had a lot of influence in western Scotland and Mann until the 1000s. This story comes from the Norse sagas and some archaeological finds. But some say it overstates Orkney's power in the Suðreyar.

Another idea is the "genocide hypothesis." This claims that the original people of the Northern and Western Isles were wiped out. They were replaced entirely by Scandinavian settlers. This idea is supported by how almost all old place names were replaced by Norse ones. But the place name evidence is from later times, and how this change happened is still debated. Genetic studies show that people from Shetland have equal amounts of Scandinavian male and female ancestry. This suggests that both men and women settled the islands in similar numbers.

Bjørn Myhre's "pagan reaction hypothesis" suggests that people moved around the North Atlantic coast a lot. He thinks that the spread of Christian missions caused or worsened ethnic tensions, leading to Viking expansion. There is some proof of such movement, like Irish missionaries in Iceland and the Faroe Islands in the 700s. But there isn't enough clear evidence.

The fourth idea is the Laithlind or Lochlann hypothesis. This word appears in old Irish writings. It usually means Norway, but some think it refers to Norse-controlled parts of Scotland. Donnchadh Ó Corráin believes that a large part of Scotland (the Northern and Western Isles and much of the coast) was taken by Vikings in the early 800s. He thinks a Viking kingdom was set up there earlier than the mid-800s. This is like a version of the earldom hypothesis. There is little archaeological proof for it. But it is clear that Vikings attacked the Irish coasts with support from some kind of base in the Hebrides. The exact date when this base became important is not certain. As Ó Corráin admits, "when and how the Vikings conquered and occupied the Isles is unknown, perhaps unknowable."

Early Viking Attacks

Norse people were in contact with Scotland before the first written records in the 700s. But we don't know how often or what kind of contact it was. Digs at Norwick in Shetland show that Scandinavian settlers arrived there as early as the mid-600s. This matches dates from Viking levels at Old Scatness.

From 793 onwards, Vikings repeatedly raided the British Isles. "All the islands of Britain" were destroyed in 794. Iona was attacked in 802 and 806. (These attacks on Christian settlements were not new. In the 500s, Picts raided Tiree. Tory Island was attacked in the early 600s. Donnán of Eigg and 52 friends were killed by Picts on Eigg in 617.)

Several Viking leaders, likely based in Scotland, appear in Irish records. These include Soxulfr in 837, Turges in 845, and Hákon in 847. The king of Fortriu, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the king of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, died in a big defeat to the Vikings in 839. Another early record mentions a king of "Viking Scotland" whose heir, Thórir, brought an army to Ireland in 848. Caittil Find was a leader of the Gallgáedil fighting in Ireland in 857.

The Frankish Annales Bertiniani might record the Viking conquest of the Inner Hebrides in 847. Amlaíb Conung, who died in 874, is called the "son of the king of Lochlainn" in the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland. This also suggests an early organized kingdom of Viking Scotland. In the same source, Amlaíb is said to have helped his father Gofraidh, who was being attacked by Vikings in Lochlainn around 872. Gofraidh died in 873 and might have been followed by his son Ímar, who also died that year. A sad poem for Áed mac Cináeda, a Pictish king who died in 878, suggests Kintyre might have been lost to his kingdom then. The Isle of Man might also have been taken by the Norse in 877 and was definitely held by them by 900.

Viking Regions in Scotland

The Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland

Before the Norse arrived, the Northern Isles were "Pictish in culture and speech." Although Orkney was "destroyed" by King Bridei in 682, it's unlikely Pictish kings had much ongoing control there.

According to the Orkneyinga Saga, around 872, Harald Fairhair became King of a united Norway. Many of his enemies fled to the islands of Scotland. Harald chased them and added the Northern Isles to his kingdom in 875. Then, about ten years later, he took the Hebrides too. The next year, the local Viking chiefs of the Hebrides rebelled. Harald sent Ketill Flatnose to stop them. Ketill did this quickly but then declared himself an independent "King of the Isles." He kept this title for the rest of his life. Hunter (2000) says Ketill was "in charge of an extensive island realm." This made him important enough to make deals with other princes. According to the Landnámabók, Ketill became ruler of an area already settled by Scandinavians. Some scholars think this whole story is made up. They believe it's based on later trips by Magnus Barelegs. For example, Woolf (2007) suggests it "looks very much like a story created in later days to legitimise Norwegian claims to sovereignty in the region." He thinks the earldom of Orkney was created in the early 1000s. Before that, local warlords fought for power with each other and with local farmers.

Still, Norse tradition says that Rognvald Eysteinsson received Orkney and Shetland from Harald as an earldom. This was to make up for his son's death in battle in Scotland. Rognvald then gave the earldom to his brother Sigurd the Mighty. Sigurd's family line almost died out. But Torf-Einarr, Rognvald's son by a slave, started a family line that controlled the Northern Isles for centuries after his death. His son Thorfinn Turf-Einarsson followed him. During this time, the Norwegian king Eric Bloodaxe, who had lost his throne, often used Orkney as a base for raids before he was killed in 954. Thorfinn's death and likely burial at the broch of Hoxa, on South Ronaldsay, led to a long period of family struggles. Whatever the exact history, it seems Orkney and Shetland were quickly becoming Norse in culture by this time.

The evidence from place names and language is very clear. There are very few place names in Orkney that come from Celtic languages. It's clear that Norn, a local version of Old Norse, was widely spoken by the people there for a long time. Norn was also spoken in Shetland. There is almost no evidence of Pictish elements in place names there, except for the three island names of Fetlar, Unst, and Yell.

Jarlshof in Shetland has the most complete remains of a Viking site in Britain. It's believed the Norse lived there continuously from the 800s to the 1300s. Among the many important finds are drawings scratched on slate of dragon-prowed ships. There is also a bronze-gilt harness piece made in Ireland in the 700s or 800s. Brough of Birsay in Orkney is another important archaeological site. Like Jarlshof, it shows continuous settlement from the Pictish to the Norse periods. There is also a remarkable collection of 12th-century runic writings inside Maeshowe.

Caithness and Sutherland: Mainland Norse Lands

In early Irish writings, Shetland is called Inse Catt—"the Isles of Cats." This might have been the name the pre-Norse people used for these islands. The Cat tribe definitely lived in parts of northern mainland Scotland. Their name can be found in Caithness and in the Gaelic name for Sutherland (Cataibh, meaning "among the Cats"). There is some limited evidence that Caithness might have been controlled by Gaelic speakers for a short time between the Pictish era and the Norse takeover. But if so, it was likely very brief.

Sigurd Eysteinsson and Thorstein the Red moved into northern Scotland. They conquered large areas in the late 800s. The sagas describe these areas as including all of Caithness and Sutherland, and possibly parts of Ross and even Moray. The Orkneyinga Saga tells how Sigurd defeated the Pict Máel Brigte Tusk. But Sigurd died from a strange injury after the battle.

Thorfinn Torf-Einarsson married into a local noble family. His son, Skuli Thorfinnsson, is recorded as asking the King of Scots for help in the 900s to claim his right as mormaer of Caithness. The Njáls saga says that Sigurd the Stout ruled "Ross and Moray, Sutherland and the Dales" of Caithness. It's possible that in the late 900s, the Scottish kings were allied with the Earl of Orkney against the Mormaer of Moray.

Thorfinn Sigurdsson expanded his father's lands south beyond Sutherland. By the 1000s, the Norwegian crown accepted that the earls of Orkney held Caithness as a fiefdom from the Kings of Scotland. But its Norse character remained throughout the 1200s. Raghnall mac Gofraidh was given Caithness after helping the Scottish king in a fight with Harald Maddadson, an earl of Orkney, in the early 1200s. This shared earldom ended after 1375. The Pentland Firth then became the border between Scotland and Norway.

No Norse place names have been found on the northern Scottish mainland south of Beauly. So far, no archaeological evidence of Norse activity has been found in the northwest mainland.

The Southern Isles: Suðreyjar

Like the Northern Isles, the Outer Hebrides and the northern Inner Hebrides were mostly Pictish in the early 800s. In contrast, the southern Inner Hebrides were part of the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata.

Almost all old names in the Outer Hebrides and in Coll, Tiree, and Islay (Inner Hebrides) were replaced by Norse names. There is little similarity between Pictish pottery in the north and Viking Age pottery. The similarities that do exist suggest the later pots might have been made by Norse people who had settled in Ireland, or by Irish slaves. Early Icelandic history often mentions slaves from Ireland and the Hebrides, but none from Orkney. Gaelic definitely continued to be spoken in the southern Hebrides during the settlement period. But place name evidence suggests it had a lower status. Norse might have been spoken in the Outer Hebrides until the 1500s.

There is no evidence of direct Norwegian rule in the area, except for a few short occupations. The written records are weak, and no contemporary records from the Norse period in the Outer Hebrides exist. However, it is known that the Hebrides were taxed using the Ounceland system. Evidence from Bornais suggests that settlers there might have been richer than similar families in the Northern Isles. This could be because of a more relaxed political system. Later, the Hebrides sent eight representatives from Lewis and Harris and Skye, and another eight from the southern Hebrides, to the Tynwald parliament on Man.

Colonsay and Oronsay have important pagan Norse burial grounds. An 11th-century cross slab decorated with Irish and Ringerike Viking art was found on Islay in 1838. Rubha an Dùnain, an uninhabited peninsula south of the Cuillin hills on Skye, has a small loch called Loch na h-Airde. This loch is connected to the sea by a short artificial canal. This loch was an important place for sea activity for many centuries, from the Viking period to later Scottish clan rule. There is a stone quay and a system to keep water levels constant. Boat timbers found there have been dated to the 1100s. Only three rune stones are known from the west coast of Scotland. They are on Christian memorials found on Barra, Inchmarnock, and Iona.

In the Firth of Clyde, Norse burials have been found on Arran, but not Bute. Place name evidence suggests that settlement there was much less developed than in the Hebrides. On the mainland coast, there are many Norse place names around Largs. An ornate silver brooch was found on a hillside near Hunterston. It is likely from 7th-century Ireland but has a 10th-century runic inscription. Five Hogback monuments found in Govan suggest Scandinavian groups lived inland.

The Isle of Man (which was part of Scotland from 1266 until the 1300s) was controlled by the Norse–Gaels early on. From 1079 onwards, the Crovan dynasty ruled. This is shown by the Chronicles of Mann and by the many Manx runestones and Norse place names. The modern-day Diocese of Sodor and Man keeps the old name.

Western Coast: Norse Influence

South of Sutherland, there are many place names showing Norse settlement along the entire western coast. However, unlike on the islands, settlement in the south seems to have been shorter. It also happened alongside existing settlements rather than replacing them completely. The difference between the Innse Gall (islands of the foreigners) and the Airer Goidel (coastland of the Gael) also suggests a difference between island and mainland early on. In Wester Ross, most Gaelic names on the coast today are likely from the Medieval period, not pre-Norse times. A lost document mentions the mainland village of Glenelg, opposite Skye, as being owned by the king of Man. As in Orkney and Shetland, Pictish seems to have been completely replaced wherever the Norse settled.

In the 800s, the first mentions of the Gallgáedil (meaning "foreign Gaels") appear. This term was used in later centuries for people of mixed Scandinavian-Celtic background or culture. They became powerful in west and southwest Scotland, parts of northern England, and the islands. This alliance between the two cultures, which also happened in Ireland, might have helped save the Gaels of Dál Riata from the same fate as the Picts in the north and west. Evidence for Norse settlement in mainland Argyll is limited. However, the Port an Eilean Mhòir ship burial in Ardnamurchan is the first boat-burial site found on the mainland of Britain.

South-West Scotland: Mixed Cultures

By the mid-900s, Amlaíb Cuarán controlled the Rhinns. The region gets its modern name of Galloway from the mix of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlers who created the Gall-Gaidel. Magnus Barelegs is said to have "subdued the people of Galloway" in the 1000s. Whithorn seems to have been a center for Hiberno-Norse craftspeople who traded around the Irish Sea by the end of the 900s. However, the evidence from place names, writings, and archaeology for widespread Norse (as opposed to Norse–Gael) settlement in the area is not strong.

The ounceland system (a way of taxing land) seems to have spread down the west coast, including much of Argyll. This was also true for most of the southwest, except for land next to the inner Solway Firth. In Dumfries and Galloway, the place name evidence is complex. It shows a mix of Gaelic, Norse, and Danish influence. The Danish influence likely came from contact with the large Danish holdings in northern England. One feature of the area is the number of names with a "kirk" prefix followed by a saint's name, like Kirkoswald. The meaning of this is not certain, but it also suggests a mixed Gaelic/Norse population.

Eastern Scotland: Limited Norse Presence

There is no evidence of permanent Viking settlement on the east coast south of the Moray Firth. There are also no Norse burials. However, raids and even invasions certainly happened. Dunnottar was taken during the reign of Domnall mac Causantín. The Orkneyinga saga records an attack on the Isle of May by Sweyn Asleifsson and Margad Grimsson:

- They sailed south off Scotland until they came to Máeyar. There was a monastery, the head of which was an abbot, by name, Baldwin. Swein and his men were detained there seven nights by stress of bad weather. They said they had been sent by Earl Rögnvald to the King of Scots. The monks suspected their tale, and thinking they were pirates, sent to the mainland for men. When Swein and his comrades became aware of this, they went hastily aboard their ship, after having plundered much treasure from the monastery.

Place name evidence of Scandinavian settlement is very limited on the east coast. In the southeast, Anglian was the main influence during this period.

Viking Politics and Rule

How Viking Leaders Ruled

The first stage of Norse expansion involved war bands looking for treasure and creating new settlements. The second stage involved these settlers becoming part of organized political groups. The most important of these early groups were the earls of Orkney in the north and the Uí Ímair in the south.

Even if the exact start of a formal earldom of Orkney is debated, the system continued steadily after that. Until the mid- to late 1000s, the earls of Orkney and kings of the Western Isles were likely independent rulers. Direct Norwegian rule began at the end of this century, ending this independence in the north. Unusually, from about 1100 onwards, the Norse jarls (earls) of the Northern Isles owed loyalty to Norway for Orkney. They also owed loyalty to the Scottish crown for their lands as earls of Caithness. In 1231, the line of Norse earls, which had been unbroken since Rognvald Eysteinsson, ended with Jon Haraldsson's murder in Thurso. The Earldom of Caithness was given to Magnus, the second son of the Earl of Angus. King Haakon IV of Norway confirmed Magnus as Earl of Orkney in 1236. In 1379, the earldom passed to the Sinclair family. They were also barons of Roslin near Edinburgh. But Orkney and Shetland remained part of Norway for another century.

The situation in the Suðreyar was more complicated. Different kings might have ruled over very different areas. Few of them seemed to have close control over this "far-flung sea kingdom." The Uí Ímair were certainly a powerful group from the late 800s to the early 1000s. Leaders like Amlaíb Cuarán and Gofraid mac Arailt claimed to be kings of the Isles. Norse sources also list various rulers like jarls Gilli, Sigurd the Stout, Håkon Eiriksson, and Thorfinn the Mighty as rulers over the Hebrides. They were vassals (loyal to) the Kings of Norway or Denmark. The dates from Irish and Norse sources don't overlap much. It's unclear if these are records of competing empires, or if they show Uí Ímar influence in the south and direct Norse rule in the north, or both. Also, two records in the Annals of Innisfallen might suggest that the Western Isles were not "organized into a kingdom or earldom" at this time. Instead, they might have been "ruled by groups of free landowners who regularly chose lawmen to lead their public affairs." The Annals of the Four Masters entries for 962 and 974 hint at a similar setup. Crawford (1987) suggests that influence from the south, rather than the north, was "usually strongest." But he also admits that the islands probably formed "groups of more or less independent communities."

Godred Crovan became the ruler of Dublin and Mann from 1079. From the early 1100s, the Crovan family became strong. They ruled as "Kings of Mann and the Isles" for the next 50 years. The kingdom then split because of Somerled. His sons inherited the southern Hebrides, while the Manx rulers kept the "north isles" for another century. The origins of both Godred Crovan and Somerled are unclear. Godred might have been an Uí Ímair leader from Islay. Somerled married a Crovan heiress.

So, it's clear that even with different groups fighting for power, the Hebrides and islands of the Clyde were mostly controlled by rulers of Scandinavian origin from "at least the late tenth century." This lasted until the kingdom of Scotland grew and expanded into the west in the 1200s.

Viking Impact on Pictland, Strathclyde, and Alba

The early Viking threats might have sped up a long process of making the Pictish kingdoms more Gaelic. They adopted Gaelic language and customs. The Gaelic and Pictish crowns merged. Historians still debate if it was a Pictish takeover of Dál Riata, or the other way around. This led to the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín in the 840s. He brought to power the House of Alpin, who led a combined Gaelic–Pictish kingdom for almost 200 years.

In 870, Dumbarton was attacked by Amlaíb Conung and Ímar, "the two kings of the Northmen." They "returned to Dublin from Britain" the next year with many captives. Dumbarton was the capital of the Kingdom of Strathclyde. This was a major attack that might have brought all of mainland Scotland under temporary Ui Imair control. Three years earlier, Vikings had taken Northumbria, forming the Kingdom of York. They later conquered much of England except for a smaller Kingdom of Wessex. This left the new combined Pictish and Gaelic kingdom almost surrounded. Amlaíb and his brother Auisle "destroyed all of Pictland and took their hostages." They later occupied this land for a long time. The 875 Battle of Dollar was another big defeat for the Picts/Scots.

In 902, the Norse suffered a big loss in Ireland, losing control of Dublin. This seems to have made their attacks on the growing kingdom of Alba stronger. A year later, Dunkeld was attacked. Ímar, the "grandson of Ímar," was killed in battle with the forces of Constantine II in mainland Scotland. In the late 900s, Alban forces won the battle of "Innisibsolian" against Vikings. Yet, these events were setbacks for the Norse, not a final defeat. More important were their defeats at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937 and at the Battle of Tara in 980.

In 962, Ildulb mac Causantín, King of Scots, was killed (according to the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba) fighting the Norse near Cullen, at the Battle of Bauds. But the line of the House of Alpin stayed strong. The threat from the Scandinavian presence to the growing Kingdom of Scotland lessened. Perhaps to fight growing Irish influence in the Western Isles, Magnus Barelegs brought them back under direct Norwegian rule by 1098. He first took Orkney, the northern Scottish mainland, and the Hebrides. There, he "dyed his sword red in blood" in the Uists. In that year, Edgar of Scotland signed a treaty with Magnus. This treaty set much of the boundary between Scottish and Norwegian claims in the islands. Edgar formally accepted the situation by giving up his claims to the Hebrides and Kintyre.

After Somerled's actions and his death at the Battle of Renfrew, the Kings of the Isles became weaker compared to the Scottish state. But more than 150 years later, Norway intervened again, this time without success. After Haakon Haakonarson's failed invasion and the undecided Battle of Largs, the Hebrides and Mann, and all rights the Norwegian crown "had of old therein," were given to the Kingdom of Scotland. This was a result of the 1266 Treaty of Perth.

In 1468, Orkney was pledged by Christian I, as king of Norway. This was security for the payment of the dowry of his daughter Margaret, who was engaged to James III of Scotland. Since the money was never paid, the connection with the Scottish crown became permanent.

Viking Religion, Culture, and Economy

There is evidence of different burial customs among Norse settlers in Scotland. For example, grave goods were found on Colonsay and Westray. But there is little to confirm that Norse gods were worshipped before Christianity returned. The Odin Stone has been seen as proof of Odinic beliefs. However, its name might just mean "oathing stone." A few Scandinavian poems suggest that people in Orkney understood parts of the Norse pantheon. But this isn't strong proof of active beliefs. Still, it's likely that pagan practices existed in early Scandinavian Scotland.

According to the sagas, the Northern Isles became Christian in 995. This happened when Olav Tryggvasson stopped at South Walls on his way from Ireland to Norway. The King called the jarl Sigurd the Stout and said, "I order you and all your subjects to be baptised. If you refuse, I'll have you killed on the spot and I swear I will ravage every island with fire and steel." Not surprisingly, Sigurd agreed. The islands became Christian quickly. They received their own bishop, Henry of Lund (also known as "the Fat"), who was appointed before 1035.

The biggest source of Scottish influence after the Scottish earls were appointed in the 1200s was probably through the church. However, Scottish influence on the culture of Orkney and Shetland was quite limited until the late 1300s or later. A wave of Scottish business people helped create a diverse and independent community. This included farmers, fishermen, and merchants who called themselves Communitas Orchadensis. They became increasingly able to defend their rights against their feudal overlords, whether Norwegian or Scots. This independent spirit might have been encouraged by Norwegian government, which was more communal and federal compared to Scotland. It wasn't until the mid-1500s that Norse systems were replaced by Scottish ones. This followed large-scale immigration from the south. The islanders were probably bilingual until the 1600s.

Again, the situation in the Hebrides is much less clear. There was a Bishop of Iona until the late 900s. Then there is a gap of over a century, possibly filled by the Bishops of Orkney. The first Bishop of Mann was appointed in 1079. The conversion of Scandinavian Scotland to Christianity was a big event. It ended slavery and brought Viking society into the main European culture. This happened early on. But the popular image of wild berserkers and the Norse as "enemies of social progress" remains. This is despite much evidence that in their later period, Norse-speaking people were "enlightened practitioners of maritime commercial principles."

Þings were open-air government meetings. They met with the jarl present. These meetings were open to almost all free men. At these sessions, decisions were made, laws were passed, and complaints were judged. Examples include Tingwall and Law Ting Holm in Shetland, Dingwall in Easter Ross, and Tynwald on the Isle of Man.

Women had a relatively high status during the Viking Age. This might be because people moved around a lot. We know little about their role in the Scandinavian colonies of Scotland. But indirect evidence from graves during pagan and Christian times suggests roles similar to those elsewhere. Some well-known figures include Gormflaith ingen Murchada, Gunnhild Gormsdóttir, Aud the Deep-Minded, and Ingibjörg. Ingibjörg was the daughter of Earl Hakon Paulsson and wife of King Olaf Godredsson.

The Norse legacy of art and architecture is limited. The Christchurch at Brough of Birsay, now in ruins, was an early seat of the Bishops of Orkney. St. Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall is a unique example of Norse-era building in Scotland. St. Magnus Church, on Egilsay, still has its round tower. The famous Lewis chessmen are the best-known treasure trove. Many grave goods have been found, including brooches and weapons like those from the Scar boat burial.

There is growing evidence of how important trade and business were. Data from the Outer Hebrides suggests that pigs were more important in Viking farming than before. Red deer numbers might have been controlled, not just hunted. Herring fishing became an important business. Trade with southern centers like Dublin and Bristol might have been important. Coins found at Bornais and Cille Pheadair were made in Norway, Westphalia, and England, but none from Scotland. Ivory from Greenland was also found there.

Viking Influence Today

Norse and Viking settlements have left a mark on the edges of Scotland. We can see this in place names, language, genetics, and other parts of cultural heritage.

Scandinavian influence in Scotland was probably strongest in the mid-1000s. This was during the time of Thorfinn Sigurdsson. He tried to create one political and religious area stretching from Shetland to Man. The Suðreyjar have a total land area of about 8374 square kilometers. Caithness and Sutherland have a combined area of 7051 square kilometers. So, the permanent Scandinavian lands in Scotland at that time must have been at least a fifth to a quarter of modern Scotland's land area.

The Viking invasions might have accidentally helped create modern Scotland. Their destructive raids first weakened Pictland, Strathclyde, and Dál Riata. But these "harassed remnants" eventually formed a united front. So, Norse aggression played a big role in creating the kingdom of Alba. This was the core from which the Scottish kingdom grew as Viking influence faded. It was similar to how Wessex grew to become the kingdom of England in the south.

Some Scots are proud of their Scandinavian ancestors. For example, Clan MacLeod of Lewis says it comes from Leod. Tradition says Leod was a younger son of Olaf the Black. Clan MacNeacail of Skye also claims Norse ancestry. Sometimes, people talk about Scotland joining "the Nordic circle of nations" in modern political discussions.

However, unlike the Danelaw in England, the Scandinavian occupation of Scotland doesn't have one common name. This might be because the different invasions are not as well documented. It also suggests that people don't widely understand this history. Compared to the Roman occupations of Scotland, the Norse kingdoms lasted much longer. They were also more recent and had a much bigger impact on spoken language and, by extension, culture and lifestyles. But they were limited to areas that are quite far from today's main population centers. Also, no matter the actual impact of Scandinavian culture, the traditional leaders of the Scottish nation generally came from Pictish and Gaelic families. So, Vikings are often seen in a negative way, as a foreign invasion, rather than a key part of a multi-cultural society.

Still, in the Northern Isles, the Scandinavian connection is celebrated. One of the most famous events is the Lerwick fire-festival Up Helly Aa. Shetland's connection with Norway has been especially strong. When Norway became independent again in 1905, the Shetland authorities sent a letter to King Haakon VII. They wrote: "Today no 'foreign' flag is more familiar or more welcome in our voes and havens than that of Norway, and Shetlanders continue to look upon Norway as their mother-land, and recall with pride and affection the time when their forefathers were under the rule of the Kings of Norway." At the 2013 Viking Congress in Shetland, the Scottish Government announced plans to strengthen Scotland’s historical links with Scandinavia.

Canadian scholar Michael Stachura wrote about Scottish literature's focus on "northness" in his PhD paper. He included a chapter on Orkney writer George Mackay Brown and how he used Orkney’s Norse past in his stories.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |