Boudican revolt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Boudican revolt |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Roman conquest of Britain | |||||||

The Roman province of Britain (red), where the revolt took place. The Roman Empire is in white. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Iceni Trinovantes Other Celtic Britons |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Boudica | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 | 230,000 (Cassius Dio) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400 | 80,000 (Cassius Dio) | ||||||

The Boudican revolt was a big rebellion by the native Celtic Britons against the powerful Roman Empire. It happened around AD 60–61 in Roman Britain. The leader was Boudica, the brave Queen of the Iceni tribe. The Britons were angry because the Romans broke a promise. This promise was about who would rule the Iceni kingdom after Boudica's husband, Prasutagus, died. The Romans also treated Boudica and her daughters very unfairly.

Even though the Roman army was much smaller, their general, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, won a huge victory. This battle caused many Britons to die. We don't know exactly where this final battle took place. The Roman victory ended the main resistance to Roman rule in southern Great Britain. This Roman rule lasted until AD 410. We learn about this revolt mostly from two Roman historians, Tacitus and Dio Cassius. Their writings are the only ones we have today.

Why the Britons Rebelled

In AD 43, Rome invaded the southeastern part of Britain. The Romans took over gradually. Some native kingdoms were defeated in battles. Others stayed somewhat independent as friends of the Roman empire.

One of these tribes was the Iceni, who lived in what is now Norfolk. Their king, Prasutagus, thought he could keep his kingdom safe. He wrote a will leaving his lands to his daughters and the Roman emperor, Nero. But when he died around AD 61, the Romans ignored his will. They took over his lands completely. Roman money lenders also demanded their loans back from the Britons. This made the Iceni very angry.

First Attacks by the Rebels

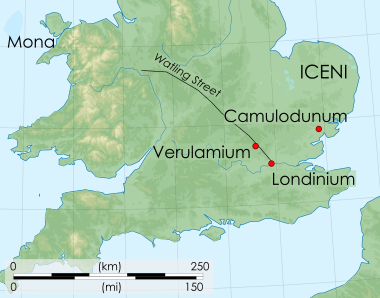

Around AD 60 or 61, the Roman governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was away. He was leading a military campaign on an island called Mona (today's Anglesey). This island was a safe place for British rebels. It was also a strong base for the druids, who were important religious leaders. While he was gone, the Iceni tribe secretly planned a revolt with their neighbors, the Trinovantes, and other tribes.

Boudica became their leader. The Roman historian Tacitus wrote that the rebels were inspired by Arminius. He was a German prince who had driven the Romans out of Germany many years before. The Britons also remembered their own ancestors who had made Julius Caesar leave Britain. Another historian, Cassius Dio, said Boudica used a special ritual. She released a hare from her clothes and watched which way it ran. She believed this would tell her if they would win. She also asked for help from Andraste, a British goddess of victory.

Tacitus imagined Boudica giving a powerful speech to her army. He wrote her saying: "I am not a noblewoman, but one of the people. I am fighting for our lost freedom. I am fighting for my body, which was whipped. I am fighting for my daughters, who were treated terribly." She ended by saying, "This is a woman's decision; as for men, they can live and be slaves."

Camulodunum: The First Target

The rebels' first target was Camulodunum (Colchester). This city used to be the capital of the Trinovantes tribe. The Romans had turned it into a colonia, a settlement for retired Roman soldiers. These soldiers were accused of treating the local people badly. Also, a huge temple to the former emperor Claudius was built there. It cost the local people a lot of money, which made them very resentful.

The Roman general Quintus Petillius Cerialis tried to help the city. He was leading the Ninth Legion. But his army was badly defeated. All his foot soldiers were killed. Only the general and some of his cavalry escaped. We don't know where this battle happened.

The Romans in the city asked for more soldiers from a Roman official named Catus Decianus. But he only sent 200 extra troops. Boudica's army attacked the city, which was not well defended. They destroyed it completely. The last Roman defenders hid in the temple for two days before it fell. Archaeologists have found proof that the city was carefully torn down. After this disaster, Catus Decianus, who had caused the uprising, ran away to Gaul.

Londinium: A Burning City

When Governor Suetonius heard about the rebellion, he rushed to Londinium. This was a new settlement built after the Roman conquest in AD 43. It had become a busy trading center with many merchants and Roman officials. Suetonius thought about fighting the rebels there. But he didn't have enough soldiers. Also, he knew about Petillius's defeat. So, he decided to leave the city to save the rest of the province. He withdrew his troops to gather more forces.

The rich citizens and traders of Londinium had already fled. They left after hearing that Catus Decianus had run away. Suetonius took with him any citizens who wanted to escape. The rest of the people were left behind. The rebels burned Londinium to the ground. They tortured and killed everyone who had not left with Suetonius.

Archaeological digs show a thick red layer of burnt material in Roman Londinium. This layer covers coins and pottery from before AD 60. Roman-era skulls found in the River Walbrook in 2013 might have been from the rebels' victims. Excavations in 1995 showed that the destruction even crossed the River Thames. It reached a suburb at the south end of London Bridge.

Verulamium: Another City Destroyed

The Roman town of Verulamium (modern St Albans) was also destroyed by the rebels. There isn't much archaeological proof for this event. Early excavations in the 1930s found little evidence. This might be because they were digging in the wrong area. Later digs in the late 1950s and early 1960s found a row of shops. These shops were along Watling Street and had been burned around AD 60. But we still don't know the full extent of the damage.

The Final Battle

Preparing for Battle

While the Britons continued their destruction, Suetonius gathered his forces. Tacitus says he brought together his own Fourteenth Legion. He also had parts of the Twentieth Legion and any available auxiliary troops. The commander of the Legio II Augusta at Isca (Exeter) did not obey orders to bring his soldiers. Still, Suetonius now had an army of almost 10,000 men.

Suetonius chose a strong position for his army. It was in a narrow valley, called a defile, with a forest behind him. The valley opened out into a wide, flat plain. His men were greatly outnumbered. Dio says that if the Roman soldiers stood in a single line, they wouldn't even stretch the length of Boudica's army. The rebel forces were said to be between 230,000 and 300,000 strong. However, modern historians think these numbers are probably too high.

The sides of the valley protected the Roman army's sides from attack. The forest behind them stopped any attacks from the rear. These defenses meant Boudica could only attack the Romans from the front. The open plain also made a surprise attack impossible. Suetonius placed his legionaries close together in the middle. He put his auxiliary infantry on the sides and his cavalry on the wings.

The Britons had a very large army. But the Iceni and other tribes had been disarmed some years before the revolt. So, they might not have had good weapons. They placed their wagons at the far end of the battlefield. Their families were in these wagons, ready to watch what they expected to be a huge victory. Some Germanic leaders had done the same thing in their battles against famous Romans like Gaius Marius and Caesar.

As the armies got ready, their leaders would have tried to inspire their soldiers. Tacitus also wrote about Suetonius speaking to his legionaries. Historians of his time often made up exciting speeches. But Suetonius's speech here is unusually direct and practical. Tacitus's father-in-law, who was a future governor, was with Suetonius at the time. He might have reported the speech quite accurately.

Boudica's Defeat

Tacitus imagined Boudica, with her daughters beside her, encouraging her troops. She gave a powerful speech from her chariot.

The numbers given for the battle in ancient writings are thought to be very exaggerated by modern historians. The Roman killing of women and animals was unusual. This is because they could have been sold for profit.

Boudica's Death

Cassius Dio says Boudica became sick, died, and was given a grand burial.

No one knows where Boudica is buried. It is probably somewhere in southern Great Britain. Modern ideas about her burial place have no strong proof. Archaeologists and historians do not agree on any location. One local story connects her to Gop Hill Cairn in Wales. Another legend says she is buried under Platform 10 of London King's Cross railway station.

What Happened After

The historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus wrote that this crisis almost made Emperor Nero give up on Britain. But since the revolt ended with a clear Roman victory, the Romans stayed in Britain. Suetonius had punished the British tribes very harshly. Nero feared this would cause more rebellions. So, he replaced Suetonius with a more forgiving governor, Publius Petronius Turpilianus.

Boudica's defeat made Roman rule stronger in southern Britain. But northern Britain remained unsettled. In AD 69, a noble from the Brigantes tribe, Venutius, led another revolt. This one was not as well documented. It started because of tribal rivalries but soon became anti-Roman.

Catus Decianus, who had fled to Gaul, was replaced by Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus. After the uprising, Suetonius carried out widespread punishments among the Britons. But Classicianus criticized this. This led to an investigation led by Nero's freed slave, Polyclitus. No historical records tell us what happened to Boudica's two daughters.

Where Was the Final Battle?

Neither of the classical historians identified the exact site of the battle. Tacitus gives a short description, but the location is still unknown. Most modern historians think it was in the Midlands. It was probably along the Roman road between Londinium and Viroconium (Wroxeter), which later became Watling Street.

An archaeologist named Graham Webster suggested a site near Manduessedum (Mancetter). This is close to the modern town of Atherstone in Warwickshire. Kevin K. Carroll suggested a place near High Cross, Leicestershire. This spot is where Watling Street and the Fosse Way meet. This location would have allowed the Legio II Augusta from Exeter to join Suetonius's forces if they had followed orders.

The area east of Rugby, Warwickshire, has also been suggested by archaeologist Jack Lucas. This is near Dow Bridge and the villages of Clifton-upon-Dunsmore and Hillmorton, south of Tripontium. Another suggested site is near Virginia Water in Surrey. This is between Callow Hill and Knowle Hill, off the Devil's Highway.

Local stories suggest "The Rampart" near Messing, Essex, and Ambresbury Banks in Epping Forest. However, these stories are not thought to be based on facts. More recently, Roman artifacts found in Kings Norton near Metchley Camp suggest another possibility. Considering Akeman Street as a possible route from the southwest, the Cuttle Mill area near Paulerspury in Northamptonshire has been suggested. Fragments of Roman pottery from the 1st century have been found there. In 2009, it was suggested that the Iceni might have been returning to their lands in Norfolk along the Icknield Way. They might have met the Roman army near Arbury Banks, Hertfordshire.

The area of King's Cross, London was once a village called Battle Bridge. This was an old crossing of the River Fleet. The name "Battle Bridge" led to a tradition that this was the site of a major battle between the Romans and Boudica's Iceni tribe. But this tradition has no historical evidence and is rejected by modern historians. Even so, Lewis Spence's 1937 book Boadicea – warrior queen of the Britons included a map showing the armies' positions there.

An 18th-century travel writer, Thomas Pennant, suggested a hill called "Bryn Paulin" in north Wales. The town of St Asaph stood on it. He thought it might be named because Paulinus and his troops camped there. A later writer, Richard Williams Morgan, was described as "patriotically fanatical." He "turned a collection of unrelated local landmarks" in this area "into the narrative of a desperate battle." He even mentioned a "Stone of the Grave of Vuddig" as proof. Boudica's last battle has also been placed on the Wyddelian road at Trelawnyd (formerly Newmarket) in Flintshire. Morien suggested that Boudica was supported by Celts who were angry about the killing of druids on Mona. He thought they moved towards the Roman force in North Wales, possibly fighting at Trelawnyd.

Relics

A bronze head was found in Suffolk in 1907. It is now in the British Museum. It was probably broken off a statue of Nero during the revolt.

Images for kids

-

The Roman province of Britain (red), where the revolt took place. The Roman Empire is in white.

-

Boadicea by Thomas Thornycroft, showing Boudica with her daughters in her chariot as she speaks to her troops before the battle.