Battle of Verneuil facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Verneuil |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

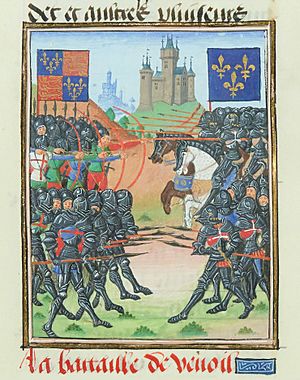

Picture from La Cronicque du temps de Tres Chrestien Roy Charles, septisme de ce nom, roy de France by Jean Chartier, around 1470–1479 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Supported by: |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 14,000–16,000 | 8,000–9,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6,000 killed 200 captured |

1,600 killed | ||||||

The Battle of Verneuil was a major battle during the Hundred Years' War. It took place on August 17, 1424, near Verneuil-sur-Avre in Normandy. The battle was fought between an English army and a combined French and Scottish force. They were also joined by Milanese heavy cavalry.

The English won a very important victory. They even called it a "second Agincourt" because it was so decisive. The battle began with a quick exchange of arrows between English and Scottish archers. Then, 2,000 Milanese heavy cavalry charged the English lines. They broke through the English formation and scattered some of their archers. The Milanese chased the fleeing English soldiers and looted their supply wagons.

Meanwhile, the main English and Franco-Scottish armies fought fiercely on foot. This hand-to-hand combat lasted about 45 minutes. Many English archers rejoined the fight. The French soldiers eventually broke and ran. This left the Scots to fight alone. The English showed them no mercy. When the Milanese cavalry returned, they saw the French and Scottish forces had been defeated. They quickly fled the battlefield.

About 6,000 French and Scottish soldiers were killed, and 200 were captured. The English commander, John, Duke of Bedford, claimed he lost only a few men. However, a Burgundian writer named Jean de Wavrin, who was there, estimated 1,600 English were killed. The Scottish army, led by the earls of Douglas and Buchan, was almost completely destroyed. Both earls died in the battle. Many French nobles were captured, including the Duke of Alençon. After Verneuil, the English were able to make their control in Normandy much stronger.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

In 1424, France was still recovering from the terrible defeat at Agincourt in 1415. The northern parts of France were controlled by the English. This was after King Henry V had conquered Normandy. The Dauphin (the heir to the French throne), Charles, had been disinherited. This meant he was no longer seen as the rightful heir by many. This happened because of the Treaty of Troyes in 1420. After his father, Charles VI, died in 1422, Charles was only recognized as King in the southern parts of France.

A civil war was also happening in France. It was between the Armagnacs, who supported the Dauphin, and the Burgundians, who supported the English. This war showed no signs of ending.

When Henry V died in August 1422, it didn't help the French. Henry's brother, Bedford, continued the war for the young King Henry VI, who was only nine months old. The Dauphin desperately needed more soldiers. So, he looked to Scotland, France's old ally, for help.

The Scottish Army Arrives

The first large group of Scottish soldiers came to France in 1419. There were about 6,000 men led by John Stewart, Earl of Buchan. These soldiers, along with new volunteers, became a key part of the French war effort. By 1420, the "Army of Scotland" was a separate force serving the French King. They proved their skill at the Battle of Baugé in 1421. This was the first major defeat for the English.

However, this hopeful mood ended in 1423. Many of Buchan's men were lost at the Battle of Cravant. At the start of 1424, Buchan brought another 6,500 men. He was joined by Archibald, Earl of Douglas, a very powerful Scottish nobleman. On April 24, this army, with 2,500 men-at-arms and 4,000 archers, arrived at Bourges. This was the Dauphin's main base.

The French also hired 2,000 heavy cavalry from Filippo Maria Visconti, the Duke of Milan. These Milanese soldiers wore strong steel plate armour and rode armored horses. A smaller Milanese cavalry force had helped the French win a battle in September 1423.

The French had also won another battle against the English in September 1423. This made the Dauphin's situation better. The French believed they could defeat a large English army in a big battle. They planned to find the main English army and crush it. After that, Charles VII would be crowned king in Reims.

The French Army

The French army was led by the Count of Aumale. He was a French commander who had won battles against the English and Burgundians. He was with the Viscount of Narbonne. Their army joined with the Scots under the Earl of Buchan. With these strong forces, the French and Scottish army felt sure they could fight the English. They hoped for another great victory like the one at Baugé.

Leading Up to the Battle

In the summer of 1424, the English army, led by Bedford and the experienced Earl of Salisbury, began a siege of the French castle of Ivry. This castle was about 42 kilometers (26 miles) northeast of Verneuil.

The French and Scottish army prepared to march to Ivry to help the castle. Buchan left Tours on August 4 to meet with Aumale and Narbonne. But before their army could reach the castle, it surrendered to the English. The allied commanders were unsure what to do. The Scots and some younger French nobles wanted to fight. But Narbonne and the older nobles remembered Agincourt and didn't want to risk a big battle.

As a compromise, they decided to attack English strongholds near the Norman border. They started with Verneuil in the west. The town was captured using a simple trick. A group of Scots, pretending to be English, led some of their countrymen as "prisoners." They claimed that Bedford had defeated the allies. The town gates were then opened.

On August 15, Bedford heard that Verneuil was in French hands. He and his army marched there as fast as they could. Two days later, as he got closer to the town, the Scots convinced their French friends to fight. It is said that Douglas received a message from Bedford. Bedford joked that he had come to drink with Douglas and hoped for a quick meeting. Douglas replied that he had failed to find the Duke in England, so he had come to find him in France.

On August 16, Bedford sent the Burgundian commander L’Isle Adam and his 1,000-2,000 men away. He sent them back to a siege in Picardy. Historians are still unsure why Bedford sent so many men away just before a battle. Some think it was because the English and Burgundians were starting to distrust each other.

The Battle Begins

How the Armies Lined Up

The French and Scottish army set up their forces about a mile north of Verneuil. They were on an open plain across the road that came out of the Piseux forest. This flat ground was chosen to give the Milanese cavalry the best chance to attack the enemy archers. The Milanese cavalry, led by Caqueran, lined up in front of the French and Scottish soldiers. These soldiers were fighting on foot in one large group. Narbonne's Spanish soldiers and most of the French were on the left side of the road. Douglas and Buchan were on the right. Aumale was in charge overall. However, this mixed army was hard to control as one unit.

When Bedford's English army came out of the forest, he also put his men in one large group. This matched the enemy's setup. The English soldiers were in the middle, with archers on the sides and in front. They had sharpened stakes in front of them. Bedford also placed a small group of 500–2,000 lightly armored men at the back. Some of these were on horseback. Their job was to protect the supply wagons and horses. About 8,500 horses were tied together to connect the main army to the wagons. This was to prevent the army from being surrounded.

Both sides wanted the other to attack first. So, from dawn until about 4:00 pm, the two armies stood facing each other under the hot sun. Bedford is said to have sent a messenger to Douglas. He asked what terms Douglas wanted for the battle. Douglas replied that the Scots would neither give nor ask for mercy.

The Milanese Attack

Around 4 pm, Bedford ordered his men to move forward. The English soldiers shouted "St. George! Bedford!" as they slowly walked across the field. A short archery fight happened between the English and Scottish archers. Neither side gained a clear advantage. At the same time, the 2,000 Milanese cavalry charged the English front line. They easily pushed aside the English wooden stakes. These stakes could not be firmly planted in the ground, which was hard from the summer sun. English arrows did not work well against the strong armor of the Italian soldiers.

The Milanese charge shocked the English. Soldiers and archers were knocked down. Gaps appeared in the English lines as they tried to avoid the charging horses. Some soldiers threw themselves to the ground and were ridden over. The Milanese rode through the entire English formation. They scattered the archers on the English right side.

Many English soldiers panicked during the Milanese charge. A Captain Young was later found guilty of being a coward. He retreated with his 500 men without orders, thinking the battle was lost. Young was severely punished for his retreat. English mounted troops fled to Conches. There, they told the small group of soldiers that the battle was lost. At Bernay, more Englishmen announced Bedford's defeat. At Pont-Audemer, news of an English disaster caused a rebellion. Retreating English troops had their armor and horses taken. Smaller uprisings also happened in the countryside.

The Milanese chased the fleeing English and attacked the English supply wagons. This caused an immediate retreat among the English. Some of the English soldiers at the back ran away. They fled on horseback or on foot. The Milanese continued to chase them or loot the supply wagons.

The Main Fight

After this powerful cavalry charge, Bedford gathered his soldiers. The English soldiers showed great discipline and reformed their lines. The French soldiers, sensing a victory, charged in a disorganized way. Narbonne's men reached the English before the rest of their comrades. The French were disorganized partly because they wanted to get close quickly to avoid English arrows. As the French advanced under Aumale, they shouted "Montjoie! Saint Denis!".

Bedford's soldiers advanced in good order towards the French. They paused often and shouted each time. The soldiers under Salisbury were heavily pressed by the Scots. A small group of French heavy cavalry on the right tried to go around the English line. But they were stopped by arrows from the English archers on the left. These 2,000 archers had moved and used the lines of tied horses for cover.

The direct clash between the well-armored English and French-Scottish soldiers at Verneuil was incredibly fierce. Both armies had marched on foot into battle. A writer named Desmond Seward said it was "a hand-to-hand combat whose ferocity astounded even contemporaries." Wavrin remembered how "the blood of the dead spread on the field and that of the wounded ran in great streams all over the earth." For about 45 minutes, French, Scottish, and English soldiers stabbed, hacked, and cut each other down. Neither side gained any advantage in what is often seen as one of the most intense battles of the entire war. Bedford himself fought in the battle. He used a powerful two-handed poleaxe. One veteran remembered: "He reached no one whom he did not fell." Seward noted that Bedford's poleaxe "smashed open an expensive armour like a modern tin can."

The English Main Attack

Many of the English archers on the right, who were scattered by the Milanese charge, had now regrouped. They, along with the archers on the left who had stopped the French cavalry, joined the battle. The archers joined the main fight with a loud shout. This greatly boosted the morale of the English soldiers. They then began a powerful attack on the French. After some time, the French battle line started to give way. It then broke and was chased back to Verneuil. Many French soldiers, including Aumale, fell into the moat and drowned. The ditches outside of town became a place where many fleeing French soldiers were killed without mercy. Narbonne and many other French nobles were killed.

After defeating the French, Bedford stopped the chase. He returned to the battlefield, where Salisbury was still fighting hard against the Scots, who were now alone. The battle ended when Bedford turned from the south to attack the Scots from their right side. Now almost surrounded, the Scots fought very bravely in a last stand. But they were overwhelmed. The English shouted "A Clarence! A Clarence!" This was to remember Thomas, Duke of Clarence, Bedford's brother, who had been killed at Baugé.

The English killed any Scotsmen in their way. Some surrendered but were still killed, to get revenge for Clarence's death. The long-standing hatred between Scotland and England meant no mercy was given. Almost the entire Scottish force died on the battlefield, including Douglas and Buchan. The Milanese cavalry returned to the battle at this point. They found their friends slaughtered. They then fled after losing 60 men. The English chased them until Bedford ordered a halt, allowing the Milanese to escape.

What Happened After

Dauphin Charles had to put off his plans to be crowned king at Reims. After Verneuil, it seemed possible for the English to take Bourges. This would have brought all of France under English rule. But Bedford, inspired by his late brother, Henry V, chose to focus on finishing the conquest of Maine and Anjou. He did not want to risk leading an advance into southern France with these two areas only partly conquered. Bedford preferred to conquer one area at a time carefully. He did not want to risk everything on one bold push to conquer southern France. Such a move might have brought all of France under English rule, but it could also have ended in disaster.

The results of the victory at Verneuil were: The English captured all border posts of Lancastrian Normandy. The only exception was Mont Saint-Michel, where the monks resisted. La Hire, who commanded another French force, pulled back to the east. Also, a French plan to take Rouen by digging tunnels was stopped, likely because of Bedford's victory.

Losses

Verneuil was one of the bloodiest battles of the Hundred Years' War. The English called it a second Agincourt. It was also a huge blow to French morale. For the second time in ten years, the proud French knights had met English archers in open battle and were completely defeated.

About 6,000–8,000 men on the French side were killed. In a letter written two days after the battle, Bedford said that 7,262 allied soldiers were killed. Bedford claimed his own losses were only two men-at-arms and "a very few archers." Wavrin, who saw the battle, estimated 6,000 killed on the French side, 200 captured, and 1,600 English deaths. Douglas fought on the losing side for the last time, dying with Buchan. Sir Alexander Buchanan, the man who had killed Clarence three years earlier, also died.

The Scottish army was badly hurt. It received far fewer new soldiers from Scotland for future fights against the English in France. This was not entirely unwelcome to the French. One French writer, Basin, wrote that the disaster at Verneuil was at least balanced by seeing the end of the Scots, "whose rudeness was unbearable." Among the prisoners were the Duke of Alençon and Marshal Gilbert Motier de La Fayette.

Charles VII was very sad about the disaster at Verneuil. But he continued to honor the survivors. One of them, John Carmichael of Douglasdale, who was the chaplain of the dead Douglas, became the Bishop of Orléans (1426–1438).

Bedford returned in triumph to Paris. There, "he was received as if he had been God... in short, more honor was never done at a Roman triumph than was done that day to him and his wife."

Learning About the Battle

French writings from that time give many details about how the people of Paris, who were under Burgundian rule, reacted. The Journal d'un bourgeois de Paris and Enguerrand de Monstrelet's writings are important sources for this battle. The Chronique de Charles VII, roi de France, written by the king's historian Jean Chartier (around 1390–1464), confirmed that the English won completely. French writers mourned the many lives lost for Charles VII's cause.

Richard Ager Newhall's study of warfare from 1924 is still a trusted source for the battle's tactics and events. The Victorian Rev. Stevenson translated a French study about the noble families who suffered greatly in the Hundred Years' War. This is often quoted. Also, Siméon Luce (1833–1892), a 19th-century French historian, copied information from original documents that are still in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. These later sources are all we have, as many of the original accounts from that time are lost. The English later had the advantage of the Burgundian Jean de Wavrin traveling with their army, but he wrote little about Verneuil.

Images for kids

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |