James I of Scotland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids James I |

|

|---|---|

16th-century portrait of James

|

|

| King of Scots | |

| Reign | 4 April 1406 – 21 February 1437 |

| Coronation | 21 May 1424 |

| Predecessor | Robert III |

| Successor | James II |

| Born | possibly 25 July 1394 Dunfermline Abbey, Fife, Scotland |

| Died | 21 February 1437 (aged around 42) Blackfriars, Perth, Scotland |

| Burial | Perth Charterhouse |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Stewart |

| Father | Robert III of Scotland |

| Mother | Annabella Drummond |

|

Events

|

|

James I (born in late July 1394 – died 21 February 1437) was the King of Scots from 1406 until he was killed in 1437. He was the youngest of three sons born to King Robert III and Annabella Drummond at Dunfermline Abbey.

His older brother, David, Duke of Rothesay, died under suspicious circumstances while held by their uncle, Robert, Duke of Albany. James's other brother, Robert, died young. People worried about James's safety in the winter of 1405-1406, so plans were made to send him to France.

In February 1406, James had to hide in the castle on the Bass Rock after his guards were attacked. He stayed there until mid-March, then boarded a ship for France. But on 22 March, English pirates captured the ship and took the prince to Henry IV of England. King Robert III died on 4 April, making 11-year-old James the uncrowned King of Scots. He would not be free for another eighteen years.

James received a good education while held at the English Court. He learned a lot about how the English government worked and respected King Henry V. James even joined Henry in his military campaigns in France between 1420 and 1421.

In February 1424, James married Joan Beaufort, a cousin of the English King. He was released in April that same year. James's return to Scotland was not fully popular because he had fought alongside Henry V in France, sometimes against Scottish soldiers. Noble families also faced higher taxes to pay for his release, and they had to provide family members as hostages.

James enjoyed sports, reading, and music. He also strongly wanted to bring law and order to Scotland. However, he sometimes applied these rules unfairly. To strengthen his power, James attacked some of his nobles, starting in 1425 with his own relatives, the Albany Stewarts. This led to the execution of Duke Murdoch and his sons.

James also arrested other powerful nobles, like Alexander, Lord of the Isles, in 1428, and Archibald, 5th Earl of Douglas, in 1431. The money meant for his ransom was instead used to build Linlithgow Palace and other grand projects. In August 1436, James failed to capture Roxburgh Castle from the English. He was killed in Perth on the night of 20/21 February 1437 during a failed takeover attempt by his uncle, Walter Stewart, Earl of Atholl. Queen Joan, though hurt, escaped and reached her son, now King James II, in Edinburgh Castle.

Contents

Early Life and Capture

James was likely born in late July 1394 at Dunfermline Abbey. He spent most of his early childhood there, cared for by his mother, Annabella Drummond. When James was seven, his mother died in 1401. A year later, his older brother, David, Duke of Rothesay, probably died in Falkland Castle while held by their uncle, Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany.

Prince James was now the next in line to the throne. This meant he was the only person stopping the royal family line from shifting to the Albany Stewarts. In 1402, Albany and his ally, Archibald, 4th Earl of Douglas, were cleared of any involvement in Rothesay's death. This allowed Albany to become the king's lieutenant again.

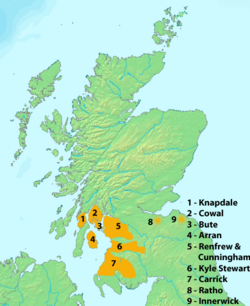

In December 1404, King Robert III gave James control over royal lands in the west of Scotland, in Ayrshire and around the Firth of Clyde. This protected these lands from outside interference and gave the prince a base of power. By 1405, James was under the care of Bishop Henry Wardlaw of St Andrews on Scotland's east coast.

There was growing tension with the Douglas family. In February 1406, Bishop Wardlaw released James to Earl of Orkney and Sir David Fleming. They traveled into Douglas territory, possibly to show royal support for their own interests. This angered James Douglas of Balvenie and his supporters. They attacked, killing Fleming, while Orkney and James escaped to the Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth.

They stayed there for over a month before boarding a ship bound for France. On 22 March 1406, an English ship captured them. James became a hostage of King Henry IV of England. King Robert III learned of his son's capture at Rothesay Castle and died soon after, on 4 April 1406. He was buried at Paisley.

King in Captivity

James, now the uncrowned King of Scots, began an 18-year period as a hostage. Meanwhile, Albany became the governor of Scotland. Albany took control of James's lands, leaving the king without income or the symbols of his position. Records referred to James simply as 'the son of the late king'.

James was treated well by Henry IV and received a good education. He was able to observe how Henry ruled and controlled his kingdom. James kept in touch with his kingdom by receiving visits from nobles and sending letters.

When Henry IV died in 1413, his son, Henry V, immediately ended James's freedom. He held James in the Tower of London with other Scottish prisoners, including James's cousin, Murdoch Stewart.

By 1420, James's standing at Henry V's court improved. He was seen more as a guest than a prisoner. James became useful to Henry in 1420 when he joined the English king in France. His presence was used against Scottish soldiers fighting for the French. After the English captured Melun, a town near Paris, the Scottish soldiers were executed for treason against their own king (James).

James attended Catherine of Valois's coronation in February 1421 and was honored by sitting next to the queen. In March, Henry and James toured English towns to show strength. James was knighted on Saint George's Day. By July, they were back fighting in France. James seemed to approve of Henry's leadership and his desire to rule France. Henry made James a joint commander at the siege of Dreux in July 1421.

Henry V died in August 1422. In September, James was part of the group that took the English king's body back to London.

The council ruling for the young King Henry VI wanted James released quickly. In 1423, they tried to negotiate his release, but the Scots, influenced by the Albany Stewarts, didn't respond much. Archibald Douglas, Earl of Douglas, was a powerful figure in Scotland. Despite his role in James's brother's death, Douglas was able to work with the king.

From 1421, Douglas had been in regular contact with James, and they formed an important alliance in 1423. Pressure from those who wanted the king back likely forced Murdoch, who was now Duke of Albany, to agree to a meeting in August 1423. There, it was decided to send a group to England to negotiate James's release.

James's relationship with the House of Lancaster changed in February 1424 when he married Joan Beaufort. She was a cousin of Henry VI. A ransom agreement of £40,000 was made at Durham on 28 March 1424. James put his own seal on the agreement. The king and queen, with English and Scottish nobles, arrived at Melrose Abbey on 5 April. They were met by Albany, who gave up his governor's seal of office.

James's Rule

First Actions as King

Scottish kings in the 15th century often lacked money for the crown, and James was no different. The Albany regency had also faced financial limits. For the nobles, royal support stopped completely after James was captured. Instead, Albany allowed nobles like the Earl of Douglas to take money from customs.

James's coronation took place at Scone on 21 May 1424. At the parliament, James knighted eighteen important nobles, including Alexander Stewart, Murdoch's son. This event was likely meant to encourage loyalty to the king.

Parliament mainly met to discuss how to pay the ransom. James used this opportunity to show his power as monarch. He passed laws to greatly increase the crown's income by taking back favors given by previous kings and guardians. The Earls of Douglas and Mar were immediately affected when their ability to take large sums from customs was stopped.

Despite this, James still needed the support of the nobles, especially Douglas. He started by being less confrontational. An early exception was Walter Stewart, Albany's son. Walter had openly rebelled against his father in 1423. He also disagreed with his father allowing James to return to Scotland.

James arrested Walter on 13 May 1424 and imprisoned him on the Bass Rock. This likely benefited both James and Murdoch. James probably felt he couldn't move against the other Albany Stewarts while Murdoch's brother, John Stewart, Earl of Buchan, and Archibald, 4th Earl of Douglas, were fighting the English in France. Buchan, a leader with an international reputation, commanded a large Scottish army. But both he and Douglas died at the Battle of Verneuil in August 1424, and the Scottish army was defeated. The loss of his brother and the army left Murdoch politically weak.

A Strong and Demanding King

Douglas's death at Verneuil weakened the position of his son, Archibald, the fifth earl. On 12 October 1424, the king and Archibald met at Melrose Abbey. This meeting likely confirmed Douglas's position, but it also showed a shift in power. Important Douglas allies died in France, and some of their heirs changed their loyalty. This helped James strengthen his own position.

James continued to have the support of the Black Douglas family. This allowed him to begin a campaign against Albany and his family. The king's anger towards Duke Murdoch stemmed from the past, as Duke Robert was responsible for his brother David's death. Also, neither Robert nor Murdoch had worked hard to get James released. James likely suspected they wanted the throne for themselves.

Buchan's lands were taken by the crown, not given to the Albany Stewarts. Albany's father-in-law, Duncan, Earl of Lennox, was imprisoned. In December, the duke's main ally, Alexander Stewart, 1st Earl of Mar, settled his differences with the king.

A difficult parliament meeting in March 1425 led to the arrest of Murdoch, his wife Isabella, and his son Alexander. Of Albany's other sons, Walter was already in prison, and James, the youngest, escaped.

James the Fat, Murdoch's youngest son, led a rebellion against the king. This might have given the king the reason he needed to charge the Albany Stewarts with treason. Murdoch, his sons Walter and Alexander, and Duncan, Earl of Lennox, were tried at Stirling Castle on 18 May. A jury of nobles found them guilty of rebellion. The four men were condemned and immediately executed on 24 and 25 May.

James showed a harsh side by destroying his own close family, the Albany Stewarts. This brought three earldoms (Fife, Menteith, and Lennox) back to the crown. An investigation by James in 1424 found problems with how some crown lands had been given away since the time of Robert I. The earldoms of Mar, March, and Strathearn, along with some Black Douglas lordships, were found to have legal issues. Strathearn and March were taken back by the crown in 1427 and 1435. Mar was taken back in 1435 when the earl died without an heir.

James also tried to increase his income through taxes. In 1424, parliament passed a law for a tax to pay off the ransom. £26,000 was collected, but James only sent £12,000 to England. By 1429, James stopped the ransom payments completely. He used the remaining tax money on cannons and luxury goods from Flanders. After a fire at Linlithgow Palace in 1425, funds were also used to rebuild it. This continued until James's death in 1437 and used about one-tenth of the royal income.

Relations with the Church

James showed his authority not only over the nobles but also over the Church. He felt that King David I's generosity to the Church had been too costly for later kings. James also believed that monasteries needed to improve and become stricter communities.

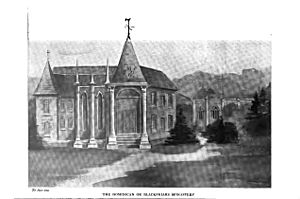

Part of James's plan was to create a group of abbots to oversee the Church. He then set up a Carthusian monastery in Perth to serve as an example for other religious houses. He also tried to influence the Church by having his own trusted clerics appointed as bishops in important areas.

In March 1425, James's parliament ordered all bishops to tell their priests to pray for the king and his family. A year later, parliament made this rule stricter, insisting that prayers be given at every mass, or face a fine. This same parliament passed a law that every person in Scotland should 'be governed under the king's laws and statutes of this realm only'.

Laws were passed in 1426 to limit what church leaders could do, such as traveling to the Roman Curia (the Pope's court) or buying extra church positions. In James's parliament of July 1427, a new law was clearly aimed at reducing the power of church courts.

In 1431, a general council of the Church met in Basel. However, the Pope, Eugenius, and the council disagreed completely. The council, not the Pope, asked James to send representatives from the Scottish church. Two delegates from Scotland attended in November and December 1432. In 1433, James, responding to the Pope's request this time, appointed two bishops, two abbots, and four other church leaders to attend the council.

Twenty-eight Scottish churchmen attended the council at different times from 1434 to 1437. Most high-ranking churchmen sent others to represent them. However, Bishops John Cameron of Glasgow and John de Crannach of Brechin attended in person.

Even during the Basel council, Pope Eugenius sent his representative, Bishop Antonio Altan, to meet with James. The bishop was to discuss the king's controversial laws of 1426, which limited church appointments. The Bishop of Urbino arrived in Scotland in December 1436. It seems James and the papal representative had reached an agreement by mid-February 1437. But James was killed on 21 February, preventing the bishop from finishing his mission.

Dealing with the Highlands

In July 1428, the king called a meeting in Perth to get money for a trip to the Highlands. This was to deal with the Lord of the Isles, who ruled his area almost independently. The council at first didn't want to give James the money, even with support from powerful nobles like the Earls of Mar and Atholl. But they eventually agreed. James wanted to use some force to strengthen royal power in the north.

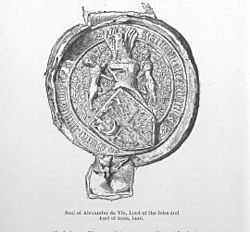

James called the leaders of the Gaelic clans in the north and west to a parliament meeting in Inverness. Around 50 of them were arrested, including Alexander, the third Lord of the Isles, and his mother, Mariota, Countess of Ross, around 24 August. A few were executed, but most were quickly released, except for Alexander and his mother.

While Alexander was held captive, James tried to divide Clann Dòmhnall. He asked Alexander's uncle, John Mór, to take over the clan leadership. But John Mór refused to deal with the king while his nephew was imprisoned. This led to John Mór's attempted arrest and death.

The king needed allies in the west and north. So, he became softer towards the Lord of the Isles. Hoping Alexander would become a loyal servant, James set him free. However, Alexander, likely pressured by his relatives, led a rebellion. He attacked the castle and town of Inverness in spring 1429.

The situation worsened when a fleet from the Lordship was sent to bring James the Fat back from Ireland to make him king. James wanted to ally with Irish clans against the MacDonalds. The English became suspicious of James's plans and tried to bring James the Fat to England themselves. But James the Fat died suddenly before he could become involved. This allowed King James to prepare for a strong attack against the Lordship.

The armies met on 21 June in Lochaber. Alexander suffered a heavy defeat when some clans switched sides. Alexander escaped, probably to Islay. But James continued his attack on the Lordship, taking the strongholds of Dingwall and Urquhart castles in July. The king pressed his advantage, sending an army with cannons to the islands. Alexander likely realized his situation was hopeless and tried to negotiate surrender terms. James demanded and received his complete surrender. From August 1429, the king gave royal authority to Alexander Stewart, Earl of Mar, to keep the peace in the north and west.

The Islesmen rebelled again in September 1431. They defeated the king's men twice. Mar's army was beaten at Inverlochy, and another army was defeated in a fierce battle near Tongue. This was a serious setback for James and hurt his reputation.

In 1431, before the September uprising, the king had arrested two of his nephews, John Kennedy and Archibald, Earl of Douglas. This might have been due to a conflict between John and his uncle, Thomas Kennedy, in which Douglas may have been involved. Douglas's arrest caused tension in the country. James tried to calm things by freeing the earl on 29 September. It's likely the king made Douglas's release conditional on his support at the next parliament. James wanted more money for his campaign against the Lordship.

Parliament was not willing to give James unlimited support. He was allowed a tax for his Highland campaign, but parliament kept full control over the money. The rules parliament attached to the tax showed strong opposition to more conflict in the north. This probably led to a change in policy on 22 October, when the king 'forgave the offense of each earl, namely Douglas and Ross [Alexander]'. For Douglas, this was a formal recognition of his freedom. But for Alexander, it was a complete reversal of the crown's policy towards the Lordship. Four summer campaigns against the Lordship were now officially over, as James's wishes had been blocked by parliament.

Foreign Relations

James's release in 1424 did not mean a new friendly relationship with England. He did not become the obedient king the English council had hoped for. Instead, he became a confident and independent European monarch. The main issues between Scotland and England were the ransom payments and renewing the truce, which would end in 1430.

In 1428, after some defeats, Charles VII of France sent his ambassador to Scotland. He wanted to persuade James to renew the Auld Alliance (the old alliance between Scotland and France). The terms included the marriage of Princess Margaret to Louis, the future dauphin of France, and a gift of the province of Saintonge to James. Charles ratified the treaty in October 1428. With his daughter marrying into the French royal family and owning French lands, James's political importance in Europe grew.

The alliance with France had almost stopped after the Battle of Verneuil. Its renewal in 1428 didn't change much. James took a more neutral stance with England, France, and Burgundy. At the same time, he started diplomatic contacts with many other European countries.

Generally, relations between England and Scotland were quite friendly. An extension of the truce until 1436 helped England in France. The promises made in 1428 of a Scottish army to help Charles VII and the marriage of James's eldest daughter to the French king's son were not fully carried out. James had to be careful with his European responses. England's key ally, the Duke of Burgundy, also controlled the Low Countries, a major trading partner for Scotland. So, James's support for France was limited.

The truce with England ended in May 1436. James's view of the Anglo-French conflict changed after the sides realigned. Talks between England and France broke down in 1435. This led to an alliance between Burgundy and France. France then asked for Scotland's help in the war and for the promised marriage of Princess Margaret to the Dauphin to happen.

In the spring of 1436, Princess Margaret sailed to France. In August, Scotland entered the war. James led a large army to attack the English-held Roxburgh Castle. This campaign proved to be very important. A historical account describes a "detestable split" within the Scottish army. Historians explain that James appointed his young and inexperienced cousin, Robert Stewart of Atholl, as the army's leader. This was ahead of experienced border wardens like the Earls of Douglas and Angus. These earls had strong local interests, and a large army living off the land likely caused resentment.

When English forces came to relieve the castle, the Scots quickly retreated. A chronicle written a year later said the Scots "had fled wretchedly and ignominiously." The defeat, and the loss of their expensive cannons, was a major setback for James. It hurt his foreign policy and his authority at home.

Assassination

The Plot

Walter Stewart was the youngest son of Robert II. He was the only one not given an earldom during his father's lifetime. Walter's elder son, David, died in England in 1434 while held as a hostage for James's release. His younger son, Alan, died fighting for the king in 1431. David's son, Robert, was now Atholl's heir. Both were next in line to the throne after the young Prince James.

James continued to favor Atholl, appointing his grandson Robert as his personal chamberlain. But by 1437, after several setbacks from James, Atholl and Robert probably saw the king's actions as a sign that James would take more of Atholl's lands. Atholl's control over the rich earldom of Strathearn was weak. Both he and Robert would have known that after Atholl's death, Strathearn would return to the crown. This meant Robert's holdings would be the less wealthy earldoms of Caithness and Atholl.

The retreat from Roxburgh Castle made people question the king's control, military skills, and diplomatic abilities. Yet, he was determined to continue the war against England. Just two months after the Roxburgh failure, James called a general council in October 1436 to get more money for war through taxes. The nobles strongly resisted this. Their opposition was voiced by Sir Robert Graham, who had previously served the Albany family and was now a servant of Atholl.

The council then saw an unsuccessful attempt by Graham to arrest the king. Graham was imprisoned and then banished. But James did not see Graham's actions as part of a larger threat. In January 1437, Atholl faced another setback in his own lands. James overturned a decision by the church leaders of Dunkeld Cathedral. The king replaced their chosen leader with his own nephew and strong supporter, James Kennedy.

The Killing of the King

The strong opposition to the king at the general council showed Atholl that James was in a weak position. This may have convinced the earl that killing James was now possible. Atholl had seen how two of his brothers had taken control of the kingdom at different times. As James's closest adult relative, Atholl must have thought that a decisive action by him could also succeed.

The destruction of the Albany Stewarts in 1425 seems to have played a big part in the plot against the king. Their executions and the taking of their lands affected the people who worked on and depended on those estates. Many of these unhappy Albany men found work with Atholl. These included Sir Robert Graham, who had tried to arrest the king three months earlier, and the brothers Christopher and Robert Chambers. Even though Robert Chambers worked for the Royal household, his old ties to the Albany family were stronger.

A general council was held in Perth on 4 February 1437. Crucially for the plotters, the king and queen stayed in the town at their rooms in the Blackfriars monastery. On the evening of 20 February 1437, the king and queen were in their rooms, separated from most of their servants. Atholl's grandson and heir, Robert Stewart, who was the king's chamberlain, allowed his fellow plotters to enter the building. There were about thirty of them, led by Robert Graham and the Chambers brothers.

James was warned that men were there. This gave him time to hide in a sewer tunnel. But its exit had recently been blocked to prevent tennis balls from getting lost. James was trapped and killed.

What Happened Next

The assassins had succeeded in killing the king, but the queen, though wounded, had escaped. Importantly, the six-year-old prince, now King James II, was kept safe from Atholl's control. This was done by removing Atholl's associate, John Spens, from his role as James's guardian. Spens disappeared from records after the killing. The quick reassignment of his positions and lands after the murder suggests he was part of the plot.

In the confusion after the murder, it seemed the queen's attempt to become regent (ruler for the young king) was not certain. No documents from that time suggest widespread horror or condemnation of the murderers. It's possible that if the queen had also been killed and Atholl had gained control of the young king, his attempt to take power might have succeeded.

The queen's small group of loyal supporters, including the Earl of Angus and William Crichton, ensured she kept hold of James. This greatly strengthened her position, but Atholl still had followers. By the first week of March, neither side seemed to be winning. The Pope's envoy called for the council to seek a peaceful solution.

Despite this, by mid-March, Angus and Crichton had likely gathered their forces to move against Atholl. It's also likely that Atholl had gathered his forces to resist. On 7 March, the queen and the council urged the citizens of Perth to resist the forces of the 'felon traitors'.

Atholl and his close supporters only lost power after Earl Walter's heir, Robert Stewart, was captured. Robert confessed to his part in the crime. Walter was taken prisoner by Angus and held at the Edinburgh Tolbooth. He was tried and executed on 26 March 1437, the day after the young James II's coronation. Sir Robert Graham, the leader of the assassins, was captured by former Atholl allies. He was tried at a council meeting at Stirling Castle and executed shortly after 9 April.

Queen Joan's pursuit of the regency likely ended at the council of June 1437. At that time, Archibald, 5th Earl of Douglas, was appointed to act as lieutenant-general of the kingdom.

King James's embalmed heart may have been taken on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Records from 1443 show a payment of £90 to a knight of the Order of St John who had returned it to the Perth Charterhouse from the Island of Rhodes.

James I's Legacy

James was a complex figure. Even though he was a prisoner in England, he received a good education. He became a cultured person, a poet, a skilled musician, and good at sports. Walter Bower, an abbot, listed James's musical talents. He said James was not just an amateur but a master, "another Orpheus." He could play the organ, drum, flute, and lyre. Bower also listed James's sporting abilities, such as wrestling, hammer throwing, archery, and jousting. He described James as eager in "literary composition and writing." His most famous work is his love poem, The Kingis Quair.

Bower generally supported James. However, he and others regretted the fall of the Albany Stewarts. He was also confused by James's desire for land and wealth. While Bower didn't focus on James's negative traits, he hinted that even those close to the king were upset by his harsh rule.

John Shirley's account of James's murder, The Dethe of the Kynge of Scotis, gave an accurate story of Scottish politics. It must have relied on people who knew what happened. The Dethe described James as 'tyrannous' and said his actions were motivated by revenge and greed, rather than for any lawful reason. Shirley agreed with Bower about the Albany Stewarts, writing that their death made the people of the land "sore grutched and mourned."

Later historians, like John Mair and Hector Boece, writing almost a century later, relied heavily on Bower. They described James as an example of a good monarch. Mair praised James, saying he "excelled by far in virtue his father, grandfather and his great-grandfather." Boece called James the "most virtuous Prince that ever was before his days."

Modern historians have different views. E.W.M. Balfour-Melville, in 1936, saw James as a strong supporter of law and order. He noted that James showed that high rank was no excuse for breaking the law. Michael Lynch suggests that James's positive reputation began right after his death when a bishop declared him a martyr. He argues that while pro-James historians praise him, we should also remember that parliament could limit the king's power.

Stephen Boardman believes that by the time of his death, James had succeeded in breaking down the limits on royal authority. Christine McGladdery explains that opposing views were due to "competing propaganda after the murder." Those who were glad the king was dead saw him as a tyrant who attacked nobles without reason and failed to give justice. Others saw him as providing "strong leadership against magnate excesses." They believed his murder was a disaster for Scotland, leading to years of instability. McGladdery also states that James set an example for future Stewart kings by placing "Scotland firmly within a European context."

Michael Brown describes James as a "capable, aggressive and opportunistic politician." His main goal was to establish a strong monarchy free from the conflicts that troubled his father's reign. Brown says James was "capable of highly effective short-term interventions" but failed to achieve complete authority. He writes that James came to power after "fifty years when kings looked like magnates and magnates acted like kings." James succeeded in completely changing the goals of the monarchy. His policy of reducing the power of the nobles, continued by his son James II, led to a more obedient nobility.

Alexander Grant disagrees with James's reputation as the "law giver." He explains that almost all of the king's laws were simply old laws from previous monarchs. Grant concludes that the idea of James's return in 1424 being a turning point for Scots law is an exaggeration. At James's death, only the Douglas family remained among the most powerful noble houses. According to Grant, this reduction in noble power was the most important change of James I's reign.

Family and Children

In London, on 12 February 1424, James married Joan Beaufort. She was the daughter of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset and Margaret Holland. They had eight children:

- Margaret Stewart (1424 – 16 August 1445), married the Dauphin Louis, who would become Louis XI of France, in Tours on 24 June 1436.

- Isabella Stewart (1426 – 1499), married Francis I, Duke of Brittany, on 30 October 1442.

- Joan Stewart (around 1428 – after 16 October 1486); she could not speak. Married before 15 May 1459 to James Douglas, 1st Earl of Morton.

- Alexander Stewart, Duke of Rothesay (born and died 16 October 1430), elder twin of James II.

- James II of Scotland (16 October 1430 – 3 August 1460), married Mary of Guelders.

- Eleanor Stewart (1433 – 20 November 1480), married Sigismund, Archduke of Austria, around 12/24 February 1449.

- Mary Stewart, Countess of Buchan (1434/35–20 March 1465), married Wolfert VI of Borselen in 1444.

- Annabella Stewart (1436–1509), married first on 14 December 1447 to Louis of Savoy, Count of Geneva, and second in 1458 to George Gordon, 2nd Earl of Huntly, before 10 March 1460.

James I in Stories and Art

King James I monument (1814) at Dryburgh Abbey

|

James I has appeared in plays, historical novels, and short stories. Some of these include:

- The Caged Lion (1870) by Charlotte Mary Yonge. This novel shows James I's time as a prisoner in England, mainly in 1421–1422. It highlights his friendly relationship with Henry V of England.

- A King's Tragedy (1905) by May Wynne. This novel covers events from 1436–1437, leading up to James I's assassination.

- Lion Let Loose (1967) by Nigel Tranter. This book covers James I's life from around 1405 until his death in 1437.

- A Royal Poet (1819) by Washington Irving. The author reflects on James I's greatness while visiting Windsor Castle, mentioning his poems "The Kingis Quair" and "Christ's Kirk of the Green".

- James I: The Key Will Keep The Lock (2014) by Rona Munro. This play is part of "The James Plays" series. It focuses on James I's personal growth after his release, his marriage to Joan, and his struggles with noble families to establish his power in Scotland.

See also

In Spanish: Jacobo I de Escocia para niños

In Spanish: Jacobo I de Escocia para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |