Battle of Bannockburn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Bannockburn |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First War of Scottish Independence | |||||||

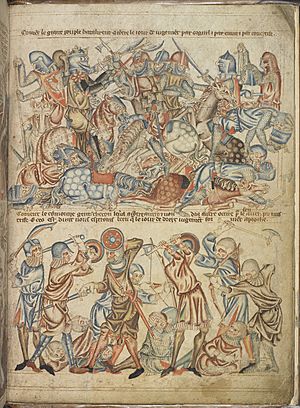

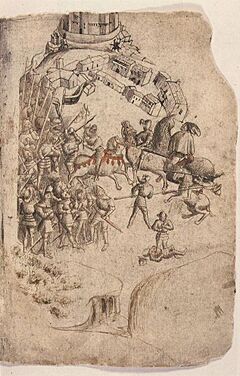

This depiction from the Scotichronicon (c. 1440) is the earliest-known image of the battle. King Robert wielding an axe and Edward II fleeing toward Stirling feature prominently, conflating incidents from the two days of battle. Corpus Christi College, Cambridge |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of Scotland | Kingdom of England | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sir Alexander Seton | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000–8,000 men | 20,000–25,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light (presumably around 100 casualties) |

|

||||||

| Designated | 21 March 2011 | ||||||

| Reference no. | BTL4 | ||||||

The Battle of Bannockburn was a huge fight in Scottish history. It happened on June 23–24, 1314. The battle was between the army of Robert the Bruce, who was the King of Scots, and the army of King Edward II of England.

This battle was a major part of the First War of Scottish Independence. Robert the Bruce and his Scottish army won a great victory. This win was a turning point in the war. It helped Scotland become an independent country again 14 years later. This was made official with the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton.

Contents

The Battle of Bannockburn

King Edward II of England invaded Scotland in 1313. He did this after Robert the Bruce demanded that everyone in Scotland support him as king. If they didn't, they would lose their lands. Stirling Castle, an important Scottish fortress held by the English, was under attack by the Scottish army.

King Edward gathered a massive army to help the castle. It was the largest army ever to invade Scotland. He had about 25,000 foot soldiers and 2,000 horsemen. Robert the Bruce had a much smaller army, around 6,000 soldiers. Edward's plan to save Stirling Castle failed when Bruce's army blocked his path.

The Scottish army was split into four groups. These groups used a special formation called schiltrons. A schiltron was a tight square of soldiers with long spears. King Robert led one group, his brother Edward Bruce led another. His nephew, Thomas Randolph, led a third. The fourth group was led by Sir James Douglas and Walter the Steward. Angus Og Macdonald, a friend of Bruce, brought many warriors from the Scottish Isles. They fought bravely alongside King Robert.

On the first day, Robert the Bruce famously killed an English knight, Sir Henry de Bohun, in single combat. The English then pulled back for the day. That night, a Scottish noble named Sir Alexander Seton, who was with the English army, secretly told King Robert that the English soldiers were feeling down. He said the Scots could win. Robert the Bruce decided to attack the English army fully the next day. He used his schiltrons in a new way, making them attack instead of just defend. This strategy helped the Scots win. Many English commanders were killed or captured.

The victory at Bannockburn is one of the most famous moments in Scottish history. People have remembered it in poems and art for centuries. Today, there's a visitor centre and a monument at a possible battle site. It helps people learn about this important event.

Why the Battle Happened

The Wars of Scottish Independence started in 1296. King Edward I of England wanted to control Scotland. He won some early battles. He also removed John Balliol from the Scottish throne. But the Scots fought back. They won at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297. Edward I then won at the Battle of Falkirk (1298). By 1304, England had taken over Scotland.

However, in 1306, Robert the Bruce became King of Scots. This restarted the war for Scottish freedom. When Edward I died in 1307, his son Edward II of England became king. Edward II was not as strong a leader as his father. This made things harder for the English in Scotland.

In 1313, Bruce told all remaining supporters of John Balliol to accept him as king. If they didn't, they would lose their lands. He also demanded that the English give up Stirling Castle. This castle was very important. It controlled the main route into the Scottish Highlands. Bruce's brother, Edward Bruce, began to attack the castle in 1314. The English agreed to surrender the castle if no one came to help it by mid-summer.

The English king, Edward II, had to respond to this challenge. He prepared a large army. He asked for 2,000 heavily armored cavalry and 13,000 foot soldiers. Not all of them arrived, but it was still the biggest army to ever invade Scotland. The Scottish army had about 7,000 men. Only about 500 of these were horsemen. The Scottish horsemen were mostly for scouting, not for charging. Scottish foot soldiers used axes, swords, and long spears. They had few archers. The English army was much larger, possibly one-and-a-half to three times bigger than the Scottish army.

Getting Ready for Battle

On the morning of June 23, 1314, it was still unclear if a battle would happen. The armies were about eight miles apart. King Robert the Bruce had time to decide his next move. He knew the English would keep marching towards Stirling Castle. Edward II rushed his troops, making them march 70 miles in one week. Many people think this was a bad decision. The English soldiers and horses became very tired and hungry.

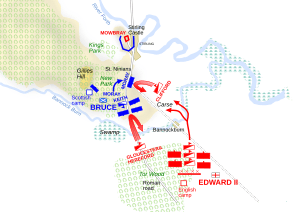

Edward II and his advisors planned for the battle. They knew the Scots might fight them in a marshy area near the River Forth. The English army moved in four groups. The Scots formed their defensive schiltrons. These were strong squares of men with long spears. Thomas Randolph led the Scottish front group. King Robert led the back group. His brother Edward led the third group. Sir James Douglas led the fourth group. The Scottish archers used longbows. They were good, but there were not many of them. They didn't play a big part in the battle. Some accounts say both sides also used slingers and crossbowmen.

The Battle Begins

Most battles in the Middle Ages were short, lasting only a few hours. The Battle of Bannockburn was unusual because it lasted two days. King Robert chose a flat field next to a forest called New Park for his camp. This forest helped protect his foot soldiers from the English cavalry. The Scots arranged their four groups in a diamond shape. Bruce was at the back, Douglas to the east, and Randolph to the north. Sir Robert Keith had 500 horsemen ready to help.

On June 23, 1314, two English cavalry groups moved forward. The first group was led by the Earl of Gloucester and the Earl of Hereford. A smaller group of about 300 soldiers, led by Sir Robert Clifford and Sir Henry de Beaumont, marched closer to the River Forth. Both groups were trying to reach Stirling Castle. The Hereford-Gloucester group crossed the Bannockburn stream first. They marched towards the woods where the Scots were hidden.

Bruce's Brave Act

King Robert was not fully ready for battle. He was on a small horse, wearing light armor, and carrying a battle axe. He was scouting the area. Henry de Bohun, the Earl of Hereford's nephew, saw the king. Bohun, fully armed with a lance, charged at Bruce. In a famous moment of single combat, Bruce waited until Bohun was close. As they passed, Bruce swung his axe and split Bohun's head.

The Scots then quickly attacked the English forces under Gloucester and Hereford. The English retreated back across the Bannockburn stream. This brave act by Robert the Bruce showed his leadership. It helped his soldiers respect him even more.

The second English cavalry group was led by Robert Clifford and Henry de Beaumont. Sir Thomas de Grey, whose son later wrote about the battle, was with them. Sir Henry de Beaumont told his men to wait for the Scots. Sir Thomas Grey warned him that the Scots would come too fast. Grey then bravely charged into the Scottish lines. His horse was killed, and he was captured. The Scots completely defeated this English group. Some English soldiers fled to Stirling Castle, while others went to the main English army. The main English army had moved to a plain near the River Forth. This area was a bad, wet marsh. The English spent the night there, feeling very discouraged.

The Main Fight

During the night, the English army crossed the Bannockburn stream. They set up their position on the plain beyond it. A Scottish knight, Alexander Seton, who was fighting for Edward II, left the English camp. He told Bruce that the English soldiers had low spirits. He encouraged Bruce to attack.

In the morning, the Scots marched out of New Park. At daybreak, Edward was surprised to see the Scottish pikemen coming out of the woods. They advanced towards his position. As Bruce's army got closer, they stopped and knelt to pray. Edward reportedly said, "They pray for mercy!" An attendant replied, "For mercy, yes, but from God, not you. These men will conquer or die."

The Earl of Gloucester had argued with the Earl of Hereford about who should lead the attack. He also tried to convince the king to delay the battle. The king accused him of being a coward. To prove him wrong, Gloucester charged forward to meet the Scots. Few soldiers went with him. When he reached the Scottish lines, he was quickly surrounded and killed.

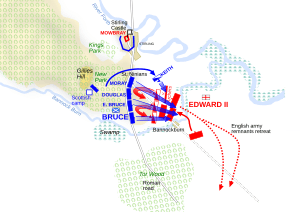

The Scottish schiltrons slowly pushed the English back. The English longbowmen tried to help their knights. But they were told to stop shooting to avoid hitting their own men. The English then tried to send their archers around the sides of the Scottish army. But 500 Scottish horsemen, led by Sir Robert Keith, quickly scattered them.

The English cavalry was trapped against the Bannockburn stream. They couldn't move easily. Their formations broke apart. It became clear to Aymer de Valence and Giles d'Argentan that the English had lost. They knew King Edward II had to be taken to safety. They grabbed the reins of the king's horse and pulled him away. About 500 knights of the royal bodyguard followed them.

English Retreat and Losses

Once they were safe from the battle, d'Argentan told the king, "Sire, I was meant to protect you. But since you are safe, I will say goodbye. I have never run from a battle, and I won't now." He turned his horse and charged back into the Scottish lines, where he was killed.

Edward fled with his bodyguards. Panic spread through the rest of the English army. Their defeat turned into a complete escape. King Edward first fled to Stirling Castle. But Sir Philip de Moubray, the castle commander, turned him away. The castle was about to be given to the Scots. Edward then fled to Dunbar Castle, chased by James Douglas and some horsemen. From Dunbar, he took a ship to Berwick.

The rest of the English army tried to escape to the English border, 90 miles south. Many were killed by the chasing Scottish army. Others were killed by people in the countryside they passed through. Only one large group of foot soldiers, Welsh spearmen, made it back to England. They were led by Sir Maurice de Berkeley. Most of them reached Carlisle. Historians believe that about 11,000 English foot soldiers were killed. Around 700 English knights were killed, and 500 more were captured for ransom. The Scottish army had very few losses, with only two knights killed.

What Happened After

Right after the battle, Stirling Castle, a very important Scottish fortress, surrendered to King Robert. He then destroyed parts of it. This was to stop the English from using it again. Bothwell Castle also surrendered. Many English nobles, including the Earl of Hereford, had hidden there. Other English strongholds like Dunbar and Jedburgh were also captured. By 1315, only Berwick was still under English control.

In exchange for the captured English nobles, Edward II released Robert's wife, Elizabeth de Burgh, his sisters Christina Bruce and Mary Bruce, and his daughter Marjorie Bruce. They had been held prisoner in England for eight years. After the battle, King Robert gave Sir Gilbert Hay of Erroll the important job of hereditary Lord High Constable of Scotland.

The English defeat opened up northern England to Scottish raids. It also allowed the Scottish invasion of Ireland. These events, along with the Declaration of Arbroath (a letter asking the Pope to recognize Scotland's independence), led to the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton in 1328. In this treaty, the English king finally recognized Scotland as an independent kingdom. He also accepted Robert the Bruce as its rightful king.

Notable Casualties

Many important people were killed or captured during the battle.

- Killed:

- Gilbert de Clare, 8th Earl of Gloucester

- Sir Giles d'Argentan

- John Lovel, 2nd Baron Lovel

- John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch

- Robert de Clifford, 1st Baron Clifford

- Sir Henry de Bohun

- William Marshal, Marshal of Ireland

- Edmund de Mauley, King's Steward

- Sir Robert de Felton of Litcham

- Malduin (Malcolm) MacGilchrist, 3rd Lord of Arrochar

- William de Vescy of Kildare

- John de Montfort, 2nd Baron Montfort

- Payn Tibetoft, 1st Baron Tibotot

- William de Hastelegh

- Edmund Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings

- Miles de Stapleton

- Simon Ward

- Michael de Poinyng

- Thomas de Ufford

- John de Elsingfelde

- Ralph de Beauchamp

- Captured:

- Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford

- John Segrave, 2nd Baron Segrave

- Maurice de Berkeley, 2nd Baron Berkeley

- Thomas de Berkeley

- Sir Marmaduke Tweng

- Ralph de Monthermer, 1st Baron Monthermer

- Robert de Umfraville, Earl of Angus

- Sir Anthony de Luci

- Sir Ingram de Umfraville

- Sir John Maltravers, 1st Baron Maltravers

- Sir Thomas de Grey of Heaton

- William le Latimer

- John Giffard

- Giles de Beauchamp

- Gilbert de Bohun

- Thomas de Ferrers

- Roger Corbet

- John Bluwet

- Bartholomew de Enefeld

- John Cysrewast

- John de Clavering

Remembering Bannockburn

The Visitor Centre

In 1932, a group called the Bannockburn Preservation Committee bought land for a monument. More land was bought later to make it easier for visitors to come. A modern monument was built in a field where the armies might have camped. It has two curved walls that show the two sides of the battle. Nearby is a statue of Robert the Bruce, made by Pilkington Jackson. The monument and the visitor centre are popular places for tourists. The battlefield is now a protected historic site in Scotland.

The National Trust for Scotland runs the Bannockburn Visitor Centre. It is open every day from March to October. The old building was replaced with a new one in 2014. This new centre was inspired by traditional Scottish buildings. It was a project between the National Trust for Scotland and Historic Environment Scotland. It was funded by the Scottish Government and the Heritage Lottery Fund. One of the cool things at the new centre is a computer game where you can play as a soldier in the battle.

Songs and Art

The Battle of Bannockburn is remembered in many creative ways. "Scots Wha Hae" is a famous patriotic poem by Robert Burns. The chorus of Scotland's unofficial national anthem, Flower of Scotland, also talks about Scotland's victory over the English at Bannockburn.

Many artists have painted scenes from the battle. John Duncan and Eric Harald Macbeth Robertson both painted Bruce fighting de Bohun. John Phillip painted Bruce praying before the battle. John Hassall and William Findlay also created paintings about the battle.

The German heavy metal band Grave Digger has a song called "The Battle Of Bannockburn" on their 1998 album Knights of the Cross. In 2016, the Swedish metal band Sabaton released a song called "Blood of Bannockburn" on their album The Last Stand.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Bannockburn para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Bannockburn para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |