Geography of Scotland in the Middle Ages facts for kids

The geography of Scotland in the Middle Ages is all about the land of Scotland between the early 400s (when the Romans left) and the early 1500s (when the Renaissance began). Scotland's shape was decided by its physical features. It has a long coastline with many inlets, islands, and inland lakes called lochs. Much of the land is high above sea level, and it rains a lot. Scotland is split into two main parts: the Highlands and Islands and the Lowlands. These areas were further divided by mountains, hills, and marshy bogs. This made travel and communication hard. It also made it tough for one ruler to control the whole country, and for invading armies to move around.

Early settlement patterns in Scotland were not much changed by the Romans. People continued to live in Iron Age hill forts and promontory forts in the south. In the north, they lived in Brochs and wheel houses. Studies of place names and old sites show that the Picts settled mostly around the north-east coast. The early Gaelic people lived mainly in the western mainland and nearby islands. The Anglian people settled in the south-east, reaching into West Lothian. Later, Norse settlers were most common in Orkney and Shetland. There were fewer Norse settlements in the Western Islands.

From the time of King David I (who ruled from 1124 to 1153), we see the first towns in Scotland, called burghs. Many of these started on the east coast. They grew in size and importance throughout the Middle Ages. By the late 1200s, over 50 royal burghs had been set up. Many more burghs were created between 1450 and 1516. These towns were important places for government, local trade, and international trade. In the early Middle Ages, people in Scotland spoke different languages. These included Gaelic, Pictish, Cumbric, and English. Over time, Gaelic, English, and Norse replaced Cumbric and Pictish. From King David I's reign, French became the language of the royal court and nobles. By the late Middle Ages, Scots (which came mostly from Old English) became the main language.

During this period, Scotland's borders slowly grew. The kings of Alba started with a small area in the east. Through battles, agreements, and treaties, they expanded their control. Eventually, Scotland reached almost its modern-day borders. For most of the Middle Ages, the king and his court moved around a lot. Scone and Dunfermline were important centers. Later, Roxburgh, Stirling, and Perth became key places. Edinburgh became the political capital in the 1300s. Iona was an important religious center, but it became less important after Viking raids around 800 AD. Even though kings tried to create a new religious center at Dunkeld, St. Andrews on the east coast became the most important religious place in the kingdom.

Contents

Scotland's Landscape: Mountains, Lakes, and Coastlines

Modern Scotland is about half the size of England and Wales. But because of its many inlets, islands, and inland lochs (lakes), it has a very long coastline, about 4,000 miles! Only a small part of Scotland (about one-fifth) is less than 60 meters above sea level. Scotland is located on the east side of the Atlantic Ocean. This means it gets a lot of rain. Today, some parts get over 1,000 cm of rain each year. This heavy rain helped create large areas of peat bog (wet, spongy ground). The bogs are acidic, and with strong winds and salty sea spray, most of the islands became treeless.

Hills, mountains, and marshes made it very hard to travel and conquer land within Scotland. This might have led to different parts of the country having their own rulers. The early Middle Ages saw a colder and wetter climate. This made some land less useful for farming. But from about 1150 to 1300, the weather improved. Summers were warm and dry, and winters were milder. This allowed people to farm at higher elevations and made land more productive. In the late Middle Ages, temperatures dropped again. Colder, wetter conditions limited farming, especially in the Highlands.

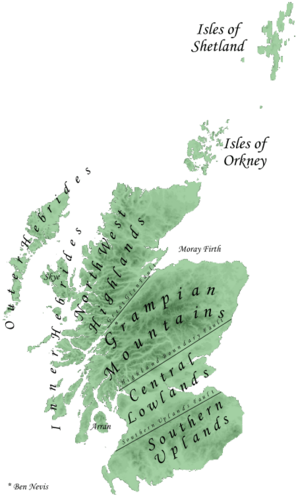

The main feature of Scotland's geography is the difference between the Highlands and Islands in the north and west, and the Lowlands in the south and east. The Highlands are split into the Northwest Highlands and the Grampian Mountains by a large fault line called the Great Glen. The Lowlands are divided into the fertile Central Lowlands and the higher Southern Uplands. The Cheviot hills, part of the Southern Uplands, became the border with England by the end of this period.

Some of these regions were further divided by mountains, big rivers, and marshes. The Central Lowland belt is about 50 miles wide. It has most of the good farming land and is easier to travel through. Because of this, it could support more towns and a more traditional medieval government. The Southern Uplands and the Highlands were less productive for farming and much harder to govern. This geography helped protect Scotland. Small English attacks had to cross the difficult Southern Uplands. Even two major English attempts to conquer Scotland failed to get into the Highlands. This meant that Scottish resistance could start from the Highlands and try to take back the Lowlands. However, it also made these areas difficult for Scottish kings to control. Much of Scotland's political history after the Wars of Scottish Independence was about trying to solve these problems of local control.

Where People Lived and How Many There Were

Roman influence in southern Scotland did not change how people settled. Iron Age hill forts and promontory forts continued to be used in the early Middle Ages. These forts often had stone or timber walls, sometimes with a palisade (a fence of strong wooden stakes). The large number of these forts suggests that kings and nobles moved around their lands. They did this to control and manage their areas. In the Northern and Western Isles, old Brochs and wheel houses were still used. But over time, people started building simpler, smaller houses. In the south, there were a few large timber halls, similar to those found in Anglo-Saxon England from the 600s. In areas settled by Scandinavians, there wasn't much timber. So, people used local materials like stone and turf to build houses.

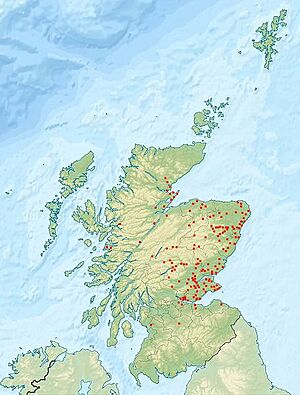

Place names suggest that the Picts settled most densely in the north-east coastal plain. This includes modern Fife, Perthshire, Angus, Aberdeen, and around the Moray Firth. However, later Gaelic migration might have removed some Pictish names. Early Gaelic settlement seems to have been in the western mainland of Scotland. This was between Cowal and Ardnamurchan, and the nearby islands. Later, in the 700s, they spread up the West coast. There is evidence of Anglian settlement in south-east Scotland, reaching into West Lothian. It also extended a bit into south-western Scotland. Later Norse settlement was probably largest in Orkney and Shetland. There was lighter settlement in the Western Islands, especially the Hebrides. On the mainland, Norse settlers were in Caithness, stretching along fertile river valleys through Sutherland and into Ross. There was also a lot of settlement in Bernicia, which reached into the modern borders and Lowlands.

From the time of King David I, we have records of burghs. These were towns that were given special legal rights by the king. Most of the burghs that received charters (official documents) during David's reign were probably already existing settlements. The charters were copied almost exactly from those used in England. Early citizens of these burghs, called burgesses, were usually English or Flemish (from Flanders). They could charge tolls and fines on traders in the area outside their towns. Most of the early burghs were on the east coast. These included the largest and wealthiest ones, like Aberdeen, Berwick, Perth, and Edinburgh. Their growth was helped by trade with mainland Europe. In the south-west, Glasgow, Ayr, and Kirkcudbright benefited from sea trade with Ireland, and to a lesser extent, France and Spain.

Burghs were usually surrounded by a palisade or had a castle. They typically had a market place, often a wide main street or a crossroads. This was usually marked by a mercat cross. Houses for the burgesses and other people were built nearby. About 15 burghs can be traced back to King David I's reign. By 1296, there is evidence of 55 burghs. Besides the main royal burghs, many smaller burghs were created in the late Middle Ages. These were called baronial and ecclesiastical burghs. 51 of them were created between 1450 and 1516. Most were much smaller than the royal burghs. They were not involved in international trade. They mainly served as local markets and centers for craftspeople.

It is hard to know exactly how many people lived in early medieval Scotland. There are almost no written records. Some guesses suggest about 10,000 people in Dál Riata and 80,000 to 100,000 in Pictland, which was probably the largest region. It is likely that the 400s and 500s saw more deaths because of the bubonic plague. This might have reduced the population. Studies of burial sites from this time show that people lived only about 26 to 29 years on average. This suggests a society where many children were born, but many also died young. This is similar to many developing countries today. It meant there were not many workers compared to the number of people to feed. This made it hard to produce extra food, which would allow the population to grow and societies to become more complex.

From the creation of the kingdom of Alba in the 900s, until the Black Death arrived in 1349, the population might have grown from half a million to a million. This is based on how much farmable land there was. We don't have exact records of the plague's impact. But there are many stories about abandoned land in the years after. If Scotland was like England, the population might have dropped to as low as half a million by the end of the 1400s. Compared to later times, like after the highland clearances and the Industrial Revolution, these numbers would have been spread fairly evenly across the kingdom. About half the people lived north of the River Tay. Perhaps ten percent of the population lived in one of the burghs. It is thought that burghs had an average population of about 2,000. But many would have been much smaller than 1,000. The largest, Edinburgh, probably had over 10,000 people by the end of this period.

Languages Spoken in Medieval Scotland

Today, experts divide Celtic languages into two main groups. One is P-Celtic, which includes Welsh, Breton, Cornish, and Cumbric. The other is Q-Celtic, which includes Irish, Manx, and Gaelic. The Pictish language is a bit of a mystery. The Picts did not write their own language. All that is left are place names and a few carvings in Irish ogham script. Most modern experts agree that Pictish belonged to the P-Celtic group, even though we don't know much about it.

Old records and place names show how Pictish in the north and Cumbric in the south were gradually replaced. They were replaced by Gaelic, Old English, and later Norse during this time. By the High Middle Ages, most people in Scotland spoke Gaelic. They simply called it Scottish, or in Latin, lingua Scotica.

In the Northern Isles, the Norse language brought by Scandinavian settlers became the local Norn. This language lasted until the late 1700s. Norse might also have been spoken in the Outer Hebrides until the 1500s. French, Flemish, and especially English became the main languages in Scottish burghs. Most of these towns were in the south and east. This was an area where Anglian settlers had already brought a form of Old English. In the late 1100s, a writer named Adam of Dryburgh described Lowland Lothian as "the Land of the English in the Kingdom of the Scots." From at least the time King David I became king, Gaelic stopped being the main language of the royal court. It was replaced by Norman French. This change then spread to government offices, noble castles, and the higher ranks of the Church.

In the late Middle Ages, Middle Scots became the main language of the country. People often called it English, but this was not quite right. It came mostly from Old English, but also had parts from Gaelic and French. Even though it was similar to the language spoken in northern England, it became a separate language from the late 1300s. The ruling class started using Scots as they slowly stopped using French. By the 1400s, Scots was the language of government. Acts of parliament, council records, and treasury accounts almost all used Scots from the reign of King James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, which was once common north of the River Tay, began to slowly decline.

How Scotland's Political Map Changed

At its start in the 900s, the combined Gaelic and Pictish kingdom of Alba was only a small part of what is now Scotland. Even when more lands were added in the 900s and 1000s, the name "Scotia" only referred to the area between the Forth River, the central Grampian Mountains, and the River Spey. It only began to describe all the lands under the Scottish crown from the mid-1100s. Scotland grew into a larger kingdom slowly. This happened through conquering new lands, stopping rebellions, and placing loyal officials (agents of the crown) in charge. Neighboring independent kings became subject to Alba and eventually disappeared from records.

In the 800s, the term mormaer (meaning "great steward") started appearing in records. This described the rulers of Moray, Strathearn, Buchan, Angus, and Mearns. They might have acted as "marcher lords" (lords guarding the borders) for the kingdom to fight against Viking threats. Later, the country became more unified because of feudalism introduced by King David I. Especially in the east and south, where the king's power was strongest, new lordships were set up, often based around castles. Administrative sheriffdoms were also created, which overlapped with the existing local thegns (nobles).

Most regions that became Scotland had strong cultural and economic links to other places. These included England, Ireland, Scandinavia, and mainland Europe. Travel within Scotland was hard, and the country did not have one obvious central place. The king kept a court that moved around, without a fixed "capital." Dunfermline became a major royal center during the reign of King Malcolm III. King David I tried to develop Roxburgh as a royal center. But in the 1100s and 1200s, more official documents were issued at Scone than anywhere else. Other popular places in the early part of this era were nearby Perth, Stirling, Dunfermline, and Edinburgh.

In the later Middle Ages, the king moved between royal castles, especially Perth and Stirling. He also held court sessions throughout the kingdom. Edinburgh only started to become the capital during the reign of King James III. This made the king quite unpopular. Iona was an early religious center. It was said to be the burial place of the kings of Alba until the late 1000s. But it declined because of Viking raids starting in 794. Some holy items of St. Columba were moved from Iona to Dunkeld in the mid-800s. Dunkeld was closer to the center of the kingdom and near Scone, where coronations happened. This might have been an attempt to create a new religious center. However, St. Andrews became the center of the Scottish church. It had a famous religious story and was probably set up on the east coast by Pictish kings as early as the 700s. St. Andrews was never a major political capital or trading center.

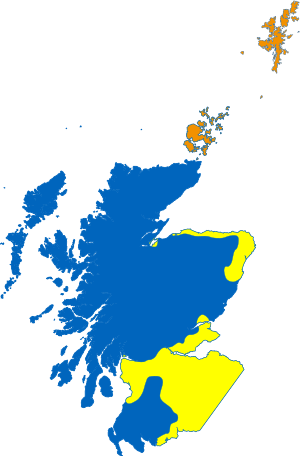

Until the 1200s, the borders with England changed a lot. Northumbria and Cumbria were added to Scotland by King David I. But they were lost under his grandson, King Malcolm IV, in 1157. The Treaty of York (1237) and the Treaty of Perth (1266) set the borders of Scotland with England and Norway. These borders were very close to today's boundaries. The Isle of Man came under English control in the 1300s, even though Scotland tried several times to get it back. The English were able to take a large part of the Lowlands under King Edward III. But Scotland slowly regained these lands, especially when England was busy with the Wars of the Roses (1455–1485).

In 1468, Scotland gained its last big piece of land. This happened when King James III married Margaret of Denmark. He received the Orkney Islands and the Shetland Islands as part of her dowry (payment for the marriage). In 1482, Berwick, a border fortress and the largest port in Medieval Scotland, fell to the English again. This was the final time it changed hands. The only uncertain area was a small region called the Debatable Lands at the south-west end of the border. This area was finally divided by a French-led commission in 1552.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |