Scotland in the Early Middle Ages facts for kids

Scotland in the early Middle Ages was a land of many small kingdoms. This was between about 400 CE (after the Romans left Britain) and 900 CE, when the kingdom of Alba started to grow. Four main kingdoms were important: the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, the Britons of Alt Clut, and the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia.

Later, in the late 700s, the Vikings arrived. They set up their own rulers and settlements on the islands and along the coasts. In the 800s, a family called the House of Alpin brought together the lands of the Scots and Picts. This created a single kingdom, which became the basis of the Kingdom of Scotland.

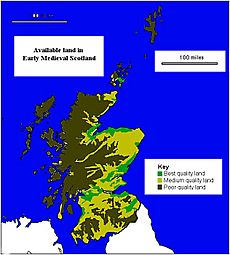

Scotland has a long coastline and lots of tough land, like mountains. During this time, the climate got colder and wetter. This meant less land was good for farming. So, not many people lived in the middle of the country or in the Highlands. There were no big cities. People lived on farms or near strongholds called brochs. They mostly grew their own food and raised animals.

Over time, the Pictish and Brythonic languages started to disappear. They were replaced by Gaelic, Scots, and later, Old Norse (the Viking language). People didn't live very long back then, so there were many young people. Society had a ruling class, freemen, and many slaves. Kings had their own groups of warriors. These groups were the main part of their armies. They would go on small raids and sometimes big campaigns.

This period also saw amazing art, like the Insular art style. Important buildings included hill forts and, later, churches and monasteries. This was also when Scottish literature began in British, Old English, Gaelic, and Latin languages.

Contents

History of Early Scottish Kingdoms

By the late 600s and early 700s, four main groups had power in northern Britain.

- In the east were the Picts. Their kingdoms eventually stretched from the River Forth to Shetland.

- In the west were the Gaelic-speaking people of Dál Riata. Their main fort was at Dunadd in Argyll. They had strong connections with Ireland. They brought the name "Scots" with them, which originally meant people from Ireland.

- In the south was the British Kingdom of Alt Clut. These people were descendants of kingdoms influenced by the Romans in "The Old North".

- Finally, there were the English or "Angles". These Germanic invaders took over much of southern Britain. They held the Kingdom of Bernicia (later part of Northumbria) in the south-east. They brought Old English with them.

The Picts: Painted People of the North

The Pictish tribes lived north of the Firth of Forth. Their lands might have reached as far as Orkney. They probably formed a group to protect themselves from the Romans to the south. The Romans first wrote about them in the late 200s. They called them picti, meaning "painted people." This might refer to their tattoos.

The first known Pictish king with wide power was Bridei mac Maelchon (ruled around 550–584). His power was based in the kingdom of Fidach, and his fort was at Craig Phadrig, near modern Inverness. After him, the Fortriu kingdom, centered in Moray and Easter Ross, became powerful. They raided along the eastern coast into what is now England. Christian missionaries from Iona started converting the Picts to Christianity around 563.

In the 600s, Bridei map Beli (671–693) became king. The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia was growing north. The Picts were likely paying tribute to them. But in 685, Bridei defeated Bernicia at the Battle of Dunnichen in Angus, killing their king, Ecgfrith.

Under Óengus mac Fergusa (729–761), the Picts were very strong. They defeated Dál Riata, invaded Alt Clut and Northumbria, and made peace treaties with the English. Later Pictish kings might have controlled Dál Riata too. For example, Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820) might have put his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riata.

Dál Riata: The Gaelic Kingdom

The Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata was on the western coast of modern Scotland. It also had some land in northern Ireland. Its main fort was probably Dunadd, near Kilmartin in Argyll and Bute. In the late 500s and early 600s, it covered much of what is now Argyll and Bute and Lochaber in Scotland, plus County Antrim in Ireland.

Many people think Dál Riata was an Irish Gaelic colony in Scotland. However, some archaeologists now disagree. The people of Dál Riata were often called Scots. This name came from the Latin word scotti, which Latin writers used for people from Ireland. Its original meaning isn't clear, but it later meant Gaelic-speakers, whether from Ireland or elsewhere.

In 563, St. Columba came from Ireland and founded the monastery of Iona off Scotland's west coast. This likely started the spread of Christianity in the area. The kingdom was strongest under Áedán mac Gabráin (ruled 574–608). But its growth was stopped at the Battle of Degsastan in 603 by Æthelfrith of Northumbria.

Big defeats in Ireland and Scotland during the time of Domnall Brecc (died 642) ended Dál Riata's best period. The kingdom then became a client of Northumbria, and later, a subject of the Picts. Historians disagree about what happened to the kingdom after the late 700s. Some believe Dál Riata got stronger again under King Áed Find (736–78), before the Vikings arrived.

Alt Clut: The British Kingdom

Alt Clut was named after the British name for Dumbarton Rock. This rock was the capital of the Strathclyde region in the Middle Ages. This kingdom might have started with the Damnonii people mentioned in Ptolemy's Geographia.

We know about two kings from this early time. The first is Ceretic, who received a letter from Saint Patrick. A writer in the 600s said Ceretic was king of Dumbarton Rock in the late 400s. Patrick's letter shows Ceretic was a Christian, and it's likely the rulers in the area were Christians too. His descendant Rhydderch Hael is mentioned in Adomnán's Life of Saint Columba.

After 600, we have more information about the Britons of Alt Clut. In 642, led by Eugein, they defeated Dál Riata and killed Domnall Brecc at Strathcarron. The kingdom was attacked several times by the Picts under Óengus, and later by the Picts' allies from Northumbria, between 744 and 756. They lost the Kyle region in southwest Scotland to Northumbria. The last attack might have forced King Dumnagual III to give in to his neighbors.

After this, we hear little about Alt Clut until it was burned and likely destroyed in 780. We don't know who did it or why. Historians used to think Alt Clut was the same as the later Kingdom of Strathclyde. But some, like J. E. Fraser, point out there's no proof that Alt Clut's main area was in Clydesdale. So, the Kingdom of Strathclyde might have appeared after Alt Clut declined.

Bernicia: The Anglian Kingdom

The British kingdoms in what is now the border region between England and Scotland are called Yr Hen Ogledd ("The Old North") by Welsh scholars. This included Bryneich, which might have had its capital at modern Bamburgh in Northumberland. It also included Gododdin, centered at Din Eidyn (now Edinburgh) and stretching across modern Lothian.

Some "Angles" might have worked as soldiers along Hadrian's Wall during the late Roman period. Others are thought to have moved north by sea from Deira in the early 500s. At some point, the Angles took control of Bryneich, which became the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia. The first Anglo-Saxon king in history was Ida, who became king around 547. Around 600, the Gododdin gathered about 300 men to attack the Anglo-Saxon fort of Catraeth, perhaps Catterick, North Yorkshire. This battle was a disaster for the Britons and is remembered in the poem Y Gododdin.

Ida's grandson, Æthelfrith, joined Deira with his own kingdom, forming Northumbria around 604. Æthelfrith's son later ruled both kingdoms after Æthelfrith was defeated and killed in 616. He likely brought Christianity with him, as he had converted while in exile. After his defeat and death in 633, Northumbria was again split into two kingdoms under pagan kings.

Oswald (ruled 634–42), another son of Æthelfrith, defeated the Welsh. He seems to have been accepted as king of a united Northumbria by both Bernicians and Deirans. He had become Christian while in exile in Dál Riata. He looked to Iona for missionaries, not Canterbury. The island monastery of Lindisfarne was founded in 635 by the Irish monk Saint Aidan. It became the main church center for Northumbria. In 638, Edinburgh was attacked by the English. Around this time, or soon after, the Gododdin lands in Lothian and around Stirling came under Bernicia's rule.

After Oswald died fighting the Mercians, the two kingdoms split again. But from this point, the English kings were Christian. After the Synod of Whitby in 664, the Northumbrian kings accepted the leadership of Canterbury and Rome. In the late 600s, the Northumbrians expanded north of the Forth. But they were defeated by the Picts at the Battle of Nechtansmere in 685.

Vikings Arrive and the Kingdom of Alba Begins

The balance of power between the kingdoms changed in 793. Fierce Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona and Lindisfarne. This caused great fear and confusion across northern Britain. Orkney, Shetland, and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen. The king of Fortriu, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the king of Dál Riata, Áed mac Boanta, died after a big defeat by the Vikings in 839.

A mix of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlers in southwest Scotland created the Gall-Gaidel, or Norse Irish. This is where the region of Galloway gets its name today. Sometime in the 800s, the struggling kingdom of Dál Riata lost the Hebrides to the Vikings. Ketil Flatnose is said to have founded the Kingdom of the Isles.

These threats might have sped up a long process of the Pictish kingdoms becoming more Gaelic. They adopted Gaelic language and customs. The Gaelic and Pictish crowns also merged. Historians debate whether the Picts took over Dál Riata, or if it was the other way around. This led to the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s. He brought the House of Alpin to power as leaders of a combined Gaelic-Pictish kingdom. In 867, the Vikings took Northumbria, forming the Kingdom of York. Three years later, they attacked the Briton fort of Dumbarton. They then conquered much of England, except for a smaller Kingdom of Wessex. This left the new combined Pictish and Gaelic kingdom almost surrounded.

The first kings after Cináed were called King of the Picts or King of Fortriu. They were removed from power in 878 when Áed mac Cináeda was killed by Giric mac Dúngail. But they returned after Giric's death in 889. When Cináed's later successor Domnall mac Causantín died at Dunnottar in 900, he was the first to be called rí Alban (meaning King of Alba). This new name in the Gaelic records is sometimes seen as the birth of Scotland. But there's nothing from his reign to confirm this. His kingdom, known as "Alba" in Gaelic, "Scotia" in Latin, and "Scotland" in English, was the core from which the Scottish kingdom would grow as Viking power faded. This was similar to how the Kingdom of Wessex in the south grew to become the Kingdom of England.

Scotland's Geography

Land and Landscape

Modern Scotland is about half the size of England and Wales. But with its many inlets, islands, and inland lochs (lakes), it has about the same amount of coastline, around 4,000 miles. Only one-fifth of Scotland is less than 60 meters (about 200 feet) above sea level. Its location on the east Atlantic means it gets a lot of rain, especially in the west. This led to widespread peat bogs. The acidic soil, strong winds, and salt spray made most islands treeless.

Hills, mountains, quicksands, and marshes made travel and conquest very hard. This might have caused political power to be split into many small areas. The early Middle Ages had a colder and wetter climate. This meant more land became unproductive.

Where People Lived

Roman influence north of Hadrian's Wall didn't change how people settled much. Iron Age hill forts and forts on headlands continued to be used. These often had defenses made of dry stone or timber walls, sometimes with a palisade. The large number of these forts suggests that kings and nobles moved around their lands to control them. In the Northern and Western Isles, Iron Age Brochs and wheel houses were still used. But they were slowly replaced by simpler cellular houses.

There are a few large timber halls in the south, similar to those found in Anglo-Saxon England from the 600s. In areas where Vikings settled, like the islands and coast, there wasn't much timber. So, people used local materials like stone and turf to build houses.

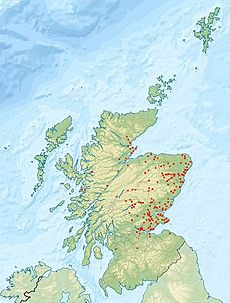

Place names, especially those starting with "pit" (meaning land or field), suggest that most Picts lived in modern Fife, Perthshire, Angus, Aberdeen, and around the Moray Firth. However, later Gaelic migration might have removed some Pictish names. Early Gaelic settlements seem to have been in western Scotland, between Cowal and Ardnamurchan, and the nearby islands. They later spread up the West coast in the 700s.

There is evidence of Anglian settlement in southeast Scotland, reaching into West Lothian. There was also some settlement in southwest Scotland. Later Norse (Viking) settlement was probably largest in Orkney and Shetland. There was less settlement in the western islands, especially the Hebrides, and on the mainland in Caithness. It stretched along fertile river valleys through Sutherland and into Ross. There was also a lot of Viking settlement in Bernicia, the northern part of Northumbria, which reached into the modern Borders and Lowlands.

Languages Spoken

This time period saw big changes in languages. Modern language experts divide Celtic languages into two main groups:

- P-Celtic: This group includes Welsh, Breton, and Cornish.

- Q-Celtic: This group includes Irish, Manx, and Gaelic.

The Pictish language is still a mystery. The Picts didn't have their own writing system. All that's left are place names and a few inscriptions in Irish ogham script. Most modern linguists agree that Pictish belonged to the P-Celtic group, even though its exact nature is unclear. Historical records and place names show how Pictish in the north and Cumbric in the south were replaced by Gaelic, English, and later Norse during this period.

Economy and Daily Life

Unlike other parts of Britain that had Roman cities, Scotland's economy in the early Middle Ages was mostly based on farming. Without good transport links or large markets, most farms had to produce all their own food. This included meat, dairy products, and grains. People also gathered food and hunted.

Archaeological finds show that farming in northern Britain was done around a single farm or a small group of three or four homes. Each home probably had a small family. Neighbors were likely related, sharing land through inheritance. Farming used a system with an "infield" close to the settlement where crops were grown every year. There was also an "outfield" further away, where crops were grown some years and left empty (fallow) in others. This system continued until the 1700s.

Bones found show that cattle were the most important farm animal, followed by pigs, sheep, and goats. Domesticated fowl (like chickens) were rare. Imported goods found at archaeological sites include pottery and glass. Many sites also show that people worked with iron and precious metals.

Population and Society

We have very few written records to figure out how many people lived in early Medieval Scotland. Estimates suggest about 10,000 people in Dál Riata and 80,000–100,000 in Pictland. The 400s and 500s likely saw more deaths due to the bubonic plague, which might have reduced the population.

It's thought that society had high birth rates and high death rates. This is similar to many developing countries today. The population was relatively young, with people having children early and many children per woman. This meant there were fewer workers compared to the number of people who needed to be fed. This made it hard to produce extra food, which would have allowed the population to grow and more complex societies to develop.

Social Structure

The main way society was organized in Germanic and Celtic Europe was through family groups (kin groups). Later records mention that Pictish ruling families passed power through the female line. Also, leaders from outside Pictish society sometimes appeared. This led to the idea that their system of passing power was matrilineal (through the mother's side). However, some historians disagree. They argue that there is clear evidence of knowing descent through the male line. This suggests it was more likely a bilateral system, where descent was counted through both male and female lines.

Some evidence, like records in Irish writings and images of warriors on Pictish stone slabs (like at Aberlemno and Hilton of Cadboll), suggests that society in northern Britain was led by a military noble class. Their status depended a lot on their ability and willingness to fight. Below the nobles were likely non-noble freemen. They worked their own small farms or rented land. No law codes from Scotland survive from this period. But laws in Ireland and Wales show that freemen could carry weapons, speak for themselves in court, and receive payment if a relative was murdered.

Records suggest that society in North Britain had many slaves. Slaves were often taken during wars and raids, or bought. St. Patrick mentioned that the Picts were buying slaves from the Britons in Southern Scotland. Slavery probably reached quite low in society, with most rural homes having some slaves. Because they were often taken young and looked similar to their owners, many slaves became more integrated into their new societies. They might have adopted the culture and language of their captors. Living and working with their owners, they might have become part of the household. In places where there is more evidence, like England, it was common for slaves who lived to middle age to gain their freedom. These freed people often remained connected to their former masters' families.

Kingship and Power

In the early Middle Ages, kingship in Britain wasn't passed directly from father to son, as it would be later. Instead, there were several people who could become king. They usually had to be part of a certain family and claim to be descended from a specific ancestor. Kingship could be complex and change often.

The Pictish kings of Fortriu likely acted as overlords (more powerful rulers) over other Pictish kings for much of this time. Sometimes, they could even control non-Pictish kings. But sometimes, they themselves had to accept the rule of outside leaders, both Anglian and British. These relationships might have meant paying tribute or providing soldiers. After a victory, lesser kings might have received rewards for their service. Marrying into the ruling families of smaller kingdoms might have led to these kingdoms being absorbed. Even though these mergers could sometimes be undone, it seems that kingship was slowly becoming controlled by a few of the most powerful families.

The king's main job was to be a war leader. This is why very few kings were children or women during this period. Kings organized the defense of their people's lands, property, and lives. They also negotiated with other kings to keep their people safe. If they failed, settlements might be raided, destroyed, or taken over, and people killed or enslaved. Kings also engaged in small-scale raiding and bigger wars with large armies and alliances. These wars could happen over long distances, like Dál Riata's trip to Orkney in 581 or the Northumbrian attack on Ireland in 684.

Kingship also had special ceremonies. The kings of Dál Riata were crowned by putting their foot in a footprint carved in stone. This meant they would follow in the footsteps of the kings before them. The kings of the united kingdom of Alba had Scone and its sacred stone at the heart of their coronation ceremony. Historians believe this tradition came from Pictish practices. Iona, an early center of Scottish Christianity, was where early Scottish kings were buried until the 1000s. Then, the House of Canmore chose Dunfermline, which was closer to Scone.

Warfare and Armies

A king's power mainly came from his bodyguard or war-band. In the British language, this was called the teulu. In Latin, it was often tutores, meaning "defend, preserve from danger." The war-band acted as an extension of the ruler's power. It was the core of larger armies that were sometimes gathered for big campaigns.

In peaceful times, the war-band spent time in the "Great Hall." Here, in both Germanic and Celtic cultures, they would feast, drink, and bond. This kept the war-band strong. In the epic poem Beowulf, the war-band slept in the Great Hall after the lord went to his room. It's unlikely that any war-band in this period had more than 120–150 men. No hall big enough for more has been found in northern Britain.

Pictish stones, like the one at Aberlemno in Angus, show mounted and foot warriors. They have swords, spears, bows, helmets, and shields. The many hill forts in Scotland might have made open battles less important than in Anglo-Saxon England. The fact that many kings died in fires or by drowning suggests that sieges (surrounding a fort to capture it) were a more important part of warfare in northern Britain.

Sea power was also important. Irish records mention a Pictish attack on Orkney in 682, which must have needed a large navy. They also lost 150 ships in a disaster in 729. Ships were vital for fighting in the Highlands and Islands. From the 600s, the Senchus fer n-Alban shows that Dál Riata had a system where groups of households had to provide 177 ships and 2,478 men. The same source mentions the first recorded naval battle around the British Isles in 719. It also lists eight naval expeditions between 568 and 733.

The only boats that survive from this time are dugout canoes. But images from the period suggest there might have been skin boats (like the Irish currach) and larger boats with oars. The Viking raids and invasions used their superior sea power. Their success came from their fast, light, wooden boats with shallow bottoms. These boats could travel in water only 3 feet deep and land on beaches. Their light weight also meant they could be carried over land (portages). Longships were also pointed at both ends, allowing them to change direction quickly without turning around.

Religion in Early Scotland

Old Religions (Before Christianity)

Very little is known about religion in Scotland before Christianity arrived. Since the Picts didn't have their own written records, we can only guess from other places, a few archaeological finds, and negative accounts from later Christian writers. It's generally thought to have been similar to Celtic polytheism (worshipping many gods).

More than 200 Celtic gods have been named. Some, like Lugh, The Dagda, and The Morrigan, come from later Irish stories. Others, like Teutatis, Taranis, and Cernunnos, come from evidence in Gaul (modern France). Celtic pagans built temples and shrines to honor these gods. They did this through votive offerings (gifts) and sacrifices, possibly including human sacrifice. According to Greek and Roman accounts, in Gaul, Britain, and Ireland, there was a priestly group called the druids. However, very little is truly known about them. Irish legends about the Picts and stories about St. Ninian connect the Picts with druids. The Picts are also linked to "demon" worship. One story about St Columba tells of him removing a demon from a well in Pictland. This suggests that worshipping well spirits was part of Pictish paganism. Roman mentions of the goddess Minerva being worshipped at wells, and a Pictish stone near a well at Dunvegan Castle on Skye, support this idea.

How Christianity Began

Christianity in Scotland probably started with Roman soldiers, like Saint Kessog (son of the king of Cashel), and ordinary Roman citizens near Hadrian's Wall. Archaeology from the Roman period shows that the northern parts of the Roman province of Britannia were among the most Christianized areas on the island. Chi-Rho symbols (early Christian symbols) and Christian grave-slabs have been found on the wall from the 300s. Around the same time, Mithraic shrines (called Mithraea) along Hadrian's Wall were attacked and destroyed, likely by Christians.

After the Romans left, it's generally believed that Christianity survived among the British groups like Strathclyde. But it likely faded as the pagan Anglo-Saxons moved in. The Anglo-Saxons worshipped gods like Tiw, Woden, Thor, and Frig, whose names are still used for days of the week. They also worshipped Eostre, whose name was used for the spring festival of Easter. While British Christians continued to bury their dead without grave goods, pagan Anglo-Saxons can be seen in archaeological records by their practice of cremation and burial in urns, with many grave goods. These goods were perhaps meant to go with the dead to the afterlife. However, despite growing evidence of Anglian settlement in southern Scotland, only one such grave has been found, at Dalmeny in East Lothian.

The spread of Christianity in Scotland has traditionally been seen as depending on Irish-Scots "Celtic" missionaries. It also came, to a lesser extent, from Rome and England. Celtic Christianity started with the conversion of Ireland from late Roman Britain, linked to St. Patrick in the 400s. In the 500s, monks sent by St Patrick, like St Kessog, founded monasteries. St Kessog's abbey was halfway between Glasgow and Edinburgh. Soon after, St. Columba, also Irish, founded Iona abbey. Both were martyrs. Later monk missionaries from Ireland worked on the British mainland, spreading a shared culture.

St Ninian is linked to a monastery founded at Whithorn in what is now Galloway. However, many believe Ninian might be a later story. St Columba left Ireland and founded the monastery at Iona off the West Coast of Scotland in 563. From there, he carried out missions to the Scots of Dál Riata and the Picts. It seems likely that both the Scots and Picts had already started to become Christian before this time. Saint Patrick mentioned "apostate Picts" in a letter, suggesting they had been Christian before. The poem Y Gododdin, set in the early 500s, doesn't describe the Picts as pagans. The conversion of the Pictish leaders likely took a long time, starting in the 400s and not finishing until the 600s.

Key signs of Christianization include long-cist cemeteries. These usually mean Christian burials because they are oriented east-west, though this idea has been questioned recently. These burials are found from the end of the Roman era to the 600s, after which they become rarer. They are mostly in eastern Scotland south of the Tay, in Angus, the Mearns, Lothian, and the Borders. Scholars generally agree that the place-name element eccles-, from the British word for church, shows evidence of the British church from the Roman and immediate post-Roman period. Most of these names are in the southwest, south, and east. About a dozen inscribed stones from the 400s and 500s, starting with the Latinus stone of Whithorn (around 450), show Christianity through their dedications. These stones are spread across southern Scotland.

Celtic Christianity's Unique Style

Celtic Christianity was different from the Roman style in some ways. The most important differences were how Easter was calculated and the method of tonsure (shaving hair for monks). But there were also differences in how priests were ordained, how people were baptized, and in church services.

Celtic Christianity was heavily based on monasteries. These monasteries were very different from those on the European continent. They were often isolated groups of wooden huts surrounded by a wall. Because much of the Celtic world didn't have cities like the Roman world, bishoprics (areas led by a bishop) were often connected to abbeys.

In the 400s, 500s, and 600s, Irish monks set up monasteries in parts of modern-day Scotland. Monks from Iona, led by St. Aidan, then founded the See of Lindisfarne in Anglian Northumbria. The part of southern Scotland ruled by the Anglians at this time had a Bishopric at Abercorn in West Lothian. It's thought that it adopted Rome's leadership after the Synod of Whitby in 663. This lasted until the Battle of Dunnichen in 685, when the Bishop and his followers were forced out. By this time, the Roman way of calculating Easter and other changes had already been adopted in much of Ireland. The Picts accepted Rome's changes under Nechtan mac Der-Ilei around 710. Followers of Celtic traditions moved to Iona and then to Innishbofin. The Western Isles remained a place of Celtic practice for some time. Celtic Christianity continued to influence religion in England and across Europe into the late Middle Ages. It spread Christianity, monasteries, art, and religious ideas across the continent.

Viking Paganism and Conversion

When the Vikings took over the islands and coastal regions of modern Scotland, pagan worship returned to those areas. Norse paganism had some of the same gods that the Anglo-Saxons had worshipped before they became Christian. It was thought to focus on different cults, involving gods, ancestors, and spirits. Calendar and life cycle rituals often included sacrifices. The pagan beliefs of the ruling Norse elite can be seen in goods found in 900s graves in Shetland, Orkney, and Caithness.

There is no record from that time about how the Vikings in Scotland became Christian. Historians have traditionally said that Viking settlements in Britain converted to Christianity in the late 900s. Later stories say that Viking earls accepted Christianity. However, there is evidence that conversion had started before this. There are many islands called Pabbay or Papa in the Western and Northern Isles. These names might mean "hermit's" or "priest's isle" from this period. Changes in grave goods and Viking place names using "-kirk" (meaning church) also suggest that Christianity had started to spread before it was officially accepted by Viking leaders. Later documents suggest there was a Bishop working in Orkney in the mid-800s. More recently found archaeological evidence, including Christian symbols like stone crosses, suggests that Christian practice might have survived the Viking takeover in parts of Orkney and Shetland. It also suggests that the conversion process might have begun before Christianity was officially accepted by Viking leaders. The continuation of Scottish Christianity might also explain how quickly Norse settlers later adopted the religion.

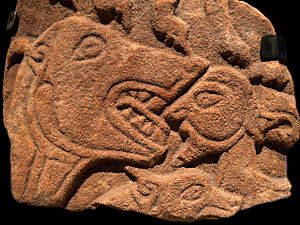

Art and Creativity

From the 400s to the mid-800s, Pictish art is mostly known through stone sculptures. There are also a smaller number of very high-quality metalwork pieces. After the Picts converted to Christianity and their culture mixed with that of the Scots and Angles, elements of Pictish art became part of the style known as Insular art. This style was common across Britain and Ireland. It became very influential in Europe and helped develop Romanesque styles.

Pictish Stones: Carved Stories

About 250 Pictish stones still exist. Scholars have put them into three groups:

- Class I stones: These are thought to be from up to the 600s and are the most common. They are mostly unshaped stones with carved symbols of animals (like fish and the Pictish beast), everyday objects (like mirrors, combs, and tuning forks), and abstract symbols. They are found from the Firth of Forth to Shetland. The most are in Sutherland, around modern Inverness and Aberdeen. Good examples include the Dunrobin (Sutherland) and Aberlemno stones (Angus).

- Class II stones: These are carefully shaped slabs from after Christianity arrived in the 700s and 800s. They have a cross on one side and many symbols on the other. There are fewer of these than Class I stones. They are mostly found in southern Pictland, in Perth, Angus, and Fife. Good examples include Glamis 2, which has a beautifully carved Celtic cross with two figures, a centaur, a cauldron, a deer head, and a triple disc symbol. Cossans, Angus, shows a Pictish boat with oarsmen and a figure at the front.

- Class III stones: These are thought to be from the same time as Class II stones. Most are elaborately shaped and carved cross-slabs. Some have scenes with people, but they don't have the unique Pictish symbols. They are found widely but are most common in the southern Pictish areas.

Pictish Metalwork: Shiny Treasures

Metalwork has been found throughout Pictland. The Picts seem to have had a lot of silver. This probably came from raiding further south or from payments to stop them from raiding. The very large collection of late Roman hacksilver (cut-up silver) found at Traprain Law might have come from either source. The largest collection of early Pictish metalwork was found in 1819 at Norrie's Law in Fife. Sadly, much of it was scattered and melted down.

Over ten heavy silver chains, some more than 0.5 meters (about 1.6 feet) long, have been found from this period. The double-linked Whitecleuch Chain is one of only two that has a circular ring. It has symbol decoration, including enamel, which shows how these were probably used as "choker" necklaces. The St Ninian's Isle Treasure has perhaps the best collection of Pictish art forms.

Irish-Scots Art: Blending Styles

The kingdom of Dál Riata was a place where Pictish and Irish art styles mixed. The Scots settlers in what is now Argyll kept close contact with Ireland. This can be seen in finds from excavations of the fort of Dunadd, which combine Pictish and Irish elements. This included a lot of evidence for making high-quality jewelry. Molds from the 600s show that pieces similar to the Hunterston brooch, found in Ayrshire, were made. These pieces also had elements that suggest Irish origins. These and other finds, like a trumpet spiral decorated hanging bowl disc and a stamped animal decoration, show how Dál Riata was one of the places where the Insular style developed. In the 700s and 800s, the Pictish nobles adopted true penannular brooches (circular brooches with a gap) with rounded ends from Ireland. Some older Irish pseudo-penannular brooches were changed to the Pictish style, for example, the Breadalbane Brooch (British Museum). The 700s Monymusk Reliquary has elements of both Pictish and Irish styles.

Insular art, also called Hiberno-Saxon art, is the name for the common art style made in Scotland, Britain, and Anglo-Saxon England from the 600s. It combined Celtic and Anglo-Saxon forms. Surviving examples of Insular art are found in metalwork, carvings, but mainly in illuminated manuscripts (decorated books). Surfaces are highly decorated with complex patterns. There is no attempt to show depth or volume.

The best examples include the Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels, and Book of Durrow. Carpet pages (pages filled entirely with decoration) are a special feature of Insular manuscripts. Also common are historiated initials (decorated first letters of a paragraph, an Insular invention), canon tables (lists of parallel passages in the Gospels), and pictures, especially Evangelist portraits (pictures of the writers of the Gospels). The best period of this style ended when Viking raids in the late 700s disrupted monasteries and noble life. The influence of Insular art affected all later European Medieval art, especially the decorations in Romanesque and Gothic manuscripts.

Buildings and Architecture

After the Romans left, new forts were built. These were often smaller, "nucleated" (clustered) buildings compared to those from the Iron Age. They sometimes used important natural features, like at Edinburgh and Dunbarton. All the northern British peoples used different types of forts. The type of fort built depended on the local land, building materials, and military needs. The first known king of the Picts, Bridei mac Maelchon, had his base at the fort of Craig Phadrig near modern Inverness. The Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata was probably ruled from the fortress of Dunadd near Kilmartin in Argyll and Bute.

Christianity came to Scotland from Ireland starting in the 500s. This led to the building of the first churches. These might have been made of wood at first, like the one found at Whithorn. But most churches from this time that we have evidence for are simple stone buildings. They started on the west coast and islands and spread south and east.

Early chapels often had square-ended walls that came together, similar to Irish chapels of this time. Medieval parish churches in Scotland were usually much simpler than in England. Many churches remained simple rectangles, without transepts (cross-arms) or aisles, and often without towers. In the Highlands, they were even simpler. Many were built of rough stone and sometimes looked like houses or farm buildings from the outside.

Monasteries also differed greatly from those on the continent. They were often isolated groups of wooden huts surrounded by a wall. At Eileach an Naoimh in the Inner Hebrides, there are huts, a chapel, a refectory (dining hall), a guest house, barns, and other buildings. Most of these were made of timber and wattle (woven branches) and probably had roofs of heather and turf. They were later rebuilt in stone, with underground cells and circular "beehive" huts like those used in Ireland. Similar sites have been found on Bute, Orkney, and Shetland. From the 700s, more complex buildings started to appear.

Literature and Stories

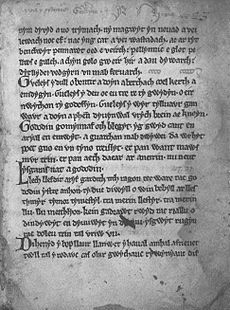

Much of the earliest Welsh literature was actually written in or near what is now Scotland. However, it was only written down in Wales much later. This includes The Gododdin, which is thought to be the oldest surviving poem from Scotland. It is credited to the bard Aneirin, who is said to have lived in Gododdin in the 500s. Another work is the Battle of Gwen Ystrad, credited to Taliesin, who was traditionally a bard at the court of Rheged around the same time.

There are also religious works in Gaelic. These include the Elegy for St Columba by Dallan Forgaill (around 597) and "In Praise of St Columba" by Beccan mac Luigdech of Rum (around 677). In Latin, there is a "Prayer for Protection" (said to be by St Mugint) (around mid-500s) and Altus Prosator ("The High Creator," said to be by St Columba) (around 597). In Old English, there is The Dream of the Rood. Lines from this poem are found on the Ruthwell Cross. This makes it the only surviving piece of Northumbrian Old English from early Medieval Scotland.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |