Dryburgh Abbey facts for kids

|

|

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Premonstratensian |

| Established | 1150 |

| Disestablished | bet. 1581 and 1600 |

| Mother house | Alnwick Abbey |

| Diocese | Diocese of St. Andrews |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Hugh de Morville |

| Important associated figures | Adam of Dryburgh, Andrew Forman |

Dryburgh Abbey is an old abbey near Dryburgh in the Scottish Borders. It sits by the River Tweed. It was started on November 10, 1150. This happened when Hugh de Morville, Constable of Scotland, made a deal with the Premonstratensian canons (a type of monk) from Alnwick Abbey in England. The first monks and their leader, Abbot Roger, arrived on December 13, 1152.

English soldiers burned the abbey in 1322. It was rebuilt, but then burned again by King Richard II in 1385. Even so, it became very successful in the 1400s. The abbey was finally destroyed in 1544. It lasted a short time after that, until the Scottish Reformation (a big change in religion). Then, King James VI of Scotland gave it to the Earl of Mar. Today, it is a protected historic site. The land around it is also a special designed landscape.

David Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan bought the land in 1786. Famous people like Sir Walter Scott and Douglas Haig are buried there. Their graves and other memorials are important historical buildings.

Contents

- The Premonstratensian Order

- How Dryburgh Abbey Was Supported

- New Monasteries Started by Dryburgh

- Abbey's Money Troubles

- Changes in Support

- Wars for Scottish Independence

- The Border Lands Divided

- A Turning Point for the Abbey

- The Last Century of the Abbey

- Daily Life of the Monks

- Fat Lips

- Visiting the Abbey

- Images for kids

- See also

The Premonstratensian Order

The Premonstratensian order was started by St Norbert of Xanten. He was a church leader at Xanten Cathedral. Norbert was not happy with how other church leaders lived. So, he left his home area and went to Laon, in northern France. There, Bishop Bartholomew was trying to make his church more like the early Christian church.

Bishop Bartholomew convinced Norbert to create a new order of monks at Prémontré in 1120. These monks followed the rules of Saint Augustine. But they wore white robes instead of black. They lived a very strict life. They also had a duty to preach and teach people outside the monastery walls. This order quickly spread across Europe. The leader of Prémontré became the main leader for all the other monasteries. Even before the first main leader died, 120 abbots (monastery leaders) came to their yearly meeting. The Premonstratensians also used ideas from another group, the Cistercians. This included how they managed land and used lay-brothers (non-monks) to do the hard work.

How Dryburgh Abbey Was Supported

Dryburgh Abbey did not have a king supporting it, unlike Melrose Abbey nearby. But Hugh de Morville, who started Dryburgh, was very rich. King David I of Scotland also helped the abbey. He allowed them to take wood from his forests to build the abbey. Hugh de Morville gave the abbey land, forests, and water at Dryburgh. He also gave them fishing rights from Berwick. He gave them churches and land in Mertoun and Channelkirk. These were in his area of Lauderdale. He also gave them land in Asby in Westmoreland, and money from mills in Saltoun and Lauder. Hugh's wife, Beatrice de Beauchamp, gave money from a church in Bozeat, England. She also bought land in Roxburgh just to give to the abbey.

Around 1162, Hugh de Morville decided to become a monk at Dryburgh Abbey. He gave his older son, Richard, his Scottish lands. His younger son, Hugh, got the lands in England. Hugh de Morville (the father) died at Dryburgh Abbey that same year.

After Hugh's death, his son Richard continued to support the abbey. But around 1170, he started a hospital near his castle. Then, between 1169 and 1187, he started Kilwinning Abbey. Kilwinning Abbey was built very grandly. But it did not have enough money to run it. So, Richard made sure some of its costs came from his lands in Lauderdale. This caused arguments between Kilwinning and Dryburgh. Both abbeys ended up being quite poor because of this.

New Monasteries Started by Dryburgh

Even with not enough money, Dryburgh Abbey had many new monks join. By the late 1100s, the abbey was too crowded. So, they had to start new monasteries. John de Courcy, a powerful lord in Ulster (Ireland), started one at Carrickfergus. He also started another at Drumcross. But these new monasteries did not do well for long. This was mostly because of the many political problems in Ulster during the 1200s. It was not because of problems at Dryburgh.

Abbey's Money Troubles

At the start of the 1200s, Dryburgh Abbey began to rebuild. They wanted to make it bigger and grander. But building with stone was expensive. And the abbey did not have a steady income. So, the building work took a very long time. Also, the abbey got into many legal fights about land and money. In April 1221, a special church official had to come to Dryburgh to settle these problems.

The building work continued into the 1240s. The abbey's debts grew very large. So, in 1242, the Bishop of St Andrews allowed the abbot to let his monks work in other churches. This was to help pay off the "grinding debts" from building and other needs.

In 1246, Pope Innocent IV gave the abbey a special gift. For 40 days each year, visitors to the abbey could get a special blessing. This was meant to encourage people to visit and give money. The Pope also protected the abbey from having to pay out money for pensions. He also protected the monastery and its monks from legal problems.

Abbot John was blamed for not managing money well. He had to resign. In 1255, Pope Alexander IV ordered that most of the abbey's money should go to paying off debts. Only a small amount was kept for daily needs. Over the next 40 years, the abbey's money situation slowly got better. But it was still not as rich as other nearby monasteries. Those abbeys had much more land for grazing animals, which brought in more money.

Changes in Support

The family of Hugh de Morville, who founded the abbey, ended in 1196. His grandson, William, died. The lands then went to William's sister, Helen. Her husband was Lochlann, Lord of Galloway. The Lords of Galloway were much richer than the de Morvilles. But they supported many religious houses. So, they could not give huge amounts of money to Dryburgh.

Dryburgh was one of many places asking the Galloway lords for money. But in 1234, Alan, the last of the Galloway lords, died. His property was split among his three daughters and their husbands. The lands that used to belong to the de Morvilles were divided again. By the 1250s, these lands were held by Helen of Galloway and her husband, Roger de Quincy. They were also held by Dervorguilla of Galloway and her husband, John I de Balliol. These new owners had their own places to support. So, they gave less to Dryburgh. However, the de Quincys did give some fishing rights and land near Bemerside. Dervorguilla mostly cared about her own abbey, Sweetheart Abbey. But she was at Dryburgh in 1281 to give her English lands to her son, John Balliol. He would become king.

John Balliol became King of Scotland in 1292. But his rule was short. He gave up the throne in 1296 after Scotland lost battles to King Edward I of England. This ended a long time of peace in the border areas.

Wars for Scottish Independence

The leaders of Dryburgh, Jedburgh, Melrose, and Kelso abbeys all agreed to obey King Edward I of England in 1296. So, Edward ordered that Dryburgh Abbey's lands be returned to it. For many years after this, there are few records of the abbey. But we know that a high-ranking English officer, Sir Henry de Percy, stayed at Dryburgh in 1310.

The abbey was linked to the Balliol family, who were against the Scottish King Robert the Bruce. But before 1316, the abbot and monks of Dryburgh kicked out two of their own. These two refused to accept Robert as their king. King Edward II of England was pleased. He rewarded them by giving them back the rent and fishing rights from the abbey at Berwick.

We don't know much about Robert the Bruce helping Dryburgh. He did use the abbey as a base in 1316 when he raided northern England. In 1322, King Edward II of England attacked Scotland in return. His army burned Melrose and Dryburgh abbeys. Robert the Bruce gave a lot of money to rebuild Melrose. But Dryburgh seemed to be ignored. It's unclear why Bruce was not as generous to Dryburgh. Melrose got £2000, while Dryburgh only got a small yearly payment that was already in place.

However, Walter Stewart, 6th High Steward of Scotland, who was Bruce's son-in-law, did help the abbey. He gave them rights from a church and some of his own land. In 1326, the Bishop of Glasgow allowed the monks to use the church's money to help rebuild. Bruce's brother-in-law, Sir Andrew Murray, also may have given land. Other less important people also gave gifts. These included land and other possessions.

Robert the Bruce died in 1329. In 1332, Edward Balliol, King John's son, returned to Scotland with an army. He defeated the Scottish army and became king. But he was soon forced to flee to England. With help from King Edward III of England, Balliol became king again. But he had to give up some Scottish lands to Edward. Dryburgh was once again under English control. This did not seem to hurt the abbey. An English sheriff even bought and gave the abbey a large property in Roxburgh.

In 1334, Balliol had to seek protection in Berwick. The English were losing control in Scotland. In 1335, Edward III marched his army to Scotland. He expected the Scots to surrender at Dryburgh Abbey, but they did not. David II returned from France in 1342. More lands were won back by the Scots. By 1346, the area around Roxburgh was back under Scottish control. Scottish lords again supported the monks. But David II was captured in 1346 at the Battle of Neville's Cross. An English army took control of Roxburgh. So, the central border lands were back under English control for over 20 years.

In 1356, the abbot of Dryburgh and other abbots witnessed Edward Balliol giving up his claim to the Scottish throne. After England won a battle against France, Scotland lost its ally. This forced Scotland to negotiate for David II's release. David was released in 1357. But Scotland had to pay a huge ransom. England also kept control of the occupied lands until the ransom was paid.

The Border Lands Divided

When David II was freed in 1357, England kept control of the southeastern parts of Scotland. This meant Dryburgh and other border abbeys stayed in English-held areas. David allowed the abbeys to keep their Scottish lands. He did not stop the monks from getting money from those lands. Dryburgh's records from this time were lost. So, we know about its situation mostly from records of Melrose Abbey.

Exporting wool was important to King David. So, he encouraged border abbeys, which produced a lot of wool, to use Scottish ports. This was instead of English ports like Berwick. In the 1360s and 1370s, England's control over the border areas weakened. They only held onto castles like Berwick and Roxburgh. In 1384 and 1385, Scottish raids into England increased. This made King Richard II of England lead his army into Scotland. He burned Edinburgh and ordered the destruction of Dryburgh, Melrose, and Newbattle abbeys.

A Turning Point for the Abbey

The damage to Dryburgh was very bad. Important nobles helped a lot to rebuild it. In the late 1380s, Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany, Archibald Douglas, and Bishop Walter Trail all helped the abbey recover. In 1391, King Robert III gave the monks all the rich lands of the Cistercian nuns of South Berwick. These lands had been destroyed by Richard II in 1385.

The Black Douglas family continued to support the abbey. Around 1420, Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas gave Dryburgh money from the church lands of Smailholme. The fifth earl continued this gift. In 1429, he asked the Pope to officially confirm it. He also included the hospitals of St Leonards of Lauder and Smailholme. In 1443, the abbey was damaged by fire again, likely by accident. But 18 years later, in 1461, the abbey asked Pope Pius II for protection. This suggests the monks were struggling to pay for repairs.

The Last Century of the Abbey

The abbey lost the support of Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany when he died in 1420. In 1455, the Black Douglas family lost their lands. This meant the abbey lost a major helper and protector in James Douglas, 9th Earl of Douglas. Walter Dewer was chosen as abbot in 1461. He was likely the last abbot chosen by the monks themselves. But under his leadership, the abbey started to lose its lands. The rest of the 1400s saw many fights over who would be abbot. There were also expulsions, refusals from the Pope, or kings getting involved.

Commendators

King James IV rewarded church leaders who served him well. He gave them "commendatorships." This meant they would manage an abbey and receive its income, even if they weren't monks. The first commendator of Dryburgh Abbey was Andrew Forman, a bishop, in 1509. Forman was mainly a diplomat for King James IV. He traveled a lot in Europe. He became very rich from his church and other jobs.

Forman gave up his rights to Dryburgh after he became Archbishop of St Andrews. James Ogilvie, another church leader and diplomat, took over in 1516. He was commendator for only a short time, dying in 1518.

David Hamilton, a bishop and brother of a powerful lord, was the next to be suggested for the abbey. He became commendator in 1519 and died in 1523.

The next person to lead the abbey was James Stewart, a church leader from Glasgow. He got the abbey's income in 1526 and held it until his death in 1539.

In 1539, King James V suggested Thomas Erskine as the next commendator. He was confirmed in 1541. In 1541, fighting started again between Scotland and England. But Dryburgh was safe until November 7, 1544. That's when Edward Seymour, an English earl, burned the town of Dryburgh and its abbey. He came back in 1545 and burned the abbey again.

Erskine was captured by the English. He was ransomed for £500. Dryburgh would have had to help pay this large sum. Perhaps because of this, in 1548, he gave his commendatorship to his brother John.

Like most commendators before him, John Erskine was not very interested in the religious side of the abbey. He was an important person in Scottish politics. John was commendator until 1556. Then he stepped down for his nephew, David Erskine.

David Erskine became commendator in 1556. He quickly started giving away the abbey's lands to important local families. Erskine was involved in kidnapping King James VI. When the king escaped, Erskine and his friends fled to England. Erskine lost his lands, and the commendatorship of Dryburgh Abbey was given to William Stewart.

William Stewart was commendator for just over a year. In 1585, David Erskine gained favor with King James VI again. He got all his lands and titles back.

In June 1600, Erskine wrote that all the monks had died. This marked the end of the monastery. In 1604, the remaining lands of the abbey became part of the Lordship of Cardross. This belonged to John Erskine, who was then the Earl of Mar. Henry Erskine, Mar's son, received the title of commendator of Dryburgh Abbey.

Daily Life of the Monks

The monks' daily life included religious services, farm work, household duties, copying books, and reading. Here's what a typical day might have looked like:

- The first service, Matins, was held very early in the morning. A bell woke the monks. They went to the church for this service, then returned to bed.

- The Prime service was at 6 a.m. The monks woke up again and went to church for mass. They prayed privately until a bell called them to a daily meeting.

- The community met in the chapter house. A lesson from the order's rules was read. Anyone who had broken rules was held accountable. Punishments were given by the prior (a leader among the monks).

- In winter, at 9 a.m. (called Tierce), after the meeting, the monks went to church to sing hymns. In summer, there was more time before Tierce for abbey duties. The summer Tierce was a main mass.

- The main mass in winter was at midday (called Sext).

- The community ate at 1 p.m. They were usually served only two dishes. Sometimes, they got an extra sweet dish. If someone was late for the meal without a good reason, they had to sit at a far table and might not get wine or ale.

- After dinner, some monks rested, while others talked. At 3 p.m. (called Nones), they went to church for another service. After that, they washed their hands and waited to be called to drink.

- At 6 p.m., the monks attended Vespers.

- Compline, the last service of the day, was held after 7 p.m. This was followed by a light supper and then bed.

- The monks slept in their robes. Their beds in the dormitory did not have sheets.

- In autumn, the monks who worked on the farm left early in the morning. Sometimes, they did not return until after the evening service. They still had to say their prayers at the right times while they worked.

Fat Lips

There is a local story about a friendly spirit called Fat Lips living in the ruins of Dryburgh Abbey. A woman who lost her loved one in the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion lived in the ruined abbey. She said that Fat Lips, a small man in iron boots, used to tidy her room for her.

Visiting the Abbey

Dryburgh Abbey is one of several abbeys and historic sites in Scotland. You can visit it as part of the Borders Abbeys Way walking trail.

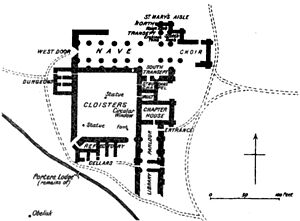

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Abadía de Dryburgh para niños

In Spanish: Abadía de Dryburgh para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |