Scotland during the Roman Empire facts for kids

This article is about the time when the Roman Empire had contact with the land we now call Scotland. Even though the Romans tried to conquer and rule parts of it between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, most of modern Scotland was never fully part of their empire. The people living there, like the Caledonians and the Maeatae, kept their independence.

During the Roman period, the island of Great Britain north of the River Forth was known as Caledonia. The whole island was called Britannia, which was also the name for the Roman province that covered most of modern England and Wales. Roman soldiers first arrived in what is now Scotland around 71 AD. They had spent the previous 30 years conquering the Celtic Britons in southern Great Britain. Roman armies, led by generals like Quintus Petillius Cerialis and Gnaeus Julius Agricola, fought against the Caledonians in the 70s and 80s AD. A book called Agricola, written by the Roman governor's son-in-law Tacitus, mentions a Roman victory at a place called "Mons Graupius". This battle gave its name to the Grampian Mountains, but historians still debate where it actually happened.

Agricola later sailed around the island, just like the Greek explorer Pytheas had done before. He received promises of loyalty from local tribes. He first set up a border of control along the Gask Ridge. Later, the Romans moved their border south to a line from the Solway Firth to the River Tyne. This border was later strengthened with a large wall called Hadrian's Wall. Several Roman commanders tried to conquer the lands north of this wall. In the 2nd century, they expanded north again and built another fortified wall, the Antonine Wall.

The history of this time is complicated and not many records survived. For example, the Roman area called Valentia might have been the land between the two Roman walls, or the area around Hadrian's Wall, or even Roman Wales. The Romans only held most of their territory in Caledonia for a little over 40 years. They probably only controlled any Scottish land for about 80 years in total. Some Scottish historians, like Alistair Moffat, believe that the Roman influence was not very important. It is now thought that the Romans never controlled even half of present-day Scotland. Roman armies stopped having a big impact on the area after about 211 AD.

The ideas of "Scots" and "Scotland" as a unified country did not appear until many centuries later. However, the Roman Empire did influence parts of Scotland. By the time Roman rule ended in Britain around 410 AD, the different Iron Age tribes in the area had either united or come under the control of the Picts. The southern part of the country was taken over by tribes of Romanized Britons. The Scots (Gaelic Irish raiders) who would later give Scotland its English name, began to settle along the west coast. All three groups might have been involved in the Great Conspiracy, a large attack that overwhelmed Roman Britain in 367 AD. This era also saw the first written accounts of the native people. The most lasting things Rome left behind, however, were Christianity and the ability to read and write. Both arrived indirectly through Irish missionaries.

Contents

- Early Scottish History in Writing

- Iron Age Life in Scotland

- The Roman Invasion of Caledonia

- The Battle of Mons Graupius

- Settlements and Southern Brochs

- Hadrian's Wall: The Great Barrier

- The Antonine Wall: A New Push North

- The 3rd Century: More Roman Invasions

- The Rise of the Picts

- Modern Discoveries and Studies

- Rome's Lasting Impact on Scotland

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Scottish History in Writing

People had lived in Scotland for thousands of years before the Romans arrived. But it was during the time of the Greeks and Romans that Scotland was first written about.

The book On the Cosmos, possibly by Aristotle, mentions two "very large" islands called Albion (Great Britain) and Ierne (Ireland). The Greek explorer and geographer Pytheas visited Britain sometime between 322 and 285 BC. He might have sailed all the way around the mainland, which he described as being shaped like a triangle. In his book On the Ocean, he called the most northern point Orcas (Orkney).

The first written record of a formal link between Rome and Scotland is when the "King of Orkney" was one of 11 British kings who surrendered to Emperor Claudius at Colchester in 43 AD. This happened after the Romans invaded southern Britain three months earlier. The long distance and short time involved suggest that Rome and Orkney had a connection before this. However, no proof of this has been found. This is very different from how the Caledonians later resisted Rome. Copies of Pytheas's On the Ocean existed in the 1st century AD. This means Roman military leaders would have had some basic knowledge of northern Britain's geography. Pomponius Mela, a Roman geographer, wrote in his book De Chorographia around 43 AD that there were 30 Orkney islands and seven Haemodae (possibly Shetland). Pottery found at the broch of Gurness shows that Orkney had connections with Rome before 60 AD.

By the time of Pliny the Elder (who died in 79 AD), Roman knowledge of Scotland's geography had grown. They knew about the Hebudes (Hebrides), Dumna (probably the Outer Hebrides), the Caledonian Forest, and the Caledonians.

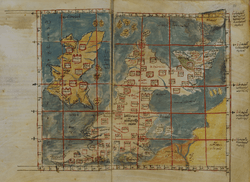

Ptolemy, possibly using older information and newer accounts from Agricola's invasion, listed 18 tribes in Scotland in his Geography. Many of these names are not clear today. His information for the north and west is less reliable. This suggests that early Roman knowledge of these areas came mostly from observations made from the sea. Interestingly, his maps show most of Scotland north of Hadrian's Wall bent at a right angle, stretching east from the rest of Britain.

Iron Age Life in Scotland

The Iron Age was a time when people used iron tools. In Scotland, this period lasted for a long time. Ptolemy's map shows tribes living north of the Forth-Clyde area. These included the Cornovii in Caithness, and others like the Caereni, Smertae, Carnonacae, Decantae, Lugi, and Creones north of the Great Glen. The Taexali lived in the north-east, the Epidii in Argyll, the Venicones in Fife, the Caledonians in the central Scottish Highlands, and the Vacomagi near Strathmore. It is likely that all these groups spoke a form of Celtic language called Pritennic. The people in southern Scotland were the Damnonii in the Clyde valley, the Novantae in Galloway, the Selgovae on the south coast, and the Votadini to the east. These groups may have spoken a different form of Celtic language called Brythonic.

We have found hundreds of Iron Age sites in Scotland. However, there is still much to learn about how the Celts lived during this early Christian era. It is hard to accurately date things from this period using radiocarbon dating, so we don't fully understand the timeline. Most archaeological work in Scotland has focused on the western and northern islands. Less work has been done on the mainland, so our understanding of mainland societies is more limited.

People in early Iron Age Scotland, especially in the north and west, lived in large stone buildings called Atlantic roundhouses. Hundreds of these houses still exist today. Some are just piles of stones, while others have impressive towers and other buildings. They were built from about 800 BC to 300 AD, with the biggest ones made around 200 BC. The most massive buildings from this time are the circular broch towers. Most broch ruins are only a few metres high, but five still stand over 6.5 metres (21 feet) tall. There are at least 100 broch sites in Scotland. Despite much research, we still debate their purpose and what kind of societies built them.

In some parts of Iron Age Scotland, there doesn't seem to have been a strict social ladder with rich and poor, which is very unusual for most of history. Studies show that these stone roundhouses, with their very thick walls, must have housed almost everyone on islands like Barra and North Uist. Iron Age settlement patterns in Scotland were not the same everywhere. But in these places, there is no sign of a special class living in big castles or forts. There were no elite priests or peasants who couldn't get the same kind of housing as others.

Over 400 souterrains have been found in Scotland, many in the south-east. These are small underground structures. Few have been accurately dated, but those that have suggest they were built in the 2nd or 3rd centuries AD. Their purpose is also a mystery. They are usually found near settlements (whose wooden houses have not survived as well). They might have been used to store food that could spoil easily.

Scotland also has many vitrified forts, which are stone forts whose walls have been partly melted by fire. It's hard to date these accurately. Studies of a fort at Finavon Hill near Forfar in Angus suggest it was destroyed either in the last two centuries BC or in the mid-1st millennium AD. The lack of Roman objects (which are common in nearby souterrain sites) suggests that many of these forts were abandoned before the Romans arrived.

Unlike the earlier Neolithic and Bronze Ages, which left huge monuments for the dead, Iron Age burial sites in Scotland are rare. A recent discovery at Dunbar might help us understand this period better. A similar site with a warrior's grave at Alloa has been dated to 90–130 AD. A traveler named Demetrius of Tarsus told the writer Plutarch about a trip to the west coast around 83 AD. He said it was "a gloomy journey amongst uninhabited islands" but that he had visited one island where holy men lived. He did not mention druids or the name of the island.

The Roman Invasion of Caledonia

The friendly start recorded at Colchester did not last. We don't know much about the plans of the leaders in mainland Scotland in the 1st century AD. But by 71 AD, the Roman governor Quintus Petillius Cerialis had started an invasion. The Votadini, who lived in south-east Scotland, came under Roman control early on. Cerialis sent one army division north through their land to the Firth of Forth. The XXth Legion took a western route through Annandale to try and surround the Selgovae, who lived in the central Southern Uplands. Early success encouraged Cerialis to go further north. He began building a line of forts, called Glenblocker forts, north and west of the Gask Ridge. This line marked a border between the Venicones to the south and the Caledonians to the north.

In the summer of 78 AD, Gnaeus Julius Agricola arrived in Britain as the new governor. Two years later, his armies built a large Roman fort at Trimontium near Melrose. Digs in the 20th century found important things there. These included the foundations of several buildings built one after another, Roman coins, and pottery. Roman army items were also found, such as a collection of Roman armour (including fancy cavalry parade helmets) and horse fittings (with bronze saddle plates and studded leather face coverings). Agricola is said to have pushed his armies to the mouth of the "River Taus" (usually thought to be the River Tay). He built forts there, including a large army base at Inchtuthil.

The Battle of Mons Graupius

In the summer of 84 AD, the Romans fought the large armies of the Caledonians at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Agricola's forces included a fleet of ships. He arrived at the battle site with light infantry and British auxiliary troops (soldiers from conquered lands). It is thought that about 20,000 Romans faced 30,000 Caledonian warriors.

Agricola put his auxiliary troops in the front line, keeping the main Roman legions in reserve. He wanted to fight hand-to-hand to make the Caledonians' long, slashing swords useless. Even though the Caledonians were defeated and lost the battle, two-thirds of their army managed to escape. They hid in the Scottish Highlands or the "trackless wilds" as Tacitus called them. Tacitus estimated that about 10,000 Caledonians died, and roughly 360 Romans. Many writers believe the battle happened in the Grampian Mounth, where the North Sea could be seen. Some suggest the battle site might have been Kempstone Hill, Megray Hill, or other hills near the Raedykes Roman camp. These high points are close to the Elsick Mounth, an old trackway used by Romans and Caledonians for military movements. Other ideas include the hill of Bennachie in Aberdeenshire, the Gask Ridge near Perth, and Sutherland. Some have even suggested that because there's no archaeological proof and Tacitus reported very few Roman deaths, the battle might have been made up.

Calgacus, the Caledonian Leader

The first person from Scotland to be known by name in history was Calgacus ("the Swordsman"). He was a leader of the Caledonians at Mons Graupius. Tacitus, in his book Agricola, describes him as "the most distinguished for birth and valour among the chieftains". Tacitus even created a speech for Calgacus before the battle, in which he described the Romans:

Robbers of the world, having by their universal plunder exhausted the land, they rifle the deep. If the enemy be rich, they are rapacious; if he be poor, they lust for dominion; neither the east nor the west has been able to satisfy them. Alone among men they covet with equal eagerness poverty and riches. To robbery, slaughter, plunder, they give the lying name of empire; they make a solitude and call it peace.

What Happened After the Battle

We don't know what happened to Calgacus. But according to Tacitus, after the battle, Agricola ordered the commander of his fleet to sail around the north of Scotland. This was to confirm that Britain was an island and to receive the surrender of the Orcadians. It was announced that Agricola had finally brought all the tribes of Britain under control. However, the Roman historian Cassius Dio reports that this sailing trip led to Emperor Titus being praised for the 15th time in 79 AD. This is five years before most historians believe Mons Graupius took place.

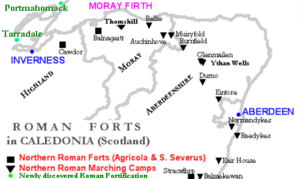

Temporary army camps might have been built along the southern shores of the Moray Firth, but their existence is still debated. The total number of Roman soldiers in Scotland during the Flavian period (when the Flavians ruled) is thought to have been about 25,000 troops. These soldiers would have needed 16–19,000 tons of grain each year. Also, a lot of material was needed to build the forts. It's estimated that 1 million cubic feet (28,315 cubic metres) of timber was used in the 1st century. Ten tons of buried nails were found at the Inchtuthil site. This fort might have held up to 6,000 men. Just its walls would have used 30 kilometres of wood, which would have cleared 100 hectares (247 acres) of forest.

Soon after announcing his victory, Agricola was called back to Rome by Emperor Domitian. His job was given to Sallustius Lucullus. Agricola's successors seemed unable or unwilling to conquer the far north further. Despite his successes, Agricola himself lost favor. It's possible that Domitian was told that Agricola's claims of a great victory were not entirely true. The fortress at Inchtuthil was taken apart before it was even finished. Other forts on the Gask Ridge (built to strengthen Roman control in Scotland after Mons Graupius) were abandoned within a few years. It's possible that the cost of a long war was too high compared to any benefits. So, it was decided to leave the Caledonians alone. By 87 AD, Roman control was limited to the Southern Uplands. By the end of the 1st century, the northern border of Roman expansion was a line between the River Tyne and Solway Firth. The Elginhaugh fort in Midlothian dates from this period. Castle Greg in West Lothian might also be from this time, likely used to watch an east-west road along the Pentlands, from the River Forth to the Clyde Valley.

Because of the Roman advance, various hill forts like Dun Mor in Perthshire, which had been left empty by the native people long ago, were re-occupied. Some new ones might even have been built in the north-east, like Hill O' Christ's Kirk in Aberdeenshire.

Settlements and Southern Brochs

Ptolemy's Geography lists 19 "towns" based on information gathered during Agricola's campaigns. No archaeological proof of any real towns has been found from this time. The names might have referred to hill forts or temporary places for markets and meetings. Most of the names are unclear. Devana might be modern Banchory. Alauna ("the rock") in the west is probably Dumbarton Rock, and the place with the same name in the east Lowlands might be the site of Edinburgh Castle. Lindon might be Balloch by Loch Lomond.

There are remains of various broch towers in southern Scotland that seem to be from just before or after Agricola's invasion. There are about fifteen of them, found in four areas: the Forth valley, near the Firth of Tay, the far south-west, and the eastern Borders. Their presence so far from the main areas where brochs were built is a bit of a mystery. The destruction of the Leckie broch might have been done by Roman invaders. Yet, like the nearby site of Fairy Knowe at Buchlyvie, a lot of both Roman and native objects have been found there. Both buildings were built in the late 1st century and were clearly important places. The people living there raised sheep, cattle, and pigs, and also hunted wild animals like Red deer and Wild boar.

Edin's Hall Broch in Berwickshire is the best-preserved southern broch. Although its ruins look a bit like some of the larger broch villages in Orkney, it's unlikely the tower was ever more than one story high. No Roman objects have been found at this site. Many ideas have been suggested for why these structures exist. They might have been built by northern invaders after the Romans left following Agricola's advance. Or, they might have been built by Roman allies who were encouraged to copy the impressive northern style to stop local resistance. Perhaps even the Orcadian chiefs, who had a good relationship with Rome, continued this. It's also possible that their construction had little to do with Roman border policy. It could simply have been a new style brought in by southern elites, or a way for these elites to show alliance with the free north against the growing Roman threat before the invasion.

Hadrian's Wall: The Great Barrier

Quintus Pompeius Falco was governor of Britannia between 118 and 122 AD. He is thought to have stopped a rebellion involving the Brigantes of northern Britain and the Selgovae. In his last year, he hosted a visit from Emperor Hadrian. This visit led to the building of Hadrian's Wall (in Latin, Rigore Valli Aeli, meaning "the line along Hadrian's frontier").

This wall became one of the strong borders (called limites) of the Roman Empire. It is a stone fortification built across what is now northern England. The wall was 80 Roman miles (73.5 modern miles or 117 kilometres) long. Its width and height depended on the building materials available nearby. East of the River Irthing, the wall was made of squared stone, 3 metres (9.7 feet) wide and 5–6 metres (16–20 feet) high. West of the river, it was first made of turf, 6 metres (20 feet) wide and 3.5 metres (11.5 feet) high, but was later rebuilt in stone. The wall was also strengthened with ditches, mounds, and forts.

The wall had several purposes. Defense was the most obvious. But it also controlled movement behind the line, allowed quick sharing of military information, and helped collect taxes on goods. Its huge size also showed Rome's power to its enemies and was meant to make its builder, Hadrian, look important. Hadrian's Wall remained the border between the Roman and Celtic worlds in Britain until 139 AD. It was briefly replaced by the Antonine Wall.

The Antonine Wall: A New Push North

Quintus Lollius Urbicus became governor of Roman Britain in 138 AD, appointed by the new Emperor Antoninus Pius. Urbicus was from Numidia (modern Algeria). Before coming to Britain, he fought in the Jewish Rebellion from 132–135 AD, and then governed Germania Inferior.

Antoninus Pius soon changed the policy of his predecessor Hadrian. Urbicus was ordered to start conquering Lowland Scotland again by moving north. Between 139 and 140 AD, he rebuilt a fort at Corbridge. By 142 or 143 AD, special coins were made to celebrate a victory in Britain. This means Urbicus likely led the reoccupation of southern Scotland around 141 AD, probably using the 2nd Augustan Legion. He clearly fought against several British tribes (possibly including some of the northern Brigantes). He certainly fought against the lowland tribes of Scotland: the Votadini and Selgovae in the Scottish Borders, and the Damnonii of Strathclyde. His total army might have been about 16,500 men.

It seems Urbicus planned his attack from Corbridge. He advanced north, leaving forts at High Rochester in Northumberland and possibly at Trimontium. He then moved towards the Firth of Forth. After securing a land route for soldiers and supplies along Dere Street, Urbicus probably set up a supply port at Carriden for grain and other food. Then he moved against the Damnonii.

Success came quickly. The building of a new border (limes) between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde began. Soldiers from at least one British legion helped build this new turf barrier. This is shown by an inscription from the fort at Old Kilpatrick, which was the western end of the Antonine Wall. Today, the grass-covered wall is the remains of a defensive line made of turf about 7 metres (20 feet) high, with nineteen forts. It was built after 139 AD and stretched for 60 kilometres (37 miles). It's possible that after the defenses were finished, Urbicus turned his attention to the fourth lowland Scottish tribe, the Novantae, who lived in the Dumfries and Galloway area. The main lowland tribes, caught between Hadrian's Wall to the south and the new turf wall to the north, later formed a group against Roman rule, known as the Maeatae.

The Antonine Wall had several purposes. It provided a defensive line against the Caledonians. It cut off the Maeatae from their Caledonian allies and created a safe zone north of Hadrian's Wall. It also made it easier for troops to move between east and west. But its main purpose might not have been just military. It allowed Rome to control and tax trade. It might also have stopped new subjects, who might not be loyal to Rome, from talking to their independent relatives in the north and planning rebellions. Urbicus achieved impressive military successes, but like Agricola's, they did not last long. After taking twelve years to build, the wall was overrun and abandoned soon after 160 AD.

The destruction of some southern brochs might have happened during the Antonine advance. The idea is that whether or not they had been symbols of Roman support before, they were no longer useful from a Roman point of view.

The 3rd Century: More Roman Invasions

The Roman border became Hadrian's Wall again, but Roman attacks into Scotland continued. At first, forts in the south-west were still used, and Trimontium remained active. But these too were abandoned after the mid-180s.

Roman troops, however, went far into the north of modern Scotland several more times. In fact, there are more Roman marching camps in Scotland than anywhere else in Europe. This is because of at least four major attempts to conquer the area. The Antonine Wall was used again for a short time after 197 AD. The most important invasion was in 209 AD. Emperor Septimius Severus claimed he was provoked by the Maeatae's fighting. He campaigned against the Caledonian Confederacy. Severus invaded Caledonia with an army possibly over 40,000 strong.

According to Cassius Dio, Severus caused great destruction to the native people. He also lost 50,000 of his own men to the constant attacks of guerrilla tactics. However, these numbers are likely much too high.

A line of forts was built in the north-east. Some of these might be from the earlier Antonine campaign. These include camps linked to the Elsick Mounth, such as Normandykes, Ythan Wells, Deers Den, and Glenmailen. However, only two forts in Scotland, at Cramond and Carpow (in the Tay valley), are definitely known to have been used permanently during this invasion. The troops were pulled back to Hadrian's Wall around 213 AD. There is some evidence that these campaigns led to the complete destruction and abandonment of souterrains in southern Scotland. This might have been due to Roman military attacks or because local grain markets collapsed after the Romans left.

By 210 AD, Severus's campaign had made good progress. But his campaign was cut short when he became very ill and died at Eboracum in 211 AD. Although his son Caracalla continued fighting the next year, he soon made peace. The Romans never again campaigned deep into Caledonia. They soon withdrew permanently south to Hadrian's Wall.

During the talks to get a truce for the Roman retreat, the first recorded words from a native of Scotland were spoken. When Julia Domna, the wife of Septimius Severus, criticized the morals of the Caledonian women, the wife of Caledonian chief Argentocoxos replied: "We fulfill the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest".

Little is known about this group of Iron Age tribes. It might have included people who fled from Roman rule further south. The exact location of "Caledonia" is unknown, and its borders probably changed often. The name itself is Roman, used by Tacitus, Ptolemy, Pliny the Elder, and Lucan. But we don't know what the Caledonians called themselves. It's likely that before the Roman invasions, political power in the region was spread out. No evidence has been found of any specific Caledonian military or political leaders.

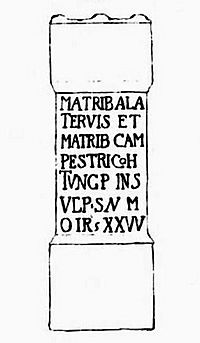

Later Roman trips into Scotland were usually limited to scouting in the area between the walls. They also involved trading, giving gifts to the native people to buy truces, and eventually the spread of Christianity. The Ravenna Cosmography, which uses a 3rd or 4th-century Roman map, identifies four loci (meeting places, possibly markets) in southern Scotland. Locus Maponi is possibly the modern Lochmabenstane near Gretna, which continued to be used as a meeting point for a long time. Two others show meeting places for the Damnonii and Selgovae. The fourth, Manavi, might be Clackmannan. From the time of Caracalla onwards, no more attempts were made to permanently control territory in Scotland.

The Rise of the Picts

The Roman presence in Scotland happened at the same time as the rise of the Picts. The Picts were a group of tribes who lived north of the Forth and Clyde from Roman times until the 10th century. They are often thought to be the descendants of the Caledonians, but there isn't strong proof for this. We also don't know what the Picts called themselves. People often say they tattooed themselves, but there's limited evidence for this. Pictures of Pictish nobles, hunters, and warriors, both male and female, on their monumental stones don't clearly show tattoos. The Gaels of Dalriada called the Picts Cruithne, and Irish poets described them as very similar to themselves.

We don't know how the Pictish tribes came together. But some think that reacting to the growing Roman Empire might have been a reason. The early history of Pictland is unclear. In later periods, there were many kings, each ruling separate kingdoms. One king, sometimes two, would usually be more powerful than their smaller neighbors. Old writings like De Situ Albanie, the Pictish Chronicle, and the Duan Albanach, along with Irish legends, suggest there were seven Pictish kingdoms. More might have existed, and some evidence suggests a Pictish kingdom also existed in Orkney.

The Picts' relationship with Rome seems to have been less openly hostile than that of their Caledonian ancestors, at least at first. There were no more big battles. Conflicts were usually limited to raiding parties from both sides of the border. This continued until just before and after the Roman retreat from Britain. Their success in keeping Roman forces back cannot be explained just by Caledonia being far away or the difficult land. It might partly be because it was hard to control people who didn't follow the local government rules that Roman power usually relied on.

The technology of daily life is not well recorded. But archaeological evidence shows it was similar to that in Ireland and Anglo-Saxon England. Recently, evidence of watermills has been found in Pictland. Kilns were used for drying wheat or barley grains, which was hard to do otherwise in the changing, mild climate. Although built earlier, brochs, roundhouses, and crannogs continued to be used into and beyond the Pictish period.

Elsewhere in Scotland, wheelhouses were built, probably for religious reasons, in the west and north. Their locations are very specific. This suggests they might have been within a certain political or cultural border. Whether their appearance and disappearance are linked to the period of Roman influence in Scotland is still debated. It's not known if the culture that built them was "Pictish" itself, but the Picts would certainly have known about them.

As Rome's power weakened, the Picts became bolder. War bands raided south of Hadrian's Wall in 342, 360, and 365 AD. They also took part with the Attacotti in the Great Conspiracy of 367 AD. Rome fought back. A campaign led by Count Theodosius in 369 AD re-established a province. It was renamed Valentia in honor of the emperor. Its location is unclear, but it is sometimes placed on or beyond Hadrian's Wall. Another campaign was launched in 384 AD. But both were short-lived successes. Rome fully withdrew from Britain by 410 AD, never to return.

Modern Discoveries and Studies

From the mid-1700s to the mid-1800s, a Charles Bertram created a fake book called Description of Britain (in Latin, De Situ Britanniæ). This fake book placed Valentia exactly between Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall. It even claimed Rome had a "short-lived" Roman province called Vespasiana beyond the Antonine Wall in lowland Scotland. We now know this book was one of the most successful historical fakes ever. It is no longer believed to contain any true, independent information.

In 1984, a possible Roman fort was found using aerial photography at Easter Galcantray, south-west of Cawdor. The site was dug up between 1984 and 1988. Several features were found that support it being a Roman fort. Roman pottery similar to that found at Inchtuthil Roman fort has been discovered. If confirmed, it would be one of the most northerly known Roman forts in the British Isles.

The idea that Roman armies went even further north in Scotland is suggested by discoveries in Easter Ross. Temporary camp sites were proposed at Portmahomack in 1949, though this hasn't been fully confirmed. In 1991, an investigation of Tarradale on the Black Isle near the Beauly Firth concluded that "the site appears to conform to the morphology of a Roman camp or fort."

Rome's Lasting Impact on Scotland

Historical Legacy

The Roman military was present in most of Scotland for little more than 40 years, and for only about 80 years in total anywhere. It's now generally thought that at no point was even half of Scotland's land under Roman control.

Scotland gained two main things from the Roman period, mostly indirectly. These are the use of the Latin writing system for its languages and the rise of Christianity as the main religion. Through Christianity, the Latin language would be used by the people of Scotland for church and government for many more centuries.

Roman influence helped Christianity spread across Europe. But there is little proof of a direct link between the Roman Empire and Christian missions north of Hadrian's Wall. Traditionally, Saint Ninian is believed to be the first bishop active in Scotland. He is briefly mentioned by Bede, who says that around 397 AD, Ninian set up his base at Whithorn in south-west Scotland. He built a stone church there, known as Candida Casa. More recently, some have suggested that Ninian was actually the 6th-century missionary Finnian of Moville. Either way, Roman influence on early Christianity in Scotland does not seem to have been very strong.

Even though it was mostly a series of short military occupations, Imperial Rome was harsh and brutal in achieving its goals. Killing large groups of people was a common part of its foreign policy. It's clear that the invasions and occupations cost thousands of lives. Historian Alistair Moffat writes:

The reality is that the Romans came to what is now Scotland, they saw, they burned, killed, stole and occasionally conquered, and then they left a tremendous mess behind them, clearing away native settlements and covering good farmland with the remains of ditches, banks, roads, and other sorts of ancient military debris. Like most imperialists they arrived to make money, to gain political advantage and to exploit the resources of their colonies at virtually any price to the conquered. And remarkably, in Britain, in Scotland, we continue to admire them for it.

It's even more surprising given that the Vindolanda tablets show that the Roman nickname for the local people in northern Britain was Brittunculi, meaning "nasty little Britons".

Similarly, William Hanson concludes:

For many years it has been almost axiomatic in studies of the period that the Roman conquest must have had some major medium or long-term impact on Scotland. On present evidence that cannot be substantiated either in terms of environment, economy, or, indeed, society. The impact appears to have been very limited. The general picture remains one of broad continuity, not of disruption.... The Roman presence in Scotland was little more than a series of brief interludes within a longer continuum of indigenous development."

The Romans' role in clearing the once vast Caledonian forest is still debated. That these forests were once much larger than they are now is not questioned. But when and why they shrunk is. The 16th-century writer Hector Boece believed that in Roman times, the woods stretched north from Stirling into Atholl and Lochaber. He said they were home to white bulls with "crisp and curland mane, like feirs lionis". Later historians like P. F. Tytler and W. F. Skene agreed, as did the 20th-century naturalist Frank Fraser Darling. Modern methods, like studying pollen and tree rings, suggest a more complex story. Changing climates after the ice age might have allowed for the most forest cover between 4000 and 3000 BC. Deforestation in the Southern Uplands, caused by both climate and humans, was already happening when the Romans arrived. Detailed studies of Black Loch in Fife suggest that farmland grew at the expense of forest from about 2000 BC until the Roman advance in the 1st century AD. After that, birch, oak, and hazel trees grew back for 500 years. This suggests the invasions had a very negative impact on the native population. It's harder to know what happened outside the Roman-held areas, but Rome's long-term influence might not have been significant.

The archaeological remains of Rome in Scotland are interesting, but few, especially in the north. Almost all the sites are military, including about 650 kilometres (400 miles) of roads. Overall, it's hard to find any direct links between native buildings and settlement patterns and Roman influence. In other parts of Europe, new kingdoms and languages grew from the remains of the once-mighty Roman world. In Scotland, the Celtic Iron Age way of life, often troubled but never destroyed by Rome, simply returned. In the north, the Picts continued to be the main power before the arrival and later control of the Scots from Dalriada. The Damnonii eventually formed the Kingdom of Strathclyde, based at Dumbarton Rock. South of the Forth, the Welsh-speaking Brythonic kingdoms of Yr Hen Ogledd (English: "The Old North") thrived during the 5th–7th centuries.

The most lasting Roman legacy might be Hadrian's Wall. Its line is very close to the modern border between Scotland and England. It created a division between the northern third and southern two-thirds of Great Britain. This division still plays a part in modern political discussions. However, this is probably just a coincidence, as there is little to suggest its influence was important in the early Medieval period after Rome fell.

Rome in Fiction

The 9th Spanish Legion took part in the Roman invasion of Britain. It suffered losses under Quintus Petillius Cerialis during the rebellion of Boudica in 61 AD. It set up a fortress in 71 AD that later became part of Eburacum. Although some writers have claimed that the 9th Legion disappeared in 117 AD, there are records of it after that year. It was probably destroyed in the eastern part of the Roman Empire. For a time, some British historians believed that the legion vanished during its conflicts in what is now Scotland. This idea was used in the novels The Eagle of the Ninth by Rosemary Sutcliff, Legion From the Shadows by Karl Edward Wagner, Red Shift by Alan Garner, Engine City by Ken MacLeod, Warriors of Alavna by N. M. Browne. It was also used in the films The Last Legion, Centurion, and The Eagle.

Images for kids

-

Arthur's O'on, a Roman monument at Stenhousemuir near Falkirk, from Alexander Gordon's 1726 work Itinerarium Septentrionale. It was demolished 17 years later in 1743.

-

Forts and fortlets associated with the Antonine Wall from west to east: Bishopton, Old Kilpatrick, Duntocher, Cleddans, Castlehill, Bearsden, Summerston, Balmuildy, Wilderness Plantation, Cadder, Glasgow Bridge, Kirkintilloch, Auchendavy, Bar Hill, Croy Hill, Westerwood, Castlecary, Seabegs, Rough Castle, Camelon, Watling Lodge, Falkirk, Mumrills, Inveravon, Kinneil, Carriden

See also

In Spanish: Escocia durante el Imperio romano para niños

In Spanish: Escocia durante el Imperio romano para niños