Gnaeus Julius Agricola facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gnaeus Julius Agricola

|

|

|---|---|

A statue of Agricola erected at the Roman Baths at Bath in 1894

|

|

| Born | 13 June 40 Forum Julii, Gallia Narbonensis (now Fréjus, France) |

| Died | 23 August 93 (aged 53) Gallia Narbonensis (now Languedoc and Provence, France) |

| Allegiance | Roman Empire |

| Years of service | 58–85 |

| Rank | Proconsul |

| Commands held | Legio XX Valeria Victrix Gallia Aquitania Britannia |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Watling Street Battle of Mons Graupius |

| Awards | Ornamenta triumphalia |

Gnaeus Julius Agricola (/əˈɡrɪkələ/; born June 13, 40 – died August 23, 93) was an important Roman general and politician. He played a big part in the Roman conquest of Britain.

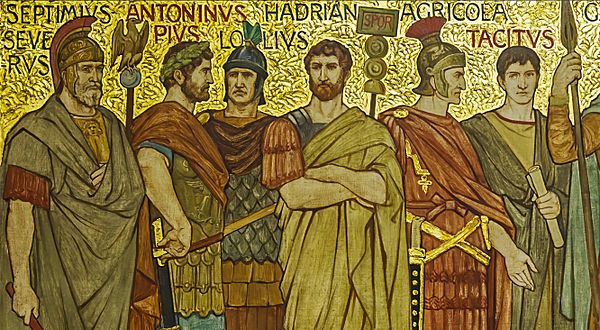

Agricola came from a powerful political family. He started his military career in Britain. Later, he held many important jobs in Rome. He became a governor in France and then in Britain. As governor of Britain, he conquered new lands. He led his army far north into Scotland. After many years of service, he retired and died in 93 AD. Most of what we know about him comes from a book written by his son-in-law, Tacitus.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Agricola was born in a Roman town called Forum Julii. This town is now Fréjus in France. His family was well-known in Roman Gaul. Both of his grandfathers were governors. His father, Lucius Julius Graecinus, was a senator. He was known for his love of philosophy.

Agricola's mother was Julia Procilla. The historian Tacitus said she was a "lady of singular virtue." She loved her son very much. Agricola went to school in Massilia (Marseille). He was very interested in philosophy.

Starting His Career

Agricola began his public life as a military officer. He served in Britain from 58 to 62 AD. He worked under Governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. He likely helped put down the Boudican rebellion in 61 AD.

In 62 AD, he returned to Rome. He married Domitia Decidiana, a noblewoman. They had a son, but he died young. Agricola became a quaestor in 64 AD. This was a financial role in the province of Asia. While there, his daughter, Julia Agricola, was born.

He continued to rise in Roman politics. In 66 AD, he became a tribune of the plebs. In 68 AD, he was made a praetor. This was an important legal and military role.

Supporting Vespasian

In 69 AD, there was a civil war in Rome. This time was known as the Year of the Four Emperors. Agricola supported Vespasian, a general who wanted to become emperor. After Vespasian became emperor, Agricola was given a high rank. He was made a patrician.

Agricola was then put in charge of the Legion XX Valeria Victrix in Britain. This legion had caused trouble for the previous governor. Agricola brought back discipline to the soldiers. He helped strengthen Roman rule in Britain. He showed his skills as a commander in battles against the Brigantes in northern England.

After his time in Britain, Agricola governed Gallia Aquitania (part of modern France). He stayed there for almost three years. In 77 AD, he returned to Rome. He became a consul, a very high political position. His daughter married Tacitus that same year. Soon after, Agricola was appointed governor of Britain for the third time.

Governor of Britain

Agricola arrived in Britain in the summer of 77 AD. He found that the Ordovices tribe in north Wales had attacked Roman cavalry. He quickly moved against them and defeated them. He then conquered Anglesey, an island off the coast of Wales. This island had been a stronghold for the native Britons.

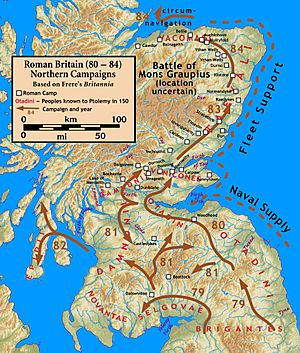

Agricola also pushed Roman rule north into Caledonia (modern Scotland). In 79 AD, he led his armies to the Firth of Tay. He built forts there. He was also a good administrator. He made fair changes to the tax system. He encouraged Britons to build towns like the Romans. He also gave Roman education to the sons of native leaders. Tacitus said this was to help make the tribes more peaceful and loyal to Rome.

Exploring Ireland

In 81 AD, Agricola crossed a body of water. He defeated people unknown to the Romans before. Tacitus doesn't say which water he crossed. Some historians think it was the Firth of Clyde or Firth of Forth. Tacitus also mentions Hibernia. This suggests Agricola might have explored southwest Scotland.

Agricola built forts along the coast facing Ireland. Tacitus wrote that Agricola believed Ireland could be conquered easily. Agricola had given shelter to an exiled Irish king. He hoped to use this king as an excuse to invade Ireland. However, this invasion never happened. Some historians think there might have been a small Roman trip to Ireland. But no Roman camps have been found there to prove it.

Interestingly, an Irish legend tells of a king named Tuathal Teachtmhar. He was exiled from Ireland as a boy. He returned from Britain with an army to claim his throne. The traditional date for his return is around 76 to 80 AD. This matches Agricola's time in Britain.

The Invasion of Scotland

The next year, Agricola used a fleet of ships. He surrounded the tribes beyond the Forth River. The Caledonians (Scottish tribes) gathered a large army against him. They attacked the Roman camp of the Ninth Legion at night. But Agricola sent in his cavalry, and the Caledonians were defeated. The Romans then pushed further north.

In the summer of 83 AD, Agricola faced the main Caledonian army. Their leader was Calgacus. This was the Battle of Mons Graupius. Tacitus said there were over 30,000 Caledonian warriors. Agricola put his auxiliary troops (non-Roman soldiers) in the front line. He kept his Roman legions in reserve. The Romans fought closely, making the Caledonians' long swords less useful.

The Caledonians were defeated. However, two-thirds of their army escaped. They hid in the Scottish Highlands. Tacitus estimated about 10,000 Caledonian casualties. The Romans lost only 360 men.

Many experts believe the battle happened in the Grampian Mountains. Some suggest sites near the Raedykes Roman camp. However, after a Roman camp was found at Durno in 1975, most scholars now think the battle took place near Bennachie in Aberdeenshire.

After his victory, Agricola took hostages from the Caledonian tribes. He might have marched his army to the northern coast of Britain. A Roman fort found at Cawdor (near Inverness) supports this idea. He also ordered his fleet to sail around the north coast. This confirmed that Britain was an island.

New Discoveries

In 2019, archaeologists found a Roman marching camp. It dates back to the 1st century AD. This camp was used by Roman legions during Agricola's invasion. The team found fire pits and ovens. These findings suggest the site was a strategic location for the Roman conquest of Ayrshire.

Later Years

Agricola was called back from Britain in 85 AD. He had been governor for an unusually long time. Tacitus claimed that Emperor Domitian recalled him. This was because Agricola's victories were greater than the emperor's own. Agricola returned to Rome quietly.

His relationship with the emperor is not fully clear. Agricola received high military honors. He was given triumphal decorations and a statue. But he never held another public or military job. He was offered the governorship of Africa, but he refused it. Tacitus suggested this was because of Domitian's actions.

Agricola died in 93 AD at his family home in France. He was 53 years old. There were rumors that Emperor Domitian poisoned him. However, there was no proof of this.

See also

In Spanish: Cneo Julio Agrícola para niños

In Spanish: Cneo Julio Agrícola para niños

Images for kids

-

A statue of Agricola erected at the Roman Baths at Bath in 1894

Sources

- Anthony Birley (1996), “Iulius Agricola, Cn.”, in Hornblower, Simon, Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Duncan B Campbell, Mons Graupius AD 83, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2010. 96pp.

- "Agricola's Campaigns", special issue of Ancient Warfare, 1/1 (2007)

- Wolfson, Stan. Tacitus, Thule and Caledonia: the achievements of Agricola's navy in their true perspective. Oxford, England: Archaeopress, 2008. 118pp. (BAR British series; 459).