History of Cumbria facts for kids

The history of Cumbria as a county in England began in 1974. But the land and its people have a very long story, going back thousands of years! Cumbria is a beautiful area with mountains, lakes, and a coastline. It has seen many invasions, migrations, and settlements. There were also lots of battles between the English and the Scots.

Contents

- What is Cumbria?

- Ancient Cumbria: Before the Romans

- Roman Cumbria: Conquest and Control

- Medieval Cumbria: From Chaos to Kingdoms

- Early Medieval Cumbria: After the Romans (410–1066)

- Warring Tribes and the Kingdom of Rheged

- Christian Saints

- Life in Early Medieval Cumbria

- The Angles: Northumbrian Rule (c. 600–875)

- Church and State

- Vikings, Strathclyde British, Scots, English (875–1066)

- Strathclyde British Settlement

- Scandinavian Settlement

- The Scots and 'Cumbria'

- The English and Cumbria

- High Medieval Cumbria: Norman Rule and Border Conflicts (1066–1272)

- Later Medieval Cumbria: Wars and Fortifications (1272–1485)

- Early Medieval Cumbria: After the Romans (410–1066)

- Early Modern Cumbria: Tudors and Stuarts (1485–1714)

- Georgian and Victorian Periods: Industry and the Lake District (1714–1901)

- 20th Century: Modern Cumbria is Formed

- 21st Century: Recent Events

- Timeline

- See also

- Images for kids

What is Cumbria?

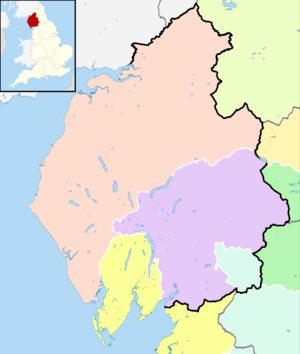

Cumbria became a county in 1974. It was formed from parts of older counties like Cumberland, Westmorland, and parts of Lancashire and Yorkshire. The area has a rich human history that goes back to ancient times. It's a county of big differences. You can find tall mountains and lakes in the middle. There are also flat, fertile plains in the north. Gentle rolling hills are in the south.

Today, Cumbria relies on farming and tourism for its economy. But in the past, industries like mining were very important. For a long time, Cumbria was a disputed area between England and Scotland. Scottish raids were common until 1707. Before that, the long coastline was often attacked by Irish and Norse raiders.

Cumbria used to be quite isolated. Before railways, it was hard to reach many parts of the region. Even now, some roads can be tricky. In bad winters, some valleys can be cut off. Some groups of ancient Britons lived here until about the 10th century. This was long after most of England had become "English." The Norse people also kept their own identity for a long time. Cumbria was often seen as a "no man's land" between England and Scotland. This meant Cumbrians had their own unique identity.

This article tells the story of the land and people that became Cumbria in 1974. It is still a ceremonial county today. The name Cumbria was used in the 10th century AD. Back then, it described a part of the small Kingdom of Strathclyde. Later, in the 12th century, Cumberland and Westmorland became official administrative counties.

Ancient Cumbria: Before the Romans

The story of Cumbria before the Romans is called 'Prehistoric Cumbria'. Archaeologists have found many ancient tools, objects, and pots. They have also found monuments like stone circles. These discoveries help us understand early life here.

The first people to live permanently in Cumbria lived in caves. This was during the Mesolithic era. Later, in the Neolithic period, people built large monuments. They also ran an "axe factory" where stone axes were made. These axes were traded all over the country. The Bronze Age continued many of these ways of life. By the Iron Age, Celtic tribes lived in Cumbria. These might have been the Carvetii and Setantii tribes.

First Humans: Late Upper Palaeolithic Era

The earliest signs of humans in Cumbria are from Kirkhead Cave. This was around 11,400–10,800 BC. Finds here are very important for understanding early settlement in Britain. Other stone tools were found in nearby caves. These included bones from reindeer and elk.

During a very cold period that followed, these early sites were left empty. Cumbria was not permanently lived in again until the Mesolithic era.

Mesolithic Era: Warming Climate and Coastal Life

The Mesolithic era in Cumbria brought a warmer climate. People likely traveled across Morecambe Bay and settled along the fertile coast. The central mountain region was heavily forested. So, humans probably stayed near the coast and river mouths. These areas offered plenty of food, fresh water, and shelter.

Early Mesolithic evidence comes mostly from caves. In 2013, human bones found in Kents Bank Cavern were dated to this time. This was the most northern early Mesolithic human remains found in the British Isles. Later Mesolithic evidence includes pits and signs of burning heathland. This suggests people managed the landscape.

Large sites where flint tools were made have been found. These are at Eskmeals and Walney. People worked flints washed up from the Irish Sea into tools. At Eskmeals, over 34,000 worked flint pieces were found. Wooden raft-like structures suggest people lived there for long periods. These sites were used for thousands of years.

Neolithic Era: Monuments and Axe Factories

The Neolithic era left much more visible evidence. This includes stone axes and monuments like stone circles. However, few settlement traces or pottery finds have been discovered. This was a time of new technologies and more people. The change from Mesolithic to Neolithic was slow. It is marked by new tools, pottery, and ceremonial sites.

People from coastal communities likely moved inland. They followed rivers into the heart of the Lake District. We don't know how many moved. Some believe coastal living continued, but activity also spread inland.

A well-known Neolithic site is Ehenside Tarn. It had unfinished and polished axes, pottery, and animal bones. This shows people still hunted alongside farming. Ehenside Tarn also highlights the use of wetlands. Finds were discovered when the tarn was drained. A standing stone near the tarn suggests it was a special place.

Most axe finds are in South Cumbria, especially Furness and Walney. This is because of the famous Langdale axe industry. Thousands of axe heads were made there from green volcanic rock. These axes were used for weapons and ceremonies. They have been found all over the United Kingdom.

During this time, stone circles and henges were built. Cumbria has many preserved monuments. Examples include Mayburgh Henge and King Arthur's Round Table, Cumbria near Penrith. The Castlerigg Stone Circle near Keswick is also impressive. Long Meg and Her Daughters might also be from this time.

Some stones have designs like spirals and circles. These might have shown other monuments or gathering places. They could also have marked routes through the landscape. Stone circles likely had uses beyond trade and ritual. For example, the Long Meg stone aligns with the midwinter sunset. Different colored stones might relate to observations of the sun.

Bronze Age: Permanent Settlements and Burials

By the Bronze Age, settlements in Cumbria became more permanent. The change from Neolithic to Bronze Age was gradual. Unlike southern England, beaker pottery burials are rare here. Instead, circular wooden and stone structures were used for burials.

Early Bronze Age evidence shows more woodland clearing and cereal farming. This is seen in pollen records. Few occupation sites exist, but aerial photos show some. Plasketlands, for example, shows a mix of farming and natural resources.

Collared urns have been found at various sites. Activity around Morecambe Bay was less than on the west coast. But there is evidence of settlement on Walney Island.

South Cumbria has many perforated axe-hammers. These were likely placed intentionally. Their increased use probably led to the decline of the Langdale axe factory around 1500 BCE. Copper and bronze tools arrived slowly in Cumbria. By 1200 BCE, trade and technology seemed to break down between northern and southern England.

For burials, both uncremated bodies (inhumations) and cremations happened. Cremations were more common. Most burials were with cairns, but other monuments were also used. Often, there were multiple burials without monuments. Cremated bones were placed in food vessels or urns. Ritual items were sometimes placed in graves.

Bronze Age artifacts have been found across Cumbria. These include axe heads, a sword, a rapier, and a carved granite ball. A gold necklace from France or Ireland was found at Greysouthen. A wooden fence was found near Carlisle. There's a link between axe-hammers and bronze objects in Furness. Most of the 200 bronze tools found in Cumbria are from Furness and Cartmel. Early Bronze Age metalwork is found along valleys and plains. Connections with Ireland are seen on the west coast. Later, objects were placed in wet areas, possibly for rituals. Hoards of bronze metalwork are rare in Cumbria.

Evidence of metalworking is scarce. Some copper mining signs are near Coniston. A clay pipe for a furnace was found at Ewanrigg. Stone molds were found at Croglin.

Ritual sites are visible across the county. Cairns and round barrows are common. Stone circles like Birkrigg stone circle, Long Meg and Her Daughters, and Swinside are impressive. The Furness district has many bronze artifacts. This suggests it was a special place. In the Late Bronze Age, fortified hilltop settlements appeared. These might have been early hill-forts. Many were abandoned due to climate change.

Iron Age: Celtic Tribes and Hillforts

The British Iron Age brought Celtic culture, art, and languages. Iron production increased. People in Britain were divided into tribes. In Cumbria, the Carvetii might have been dominant. Their center could have been Carlisle or Clifton Dykes. The Setantii might have been in the south. Both may have joined the Brigantes, a larger tribe in northern England. Historians debate the exact location and status of these tribes. They probably spoke Cumbric, an ancient British language. This language likely named many Cumbrian rivers and mountains.

Many Iron Age settlement remains exist. These include hill forts like Maiden Castle and Dunmallard Hill. Hundreds of smaller settlements and field systems are also found. However, firm dates for Iron Age activity are rare. In North Cumbria, hillforts date to around 500 BCE. A burial and a bog body have also been found.

Aerial photos show many enclosed sites in the Solway Plain. Some Roman sites might have been re-used Iron Age locations. Early Iron Age finds in West Cumbria are limited. In the south, hillforts have been identified. However, Cumbria seems to lack "developed hillforts." This suggests many were abandoned before the Romans arrived.

Climate change likely caused the abandonment of land and settlements. Between 1250 BCE and 800 BCE, the climate worsened. Upland farming became difficult. This might have led to a "population crisis."

However, the climate improved from 800 BCE to 100 CE. More forests were cleared for cereal farming. This is seen in pollen records. A slight rise in sea level might explain the lack of low-lying settlements. Evidence for the Late Iron Age is sparse. But aerial photos show many enclosures in upland areas. This suggests the Brigantes' territory was well-populated. Historians now believe hillforts were economic centers, not just power bases. The northwest, including Cumbria, might have been "progressive and entrepreneurial."

The traditional Iron Age roundhouse was used by the Carvetii. Sometimes, dry-stone walls were used instead of banks. A roundhouse at Wolsty Hall shows a unique northern style. Later, in the Roman period, round structures were replaced by rectangular buildings.

Most people lived in small, scattered family groups. They practiced mixed agriculture, with fields for crops and pastures for animals.

Evidence of burial practices is very rare. Inhumations have been found. Two rare cemeteries with multiple bodies exist. One burial included a "warrior" with weapons and a horse. Bog bodies found in Cumbria are hard to date. They were buried with wooden sticks, similar to other bog burials.

Iron Age metalwork hoards in Cumbria show a regional style. They are mostly small numbers of weapons buried away from settlements. This fits the picture of small, scattered farms. A beautiful iron sword with a bronze scabbard was found near Cockermouth. It is now in the British Museum.

Roman Cumbria: Conquest and Control

Roman Cumbria was in the far northwest of Roman Britain. The Romans decided to conquer the area after a rebellion by Venutius. This rebellion threatened to turn the Brigantes and their allies against Rome. After conquering and settling the area, the Romans built the Stanegate road and coastal defenses. Later, Emperor Hadrian decided to build a strong stone wall. This was Hadrian's Wall. Although it was briefly abandoned for a wall further north, Hadrian's Wall became the main frontier for the rest of Roman rule.

Any unrest during the Roman occupation was likely from tribes north of the Wall. Or it was from power struggles in Rome. There is no sign that the Brigantes caused trouble. So, the local people probably became Romanized to different degrees, especially near the forts.

Conquest and Early Control: 71–117 AD

After the Romans first conquered Britain in 43 AD, the Brigantes remained independent. Their queen, Cartimandua, was loyal to Rome. Her husband, Venutius, might have been a Carvetian. He may have brought Cumbria into the Brigantian group. Cartimandua might have ruled east of the Pennines, and Venutius west in Cumbria.

Cartimandua and Venutius were loyal to Rome and received protection. But they divorced, and Venutius rebelled twice. The first rebellion failed. The second, in 69 AD, happened during a time of Roman instability. The Romans evacuated Cartimandua, leaving Venutius in charge.

The Romans couldn't accept a large, formerly friendly tribe being anti-Roman. So, they began conquering the Brigantes two years later. Tacitus praised Gnaeus Julius Agricola, his father-in-law, for conquering the north. But much was done by earlier governors. Carbon dating shows the Roman fort at Carlisle was built around 72 AD. Agricola led a legion in the west, while others fought in the east. Roman ships also sailed up rivers to surprise the enemy.

Eventually, Roman forces moved from Corbridge to Carlisle. They established a fort there in 72/73 AD. Carlisle became an important center.

From 87 AD to 117 AD, the northern frontier was strengthened. Roman forces slowly withdrew to the Solway-Tyne line. This was an orderly retreat, not a defeat.

Besides the Stanegate line, other forts were built along the Solway Coast. These included Maryport and Moresby. A road from Carlisle to Maryport had forts at Old Carlisle and Papcastle. Forts in the east, like Old Penrith and Brougham, might have been enlarged. A fort at Troutbeck, Eden might have been built later. Roads connected these forts. For example, a road from Ambleside to Hardknott Roman Fort was built. From Kirkby Thore, the Maiden Way road ran north. In the south, forts might have existed near Ravenglass and Kendal.

Hadrian, Antoninus, and Severus: 117–211 AD

Between 117 and 119 AD, there might have been a war with Britons in the west. The Romans responded by building a turf and timber frontier. This was the "Turf Wall".

But Emperor Hadrian (117–138 AD) wanted something stronger. Perhaps the military situation was serious, or he wanted to define the empire's borders. Hadrian, an amateur architect, came to Britain in 122 AD. He oversaw the building of Hadrian's Wall. It was mostly finished in less than ten years. The Wall stretched from Bowness-on-Solway to Wallsend. It also had military posts down the Cumbrian coast.

Cumbria had several forts and milecastles along the Wall. Petriana (Stanwix) was the largest, housing cavalry. It was likely the Wall's headquarters. Little of Petriana remains today. The largest visible remains in Cumbria are at Birdoswald. A ditch was north of the Wall, and an earthwork (the Vallum) was south. Initially, Stanegate forts were used, but then forts were built directly on the Wall. Roman forts in Cumbria housed auxiliary units, not legions. Outpost forts like Bewcastle Roman Fort were built north of the Wall.

Just twenty years after Hadrian's Wall began, Emperor Antoninus Pius (138–161 AD) almost abandoned it. He focused on his own wall in central Scotland, the Antonine Wall. The coastal forts were also left. But Antoninus failed to control southern Scotland. So, the Romans returned to Hadrian's Wall in 164 AD. Garrisons remained there until the early 5th century.

The Wall divided the Carvetii's land. This might have caused local raids. The early 160s saw troubles on the northern frontier. Building continued into the 3rd century, showing more unrest. Around 180 AD, hostile forces crossed the Wall. But the main pressure came from tribes further north. Emperor Septimius Severus came to Britain in 209 AD. He strengthened Hadrian's Wall. He may also have established the "civitas" (a form of local government) of the Carvetii at Carlisle.

Roman Life and Decline: 211–410 AD

After Severus's settlement, the north had a period of peace. Forts were kept in good repair. Power might have been shared between local government and the military. Some forts, like Hardknott, might have been demilitarized. Smaller barracks suggest fewer soldiers. Changes in the army led to more relaxed discipline.

Despite peace in Cumbria, the empire faced internal problems. Inflation and power struggles affected Britain. Rebellions in Gaul and by usurpers like Carausius affected troops in Cumbria. There is evidence of fire damage at Ravenglass. Emperor Constantius I came to Britain twice to put down trouble. Rebuilding took place. In the early 4th century, the strategy changed. The Wall became less of a barrier. Forts became strongpoints.

Reforms by Emperors Diocletian and Constantine the Great brought prosperity to southern Britain. But this peace didn't last after Constantine's death in 337. Civil wars returned, affecting Britain. Emperor Constans visited Britain in 342–343, possibly due to problems on the northern frontier. The west coast might have been strengthened. Forts like Ravenglass and Maryport were maintained. Some Hadrianic coastal forts were reoccupied.

The defeat of Magnentius in 353 increased troubles. Attacks on the province happened in 360. Secret agents called the Areani were involved in a plot in 367–368. They were accused of helping enemies like the Picts and Saxons for bribes.

Some outpost forts were not maintained after 367. But Count Theodosius or local leaders did much rebuilding. Birdoswald fort showed changes, becoming more like a local leader's fortress. Local people might have started defending themselves as Roman authority weakened. The Roman "abandonment" of Britain was not sudden. Local Roman commanders became local leaders. The Roman troops became local militias. This was a "return to tribalism."

Daily Life in Roman Cumbria

It's hard to know exactly what life was like in Roman Cumbria. The Vindolanda tablets give us some clues about life on the frontier. Auxiliary troops in the forts had a big impact. Land around forts was used for parades, farming, and mining. Civilian settlements called vicus grew around most forts. These had merchants, traders, and artisans. They were drawn by business opportunities from supplying the troops. Some town life began, but it wasn't as developed as in southern England.

Apart from fort settlements, Roman Cumbria had scattered rural communities. These were in fertile areas like the Solway Plain and river valleys. Most people lived in single family groups. They practiced mixed agriculture. Later, there was a shift from crops to pasture. This might have been due to less demand from the Roman military or lower productivity.

The long-term effects of Roman rule on native Cumbrians are hard to judge. Artifacts like the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan show a mix of Roman and Celtic art. This suggests that Roman culture was sometimes just a "surface layer." The pan was likely a souvenir of Hadrian's Wall. It shows the Wall was famous even then.

Religion helped bridge Roman and Celtic ways. After the Druids were suppressed, Roman cults mixed with local Celtic gods. Formal Roman worship also existed. Overall, the local people became Romanized to some extent.

Medieval Cumbria: From Chaos to Kingdoms

The medieval period in Cumbria saw big changes. After the Romans left, local leaders fought for control. Then, new kingdoms emerged. Later, the Angles and Vikings arrived, bringing new cultures and conflicts.

Early Medieval Cumbria: After the Romans (410–1066)

Warring Tribes and the Kingdom of Rheged

When the Romans officially left Britain in 410 AD, Cumbria was already mostly independent. The Roman presence was mainly military, so their departure didn't cause huge changes. Local warlords likely filled the power vacuum. They fought for control over different regions, including one called Rheged. We don't know much about post-Roman Cumbria's political and social life.

This period is often called the "Dark Ages" because there's little archaeological evidence and unreliable written sources. Some famous figures like King Arthur are debated as historical or legendary. Arthurian legends are linked to Cumbria.

After the Romans, a leader named Coel Hen might have been a "High King" of Northern Britain. He supposedly ruled from York.

The Roman withdrawal created a power vacuum. Local warlords fought each other, raiding and defending. By the end of the 6th century, some had gained power and formed larger kingdoms. Rheged was one of these.

The exact size of Rheged is debated. Some historians believe it covered the Solway plain and Eden valley. Others think it included parts of Scotland, Lancashire, and Yorkshire. Its center might have been in the Lyvennet Beck valley or at Carlisle.

We know little about Rheged's kings, mostly from poems by Taliesin. He was a poet for Urien, King of Rheged. Urien fought against the Angles from Bernicia. He was betrayed and killed around 585 AD. A big battle followed, where the British were defeated. This likely led to Rheged paying tribute to the Northumbrians.

Christian Saints

The early spread of Christianity in Cumbria is also unclear. Saints like Saint Patrick, Saint Ninian, and Saint Kentigern are linked to the region. It's hard to tell if these links show a continuous Celtic Christian presence or later revivals. There's no definite evidence of 6th-century stone churches.

Life in Early Medieval Cumbria

Despite the fighting, the 5th and 6th centuries might not have been a time of great economic hardship in Cumbria.

The Angles: Northumbrian Rule (c. 600–875)

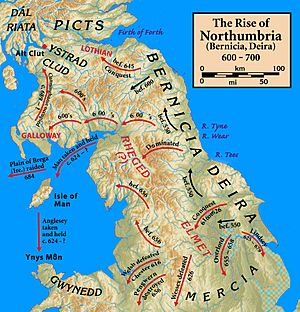

The 7th century saw the rise of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria. By 604, Northumbria had taken over Rheged. The exact date and extent of Anglo-Saxon settlement are debated. Evidence comes from place-names, sculptures, and blood-group studies, which are all open to interpretation.

Northumbrian power stretched to the Irish Sea. How much Rheged was involved is unclear. Northumbrian ambitions were checked by a defeat in 685. But Cumbria remained under Northumbrian control.

Around 638 AD, Oswiu, who became King of Northumbria, married Riemmelth. She was a princess of Rheged. This alliance marked the beginning of the end for Cumbrian independence. Angles began to settle in the Eden Valley and along the coasts.

The extent of Anglian settlement is unclear. Place-names suggest Old English names are in lower-lying areas. Some historians believe the Solway and lower Eden valley remained mostly "Celtic." Carlisle kept its old Roman status under Northumbrian rule. Many people continued to speak Cumbric. Exceptions were the upper Eden valley, the eastern edge of Bernicia, the coast, and the south.

King Edwin was supposedly converted to Christianity around 628. Later, Oswiu united three kingdoms by marriage. It's possible Anglian sub-kings ruled at Carlisle.

In 670, Ecgfrith became King of Northumbria. The Bewcastle Cross was erected, showing English runes. Cumbria was a province, but it remained mostly British with its own client-kings.

Church and State

The relationship between the church and state might have ended Northumbrian control. Legend says Cuthbert foresaw Ecgfrith's death. Bede said Northumbrian power declined from 685. But military setbacks were only part of the story. Family struggles and land grants to the church also played a role. Cuthbert received land around Cartmel.

Large church estates became an alternative power base. In Cumbria, monasteries existed at Carlisle, Dacre, and Heversham. Anglian sculptures were found at monastic sites. These crosses were memorials, not grave markers.

The rise of the church and decline of royal power meant Northumbria was too weak to fight the Vikings. By 875, Danish Vikings had taken over Northumbria. Cumbria entered a period of Irish-Scandinavian (Norse) settlement. More Brittonic Celts also arrived from the late 9th century.

Vikings, Strathclyde British, Scots, English (875–1066)

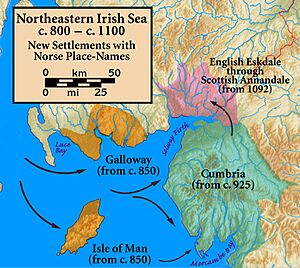

The Norse raided Northumbrian monasteries in the early 800s. By 850, they settled in Scotland's Western Isles, the Isle of Man, and around Dublin. They might have raided or settled in west Cumbria.

The collapse of Anglian authority in Cumbria led to the Norse, Danes, and Strathclyde British filling the power vacuum. Our sources are limited. We rely on place-names, artifacts, and stone sculptures. Historians debate the timing and extent of Viking and Strathclyde influence.

Strathclyde British Settlement

Some historians argue that people from the Kingdom of Strathclyde moved into northern Cumbria. Strathclyde was also called 'Cumbria' at this time. Other historians see it as a Celtic "survival" rather than a "re-colonization." Most of what became Cumbria, south of the Eamont, was untouched by this movement.

This settlement of fellow Christians might have been encouraged by the Anglo-Celtic aristocracy. They might have wanted a counterweight against the Hiberno-Norse. An alliance of Scots, British, and English might have fought the Norse.

This changed when Athelstan became King of England in 927. At Eamont Bridge, kings from across Britain gathered. They included Athelstan, the King of Scots, the King of the Cumbrians, and others. Athelstan received their submission, possibly to form a coalition against the Vikings. This is seen as the founding date of the Kingdom of England. Its northern border was the Eamont river.

However, Strathclyde/Cumbria later joined the Dublin Norse against the English. After the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, Athelstan made peace with the Scots. Scandinavian settlement might have been encouraged in Cumbria by Strathclyde overlords.

In 945, Athelstan's successor, Edmund I, invaded Cumbria. He defeated the last Cumbrian king, Dunmail. The area was given to Malcolm I, King of Scots. But the southernmost areas likely remained English.

Place-names and stone sculptures suggest Scandinavian colonization. It happened on the west coastal plain and in north Westmorland. Warriors who settled here encouraged stone sculptures. But Anglian peasants also survived. Some less successful occupation happened in other lowland areas. This led to place-names with Norse endings. "Southern Cumbria" was also heavily colonized.

The occupation was likely by the Norse between 900 and 950. It's unclear if they came from Ireland, the Isle of Man, or Norway. The settlement's peacefulness is debated. Some suggest peaceful Gaelic-Norse settlement in west Cumbria. Others say Dublin Norse colonized the Cumbrian coast. The route through Cumbria to York was likely used often. In Westmorland, much colonization came from Danish Yorkshire.

There was no organized "Viking" community. It was small groups taking over land. But some argue Scandinavians took over Anglian villages too.

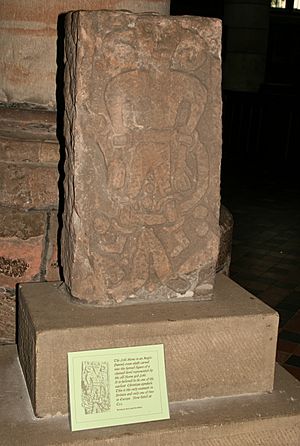

Sculpture evidence is unclear about influences. Some "Viking" crosses might reflect secular or early Christian ideas.

Viking relics include a hoard of coins and silver objects found at Penrith. Other finds were at Hesket and Ormside. Pagan graves were found at Cumwhitton.

The Scots and 'Cumbria'

Some historians suggest that the Cumbrian area was prosperous. It might have had its own kingship, with increasing Scottish influence. This interpretation is debated.

From around 941, Cumbrian/Scottish rule might have lasted about 115 years. Their territory extended south to Dunmail Raise. In 945, Edmund I ravaged Strathclyde/Cumbria and gave it to Malcolm I of Scotland. This might have defined English rule or secured a treaty with the Scots.

In 971, Kenneth II of Scotland raided Westmorland. In 973, Kenneth and Máel Coluim I of Strathclyde gained recognition for an enlarged Cumbria from King Edgar the Peaceful. Westmorland became a buffer zone.

The English and Cumbria

In 1000, the English king, Ethelred the Unready, invaded Strathclyde/Cumbria. After Cnut took the English throne, the north became more unstable. Siward, Earl of Northumbria, a Dane, became a strong leader. He took control of Cumbria south of the Solway between 1042 and 1055. This might have been to counter independent lords or take advantage of Scottish troubles.

Siward helped his kinsman Malcolm III of Scotland in 1054. Malcolm invaded Northumbria in 1061, possibly to regain lost Cumbrian territory. He likely succeeded in regaining Cumberland in 1061. For the next thirty years, Cumbria was under Scottish control.

Malcolm III held Cumberland until 1092. This was partly due to turmoil among English nobles and the disaffection of monks. Other factors included the absence of Earl Tostig and his friendship with Malcolm.

High Medieval Cumbria: Norman Rule and Border Conflicts (1066–1272)

Norman Takeover: William I, William Rufus, Henry I, David I

The Norman takeover of Cumbria happened in two stages. The southern part was taken in 1066. The northern part, the "land of Carlisle," was taken in 1092 by William Rufus.

William I

The Norman conquest of England was slow in the North. This was due to the land's poverty and rebellions elsewhere. Malcolm III's raids, Danish attacks, and English rebels weakened William I's control. Most of Cumbria remained Scottish. It was also a base for outlaws.

William finally controlled Northumbria. His son, Robert Curthose, built Newcastle castle in 1080. This helped clear up banditry.

Domesday

When the Domesday Book was made in 1086, Cumbria was a "no-man's-land." It was not yet conquered by the Normans. Only the southern part, like Furness, was included. It was listed as part of Yorkshire.

William II

William II of England (William "Rufus") saw the need to secure the northern frontier. In 1092, Rufus took over Cumberland. He expelled the local lord, Dolfin. He built Carlisle Castle and sent peasants to farm the land. This takeover aimed to gain territory and defend the northwest. It might have also provoked King Malcolm. Malcolm's last invasion and death followed. This allowed Rufus to hold Cumberland until his death in 1100.

Henry I

Henry I of England brought big changes to Cumbria. He had good relations with Scottish kings. So, he could focus on developing his northern lands. He granted Appleby and Carlisle to Ranulf le Meschin. Ranulf became a strong leader in the northwest.

Henry I visited Carlisle in 1122. He ordered the castle fortified. He created new land holdings called "baronies." These included Copeland and Allerdale. Henry also took direct control of Carlisle. This was partly to manage the silver mine at Alston. He also established the Augustinian priory of Saint Mary at Carlisle. It became Carlisle Cathedral in 1133.

Henry promoted Norman allies. But he also gave secondary roles to local lords. For example, Æthelwold became the first Bishop of Carlisle.

David I of Scotland

After Henry I's death in 1135, England fell into civil war. David I of Scotland supported Henry's daughter, Matilda. David had been a "Prince of the Cumbrians." He believed "Cumbria" (Strathclyde/Cumbria) was under Scottish rule. It stretched to Westmorland and possibly north Lancashire. The Treaty of Durham (1136) gave Carlisle and Cumberland to David.

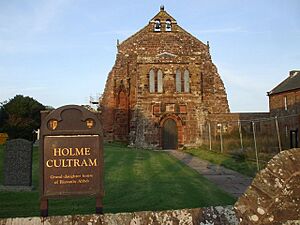

David might have wanted to expand his control in northern England. He fought at the Battle of the Standard. Despite losing, he kept his Cumbrian lands. His son Henry became Earl of Northumberland. This arrangement lasted twenty years. David minted his own coins using Alston silver. He founded Holmcultram Abbey. He kept the north out of the civil war. In 1149, he secured a promise from Henry II of England not to challenge Scottish rule over Carlisle and Cumberland. David died at Carlisle in 1153.

Cumbria under the Early Angevins (1154–1272)

Henry II, 1154–89

When Henry II of England became king in 1154, he took advantage of Scotland's young king, Malcolm IV. Malcolm had inherited Cumbria and Northumbria. He paid homage to Henry for them. But in 1157, Henry demanded and got back control of Cumbria and Northumberland. Malcolm received other lands in return. Relations were friendly, though they argued in Carlisle in 1158.

Henry used this peace to increase royal control. Justices toured the north, taxes were collected, and order was kept. Hubert I de Vaux was given the Barony of Gilsland to strengthen defenses. When William the Lion became Scottish king in 1165, border wars began. Carlisle was besieged twice in 1173–74. But Cumbria was not given to the Scots. The Treaty of Falaise in 1174 formalized peace.

Around this time, the counties of modern Cumbria were formed. Westmorland was created in 1177 from Appleby and Kendal. Copeland was added to Carlisle to form Cumberland in 1177. Lancashire was formed in 1182, including part of South Cumbria.

Richard I and John, 1189–1216

Richard I of England needed money for his crusade. He canceled the Treaty of Falaise for Scottish money. The Scots asked for Cumbria and Northumbria back from Richard and John, King of England, but were refused. John continued to strengthen royal control and collect unpopular taxes.

However, civil war broke out in England in 1215. The new Scottish king, Alexander II of Scotland, supported the English nobles. In return, he was promised Cumbria and Northumberland. A Scottish army marched into Carlisle in 1216–17. John drove them out, but they returned. This ended with John's death in 1216.

Henry III, 1216–72

Henry III of England became king at nine years old. An agreement was made in 1219. The English kept the northern counties. Alexander gained lands in the north, including manors in Cumberland like Penrith and Castle Sowerby.

In 1237, the Treaty of York was signed. Alexander gave up claims to Northumberland, Cumberland, and Westmorland. Henry granted him lands in the north, including the Honour of Penrith. This included Penrith, Castle Sowerby, and other manors. The Penrith honor remained Scottish until 1295.

The 13th century was a time of prosperity. Many monasteries flourished, especially Furness Abbey. It became the second richest religious house in northern England. Wool was Cumbria's biggest commercial asset. Sheep were bred on the fells. Wool was carried to Kendal, which became wealthy from the wool trade. Iron was also mined. Forests were used for hunting.

Later Medieval Cumbria: Wars and Fortifications (1272–1485)

The Scottish wars hardened the border. Cross-border cooperation turned into warfare. The English Crown's weak authority led to powerful border families like the Percies and Nevilles. They became the effective law. Smaller groups engaged in banditry. Families built peel towers and bastle houses for defense. Scottish raids caused more damage than the Wars of the Roses in Cumbria.

The Scottish Wars of Independence

Peace between England and Scotland ended in the late 13th century. Edward I of England wanted to control Scotland. He took back manors granted in 1237. In 1292, he put John I of Scotland on the Scottish throne. Edward also took direct control of Carlisle. However, war with France in 1294 led Balliol to break the agreement. In 1296, he invaded Cumbria, but Carlisle held out. Edward defeated him and took over Scotland.

Resistance came from William Wallace in 1297. Carlisle Castle was besieged again. Robert the Bruce supported Edward in ending Wallace's rebellion. Edward's death in 1307 and English internal disputes allowed Robert the Bruce to establish himself in Scotland. After the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, border warfare moved to the English side. The Bishop of Carlisle made private deals with the Scots to protect his lands. A 300-year period of raids followed, undoing economic progress.

Two early raids in 1316 and 1322 by Bruce were very damaging. The Abbot of Furness Abbey tried to bribe Bruce to spare his abbey. Bruce took the bribe but still ransacked the area. Land values dropped sharply.

The system of Wardens of the Marches began. These were experienced military men from powerful local families. They ran private armies. They dealt with disputes and criminal cases using "March law." They recognized special border tenant rights in return for military service.

Border families engaged in warfare and raiding. Lesser bandits often had protection from greater lords. So, in the 14th century, more castles and fortified houses were built. These included peel towers and bastle houses. Carlisle authorities complained their city's defenses were neglected.

The Church also suffered raids. Monks of Holm Cultram built a fortified church. Furness Abbey and Lanercost Priory were damaged. The Bishop of Carlisle even joined a raid into Scotland to get money to fortify his home. Paying protection money was another way to stop the Scots. Carlisle paid £200 in 1346.

Edward III and the Hundred Years' War

The defeat at Bannockburn and an unsatisfactory treaty led Edward III of England to back those who lost land in Scotland. The Second War of Scottish Independence lasted from 1332 to 1357. It boosted Edward's standing but ended with an independent Scotland. During this time, northern counties were invaded. Carlisle paid protection money in 1346.

By 1337, Edward was involved in the Hundred Years' War with France. The Scots sided with France. Carlisle was besieged in 1380, 1385, and 1387. Appleby was almost destroyed in 1388. Most peel towers and warning beacons were built during these years.

The Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses had some impact on Cumbria. The rivalry between local landowners fed into court politics. The two main families were the Percies and the Nevilles.

The Nevilles were promoted by Richard II of England to balance the Percies. Ralph Neville became Earl of Westmorland in 1397. The Cliffords, based at Appleby, feared the Nevilles and supported the Lancastrian Percy interest.

Both Percies and Nevilles backed Henry Bolingbroke to become King Henry IV of England in 1399. Percy power was restored, and Nevilles were rewarded. But the Percies rebelled in 1402 and lost their position. The Earl of Westmorland was rewarded for fighting against them.

This local feud became a national blood-feud in 1455. Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, joined the Yorkist cause.

In the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), Edward IV did not raise troops in Cumbria. The northern counties were mostly Lancastrian. But Yorkist victories led to Neville influence in Carlisle and Appleby. Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick became sheriff of Westmorland. Later, Richard III of England received most of the Neville lands in Cumbria.

Most northern nobles backed Richard's bid for king in 1483. But at the Battle of Bosworth Field, Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland, failed to support Richard.

Despite Cumbrian involvement, Scottish raids and border feuding caused more damage to the region than the Wars of the Roses.

Early Modern Cumbria: Tudors and Stuarts (1485–1714)

Cumbria during the Tudor period saw much turmoil. The English Crown responded to local clans (the border reivers), the English reformation, Catholic rebellions, and war with the Scots. Royal power grew at the expense of local families. These issues were all connected.

The Border Reivers

For 300 years until 1603, unrest was constant due to the Border Reivers. They were known for strong family ties, forming clan-like groups. They were semi-independent and loyal to their family name, not the king. In north Cumbria, prominent clans included the Grahams, Hetheringtons, and Armstrongs.

The Reivers lived by raiding cattle and sheep across the border. They even looted their own king's armies. Raiding became so violent that wealthier families built bastle houses or pele towers. These were fortified homes with space for livestock. Many are still seen in north Cumbria.

To deal with this, English and Scottish monarchs appointed "wardens of the marches." These powerful local leaders enforced "March law." North Cumbria was the English West March.

Despite being on the tough border, Cumbria didn't suffer as badly as expected. The area around Bewcastle and the border itself suffered. But the West Cumbrian Plain and Eden Valley were relatively untouched. Carlisle Castle and other strongpoints helped direct reivers away.

Local families like the Dacres and Cliffords were wardens. Many were involved in reiving themselves. Both English and Scottish governments encouraged reivers. Their light cavalry were useful in conflicts.

The reiver problem worsened in the late 16th century. Increased taxes led to higher rents, breaking ties between landlords and tenants. Many border families remained Catholic after the Reformation. Reiving only stopped when the border effectively dissolved with the Union of the Crowns in 1603.

The Reformation in Cumbria

The English reformation had little effect in Cumbria. Local lords like the Dacres were strong Catholics. Bishops in the region were not very interested in reform. Cumbria also lacked prosperous towns where Protestantism might take hold.

Lord Dacre, a Catholic, controlled many monasteries in the north. Scottish Catholic influence was also strong. Cumbrian participation in the Pilgrimage of Grace showed people wanted Catholic reform. They disliked the removal of saints' days.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries didn't cause much uproar. The main beneficiaries were royal supporters. Many parishes were left without priests.

Under Queen Mary I, Catholic services were easily restored. There were few Protestant preachers. People were more focused on survival against plague, reivers, and Scots. There was also some ignorance of theology and retention of old superstitions. Parish clergy were few and poorly educated.

In the 1560s, the Bishop of Carlisle found little resistance to reform. The real problem was with the common people, who had other concerns.

Early Tudor Cumbria (1485–1558)

English policy towards Scotland often involved stirring up trouble or open warfare. Promoting Protestantism in Scotland was also a Tudor goal. The focus on Mary, Queen of Scots as a Catholic successor to Elizabeth I of England affected Catholic nobles in Cumbria.

Thomas Dacre, 2nd Baron Dacre, a Cumbrian leader, fought for Henry VII. He became an effective Warden of the West March. Dacre and his Cumbrian riders fought at the Battle of Flodden in 1513.

The most notable event was the Battle of Solway Moss in 1542. This happened after James V of Scotland refused to follow Henry VIII's Reformation policy. Local gentry, led by Thomas Wharton, defeated the Scots. Wharton was one of the Tudors' "new men" meant to lessen the power of local nobles.

After the Anglo-Scottish war of the 1540s, the border was finally defined. A commission in 1552 drew a straight line, marked by a trench and dike, in the Debatable land.

The Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion in 1536/37 had many causes. These included high prices, poor harvests, loss of charity from dissolved monasteries, and resentment against landlords. In Cumbria, greedy landlords were a main factor. The Dacres and Cliffords' animosity also fueled trouble. Rebels reopened monasteries. Eventually, the two main noble families united. Henry Clifford, 1st Earl of Cumberland, with Dacre help, ended the siege of Carlisle. Most Cumbrian gentry and clergy didn't support the rebels.

Cumbria under Elizabeth I (1558–1603)

In May 1568, Mary, Queen of Scots, arrived at Workington Hall. She then traveled to Cockermouth. Richard Lowther, the deputy-Warden, escorted her to Carlisle Castle. There were rumors that Catholic nobles wanted to rescue her. Henry Scrope, 9th Baron Scrope of Bolton, moved her to Bolton Castle to prevent her escape.

The Rising of the North happened after Mary was moved further south. Local and personal reasons played a role for the nobles involved. These included Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland, Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland, and Leonard Dacre. The main instigators were lesser gentry and unhappy Catholics.

The Earl of Westmorland felt pressured by new church payments. He also disliked Protestantism and lost authority to new officials. Dacre's motives seemed to be about preventing his inheritance from falling to the Duke of Norfolk.

Increase in Royal Power

Few people joined the 1569 rebellion. This showed the northern earls' weakness after the Pilgrimage of Grace. It also showed the growing power of the Elizabethan state. The Crown had more effective military might, especially artillery. Carlisle Castle was kept by the Crown and modernized.

Northern nobles struggled financially. Border duties, civil wars, and loss of heirs weakened their power. The system of dividing inheritance and multiple tenancies allowed them to raise forces. But this meant harsh rents, causing resentment among tenants.

The Tudor regime inherited Richard III's northern lands. Elizabeth also put her own local gentry in power. For example, most Dacre lands went to the Crown until 1601. Elizabeth became "the dominant landowner on the Cumbrian border."

Georgian and Victorian Periods: Industry and the Lake District (1714–1901)

This period saw the rise of heavy industry in Cumbria. It also saw the "making" of the Lake District as a famous tourist area.

Heavy Industry

Cumbria was home to important industrial sites:

- Barrow Hematite Steel Company

- Vickers Shipbuilding Engineering Limited

- Seaton Iron Works

The Making of the "Lake District"

For many, Cumbria is the Lake District. Some argue that Cumbria has always had a "perceived unity." This was long before tourists arrived.

Early Travelers

Early travelers to the Lake District often didn't live there. Their views were shaped by other places they knew. Daniel Defoe in 1726 called the mountains "formidable" and useless. This was a pre-Romantic view.

Celia Fiennes (1684–1703) was more factual. She described the "desart and barren rocky hills" of Westmorland. Thomas Pennant was more interested in mines than lakes. Arthur Young focused on farming and social conditions.

The Picturesque Movement

By the late 18th century, attitudes to mountain scenery changed. This was partly due to upper-class British travelers returning from the "Grand Tour." They had crossed the Alps and seen paintings by famous artists. This led to a greater appreciation for rugged scenery. The idea of a "Noble savage" and a life away from industrialization also grew. When the Napoleonic Wars stopped travel to Europe, people looked for Romantic scenery in England. The Lake District was perfect.

Two local clergymen helped promote the Lakes. Dr. John Dalton spoke of "savage grandeur" that charmed the mind. Dr. John Brown compared Derwentwater favorably to Dovedale. This persuaded Thomas Gray to visit in 1769. Gray emphasized the Miltonic "Paradisical" aspects of the Lakes.

The first guidebook writer was Thomas West (1778). He promoted "static, pictorial sense of landscape." He also highlighted the Englishness of the Lakes. William Gilpin (1786) taught people "how to look" at the views. Both recommended using a Claude glass to view the "best" scenes.

William Hutchinson focused on history and topography. He and friends fired cannons on Ullswater to hear echoes. This showed an egoistical focus on personal sensations, not the landscape itself. Critics called the Picturesque an "appalling distortion of perception." It reduced the world to a "scribbling-pad for man."

Criticism of this view began in the 1790s. Writers argued against "improving" nature. A "new Picturesque" emerged, aiming to blend buildings with the natural landscape.

The "Lake Poets" and Other Writers

The "Lake Poet School" was a misleading term. It wasn't a cohesive group. Its main members were William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Robert Southey. Dorothy Wordsworth inspired her brother William.

Wordsworth settled at Dove Cottage in Grasmere. The Lakes became central to his identity as a poet. He didn't "discover" the Lakes, but he became a key attraction. His poetry explored the link between humans and nature. He disliked distorting nature for art.

Wordsworth's early political ideas led him to use "plain language" and focus on the "common man." His third innovation was exploring his own mind. His poem The Prelude was about "the growth of my own mind."

Wordsworth cared deeply about family and community. He worried about social changes affecting poor people. He disliked changes that went against nature, like planting straight lines of trees or building railways. He also disliked grand houses built by industrialists. In 1810, he published his Guide to the Lakes. It aimed to preserve the Lakes. The Guide was very popular and influenced building and gardening for a hundred years.

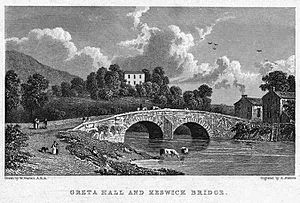

For other writers, the Lakes were less appealing. Samuel Taylor Coleridge moved to Greta Hall in 1800. He saw the landscape's "Gothic elements," suggesting psychological horror. The Cumbrian climate worsened his health. He left in 1804.

Robert Southey lived at Greta Hall from 1803 to 1843. He was mostly a prose writer. He became a conservative, seeing the Lakes as a symbol of the nation.

The second generation of Romantic poets found a different reality. Percy Bysshe Shelley lived in Keswick in 1811. He found Southey's views changed and the Lakes "despoiled." John Keats had a similar experience in 1818. He found Wordsworth's house full of fashionable people. He moved to Scotland for inspiration. Lord Byron ridiculed the older Lake Poets.

John Wilson lived near Windermere. His poetry showed a physical response to the Lakes. He emphasized companionship and energy.

Harriet Martineau settled near Ambleside in 1845. She focused on the Lakes' connection to the outside world. She supported improved sanitation and railways. Her guide to the Lakes (1855) was factual.

Thomas De Quincey moved into Dove Cottage in 1809. His worship of Wordsworth turned sour. He got to know the local dalesfolk better. He used the Lakes to fuel his dreams and imagination.

John Ruskin settled at Brantwood in 1871. He sought a restful escape. His weariness resonated with visitors. Ruskin became the "new Sage of the Lakes." His scientific approach to rocks and water aimed to teach people how to react morally.

Lake Painters

There wasn't a "Lake School of Painters." Artists usually stayed briefly. But they helped landscape painting gain acceptance.

Print-makers visited since the 1750s. William Bellers produced early images of Derwentwater and Windermere. Thomas Smith emphasized the Lakes' wildness.

Joseph Farington's paintings were more accurate. He helped establish the Lake District as a "northern Arcadia" among London painters. Other painters included Thomas Gainsborough and J. M. W. Turner.

J. M. W. Turner visited in 1797. His paintings captured the elemental forces of the Lakes. He took a mythic view, emphasizing "fragility, transience and triumphant returning."

John Constable visited Windermere in 1806. He produced many sketches and watercolors. These helped his artistic development.

William Green lived in Ambleside. He accurately depicted the land and architecture. He produced The tourist's new guide (1819).

Later, painters like Peter De Wint focused on Christian themes. 19th-century painters followed Ruskin's ideas. They did detailed studies of nature. This led to the "Romantic cult of the sketch." Landscape realists like Atkinson Grimshaw were linked to the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Early Tourism

Early tourists came to the Lakes for antiquity, aesthetics, and science. But after 1790, these motives became simpler. People sought thrills and pleasure.

Writings and paintings drew people to see the locations. Stories like Mary Robinson's brought tourists to Buttermere. They also came to see regattas and curiosities at Peter Crosthwaite's museum. Crosthwaite was the "first local man to see just how lucrative the tourist trade might become."

Fellwalking began as a pastime for the wealthy. It then spread to all classes. With industrialization, there was a desire for working-class people to connect with nature. The Lakes offered fresh air and exercise.

Mountaineering also started with the wealthy and spread. The Alpine Club used the Lakes for training. Lack of snow led to rock-scrambling and rock climbing. Climbers were more interested in challenging nature than communing with it. Pioneers like Owen Glynne Jones and Walter Parry Haskett Smith established new routes.

The Birth of Conservation

Wordsworth is considered a founder of the ecology and landscape conservation movement. He believed buildings should harmonize with their surroundings. His own gardening work showed this. He designed his villa to be smaller than those built by industrialists.

Wordsworth fought against railway expansion from 1844. He argued railways would destroy the countryside and bring in crowds. He believed the Lakes were "national property."

Ruskin also fought against railway extensions. The plan to dam Thirlmere for Manchester's water supply was a big issue. Hardwicke Rawnsley, a future co-founder of the National Trust, was torn. He saw the need for water but also for preserving the Lakes. The scheme passed in 1879. The changes to Thirlmere were not popular.

The Thirlmere decision led Rawnsley and others to form the Lake District Defence Society in 1883. This organization fought for access and conservation. In 1895, Rawnsley, Octavia Hill, and Sir Robert Hunter set up the National Trust to acquire and manage land.

20th Century: Modern Cumbria is Formed

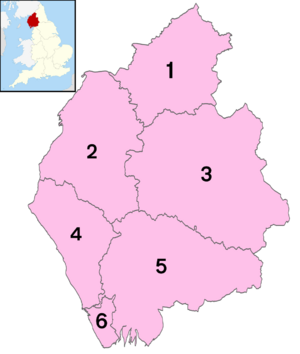

The county of Cumbria was created in April 1974. It combined the administrative counties of Cumberland and Westmorland. Parts of Lancashire (north of the Sands) and the West Riding of Yorkshire were also added.

- 1910 Ais Gill rail accident

- 1913 Ais Gill rail accident

- World War II

- Windscale fire

- 1995 Ais Gill rail accident

21st Century: Recent Events

2000–2010

In the 2001 UK Census, Cumbria had a population of 487,607 people. It was one of the least diverse regions. Most people (99.3%) identified as 'White'.

On January 8, 2005, severe flooding hit northern Cumbria. It was the worst flooding in living memory until 2009. Carlisle was the most affected city. Over 3,000 properties were damaged. 60,000 homes lost power. Some areas were under 7 feet of water. Rivers like the Eden and Derwent burst their banks. The damage cost £250 million.

On February 23, 2007, a Virgin Trains West Coast train derailed in the Grayrigg derailment. This was caused by a defective set of points. One person was killed, and many were injured. Richard Branson, Virgin's owner, said that if the train had been older, the casualties would have been much worse.

The 2009 Cumbria earthquake happened on April 28, 2009. It was a magnitude 3.7 earthquake. Its center was about 8 km (5 miles) under Ulverston. Residents in Lancashire felt the tremor for 5–10 seconds.

On November 19, 2009, parts of Cumbria received more rainfall than a whole winter month. This intense rain broke national records. The worst damage was in Cockermouth and Workington. Water rose almost 3 meters (10 feet) in some places. Many Lake District lakes overflowed. Several bridges collapsed. A police officer, Bill Barker, died when a bridge collapsed in Workington.

Several overseas events also affected the county. The War in Afghanistan claimed the lives of three Cumbrians. The Iraq War saw the deaths of two Cumbrian servicemen.

Timeline

| c. 11,000 | Ice sheets melt, changing the landscape. |

| c. 8,000 | Mesolithic hunter-gatherers settle coastal areas. |

| c. 6,000 | The Langdale Axe Factory begins making stone tools. |

| c. 3,200 | Construction of Castlerigg Stone Circle begins. |

| c. 1,500 | The Langdale Axe Factory starts to decline. |

| c. 50–59 | First rebellion by Venutius against Cartimandua fails. |

| 69 | Second rebellion by Venutius; he gains control of the Brigantian kingdom. |

| 71 | Roman conquest of the Brigantes begins. |

| 78 | Agricola advances in Cumbria, setting up garrisons. |

| 79–80 | More military campaigns by Agricola. |

| 122 | Building of Hadrian's Wall begins. |

| 142 | Antoninus Pius abandons Hadrian's Wall. |

| 164 | Hadrian's Wall is reoccupied by Roman forces. |

| c. 400 | Romans begin withdrawing troops to Europe. |

| 410 | Official end of Roman Britain; Coel Hen becomes 'High King of Northern Britain'. |

| c. 420 | Coel Hen dies; Ceneu takes over Northern Britain. |

| c. 450 | Ceneu dies; Rheged is created by Gwrast Lledlwm. |

| c. 490 | Gwrast Lledlwm dies; Rheged is given to Merchion Gul. |

| 535 | Merchion Gul dies; Rheged is divided into North and South. |

| 559 | Catraeth is added to Rheged lands. |

| c. 570 | Cynfarch Oer dies; Urien Rheged becomes King. |

| 573 | Battle of Arfderydd; Caer-Guenddolau added to Rheged lands. |

| c. 585 | Battle of Ynys Metcaut; Urien is killed; Owain map Urien becomes King. |

| c. 597 | Owain map Urien is killed. |

| c. 616 | Angles of Bernicia enter Rheged. |

| c. 638 | Riemmelth, Princess of Rheged, marries Oswiu, Prince of Northumbria. |

| 685 | St Cuthbert is granted land around Carlisle and Cartmel. |

| 875 | Danes sack Carlisle. |

| c. 925 | Norse people arrive in Cumbria. |

| 927 | 12 July: The Eamont Bridge Conference takes place between kings. |

| 945 | Edmund I defeats Dunmail and gives Cumbria to Malcolm I of Scotland. |

| 1042–55 | Siward of Northumbria takes over Cumbria south of the Solway. |

| 1092 | William II of England restores Cumbria to England. |

| 1098 | Ranulf le Meschin, 3rd Earl of Chester is granted Appleby and Carlisle. |

| 1122 | Henry I of England visits Carlisle. |

| 1133 | Carlisle Cathedral is founded. |

| 1136 | Stephen, King of England is forced to give Cumbria to David I of Scotland. |

| 1157 | Henry II of England regains Cumbria. |

| 1165 | Border wars begin. |

| 1177 | Counties of Cumberland and Westmorland are created. |

| 1182 | Lancashire is created, including part of South Cumbria. |

| 1216 | Scots, fighting King John, take Carlisle. |

| 1237 | Treaty of York: Scottish king gives up claim to Cumbria. |

| 1316 | Scottish raids occur along the west coast. |

| 1322 | More Scottish raids; the Abbot of Furness tries to bribe Robert the Bruce. |

| 1380, 1385, 1387/88 | Devastating raids by Scots. |

| 1536/37 | The Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion. |

| 1568 | Mary, Queen of Scots, arrives at Workington Hall. |

| 1569/70 | The Rising of the North rebellion. |

| 1745 | Clifton Moor Skirmish, the last military battle on English soil. |

| 1951 | Lake District National Park is established. |

| 1974 | The modern county of Cumbria is established. |

| 2023 | County council and district councils are replaced by two new authorities. |

See also

- Cumbria County History Trust

- Kingdom of Strathclyde

- List of Cumbria-related topics

- List of monastic houses in Cumbria

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |