Christianity in Medieval Scotland facts for kids

Christianity arrived in what is now Lowland Scotland a long time ago, probably with Roman soldiers. After the Romans left in the 400s, Christianity likely continued among the British people in the south. However, as pagan Anglo-Saxons moved in, Christianity became less common in some areas.

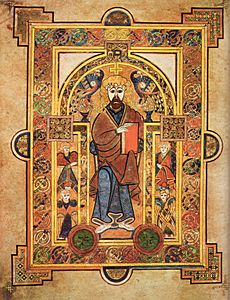

Scotland was mostly converted to Christianity by missionaries from Ireland between the 400s and 600s. Important figures like St Columba helped set up monasteries and churches that served large regions. This early form of Christianity, sometimes called "Celtic Christianity", had some differences from the Roman Church. For example, abbots (heads of monasteries) were often more important than bishops, and rules about priests marrying were more relaxed. There were also differences in how Easter was calculated and how priests shaved their heads. Most of these differences were sorted out by the mid-600s.

After the Vikings in northern Scotland became Christian in the 900s, the Roman Catholic Church became the main religion. In the Norman period (1000s to 1200s), the Scottish Church changed a lot. With support from kings and nobles, a clearer system of local churches (parishes) developed. Many new monasteries were built, following new rules from Europe. The Scottish Church also became more independent from England. It developed its own system of dioceses (areas managed by bishops) and was called a "special daughter of the see of Rome," meaning it reported directly to the Pope. However, it didn't have its own Archbishops yet.

In the late Middle Ages, problems in the Catholic Church, like the Western Schism (when there were two or more Popes), allowed the Scottish kings to have more say in who became important church leaders. By the late 1400s, Scotland finally had two archbishoprics (areas led by archbishops). While traditional monastic life seemed to decline, new groups of friars, who focused on preaching and helping people, became very popular, especially in growing towns. New saints and ways of showing devotion also became common. Despite issues with the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the 1300s, and some new ideas (called heresy) in the 1400s, the Church in Scotland stayed strong until the Scottish Reformation in the 1500s.

Contents

Early Christianity in Scotland

How Christianity Began

Before the Middle Ages, most people in what is now Scotland followed old Celtic religions. But signs of Christian symbols and the destruction of other religious sites suggest that the Romans brought Christianity to the northern part of their province, Britannia. From there, it might have spread to parts of Caledonia (roughly modern Scotland).

After the Roman Empire lost control in the early 400s, four main groups lived in northern Britain:

- The Picts in the east, whose kingdoms stretched from the River Forth to Shetland.

- The Gaelic-speaking people of Dál Riata in the west, who came from Ireland and brought the name "Scots" with them.

- The British people in the south, descendants of those in Roman-influenced kingdoms like Kingdom of Strathclyde.

- The English or "Angles," Germanic invaders who took over much of southern Britain and parts of what is now southeast Scotland.

While the Picts and Scots were likely still pagan, many experts believe Christianity survived among the British people after the Romans left. However, it became less common as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced.

Christianity spread in Scotland mostly through Irish-Scots missionaries, and to a lesser extent, from Rome and England. In the 500s, missionaries from Ireland were active on the British mainland. This movement is linked to figures like St Columba. St Columba probably learned from another saint, Finnian. He left Ireland and founded a monastery on the island of Iona in 563. From Iona, missions went to western Argyll and the islands around Mull. Later, Iona's influence reached the Hebrides. In the 600s, St. Aidan went from Iona to start a church at Lindisfarne off the coast of Northumbria (now northeast England). Lindisfarne's influence then spread into what is now southeast Scotland. This created many overlapping churches. Iona became the most important religious center, partly thanks to Adomnan, who was its abbot from 679 to 704. Adomnan's book, Life of St. Columba, made Columba famous as the "apostle" (main missionary) of northern Britain.

It's not fully clear how or how quickly the Picts became Christian. It might have started early. For example, St. Patrick, active in the 400s, mentioned "apostate Picts" in a letter, suggesting they had been Christian before. Also, an old poem called Y Gododdin, set in the early 500s, doesn't describe the Picts as pagans. It seems the Pictish leaders slowly converted over a long time, from the 400s to the 600s, and the general population might have taken until the 700s.

Signs of Christianisation include cemeteries with long stone graves, usually facing east-west. These cemeteries are thought to be Christian because they are near churches or have Christian writings. They are found from the early 400s to the 1100s, mostly in eastern Scotland south of the River Tay. Many experts agree that place names starting with eccles- (from a British word for church) show where British churches were in Roman and post-Roman times. Most of these are in southern Scotland. From the 400s and 500s, carved stones with Christian messages are found across southern Scotland. The earliest is the Latinus stone from Whithorn, around 450 AD. In the east and north, Pictish stones began to show Christian symbols from the early 700s.

Early churches were probably made of wood, like one found at Whithorn. But surviving evidence shows simple stone churches, starting on the west coast and islands, then spreading south and east. Early chapels often had square ends and narrowing walls, similar to Irish chapels. Medieval parish churches in Scotland were usually simpler than in England. Many were just long rectangular buildings, without side sections or towers. In the Highlands, they were even simpler, often made of rough stone and looking like houses or farm buildings from the outside.

Celtic Christianity Explained

"Celtic Church" is a term used by experts to describe a specific type of Christianity that started in Ireland, linked to St. Patrick. This form later spread to northern Britain through Iona. It also describes the Christian setup in northern Britain before the 1100s, when new religious ideas from France began to take hold in Scotland. Celtic Christianity is often compared to the Roman form, which arrived in southern England in 587 with St. Augustine of Canterbury. Later missions from Canterbury helped convert the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, reaching Northumbria in the early 700s, where Iona already had an influence. So, Christianity in Northumbria became a mix of Celtic and Roman ideas.

While Roman and Celtic Christianity were very similar in their basic beliefs and both accepted the Pope's authority, they had differences in practice. The most debated issues were how to calculate the date of Easter and the style of head shaving for priests (called tonsure). Other differences were in how priests were ordained and how baptisms were done, and in the church services (liturgy). Experts have also noted that Irish and Scottish Christianity had relaxed rules about priests marrying, and church institutions were often very involved in everyday life. Also, dioceses (areas led by bishops) were not clearly set up. This meant that abbots (heads of monasteries) were often more important than bishops in the church hierarchy.

In the 600s, the Northumbrian church was increasingly influenced by the Roman style of Christianity. Important figures like St. Wilfred and Benedict Biscop strengthened ties with Rome. Wilfred was a key speaker for the Roman side at the Synod of Whitby in 664. King Oswiu of Northumbria called this meeting to decide which practices would be used in his kingdom. He chose the Roman way of shaving heads and calculating Easter. During this time, Northumbria was expanding into what is now Lowland Scotland. A bishopric (bishop's area) set up at Abercorn in West Lothian likely adopted Roman Christian practices after the Synod of Whitby. However, the Picts' victory at the Battle of Dunnichen in 685 ended Northumbrian control, and the bishop and his followers were forced out.

Nechtan mac Der-Ilei, king of the Picts from 706, seemed to want stronger links with the Northumbrian church. Before 714, he wrote to Ceolfrith, abbot of Wearmouth, asking for a clear explanation of the Roman position on Easter and help building a stone church "in the manner of the Romans." Some historians suggest there was a "Romanising group" among Nechtan's clergy. This is also suggested by a church at Rosemarkie in Ross and Cromarty, dedicated to St Peter (seen as the first Bishop of Rome), by the early 700s.

By the mid-700s, Iona and Ireland had accepted Roman practices. Iona's role as the main center of Scottish Christianity was disturbed by the arrival of the Vikings, who first raided and then conquered. Iona was attacked by Vikings in 795 and 802. In 806, 68 monks were killed, and the next year the abbot moved to Kells in Ireland, taking the relics of St. Columba with him. There were times when abbots and relics returned, but often more massacres followed. Orkney, Shetland, the Western Isles, and the Hebrides eventually fell to the pagan Norsemen, reducing the church's influence in the Highlands and Islands. The Viking threat may have forced the kingdoms of Dál Riata and the Picts to unite under Kenneth mac Alpin, traditionally in 843. In 849, Columba's relics were moved again, possibly to a church Kenneth mac Alpin built at Dunkeld. The abbot of this new monastery at Dunkeld became the Bishop of the new united kingdom, which would later be called the Kingdom of Scotland.

Early Monasteries

While there were many changes to monasteries in Europe and England, especially those linked to Cluny in France from the 900s, Scotland was mostly unaffected until the late 1000s. Physically, Scottish monasteries were very different from those in Europe. They were often isolated groups of wooden huts surrounded by a wall. Irish architectural influence can be seen in the surviving round towers at Brechin and Abernethy. Some early Scottish monasteries had families of abbots, who were often priests with families. This was famously seen at Dunkeld and Brechin, and also in other places north of the Forth, like Portmahomack and Mortlach.

Perhaps as a reaction to this, a group of reforming monks called Céli Dé (meaning "vassals of God"), also known as culdees, started in Ireland and spread to Scotland in the late 700s and early 800s. Some Céli Dé promised to live simply and without marriage. While some lived alone as hermits, others lived near or within existing monasteries. Even after new forms of monasticism were introduced from the 1000s, these Céli Dé were not replaced. Their tradition continued alongside the new monasteries until the 1200s.

Scottish monasteries played a big part in the Hiberno-Scottish mission, where Scottish and Irish clergy went on missions to the growing Frankish Empire (parts of modern France and Germany). They founded monasteries, often called Schottenklöster (meaning 'Gaelic monasteries' in German), most of which became Benedictine houses. Scottish monks, like St Cathróe of Metz, became local saints in these regions.

High Middle Ages

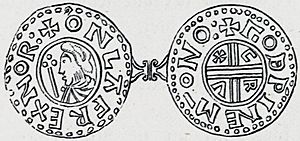

Christianity in Viking Scotland

Although the official conversion of Viking-controlled Scotland happened in the late 900s, there is evidence that Christianity had already started to spread in the Highland and Islands. Many islands are called Pabbay or Papa, which might mean "hermit's" or "priest's isle" from this time. Changes in burial customs and Viking place names using "-kirk" (meaning church) also suggest that Christianity was spreading before the official conversion.

According to the Orkneyinga Saga, written around 1230, the Northern Isles were Christianised by Olav Tryggvasson, king of Norway, in 995. He stopped at South Walls on his way from Ireland to Norway. The King called the local leader, Sigurd the Stout, and ordered him and his people to be baptised, threatening to kill them and burn their islands if they refused. This story might not be entirely true, but the islands did officially become Christian, getting their own bishop in the early 1000s. This bishopric was under the authority of Archbishops in York and Hamburg-Bremen at different times, and then under the Archbishop of Nidaros (modern Trondheim) until 1472.

Elsewhere in Viking Scotland, the story is less clear. There was a Bishop of Iona until the late 900s, then a gap of over a century, possibly filled by the Bishops of Orkney, before the first Bishop of Mann was appointed in 1079. A major effect of the Vikings converting was that they stopped raiding Christian sites. This may have allowed these sites to recover and become important centers for culture and learning again. It also likely reduced Viking violence and led to a more peaceful society in northern Scotland.

New Monasteries

New forms of monasticism from Europe came to Scotland with the help of the Saxon princess Queen Margaret (around 1045–93), the second wife of Máel Coluim III (ruled 1058–93), though her exact role is not fully clear. She was in contact with Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury, who sent some monks for a new Benedictine abbey at Dunfermline (around 1070).

Later monasteries founded by Margaret's sons, Edgar (ruled 1097–1107), Alexander (ruled 1107–24), and especially David I (ruled 1124–53), followed the "reformed" style that began with Cluny Abbey in France in the late 900s. Most belonged to new religious orders that started in France in the 1000s and 1100s. These orders emphasized the original Benedictine values, but also focused on prayer and serving the Mass. Reformed Benedictine, Augustinian, and Cistercian houses followed these ideas in different ways. This period also saw the introduction of more advanced church architecture, common in Europe and England, known as Romanesque. These buildings used rectangular stone blocks, allowing for massive, strong walls and round arches that could support heavy, rounded roofs.

The Augustinians, founded in northern Italy in the 1000s, set up their first priory in Scotland at Scone with Alexander I's support in 1115. By the early 1200s, Augustinians had joined, taken over, or reformed old Céli Dé sites like St Andrews and Holyrood Abbey, and created many new ones. The Cistercians, from Cîteaux in France, founded two important Scottish monasteries at Melrose (1136) and Dundrennan (1142). The Tironensians, from Tiron Abbey in France, founded monasteries at Selkirk, then Kelso, Arbroath, Lindores, and Kilwinning. The Cluniacs founded an abbey at Paisley. The Premonstratensians had foundations at Whithorn, and the Valliscaulians at Pluscarden. Military orders also came to Scotland under David I, with the Knights Templer founding Balantrodoch and the Knights Hospitallers being given Torphichen.

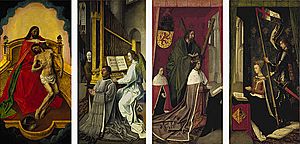

Popular Saints

Like all Christian countries, one of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the worship of saints. Irish saints who were especially honored included various figures called St Faelan and St. Colman, as well as saints Findbar and Finan. Columba remained a very important figure into the 1300s. William I (ruled 1165–1214) supported a new monastery at Arbroath Abbey for his relics, which were kept in the Monymusk Reliquary.

Local saints were important for local identities. In Strathclyde, the most important saint was St Kentigern, whose worship (under the nickname St. Mungo) focused on Glasgow. In Lothian, it was St Cuthbert, whose relics were carried across Northumbria after Lindisfarne was attacked by Vikings, before being placed in Durham Cathedral. After his death around 1115, a saint's cult grew in Orkney, Shetland, and northern Scotland around Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney.

One of the most important saint cults in Scotland was that of St Andrew, established on the east coast at Kilrymont by the Pictish kings as early as the 700s. The shrine, which from the 1100s was said to contain the saint's relics brought to Scotland by Saint Regulus, began to attract pilgrims from all over Scotland, England, and further away. By the 1100s, the site at Kilrymont was simply known as St. Andrews. It became more and more linked with Scottish national identity and the royal family. Its bishop would become the most important in the kingdom, even being called Bishop of Alba. The site became a renewed focus for devotion with the support of Queen Margaret, who also became important after she was made a saint in 1250. Her remains were moved to Dunfermline Abbey, making her one of the most revered national saints. In the late Middle Ages, "international" cults, especially those focused on the Virgin Mary and Christ, but also St Joseph, St. Anne, the Three Kings, and the Apostles, became more significant in Scotland.

Church Organization

Before the 1100s, unlike England, Scotland had few local parish churches. Churches had groups of clergy who served a wide area, often united by their devotion to a specific missionary saint. From this period, local landowners, perhaps following the example of David I, began to build churches on their land for the local population and provide them with land and a priest. This practice started in the south, spread to the north-east, and then to the west, becoming almost universal by the first survey of the Scottish Church for papal taxes in 1274. The management of these parishes was often given to local monasteries, a process called appropriation. By the time of the Reformation in the mid-1500s, 80 percent of Scottish parishes were managed this way.

Before the Norman period, Scotland did not have a clear system of dioceses (areas managed by bishops). There were bishoprics based on old churches, but some are barely mentioned in records, and there seem to have been long periods without a bishop. From around 1070, during Malcolm III's reign, there was a "Bishop of Alba" living at St. Andrews, but it's not clear how much authority he had over other bishops.

After the Norman Conquest of England, the Archbishops of both Canterbury and York claimed authority over the Scottish church. When David I arranged for John, a monk, to become Bishop of Glasgow around 1113, Thurstan, Archbishop of York, demanded the new bishop obey him. A long argument followed, with John traveling to Rome to appeal his case, but he was unsuccessful. John continued to refuse to obey, despite pressure from the Pope. A new bishopric of Carlisle was created in northern England, which was claimed as part of the Glasgow diocese and as territory by David I. In 1126, a new bishop was appointed to the southern Diocese of Galloway at Whithorn, who did obey York. This continued until the 1400s. David sent John to Rome to argue for the Bishop of St. Andrew's to become an independent archbishop. At one point, David and his bishops threatened to support an anti-pope (a rival Pope). When Bishop John died in 1147, David appointed another monk, Herbert, as his successor, and they continued to refuse to obey York.

The church in Scotland became independent after a special order from the Pope (Cum universi, 1192). This order made all Scottish bishoprics except Galloway formally independent of York and Canterbury. However, unlike Ireland, which received four Archbishops in the same century, Scotland did not get an Archbishop. Instead, the entire Scottish Church (Ecclesia Scoticana), with its individual Scottish bishoprics (except Whithorn/Galloway), became the "special daughter of the see of Rome." It was run by special councils made up of all the Scottish bishops, with the bishop of St Andrews becoming the most important figure.

Late Middle Ages

Church and Politics

Religion in the late Middle Ages had political aspects. Robert I carried the brecbennoch (or Monymusk reliquary), said to contain the remains of St. Columba, into battle at Bannockburn. During the Papal Schism (1378–1417), when there were rival Popes, the Scottish church and crown supported the Avignon Popes, along with France. Other countries, like England, supported the Roman Popes. In 1383, the Avignon Pope appointed Scotland's first cardinal, Walter Wardlaw, Bishop of Glasgow. When France stopped supporting the Avignon Pope, it caused problems for Scottish clergy studying in French universities. This led to the creation of Scotland's first university at St. Andrews from 1411–13. Scotland was one of the last churches to stop supporting the Avignon Pope and accept the compromise Pope, Martin V, suggested by the Council of Constance (1414–28). In later debates about whether church councils or the Pope had the final authority, loyalties often reflected political divisions in the country.

As in other parts of Europe, the weakening of papal authority during the Papal Schism allowed the Scottish Crown to gain control over important church appointments. This power was officially recognized by the Pope in 1487. This led to the king's friends and relatives being placed in key church positions. For example, King James IV's son, Alexander, was made Archbishop of St. Andrews at age 11. This increased the king's influence but also led to accusations that church appointments were based on money or family connections, not on merit. James IV used his pilgrimages to Tain and Whithorn to help bring those regions, which were on the edges of the kingdom, under royal control. Relations between the Scottish Crown and the Papacy were generally good, with James IV receiving special favors from the Pope. In 1472, St Andrews became the first archbishopric in the Scottish church, followed by Glasgow in 1492.

Everyday Religion

Traditional histories often said the late Medieval Scottish church was corrupt and unpopular. However, more recent research shows how it met the spiritual needs of different groups of people. Historians have noticed a decline in monastic life during this period. Many monasteries had fewer monks, and those who remained often lived more individual lives instead of communal ones. The number of new monasteries founded by nobles also decreased in the 1400s.

In contrast, towns saw a rise in mendicant orders of friars in the late 1400s. Unlike older monastic orders, friars focused on preaching and helping the general population. The Observant Friars were organized as a Scottish group from 1467, and the older Franciscans and the Dominicans were recognized as separate groups in the 1480s.

In most Scottish towns, unlike English towns where churches and parishes often multiplied, there was usually only one parish church. But as the idea of Purgatory (a place where souls are purified after death) became more important, the number of smaller chapels, priests, and Masses for the dead grew quickly. These were meant to help souls get to Heaven faster. The number of altars dedicated to saints, who could help in this process, also grew dramatically. St. Mary's in Dundee might have had 48 altars, and St Giles' in Edinburgh over 50. The number of saints celebrated in Scotland also increased, with about 90 added to the prayer book used in St Nicholas church in Aberdeen. New devotions related to Jesus and the Virgin Mary began to reach Scotland in the 1400s, including the Five Wounds of Christ, the Holy Blood, and the Holy Name of Jesus. There were also new religious feasts, such as celebrations of the Presentation, the Visitation, and Mary of the Snows.

In the early 1300s, the Pope managed to reduce the problem of priests holding two or more church positions at once (called pluralism). This problem often left parish churches without priests or with poorly trained ones. However, the number of low-paying church positions and a general shortage of clergy in Scotland, especially after the Black Death, meant this problem worsened in the 1400s. As a result, parish clergy often came from less educated backgrounds, leading to frequent complaints about their training. Although there's little clear evidence that standards were actually declining, this would become a major complaint during the Reformation.

New religious ideas, called Lollardry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early 1400s. Lollards were followers of John Wycliffe and later Jan Hus, who called for changes in the Church and disagreed with its teachings on the Eucharist (Communion). Despite some people being burned for these ideas and limited popular support for their anti-sacrament views, it probably remained a small movement. There were also efforts to make Scottish church services different from those in England. A printing press was set up in 1507 to print Scottish service books, replacing the English Sarum Use.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |