Matthew Hopkins facts for kids

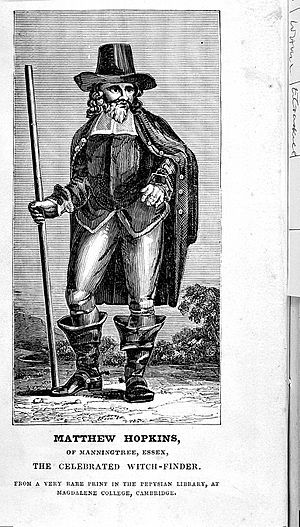

Matthew Hopkins (around 1620 – 12 August 1647) was a famous English witch-hunter. He was active during the English Civil War, a time of great conflict in England. Hopkins mostly worked in an area called East Anglia. He called himself the "Witchfinder General," but the English Parliament never officially gave him this title.

Hopkins was the son of a Puritan minister. His career as a witch-finder started in March 1644 and ended when he retired in 1647. Hopkins and his helper, John Stearne, were responsible for sending more people to be put on trial for witchcraft than all other witch-hunters in England over the previous 160 years. They caused a big increase in witch trials during those years.

Contents

Who Was Matthew Hopkins?

Very little is known about Matthew Hopkins before 1644. There are no old documents about him or his family that still exist today. He was born in Great Wenham, Suffolk. He was the fourth of six children. His father, James Hopkins, was a Puritan clergyman and a vicar at St John's Church in Great Wenham.

Matthew Hopkins was likely born after 1619. This means he was no older than 28 when he died, and possibly as young as 25. Hopkins wrote in his book, The Discovery of Witches, that he "never travelled far" to gain his experience.

In the early 1640s, Hopkins moved to Manningtree, Essex. This town is about 10 miles from Wenham. People believe Hopkins used money he inherited to become a gentleman. He also bought a place called the Thorn Inn in Mistley. Many think Hopkins was trained as a lawyer because of how he presented evidence in trials. However, there is not much proof to support this idea.

The Hunt for Witches

After some earlier witch trials, doctors were asked to examine accused women. This led to a need for physical proof that someone was a witch. Hopkins and John Stearne did not try to prove that people had done bad magic. Instead, they tried to prove that people had made a deal with the Devil.

At that time, people believed witches got their powers by choosing to work with the Devil. This made witchcraft a very serious crime against Christianity. In some laws, witchcraft was seen as such a terrible crime that normal legal rules did not apply. Since the Devil would not "confess," they needed to get a confession from the human accused.

Where They Hunted Witches

Stearne and Hopkins mainly hunted witches in East Anglia. This area included the counties of Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, and Huntingdonshire. They also worked in parts of Northamptonshire and Bedfordshire. These areas were strongly influenced by Puritans and Parliament during the English Civil War.

Hopkins wrote in his book that he started his witch-finding work in March 1644. He said he overheard women in Manningtree talking about meeting the Devil. However, John Stearne actually made the first accusations. Hopkins then became his assistant.

Twenty-three women were accused of witchcraft and put on trial in Chelmsford in 1645. Because of the Civil War, the trials were not run by regular judges. Instead, local officials led by the Earl of Warwick oversaw them. Four women died in prison, and nineteen were found guilty and put to death.

How They Made Money

Hopkins and Stearne, along with their female helpers, traveled across eastern England. They claimed that Parliament had officially asked them to find and prosecute witches. They were paid well for their work. Some people think this was a main reason for their actions.

Hopkins said his fees were to "maintain his company with three horses." He also said he took "twenty shillings a town." Records show that the town of Stowmarket paid them £23, plus travel costs. The costs to local communities were so high that in 1645, the town of Ipswich had to create a special local tax just to pay them.

Parliament knew about Hopkins' activities. Reports from the Bury St. Edmunds witch trials in 1645 showed concern. Before that trial, a report went to Parliament suggesting that "some busy men had used bad ways to force confessions." After the trials, a newspaper called the Moderate Intelligencer expressed worry about what happened in Bury.

How They Investigated

Hopkins' methods for finding witches were inspired by a book called Daemonologie, written by King James I. Hopkins often used methods like keeping people awake for a long time to get them to confess. He would also cut the arm of the accused with a dull knife. If the person did not bleed, they were said to be a witch.

Another method was the "swimming test." This was based on the idea that if witches had rejected their baptism, water would reject them. Suspects were tied to a chair and thrown into water. If they floated, they were thought to be witches. Hopkins was warned not to use this test without the person's permission. This led to the test being stopped by the end of 1645.

Hopkins and his helpers also looked for the "Devil's mark." This was believed to be a mark on witches that had no feeling and would not bleed. It was sometimes a mole or birthmark. If no visible marks were found, "witch prickers" would use knives and special needles to prick the accused, looking for hidden marks.

Facing Opposition

Hopkins and his group quickly faced opposition. One of his main opponents was John Gaule, a vicar from Great Staughton. Gaule wrote a book called Select Cases of Conscience touching Witches and Witchcrafts (1646). He also gave Sunday sermons to try and stop the witch-hunts.

In Norfolk, judges questioned Hopkins and Stearne about their methods and fees. Hopkins was asked if his ways of finding witches did not make him a witch himself. By the time this court met again in 1647, Stearne and Hopkins had retired. Hopkins went back to Manningtree.

Impact on Colonies

Hopkins' witch-hunting methods were explained in his book, The Discovery of Witches, published in 1647. These practices were even suggested in law books. After his book came out, witch trials and executions began in the New England colonies. The first person put to death was Alse Young in Connecticut in May 1647.

The next person, Margaret Jones, was accused using Hopkins' techniques of "searching" and "watching." Her execution was the start of a witch-hunt in New England that lasted from 1648 to 1663. About eighty people were accused during this time, and fifteen women and two men were put to death. Some of Hopkins' methods were also used during the famous Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts in 1692–93. These trials led to 19 executions for witchcraft.

Death and Legacy

Matthew Hopkins died at his home in Manningtree, Essex, on 12 August 1647. He likely died from a lung illness called pleural tuberculosis. He was buried just a few hours after his death in the churchyard of St Mary at Mistley Heath.

Historian Malcolm Gaskill said that Matthew Hopkins "lives on as an anti-hero and bogeyman." This means he is remembered as a bad guy in stories. Some people believed a "pleasing legend" that Hopkins was given his own swimming test and executed as a witch. However, the church records at Mistley confirm that he was buried there after dying from illness.

See also

In Spanish: Matthew Hopkins para niños

In Spanish: Matthew Hopkins para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |