Langdale axe industry facts for kids

The Langdale axe industry was a special place where people made stone tools a very long time ago. It was located in Great Langdale in England's beautiful Lake District. This happened during the Neolithic period, which started around 4000 BC in Britain. The Neolithic period is also known as the New Stone Age.

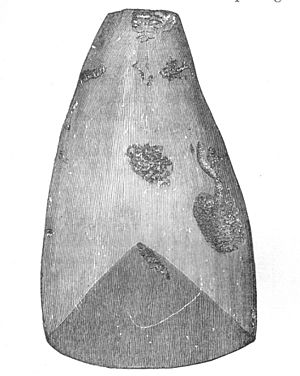

Archaeologists, who study ancient times, first found clues about this axe-making place in the 1930s. Later, in the 1940s and 1950s, people like Clare Fell searched more carefully. They found many unfinished axes, rough shapes, and blades. These were made by knapping, which means carefully chipping away at large rocks. The rocks were found on the mountainsides, often in piles of loose stones called scree. Sometimes, they might have even dug for the rock.

They also found hammerstones, which are rocks used for hitting and shaping other stones. Other small stone pieces, like flakes, were also found. These are all signs of a busy tool-making workshop!

The Langdale area had a special type of rock called fine-grained greenstone or hornstone. This rock was perfect for making strong, smooth stone axes. These axes have been found all over Great Britain. The greenstone was taken from the scree slopes on mountains like Harrison Stickle and Pike of Stickle. Scientists are still studying how big and busy these ancient axe factories were.

The special rock used for these axes comes from a narrow line of the highest peaks in the area. Other places on mountains like Harrison Stickle and Scafell Pike also show signs of axe making. Rough axe shapes and flakes have been found high up on these mountains.

Where Langdale Axes Were Found

The stone axes made in Langdale have been discovered at ancient sites all across Britain and Ireland. Many of these axes have been found in the East of England, especially in Lincolnshire.

Francis Pryor, an archaeologist, thinks these axes were very special in that region. He believes they might have had a religious meaning, perhaps because they came from high mountains. He compares this to other ancient flint mines. Most of these mines were also in high places, except for Grime's Graves, which had very high-quality flint.

About 27% of all the polished stone axes found in the UK came from the Langdale area. This is amazing because there were more than 30 other places where stone for axes was found, from Cornwall to Scotland and Ireland.

Whether they were religious objects or not, these axes must have been very valuable. They were "traded" or moved over long distances. Some axes look like they were used a lot, while others seem brand new. This might mean they were sacred objects or a way to show off wealth.

However, many axes were definitely used as tools. Their shape suggests they were attached to wooden handles. They were likely used to clear forests for farming and to cut wood for building houses and boats.

Francis Pryor also found a flint axe near Peterborough that had beautiful swirling patterns. But these patterns were weak spots, making the axe very fragile. Even so, someone spent a lot of time making it. This shows that some axes were valued for their beauty, not just for being practical tools. The Langdale axes were both beautiful and useful, and they traveled far from where they were made.

Axe Making in Ancient Times

The Langdale industry was just one of many places where hard stone was dug up to make polished axes. The Neolithic period was a time when people started to settle down and farm. They needed axes to clear forests for crops and animals. Axes were also important for cutting wood to build homes, boats, and other structures.

Flint was probably the most common material for tools. It was found in many flint mines in places like Grime's Graves, Cissbury Ring, and Spiennes. Small blades made from flint could also be used as knives, arrowheads, and other sharp tools.

Other strong stones were also used. For example, rocks from Penmaenmawr in North Wales were used for axes. Similar axe-making sites to Langdale have been found there. Many other places across the country might have made axes, including Tievebulliagh in County Antrim, sites in Cornwall, Scotland, and the Charnwood Forest in Leicestershire. It's also thought that "bluestone" axes were sent from the Preseli Hills in Pembrokeshire. Axe making was also common in other parts of the world, like the Mount William stone axe quarry in Australia, which used similar rock until more recent times.

Museums have many different types of polished stone tools. It's hard to know exactly where all the rocks came from. To find out, a small piece of the tool has to be removed, which museums often don't want to do. Also, the large rocks or anvils used to polish the axes are rare in Britain, but more common in France and Sweden.

Scientists have used Radiocarbon dating to study the Langdale stone axe factory. They believe it was active for about 1,000 years during the Neolithic period.

Some experts think that the people who made these axes might also have built some of the first stone circles, like the one at Castlerigg stone circle.

Protecting These Ancient Sites

The Langdale axe-making sites are high up in the mountains and on rough land. This has helped protect them from damage that happens in places where people live. However, many walkers visit Great Langdale. Some people have taken axes from the sites, even though it's best to leave them where they are found. Walking can also accidentally damage the scattered stone pieces.

In the 1980s, there was an effort to protect these sites as ancient monuments. But it was hard to do because there weren't good maps of the area. Now, English Heritage is thinking about how to manage these sites. They are paying special attention to where footpaths are placed to avoid damaging the axe-making areas.

Since the 1990s, a project called "Fix the Fells" has been repairing eroded paths in the Lake District, including Great Langdale. The National Trust is a main partner in this important work.

You can see Langdale axes in museums in Cumbria, like the Kendal Museum and Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery in Carlisle. They are also in other collections, such as the British Museum.

|