Boudica facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Boudica |

|

|---|---|

| Queen of the Iceni | |

John Opie's Boadicea Haranguing the Britons

|

|

| Born | British Isles |

| Died | 60/61 |

| Spouse | Prasutagus |

| Issue | 2 daughters |

Boudica (also spelled Boudicca) was a powerful queen of the Iceni tribe in ancient Britain. She led a big uprising against the Roman Empire around AD 60 or 61. Even though her rebellion didn't succeed, Boudica is remembered today as a British national heroine. She stands for the fight for fairness and freedom.

Boudica's husband, Prasutagus, was a king who worked with the Romans. He had two daughters with Boudica. When he died, he wanted his kingdom to be shared between his daughters and the Roman emperor. But the Romans ignored his wishes. They took over his kingdom and all his property. Historians say the Romans also took back money they had loaned to important Britons.

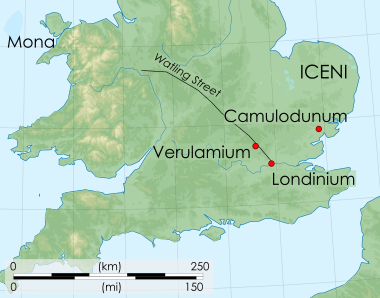

In AD 60 or 61, Boudica led the Iceni and other British tribes in a revolt. They attacked and destroyed Camulodunum, which was a Roman town for retired soldiers. When the Roman governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, heard about the revolt, he rushed to Londinium (modern London). This was a busy trading town and the rebels' next target. The governor couldn't defend Londinium, so he left it. Boudica's army then defeated a Roman army group and burned both Londinium and Verulamium (modern St Albans). It's thought that many Romans and Britons who supported them were killed by Boudica's followers. Suetonius gathered his forces and, even though he had fewer soldiers, he completely defeated the Britons. Boudica died soon after. This big rebellion made the Roman emperor Nero think about leaving Britain. But Suetonius's victory made sure the Romans stayed in control.

People became interested in Boudica's story again during the English Renaissance. She became very famous in the Victorian era and is now a strong symbol in Britain.

Contents

Who Was Boudica?

Boudica was the wife of Prasutagus, the king of the Iceni tribe. The Iceni lived in what is now Norfolk and parts of nearby counties in England. They even made some of the earliest British coins. The Iceni had rebelled against the Romans before, in AD 47. At that time, the Romans wanted to take away all weapons from the British people they controlled. After that uprising was stopped, the Romans allowed the Iceni kingdom to stay somewhat independent.

Why Did Boudica Rebel?

When King Prasutagus died in AD 60 or 61, he left his kingdom to his two daughters and the Roman Emperor Nero. But the Romans didn't respect his will. They took over the Iceni kingdom completely. The Roman official in Britain, Catus Decianus, was sent to make sure Rome controlled the Iceni lands.

The Romans then treated Boudica and her daughters very badly. They also took back money that had been loaned to the Britons. These actions made the Iceni and other tribes very angry.

Historians say Boudica gave a powerful speech to her people. In this speech, she reminded her allies, the Trinovantes, how much better life was before the Romans arrived. She said that wealth means nothing if you are enslaved. She also blamed herself for not kicking out the Romans earlier. The British people wanted their freedom more than the Roman way of life. This desire for freedom was a big reason for the rebellion.

The Great Uprising

Attacks on Roman Towns

The first place the rebels attacked was Camulodunum (modern Colchester). This was a Roman town for retired soldiers. A large Roman temple had been built there for Emperor Claudius, and the local people had to pay a lot for it. This, along with the harsh way the Roman soldiers treated the Britons, caused a lot of anger.

The Iceni and Trinovantes tribes formed a huge army. Some accounts say Boudica asked the British goddess of victory, Andraste, for help. When the revolt began, the only Roman soldiers nearby were a small group in London. They were not ready to fight Boudica's large army. Camulodunum was captured by the rebels. Those who survived the first attack hid in the Temple of Claudius for two days before they were killed.

A Roman commander, Quintus Petillius Cerialis, tried to help Camulodunum. But his army was completely defeated. Most of his foot soldiers were killed, and only he and some of his horsemen escaped. After this disaster, Catus Decianus, the Roman official who had caused the rebellion, ran away to Gaul (modern France).

The Roman governor, Suetonius, was fighting in North Wales. When he heard about the Iceni uprising, he quickly returned to deal with Boudica. He marched his men through dangerous lands to Londinium (London). He got there before Boudica's army. But because he was outnumbered, he decided to leave the town. The rebels then burned Londinium to the ground. They also attacked and destroyed Verulamium (modern St Albans).

Historians say that many people, perhaps around 80,000 Romans and Britons who supported them, were killed by the rebels. The Britons were not interested in taking prisoners.

Boudica's Defeat and Death

Suetonius gathered his remaining forces. He put together an army of about 10,000 men in a narrow valley with a forest behind them. The Romans used the land to their advantage. They threw spears at the Britons before charging forward in a wedge shape, with their cavalry (horsemen) also attacking.

Boudica's army was much larger than the Roman army. Some say it had 230,000 fighters. But Boudica's army was completely crushed. According to one historian, even the women and animals were not spared.

One account says Boudica poisoned herself after the defeat. Another says she became sick and died, and was given a grand burial. It's possible both stories are true.

What Was Her Name?

The name Boudica might have been a special title meaning 'Victorious Woman'. So, we don't know her real name. Experts believe the name Boudica comes from an old Celtic word meaning 'victorious'.

Her name has been spelled in different ways over time, like Boudicca, Bonduca, and Boadicea. The spelling Boadicea became very common in the 17th century. The poet William Cowper used this spelling in his poem Boadicea, an Ode (1782). This poem helped make Boudica famous as a British hero.

How We Know About Boudica

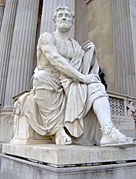

We learn about Boudica's uprising from four old Roman writings. These were written by three Roman historians: Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio.

Tacitus wrote about the rebellion many years after it happened. But his father-in-law, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, was actually in Britain during the revolt and saw some of the events.

Cassius Dio started writing his history of Rome about 140 years after Boudica died. His detailed story about Boudica only exists today because an 11th-century Byzantine monk copied parts of it. Dio's account has more dramatic details than Tacitus's, but some of his facts might not be true.

Both Tacitus and Dio wrote speeches that Boudica supposedly gave. However, it's believed her actual words were never recorded. These speeches were probably made up to show the differences between the Romans and their enemies. They also helped make Boudica a legendary figure and a symbol of patriotism.

No one described Boudica when she was alive. But Cassius Dio, writing a century later, gave a detailed description of her. He said she was "very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce, and her voice was harsh." He also said she had "a great mass of the tawniest hair" that reached her hips. She wore a large golden necklace and a colorful tunic with a thick cloak.

Boudica in Modern Times

Literature and Art

During the Renaissance, the writings of Tacitus and Cassius Dio became available in England. This changed how people saw Boudica. She appeared in historical books and plays. For example, she was called 'Voadicia' in a history by an Italian scholar.

From the 1570s to the 1590s, when England was fighting Spain, Boudica became an important symbol for the English. The poet Edmund Spenser wrote about a British heroine he called 'Bunduca'. A play called Bonduca (1612) also featured Boudica. Later, in 1695, the composer Henry Purcell set a version of this play to music. One of its songs, "Britons, Strike Home!", became a popular patriotic song in Britain.

Statues and Symbols

In the late 1700s, Boudica was used to help create ideas of English national identity. Pictures of her from this time often showed her as a classical hero, not always historically accurate.

William Cowper's 1782 poem Boadicea: An Ode was very important. It celebrated the British resistance and helped connect Boudica to ideas of British power. This poem made Boudica a British cultural icon and a national heroine. Another poem, Boädicéa (1859) by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, also drew on Cowper's work. It showed Boudica as a fierce warrior and hinted at the rise of the British Empire.

Boudica was also mentioned in many children's books in the Victorian era. For example, Beric the Briton (1893) by G. A. Henty was a novel based on the accounts of Tacitus and Dio.

The famous statue Boadicea and Her Daughters shows the queen in her war chariot. It was made by the sculptor Thomas Thornycroft between 1856 and 1871. It was placed near Westminster Bridge in London in 1902.

Boudica Today

There's a story that Boudica was buried between platforms 9 and 10 at King's Cross station in London. But there's no proof for this; it's likely a story that started after World War II.

At Colchester Town Hall, there's a life-sized statue of Boudica on the outside, made in 1902. Another image of her is in a stained glass window inside the council chamber.

Boudica was also a symbol for the suffragettes, who fought for women's right to vote. In 1908, a "Boadicea Banner" was carried in several marches. She was seen as "the eternal feminine" and "the guardian of the hearth."

Some people also see Boudica as a Celtic Welsh heroine. A statue of Boudica stands in the Marble Hall at Cardiff City Hall. It was unveiled in 1916 and shows her with her daughters, without her warrior gear.

You can find permanent exhibits about the Boudican Revolt at the Museum of London, Colchester Castle Museum, and the Verulamium Museum. There's even a 36-mile long walking path in Norfolk called Boudica's Way.

Images for kids

-

Caricature of Queen Caroline (1820)

-

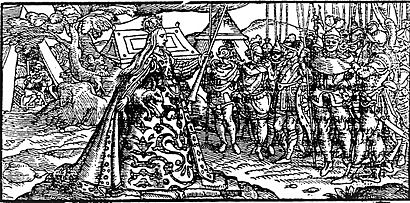

G.A. Henty, Beric, the Briton (1893)

See also

In Spanish: Boudica para niños

In Spanish: Boudica para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |