Colchester Castle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Colchester Castle |

|

|---|---|

| Colchester, Essex, England | |

Colchester Castle keep from the south, showing the main entrance

|

|

| Coordinates | 51°53′26″N 0°54′11″E / 51.890589°N 0.903047°E |

| Type | Norman castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Borough of Colchester |

| Controlled by | Colchester & Ipswich Museums |

| Condition | Keep is largely intact. |

| Site history | |

| Built | circa 1076 |

| Built by | William I of England |

| Demolished | Bailey wall and keep battlements, 17th century |

| Events | 1216 siege in the First Barons' War 1648 capture in the Siege of Colchester |

Colchester Castle is a huge Norman castle in Colchester, Essex, England. It was built in the second half of the 11th century. The main part of the castle, called the keep, is still mostly standing. It is the largest keep of its kind in all of Europe. This is because it was built on the old foundations of a Roman building called the Temple of Claudius.

The castle faced a long three-month siege in 1216. By the 1600s, it was starting to fall apart. Parts of its outer walls and upper sections were taken down. We don't know exactly how tall the castle was originally. Later, the remaining castle was used as a prison. It was also partly fixed up to be a large garden building. In 1922, the Colchester Borough Council bought the castle. Since 1860, Colchester Castle has been home to the Colchester Museum. This museum has many important Roman items on display. The castle is a special historic site and a Grade I listed building.

Contents

Building the Castle

King Henry I gave Colchester town and its castle to a man named Eudo Dapifer in 1101. This gift showed that Henry's father, William the Conqueror, and his brother, William Rufus, had also owned it. A old book called the Colchester Chronicle says Eudo started building the castle in 1076.

Some people think the castle's design is like the White Tower in the Tower of London. This is why it's sometimes linked to Gundulf of Rochester, who designed the White Tower. However, both castles also look like an even older castle in France.

Building the Main Tower (Keep)

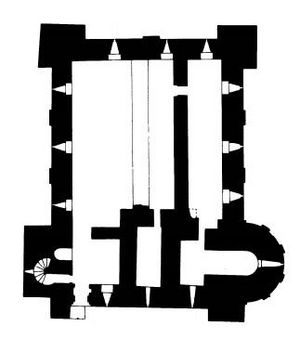

Colchester's keep is huge, measuring about 152 feet by 112 feet. This makes it the largest medieval tower ever built in Britain or Europe. Its massive size was planned because builders decided to use the stone base of the Temple of Claudius. This Roman temple was built between AD 49 and 60. It was the biggest Roman temple in Britain.

The castle site is on high ground at the west end of the walled town. When the Normans arrived, there was a Saxon chapel and other buildings nearby. These were close to the temple ruins. The Normans likely chose this spot for a few reasons. First, the Roman foundations were already there. Second, they could easily get Roman building materials. There wasn't much natural stone in the area. Also, the Normans liked to see themselves as following the Romans.

To start building, the Normans tore down what was left of the Roman temple. The castle walls were built on narrow trenches filled with rubble and mortar. They were placed right at the edge of the Roman base. The walls are made of rough stones, including septaria and Roman brick taken from nearby ruins. Smoother stones, Roman tiles, and bricks were used for decoration.

The keep originally had only one floor. You can still see parts of the battlements from this first stage on the outside walls. It seems that the partly finished castle had to be made ready for defense quickly. This might have been due to money problems or a military threat. A Danish attack in 1075 or a planned invasion in 1085 could have been the reason. Another idea is that it was only meant to be a single-story building at first.

Today, the keep has only two floors. We don't know its original height because parts were torn down in the late 1600s. For a long time, people thought it had four floors, like the White Tower. More recently, experts think it had three floors. Some of the newest studies suggest it might have always had only two floors. This idea comes from old pictures of the castle. These pictures show it looking short, not super tall. Also, it didn't take long to tear down the upper parts.

The main entrance we see today, in the southwest tower, was added later. This was during the second building phase, when the first floor and staircases were added. This second phase likely happened after 1100. It was probably done by Eudo after the 1101 charter. In the mid-1200s, a stone barbican (a fortified gate) was built near the southwest tower. This protected the main doorway.

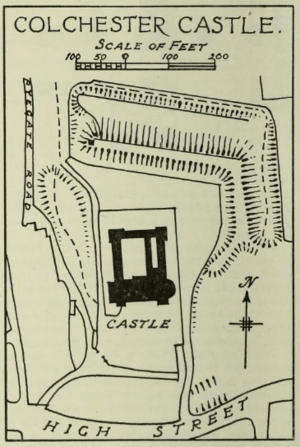

Building the Bailey

The castle's outer defenses, called the bailey, had a large earth rampart and ditch. These surrounded the keep. The northern part of this defense still exists but was changed a lot in the 1800s. Digs have shown that these earth banks were built over the remains of the Roman temple wall. The rampart to the northeast was about 28.5 meters wide and 4 meters high. The southern bank was likely finished around 1100.

Inside the bailey, an old Anglo-Saxon chapel stood near the keep. A hall was also there, southeast of the chapel. Both were kept during the first building phase of the keep. The chapel was rebuilt later, and the hall got a large fireplace.

A weaker outer bailey was made by two smaller bank-and-ditch barriers. These stretched north towards the town walls. This might be the "new bailey" mentioned in 1173. Or it could be the stone walls of the main bailey, which were in place by 1182. No trace of these stone walls has been found. This suggests they were on top of the earth rampart.

A gatehouse with two towers allowed entry to the bailey in its southwest corner. This was probably built at the same time as the bailey walls. It was reached by a bridge over the ditch. A wooden fence, part of the outer bailey defenses, blew down in 1218 and again in 1237. More repairs were needed in 1275–76.

Later History

Medieval Times

After Eudo died in 1120, the castle went back to the King. From then on, the castle was managed by people chosen by the King, called constables. Sometimes, the High Sheriff of Essex looked after it. Kings Henry I, Henry II, and Henry III all visited the castle. In 1190, 26 military tunics were bought for the castle. This shows that soldiers were living there all the time.

In 1214, William de Lanvalai was the constable. He was one of the noblemen who disagreed with King John. King John came to Colchester in November 1214. He probably tried to get Lanvalai on his side, but it didn't work. Lanvalai soon left the castle and joined other rebel noblemen. King John then sent a new constable, Stephen Harengood. Harengood was told to make the castle's defenses stronger.

The noblemen later marched on London. They made King John agree to the Magna Carta in June 1215. This agreement said Colchester Castle should go back to Lanvalai. But within months, John broke the agreement. The First Barons' War began.

John attacked Rochester Castle. Then he sent an army towards Colchester. Meanwhile, the noblemen asked King Louis VIII of France for help. French soldiers came to defend Colchester Castle for the noblemen. The siege started in January 1216. It ended in March when King John arrived. The 116 French soldiers were allowed to leave safely for London.

After Colchester was captured, Harengood became constable again. But in 1217, the castle was given to the French and the noblemen as part of a peace deal. However, the young King Henry III got it back in September 1217. This was part of the Treaty of Lambeth, which ended the war. William of Sainte-Mère-Église, the Bishop of London, then became constable.

17th and 18th Centuries

In 1607, Charles, Baron Stanhope was given charge of the castle for life. Later, in 1629, King Charles I sold the future ownership of the castle to James Hay. In 1649, a survey said the building was in bad shape. It valued the stone at only five pounds. In 1683, a man named John Wheely was allowed to tear down the castle. He planned to use the stones for other buildings in town. He caused "great devastations," tearing down much of the upper part. But he stopped when it became too expensive.

The castle has been used for many things since it stopped being a royal castle. It was a county prison. In 1645, Matthew Hopkins, who called himself the Witchfinder General, questioned and jailed people suspected of being witches there. In 1648, during the Second English Civil War, two Royalist leaders were executed behind the castle. A small stone now marks the spot where they fell. In 1656, a Quaker named James Parnell died there.

In 1727, Mary Webster bought the castle for her daughter Sarah. Sarah was married to Charles Gray, a Member of Parliament for Colchester. Gray rented out parts of the castle. He leased the main tower to a grain merchant. The east side was rented to the county as a prison. In the late 1740s, Gray fixed up parts of the building, especially the south front. He made a private park around the castle ruins. His summer house, shaped like a Roman temple, can still be seen. He also added a library with big windows. This was finished in 1760. When Gray died in 1782, the castle went to his step-grandson, James Round. He continued the restoration work.

19th and 20th Centuries

The part of the castle under the chapel stayed a prison. It was made bigger in 1801. A long-serving jailer named John Smith lived there with his family. His daughter, Mary Ann Smith, was born in the castle in 1777. She lived her whole life there and became the librarian. She died in 1852. People believe she planted the sycamore tree that still grows on top of the southwest tower. She might have planted it to celebrate the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 or to mark her father's death that same year.

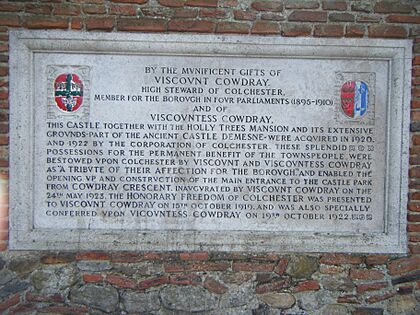

Between 1920 and 1922, the Borough of Colchester bought the castle and its parkland. A rich businessman and Member of Parliament, Viscount Cowdray, gave a large donation for this purchase. The fancy iron gates at the park entrance were made in Cheltenham. The park is now split into the Upper and Lower Castle Parks.

A museum of items owned by the borough had been on display at the castle since 1860. The main tower was roofed over in the mid-1930s. This allowed the museum to become much larger. From January 2013 to May 2014, the castle museum was greatly improved. This work cost £4.2 million. The project updated the displays with the newest information about the castle's history. It also helped repair the roof.

Images for kids

-

Colchester Castle, south front and south-east corner, showing the apse centre right