Domitian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Domitian |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 14 September 81 – 18 September 96 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Titus | ||||||||

| Successor | Nerva | ||||||||

| Born | 24 October 51 Rome, Italy, Roman Empire |

||||||||

| Died | 18 September 96 (aged 44) Rome, Italy |

||||||||

| Burial | Rome | ||||||||

| Spouse | Domitia Longina (70–96) | ||||||||

| Issue | Flavius Caesar Flavia Vespasian Minor (possibly adopted) Domitian Minor (possibly adopted) |

||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Dynasty | Flavian | ||||||||

| Father | Vespasian | ||||||||

| Mother | Domitilla | ||||||||

Domitian (born October 24, 51 – died September 18, 96) was a Roman emperor who ruled from 81 to 96 AD. He was the son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, both of whom were also emperors. Domitian was the last ruler from the Flavian dynasty.

He was known as a strong but strict leader. His way of ruling often caused problems with the Senate, the Roman government body, because he greatly reduced their power.

Domitian had a small role during the reigns of his father and brother. After his brother Titus died, Domitian was made emperor by the Praetorian Guard, the emperor's personal bodyguards. His 15-year reign was one of the longest since Emperor Tiberius. As emperor, Domitian made the economy stronger by improving Roman money. He also made the empire's borders safer and started many building projects to fix Rome after fires.

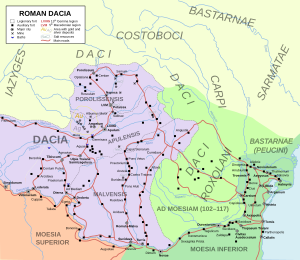

Important wars happened in Britain, where his general Agricola tried to conquer Caledonia (which is now Scotland). There were also wars in Dacia, where Domitian could not win a clear victory against King Decebalus. Domitian's government was very strict. He used religious, military, and cultural messages to make people admire him greatly. He also named himself a "perpetual censor," which meant he could control public and private behavior.

Because of this, Domitian was liked by the common people and the army. However, members of the Roman Senate saw him as a harsh ruler. Domitian's reign ended in 96 AD when he was killed by officials in his court. His advisor Nerva became emperor the same day. After Domitian's death, the Senate tried to erase his memory, a process called damnatio memoriae. Writers like Tacitus and Suetonius wrote about him as a cruel and suspicious tyrant. But modern historians now see Domitian as a strong and effective leader. His programs in culture, economy, and politics helped create a peaceful period in the 2nd century.

Contents

Early Life

Family and Background

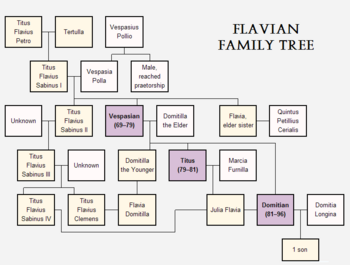

Domitian was born in Rome on October 24, 51 AD. He was the youngest son of Vespasian and Domitilla the Elder. He had an older sister, Domitilla the Younger, and an older brother, Titus. In the 1st century BC, many civil wars had weakened Rome's old noble families. New families from Italy slowly became more important. One of these families was the Flavians, who became very powerful in just four generations. They gained wealth and status under the emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Domitian's great-grandfather, Titus Flavius Petro, was a centurion (a military officer) under Pompey. His military career ended badly. But Petro improved his family's standing by marrying Tertulla, a very rich woman. Her money helped her son, Titus Flavius Sabinus I (Domitian's grandfather), rise in society. Sabinus I earned more wealth as a tax collector and banker. By marrying Vespasia Polla, he connected the Flavian family to the more respected Vespasia family. This helped his sons, Titus Flavius Sabinus II and Vespasian, become senators.

Vespasian, Domitian's father, had a successful political career. He held offices like quaestor, aedile, and praetor. He became a consul in 51 AD, the year Domitian was born. As a military leader, Vespasian became famous during the Roman invasion of Britain in 43 AD. Some old stories said the Flavian family was poor when Domitian was young. But modern historians say these stories were probably made up later. They were part of a plan to make the Flavians look better than earlier emperors.

The Flavians seemed to be in high favor with the emperors during the 40s and 60s. Titus, Domitian's brother, even got a court education with the emperor's son. Vespasian continued his successful career. After a break in the 50s, he returned to public service under Emperor Nero. In 66 AD, Jews in the province of Judaea rebelled against Rome. This started the First Jewish–Roman War. Vespasian was chosen to lead the Roman army against the rebels. Titus, who had finished his military training, led a legion (a large army unit).

Youth and Personality

Domitian ruled longer than his father and brother. But his youth was spent mostly in his older brother's shadow. Titus became famous during the Jewish–Roman War. After their father Vespasian became emperor in 69 AD, Titus held many important jobs. Domitian received honors but no real responsibilities. By the time he was 16, his mother and sister had died. His father and brother were always away fighting wars. This meant Domitian spent much of his teenage years without his close family.

During the Jewish–Roman wars, his uncle, Titus Flavius Sabinus II, probably took care of him. His uncle was the city prefect of Rome. Or perhaps Nerva, a loyal friend of the Flavians and Domitian's future successor, cared for him. Domitian received the education of a young man from a privileged family. He studied rhetoric (the art of speaking well) and literature. The writer Suetonius said Domitian could quote famous poets like Homer and Virgil. He described Domitian as a smart and educated young man who spoke elegantly. Domitian's first published works included poetry and writings on law. Unlike Titus, Domitian did not get a court education. It's not clear if he had formal military training. But Suetonius said he was very good with a bow and arrow.

Domitian was said to be very sensitive about his baldness. Later in life, he wore wigs to hide it. Suetonius even claimed Domitian wrote a book about hair care. Historians find it hard to understand Domitian's true personality because the old writings about him are biased. But some things are clear. He seemed to lack the natural charm of his brother and father. He was often suspicious and sometimes had a strange sense of humor. He also often spoke in confusing ways. As he got older, he preferred to be alone. This might have been because he grew up feeling isolated. By the age of eighteen, almost all his close relatives had died. The political chaos of the 60s, which brought his family to power, strongly shaped Domitian's early years.

Rise of the Flavians

Year of the Four Emperors

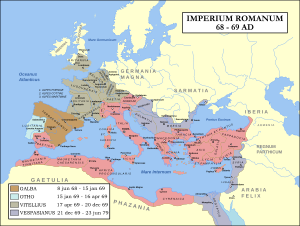

After Emperor Nero died on June 9, 68 AD, the Julio-Claudian dynasty ended. This led to a year of civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors. Four powerful Roman generals—Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian—fought to become emperor. Vespasian heard about Nero's death while he was preparing to attack the city of Jerusalem. At the same time, the Senate had named Galba, then governor of Spain, as Emperor of Rome. Vespasian decided to wait for orders and sent Titus to meet the new Emperor.

Before reaching Italy, Titus learned that Galba had been killed. Otho, the governor of Portugal, had replaced him. Also, Vitellius and his armies in Germany had rebelled. They were marching on Rome to overthrow Otho. Titus did not want to be caught between the two sides. So, he went back to his father in Judaea.

Otho and Vitellius knew the Flavian family was a threat. Vespasian had four legions, about 80,000 soldiers. His position in Judaea also meant he was close to Egypt, which controlled Rome's food supply. His brother, Titus Flavius Sabinus II, was the city prefect and commanded Rome's entire city guard. Flavian soldiers were eager to fight. But Vespasian waited until either Galba or Otho was out of power. When Vitellius defeated Otho, the armies in Judaea and Egypt declared Vespasian emperor on July 1, 69 AD. Vespasian agreed and joined forces with Gaius Licinius Mucianus, the governor of Syria, against Vitellius. A strong army from Judaea and Syria marched on Rome under Mucianus. Vespasian went to Alexandria, leaving Titus to finish the Jewish rebellion.

In Rome, Vitellius kept Domitian under house arrest. This was to prevent the Flavians from attacking. Support for Vitellius weakened as more legions joined Vespasian. On October 24, 69 AD, Vitellius's and Vespasian's armies fought. Vitellius's forces were badly defeated. Vitellius tried to surrender and give up his power. But the Praetorian Guard thought this was shameful. They stopped him from doing it. On December 18, the emperor tried to leave his imperial symbols at a temple. But at the last minute, he went back to his palace. In the confusion, important leaders gathered at Sabinus's house and declared Vespasian emperor. But Vitellius's soldiers fought Sabinus's guards. Sabinus had to retreat to the Capitoline Hill.

During the night, Domitian and other relatives joined him. Mucianus's armies were nearing Rome. But the Flavians on the Capitol could not hold out for long. On December 19, Vitellius's men stormed the Capitol. Sabinus was captured and killed. Domitian escaped by dressing as a worshipper of Isis. He spent the night safely with one of his father's supporters. By the afternoon of December 20, Vitellius was dead. His armies were defeated by the Flavian legions. Domitian came out to meet the invading forces. He was greeted as "Caesar" and taken to his father's house. The next day, December 21, the Senate declared Vespasian emperor of the Roman Empire.

After the War

Even though the war was over, there was still chaos in Rome for a few days. Order was restored by Mucianus in early 70 AD. But Vespasian did not arrive in Rome until September of that year. During this time, Domitian acted as the Flavian family's representative in the Roman Senate. He was given the title of "Caesar" and made a praetor with consular power. The ancient historian Tacitus said Domitian's first speech in the Senate was short and careful. He also noted Domitian's skill at avoiding difficult questions. Domitian's power was only in name. This showed what his role would be for at least ten more years. Mucianus held the real power while Vespasian was away. He made sure Domitian, who was only eighteen, did not overstep his authority.

Mucianus also controlled Domitian's close friends. He moved Flavian generals like Arrius Varus and Antonius Primus away. He replaced them with more loyal men. Mucianus also limited Domitian's military ambitions. The civil war of 69 AD had made the provinces unstable. This led to local uprisings, like the Batavian rebellion in Gaul. Batavian soldiers, led by Gaius Julius Civilis, rebelled with help from a group of Treveri. Seven legions were sent from Rome, led by Vespasian's brother-in-law.

The rebellion was quickly put down. But exaggerated reports of disaster made Mucianus leave Rome with more troops. Domitian eagerly wanted military glory. He joined the other officers, hoping to lead his own legion. Tacitus said Mucianus did not like this idea. But he thought Domitian was a problem no matter what job he had. So, he preferred to keep Domitian close rather than in Rome. When news arrived that the rebellion was defeated, Mucianus cleverly stopped Domitian from seeking more military adventures. Domitian then wrote to the general, suggesting he hand over command of his army. But again, he was ignored. When Vespasian returned in September, Domitian's political role became almost useless. He then spent his time on arts and literature.

Marriage

While his political and military career was disappointing, Domitian's personal life was more successful. In 70 AD, Vespasian tried to arrange a marriage for Domitian with Titus's daughter, Julia Flavia. But Domitian was determined to marry Domitia Longina. He even convinced her husband to divorce her so he could marry her. This marriage was very good for both families. Domitia Longina was the younger daughter of Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, a respected general. She was also a descendant of Emperor Augustus.

In 80 AD, Domitia and Domitian had their only known son. His name is not known, but he died as a child in 83 AD. Soon after becoming emperor, Domitian gave Domitia the special title of Augusta. Their son was made a god after his death. His image appeared on coins from that time. However, their marriage seemed to have problems in 83 AD. For unknown reasons, Domitian briefly sent Domitia away. But he soon called her back. This might have been because he loved her, or because of rumors that he was having a relationship with his niece. Historian Brian Jones believes it was most likely because she failed to have another heir. By 84 AD, Domitia was back in the palace. She lived there for the rest of Domitian's reign without further issues. We don't know much about Domitia's activities as empress or how much power she had. But her role seemed limited. We know she went with the Emperor to the amphitheatre. The Jewish writer Josephus said she helped him. It is not known if Domitian had other children, but he did not marry again. Their marriage seems to have been happy.

Ceremonial Heir (71–81)

Before becoming Emperor, Domitian's role in the Flavian government was mostly for show. In June 71 AD, Titus returned victorious from the war in Judaea. The rebellion had caused tens of thousands of deaths, mostly Jewish people. The city and temple of Jerusalem were completely destroyed. Roman soldiers took its most valuable treasures. Nearly 100,000 people were captured and enslaved. For his victory, the Senate gave Titus a Roman triumph (a grand parade). On the day of the celebration, the Flavian family rode into Rome. A lavish parade showing the spoils of war went before them. Vespasian and Titus led the family procession. Domitian, riding a magnificent white horse, followed with the other Flavian relatives.

Leaders of the Jewish resistance were executed in the Roman Forum. After that, the parade ended with religious sacrifices at the Temple of Jupiter. A triumphal arch, the Arch of Titus, was built to remember the end of the war. But Titus's return made Domitian's unimportance even clearer. Titus was the oldest and most experienced son. He shared power with his father, held seven consulships, and was given command of the Praetorian Guard. These powers showed he was the chosen heir. As the second son, Domitian held honorary titles like "Caesar" and "Princeps Iuventutis" (Leader of the Youth). He also had several priesthoods. But he had no office with real power. He held six consulships during Vespasian's reign. But only one, in 73 AD, was a full consulship. The others were less important "suffect consulships." He usually took over from his father or brother in mid-January.

These ceremonial roles gave Domitian valuable experience in the Roman Senate. They might have made him doubt the Senate's importance later. Under Vespasian and Titus, non-Flavians were mostly kept out of important public jobs. Mucianus himself almost disappeared from historical records during this time. It is believed he died between 75 and 77 AD. Real power was clearly held by the Flavian family. The weakened Senate only pretended to be a democracy. Titus acted like a co-emperor with his father. So, there was no sudden change in Flavian policy when Vespasian died on June 24, 79 AD. Titus told Domitian that he would soon share full power in the government. But Domitian did not receive any real power during Titus's short reign.

Two major disasters happened in 79 and 80 AD. In October/November 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius erupted. It buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum under ash and lava. The next year, a fire in Rome lasted three days. It destroyed many important public buildings. Titus spent much of his reign helping with relief efforts and fixing damaged property. On September 13, 81 AD, after only two years as emperor, he suddenly died of a fever. Some ancient writers said Domitian was involved in his brother's death. They even claimed Domitian openly plotted against him. It is hard to know if these claims are true because the surviving writings are biased. Brotherly affection was probably low. This was not surprising, as Domitian had barely seen Titus after age seven. Whatever their relationship, Domitian seemed to show little sadness when his brother was dying. Instead, he went to the Praetorian camp, where he was declared emperor. The next day, September 14, the Senate confirmed Domitian's powers. They gave him the title of pontifex maximus (chief priest), and the titles of Augustus ("venerable") and Pater Patriae ("father of the country").

Emperor (81–96)

His Rule

As emperor, Domitian quickly stopped pretending that the Senate had much power. His father and brother had kept up this pretense. Domitian moved the center of government to his imperial court. This openly made the Senate's powers useless. According to Pliny the Younger, Domitian believed the Roman Empire should be ruled by a divine monarch. He saw himself as a good ruler with absolute power. Domitian also believed the emperor should guide the Roman people in culture and morals. To start this new era, he began big projects in economy, military, and culture. He wanted to bring the Empire back to the glory it had under Emperor Augustus.

Despite these big plans, Domitian was determined to govern the Empire carefully and honestly. He personally got involved in all parts of the government. He issued rules for small details of daily life and law. Taxes and public morals were strictly enforced. According to Suetonius, the imperial government worked very well under Domitian. His high standards and suspicious nature kept corruption among governors and officials very low. He did not pretend the Senate was important under his rule. He removed senators he thought were unworthy. He rarely gave important public jobs to family members. This was different from his father and brother, who often gave jobs to relatives.

Most importantly, Domitian valued loyalty in those he chose for important positions. He found these qualities more often in men from the equestrian class than in senators or his own family. He was suspicious of his family and senators. He quickly removed them from office if they disagreed with his policies. Domitian's absolute rule was also clear because he spent much time away from Rome. Since the Senate's power had been declining, under Domitian, the center of power was wherever the Emperor was. Until his palace on the Palatine Hill was finished, the imperial court was in other towns. Domitian traveled widely in Europe. He spent at least three years of his reign in Germany and Illyricum, leading military campaigns on the empire's borders.

Palaces and Buildings

Domitian built many grand buildings for himself. This included the Villa of Domitian, a huge and luxurious palace 20 km (12 miles) outside Rome. In Rome itself, he built the Palace of Domitian on the Palatine Hill. Seven other villas are also linked to Domitian in different places. Only one of them has been clearly identified.

The Stadium of Domitian was opened in 86 AD. It was a gift to the people of Rome, part of a building plan after a fire in 79 AD. It was Rome's first permanent place for athletic contests. Today, the Piazza Navona stands where it once was. In Egypt, Domitian also built and decorated many structures. He appears with Trajan in scenes on the gate of the Temple of Hathor in Dendera. His name also appears on columns of the Temple of Khnum at Esna.

Economy

Domitian's close attention to detail was very clear in his financial policies. Historians have debated whether Domitian left the Roman Empire in debt or with extra money when he died. Most evidence suggests the economy was balanced for most of his reign. When he became emperor, he greatly improved Roman money. He increased the silver in the denarius coin from 90% to 98%. This meant the actual silver weight went from 2.87 grams to 3.26 grams. A financial problem in 85 AD forced him to reduce the silver purity and weight slightly. But the new values were still higher than what Vespasian and Titus had used. Domitian's strict tax policy kept this standard for the next eleven years. Coins from this time show very high quality. They have careful details of Domitian's titles and refined artwork.

Historian Brian Jones estimates Domitian's yearly income was over 1.2 billion sestertii. More than a third of this would have been spent on the Roman army. Another major cost was the huge rebuilding of Rome. When Domitian became emperor, the city was still recovering from the Great Fire of 64 AD, the civil war of 69 AD, and a fire in 80 AD. Domitian's building program was more than just repairs. It was meant to be the greatest achievement of a cultural rebirth across the Empire. About fifty buildings were built, restored, or finished. Only Emperor Augustus built more. Among the most important new buildings were an odeon (a small theater), a stadium, and a large palace on the Palatine Hill called the Flavian Palace. Domitian's main architect designed it. The most important building Domitian restored was the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. It was said to have a golden roof. He also finished the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, the Arch of Titus, and the Flavian Amphitheatre (Colosseum). He added a fourth level and finished the seating inside the Colosseum.

To please the people of Rome, an estimated 135 million sestertii were spent on gifts throughout Domitian's reign. The Emperor also brought back public banquets, which had become simple food distributions under Nero. He spent large sums on entertainment and games. In 86 AD, he started the Capitoline Games. This was a competition held every four years. It included athletic displays, chariot racing, and contests for public speaking, music, and acting. Domitian himself helped competitors from all over the Empire travel to Rome. He also gave out the prizes. New things were also added to the regular gladiator games. These included naval battles, nighttime fights, and fights with female and dwarf gladiators. Finally, he added two new teams to the chariot races, Gold and Purple, to race against the existing White, Red, Green, and Blue teams.

Military Campaigns

The military campaigns during Domitian's reign were mostly for defense. The Emperor did not want to expand the empire through war. His most important military contribution was building the Limes Germanicus. This was a huge network of roads, forts, and watchtowers along the Rhine river to defend the Empire. However, several important wars were fought in Gaul against the Chatti people. There were also wars along the Danube river against the Suebi, the Sarmatians, and the Dacians.

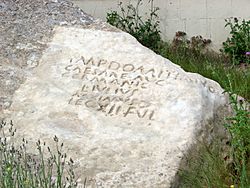

The conquest of Britain continued under General Gnaeus Julius Agricola. He expanded the Roman Empire as far as Caledonia, which is modern-day Scotland. Domitian also created a new legion in 82 AD, called the Legio I Minervia, to fight against the Chatti. Domitian's name is also on the easternmost evidence of Roman military presence. This is a rock inscription in modern Azerbaijan. Based on the titles carved, the march happened between 84 and 96 AD.

Domitian managed the Roman army with the same careful attention he showed in other parts of government. However, his skills as a military planner were criticized by people at the time. Although he claimed several victories, these were mostly for show. Tacitus called Domitian's victory against the Chatti a "mock triumph." He also criticized Domitian's decision to retreat in Britain after Agricola's conquests. Nevertheless, Domitian seemed very popular among the soldiers. He spent about three years of his reign with the army on campaigns. This was more than any emperor since Augustus. He also raised their pay by one-third. While army commanders might not have liked his decisions, the loyalty of the common soldier was strong.

War Against the Chatti

Once he was emperor, Domitian immediately wanted to achieve military glory. As early as 82 or 83 AD, he went to Gaul. He said he was there to count the population. But he suddenly ordered an attack on the Chatti people. For this, a new legion, Legio I Minervia, was created. It built about 75 kilometers (46 miles) of roads through Chatti territory to find the enemy. We don't have much information about the battles. But enough early victories were won for Domitian to be back in Rome by the end of 83 AD. There, he celebrated a grand victory parade and took the title Germanicus. Ancient writers often made fun of Domitian's supposed victory. They called the campaign "unnecessary" and a "mock triumph." There is some truth to these claims, as the Chatti later played a big role in a rebellion in 89 AD.

Conquest of Northern Britain (77–84)

One of the most detailed reports of military activity under the Flavian dynasty was written by Tacitus. His book about his father-in-law, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, mostly covers the conquest of northern Britain between 77 and 84 AD. Agricola arrived around 77 AD as governor of Roman Britain. He immediately started campaigns into Caledonia (modern Scotland). In 82 AD, Agricola crossed a body of water and defeated people unknown to the Romans until then. He fortified the coast facing Ireland. Tacitus wrote that his father-in-law often said Ireland could be conquered with just one legion and a few extra soldiers. Agricola had given shelter to an exiled Irish king. He hoped to use him as an excuse for conquest. This conquest never happened. But some historians believe the crossing was a small exploration or punishment trip to Ireland.

The next year, Agricola turned his attention from Ireland. He gathered a fleet and pushed beyond the River Forth into Caledonia. To help this advance, a large legionary fortress was built at Inchtuthil. In the summer of 84 AD, Agricola faced the armies of the Caledonians. They were led by Calgacus at the Battle of Mons Graupius. The Romans caused heavy losses to the enemy. But two-thirds of the Caledonian army escaped and hid in the Scottish marshes and Highlands. This stopped Agricola from fully controlling the entire British island. In 85 AD, Domitian called Agricola back to Rome. Agricola had served as governor for more than six years, which was longer than usual.

Tacitus claimed that Domitian recalled Agricola because Agricola's successes made the Emperor's own small victories in Germany look bad. The relationship between Agricola and the Emperor is unclear. On one hand, Agricola received honors and a statue. On the other hand, Agricola never held another civil or military job, despite his experience. He was offered the governorship of Africa but refused it. This was either due to illness or, as Tacitus claimed, Domitian's plotting. Not long after Agricola was recalled from Britain, the Roman Empire went to war with the Kingdom of Dacia in the East. More soldiers were needed. In 87 or 88 AD, Domitian ordered a large withdrawal of troops from Britain. The fortress at Inchtuthil was taken apart. The Caledonian forts were abandoned. The Roman border moved about 120 kilometers (75 miles) further south. The army commanders might have disliked Domitian's decision to retreat. But for him, the Caledonian lands were just a drain on Rome's money.

Dacian Wars (85–88)

The biggest threat to the Roman Empire during Domitian's reign came from the northern provinces. Here, the Suebi, Sarmatians, and Dacians constantly attacked Roman settlements along the Danube river. The Sarmatians and Dacians were the most dangerous. Around 84 or 85 AD, the Dacians, led by King Decebalus, crossed the Danube into the province of Moesia. They caused great damage and killed the Moesian governor. Domitian quickly launched a counterattack. He personally traveled to the region with a large force. His praetorian prefect commanded it. This prefect successfully drove the Dacians back across the border in mid-85 AD. This led Domitian to return to Rome and celebrate his second victory parade.

However, the victory did not last long. In 86 AD, the prefect led a failed expedition into Dacia. The prefect was killed, and the battle standard of the Praetorian Guard was lost. Losing the battle standard, or aquila, meant a terrible defeat and a serious insult to Roman pride. Domitian returned to Moesia in August 86 AD. He divided the province into Lower Moesia and Upper Moesia. He also moved three more legions to the Danube. In 87 AD, the Romans invaded Dacia again. This time, a new commander led them. They finally defeated Decebalus in late 88 AD at the same place where the prefect had died. An attack on the Dacian capital was stopped when new problems arose on the German border in 89 AD.

To avoid fighting a war on two fronts, Domitian agreed to a peace treaty with Decebalus. He allowed Roman troops to pass through Dacia. In return, he gave Decebalus an annual payment of 8 million sesterces. Writers at the time strongly criticized this treaty. They thought it was shameful for the Romans and left the deaths of the Roman commanders unavenged. For the rest of Domitian's reign, Dacia remained a relatively peaceful kingdom allied with Rome. But Decebalus used the Roman money to strengthen his defenses. Domitian probably wanted a new war against the Dacians. He reinforced Upper Moesia with more cavalry and soldiers. Emperor Trajan continued Domitian's policy. He added more units to the army in Upper Moesia. Then he used these troops for his Dacian wars. The Romans finally won a decisive victory against Decebalus in 106 AD. The Roman army suffered heavy losses again. But Trajan captured the Dacian capital and, importantly, took control of the Dacian gold and silver mines.

Religious Policy

Domitian strongly believed in the traditional Roman religion. He personally made sure that old customs and morals were followed throughout his reign. To show that the Flavian family's rule was divine, Domitian emphasized their connection to the chief god Jupiter. The impressive restoration of the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill was a major part of this. A small chapel dedicated to Jupiter Conservator (Jupiter the Preserver) was also built near the house where Domitian had found safety in 69 AD. Later, he replaced it with a larger building, dedicated to Jupiter Custos (Jupiter the Guardian). However, the goddess he worshipped most eagerly was Minerva. He had a personal shrine to her in his bedroom. She often appeared on his coins. He also named a legion, Legio I Minervia, after her.

Domitian also brought back the practice of the imperial cult. This was the worship of the emperor and his family as gods. It had become less common under Vespasian. Importantly, Domitian's first act as emperor was to declare his brother Titus a god. When they died, his infant son and niece were also made gods. Regarding the emperor himself as a religious figure, some ancient writers claimed Domitian officially called himself Dominus et Deus ("Lord and God"). However, he rejected the title Dominus during his reign. Since he issued no official documents or coins with this title, historians like Brian Jones believe such phrases were used by flatterers who wanted favors from him. To encourage the worship of the imperial family, he built a family tomb on the Quirinal Hill. He also finished the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, a shrine dedicated to his deified father and brother. To remember the Flavian family's military victories, he ordered the building of other temples and finished the Arch of Titus.

Building projects were only the most visible part of Domitian's religious policy. He also focused on following religious law and public morals. In 85 AD, he named himself "perpetual censor." This office was in charge of overseeing Roman morals and behavior. Domitian carried out this task carefully and dutifully.

Domitian also strongly punished corruption among public officials. He removed jurors who took bribes and canceled laws if he suspected a conflict of interest. He made sure that writings that insulted people, especially himself, were punished by exile or death. Actors were also viewed with suspicion. He forbade mimes from performing on public stages. Philosophers did not fare much better. Epictetus, a philosophy professor in Rome, said philosophers could "look tyrants steadily in the face." Domitian's decree in 94 AD expelled all philosophers from Rome. This caused Epictetus to move to Greece, where he lived simply and safely.

Foreign religions were allowed as long as they did not disturb public order or could be mixed with traditional Roman religion. The worship of Egyptian gods especially grew under the Flavian dynasty. This was not seen again until the reign of Commodus. The worship of Serapis and Isis, who were linked to Jupiter and Minerva, was very popular. Writings from the fourth century claim that Jews and Christians were heavily persecuted towards the end of Domitian's reign. Some believe the Book of Revelation and First Epistle of Clement were written during this time. The latter mentions "sudden and repeated misfortunes," which are thought to refer to persecutions under Domitian. Although Jews were heavily taxed, no writers from that time give specific details of trials or executions based on religious offenses other than those within the Roman religion.

Opposition

Governor Saturninus's Revolt (89 AD)

On January 1, 89 AD, the governor of Upper Germany, Lucius Antonius Saturninus, and his two legions rebelled against the Roman Empire. They were helped by the Germanic Chatti people. The exact reason for the rebellion is not certain. But it seems to have been planned well in advance. Senate officers might have disliked Domitian's military plans. These included his decision to strengthen the German border instead of attacking, his recent retreat from Britain, and his shameful policy of peace with Decebalus. In any case, the uprising was only in Saturninus's province. It was quickly discovered when rumors spread to neighboring provinces. The governor of Lower Germany moved to the region at once. He was helped by a Roman official from Rhaetia. From Spain, General Trajan was called. Domitian himself came from Rome with the Praetorian Guard.

By luck, a thaw prevented the Chatti from crossing the Rhine river to help Saturninus. Within twenty-four days, the rebellion was crushed. Its leaders were severely punished. The rebellious legions were sent to the front in Illyricum. Those who helped defeat them were rewarded. The governor of Lower Germany received the governorship of Syria. He also got a second consulship and a priesthood. Domitian started the year after the revolt by sharing the consulship with Nerva. This suggests Nerva played a part in uncovering the plot. Perhaps he helped in a similar way he did during a conspiracy under Nero. We know little about Nerva's life before he became emperor in 96 AD. But he seems to have been a very adaptable diplomat. He survived many changes in power and became one of the Flavians' most trusted advisors. His consulship might have been meant to show the stability of the government. The revolt was suppressed, and the Empire returned to order.

Relationship with the Senate

Since the fall of the Republic, the power of the Roman Senate had largely decreased. This was due to the system of government set up by Augustus, called the Principate. The Principate allowed a ruler to have almost total power. But it kept the formal structure of the Roman Republic. Most emperors kept up the public appearance of democracy. In return, the Senate quietly accepted the emperor's status as a true monarch. Some rulers handled this arrangement less subtly than others. Domitian was not subtle. He often came to the Senate as a victor and conqueror to show his dislike for them. From the start of his reign, he made it clear that he had absolute power. He disliked noble families and was not afraid to show it. He took away all decision-making power from the Senate. He reduced its role to just administration. Instead, he relied on a small group of friends and equestrians to control important state offices.

The dislike was mutual. After Domitian was killed, the senators in Rome rushed to the Senate house. They immediately passed a motion to erase his memory, called damnatio memoriae. Under the emperors who came after him, writers from the Senate published histories that described Domitian as a tyrant. However, evidence suggests that Domitian did try to make concessions to the Senate. His father and brother had mostly kept consular power within the Flavian family. But Domitian allowed a surprisingly large number of people from the provinces and potential opponents to become consul. He let them start the official year as ordinary consuls. It's not clear if this was a real attempt to make peace with hostile groups in the Senate. By offering the consulship to potential opponents, Domitian might have wanted to make these senators look bad to their supporters. When their behavior was not good enough, they were almost always put on trial and exiled or executed. Their property was taken away.

Both Tacitus and Suetonius wrote about increasing persecutions towards the end of Domitian's reign. They said there was a sharp increase around 93 AD, or sometime after the failed revolt in 89 AD. At least twenty senators were executed. These included Domitia Longina's former husband and three of Domitian's own family members. One cousin was even named by Domitian as a possible successor. However, some of these men were executed as early as 83 or 85 AD. This makes Tacitus's idea of a "reign of terror" late in Domitian's reign less believable.

Historian Jones compares Domitian's executions to those under Emperor Claudius (41–54 AD). Claudius executed about 35 senators and 300 equestrians. Yet, the Senate still declared him a god and saw him as a good emperor. Domitian was apparently unable to gain support among the noble class. This was true even though he tried to please hostile groups by appointing them as consuls. His absolute style of government highlighted the Senate's loss of power. His policy of treating nobles and even family members as equal to all other Romans earned him their contempt.

Death and Succession

Domitian was killed on September 18, 96 AD, in a plot by court officials. The Fasti Ostienses, an ancient Roman calendar, records that on the same day, the Senate declared Nerva emperor.

Flavian Family Tree

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

Ancient Sources

The traditional view of Domitian is usually negative. This is because most ancient sources were connected to the Senate or noble class. Domitian had very difficult relationships with these groups. Also, historians like Pliny the Younger, Tacitus, and Suetonius all wrote about his reign after it had ended. By then, his memory had been condemned by the Senate. The works of Domitian's court poets are almost the only writings from his actual reign. Not surprisingly, these poems highly praised Domitian. They said his achievements were equal to those of the gods. The most detailed account of Domitian's life that still exists was written by the historian Suetonius. He was born during Vespasian's reign and published his works under Emperor Hadrian (117–138 AD). His book is the source of much of what we know about Domitian. Although his text is mostly negative, it does not only condemn or praise Domitian. It says his rule started well but slowly became a time of terror. However, the biography is confusing because it seems to contradict itself about Domitian's rule and personality.

According to Suetonius, Domitian only pretended to be interested in arts and literature. He supposedly never bothered to read classic authors. Other parts of the book, which mention Domitian's love for clever sayings, suggest he was familiar with classic writers. He also supported poets and architects. He started artistic competitions. He personally rebuilt Rome's library at great cost after it burned down.

Modern Views

During the 20th century, Domitian's military, government, and economic policies were re-examined. Negative views of Domitian had been common. But new discoveries from archaeology and coin studies brought fresh attention to his reign. This made it necessary to rethink the old stories written by Tacitus and Pliny. It took almost a hundred years after a book about Domitian was published in 1894 before new, full-length studies appeared. The first of these was Brian Jones's 1992 book, The Emperor Domitian. He concluded that Domitian was a strong but effective ruler. For most of his reign, there was no widespread unhappiness with his policies. His harshness was limited to a small group of people who spoke out against him. These people exaggerated his strictness to favor the emperors who followed him. His foreign policy was practical. He avoided wars of expansion and made peace when Roman military tradition called for aggressive conquest. There was no persecution of religious minorities, like Jews and Christians.

In 1930, Ronald Syme argued for a complete re-evaluation of Domitian's financial policy. This policy had mostly been seen as a disaster. But his economic program was very efficient. It kept Roman money at a standard it would never reach again. However, Domitian's government did show signs of being totalitarian. As Emperor, he saw himself as a new Augustus. He believed he was an enlightened ruler meant to guide the Roman Empire into a new era. Using religious, military, and cultural messages, he created a strong admiration for himself. He declared three of his family members gods. He built huge structures to remember the Flavian achievements. Elaborate victory parades were held to boost his image as a warrior-emperor. But many of these were not truly earned or were too early. By naming himself "perpetual censor," he tried to control public and private morals. He started several major building projects in Rome.

He personally got involved in all parts of the government. He successfully punished corruption among public officials. The negative side of his censorial power was a limit on freedom of speech. He also became increasingly harsh towards the Roman Senate. He punished insults with exile or death. Because he was suspicious, he increasingly accepted information from informers. These informers would bring false charges of treason if needed. Despite being criticized by historians of his time, Domitian's government laid the foundation for the peaceful 2nd century. His successors, Nerva and Trajan, were less strict. But in reality, their policies were very similar to his. The Roman Empire prospered between 81 and 96 AD. Historian Theodor Mommsen described Domitian's reign as a serious but intelligent rule.

Images for kids

]

See also

In Spanish: Domiciano para niños

In Spanish: Domiciano para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |