Geography (Ptolemy) facts for kids

The Geography (also known as Geographia or Cosmographia) is a super important book from ancient times. It was written by a smart Greek scholar named Claudius Ptolemy around 150 AD in Alexandria, Egypt. This book was like a giant map collection, a list of places, and a guide on how to make maps. It brought together all the geographical knowledge from the Roman Empire at that time.

Ptolemy's work was a new version of an older map book by Marinus of Tyre, but Ptolemy added more information from Roman and Persian records. He also came up with new ideas for making maps. Later, in the 800s, the book was translated into Arabic. This translation had a huge impact on how people in the Islamic world understood geography and made maps. Along with the work of Islamic scholars, Ptolemy's Geography also greatly influenced mapmaking and geographical knowledge in Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Contents

Old Copies of the Geography

Ptolemy's original book probably came with actual maps. However, some experts think that the parts of the text that talk about maps might have been added later by other people.

We don't have any copies of the Geography in Greek that are older than the 1200s. A Byzantine monk named Maximus Planudes wrote that he looked for a copy in 1295. One of the oldest copies we have today might be one that he put together. In Europe, people sometimes redrew maps using the location details from the book, just like Planudes had to do. Later, people who copied books would then copy these new maps.

The first Latin translation of these texts was made in 1406 or 1407 by Jacobus Angelus in Florence, Italy. It was called Geographia Claudii Ptolemaei. It's believed that his version didn't have maps, even though a Greek copy with maps had been brought to Florence earlier.

What's Inside the Geography?

Ptolemy's Geography is split into three main parts, spread across eight books.

How to Make Maps

Book 1 is like a textbook on cartography (mapmaking). It explains the methods Ptolemy used to gather and organize his information. Maps based on scientific principles had been made in Europe since the 3rd century BC. Ptolemy made improvements to how maps were projected onto a flat surface. He gave clear instructions on how to create his maps in this first section.

A List of Places

Books 2 through the beginning of Book 7 are a huge list of places. This list gives the latitude and longitude coordinates for all the places and features in the "ecumene" – which was the world known to the ancient Romans. Latitude was measured in degrees from the equator, just like today. Ptolemy used fractions of a degree instead of minutes. His starting line for longitude (0 degrees) went through the Fortunate Isles, which are now thought to be near El Hierro in the Canary Islands. His maps covered 180 degrees of longitude, from the Fortunate Isles in the Atlantic all the way to China.

Ptolemy knew that Europeans only knew about a quarter of the entire Earth.

Maps of the World

The rest of Book 7 explains three different ways to draw a map of the world. These methods varied in how complex they were and how accurate they would be. Book 8 was an atlas of regional maps. These maps included some of the location details from earlier in the book. These details were meant to be used as captions to make the maps clear and keep them accurate when copied.

Ptolemy's work included one large, less detailed world map, and then many separate, more detailed regional maps. The first Greek copies found after Maximus Planudes rediscovered the text had as many as 64 regional maps. In Western Europe, the standard set became 26 maps: 10 for Europe, 4 for Africa, and 12 for Asia. By the 1420s, new maps were added to this collection, showing places like Scandinavia.

History of the Geography

Ancient Times

The original map book by Marinus of Tyre that Ptolemy used is now completely lost. A world map based on Ptolemy's work was even displayed in a Roman city in France during late Roman times. Later Roman writers and mathematicians mostly just wrote comments about Ptolemy's text instead of trying to make it better. In fact, later records show that their maps became less accurate. However, scholars in the Byzantine Empire kept these geographical traditions alive throughout the Middle Ages.

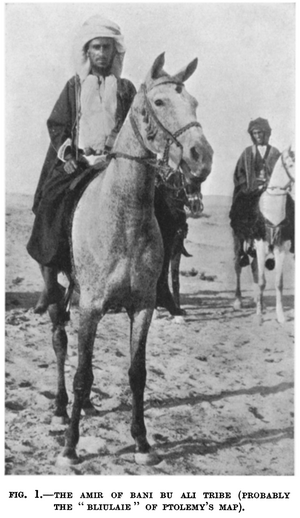

Earlier Greek and Roman geographers like Strabo and Pliny the Elder didn't really trust the stories of sailors and merchants who traveled to far-off places like the Indian Ocean. But Marinus and Ptolemy were much more open to using information from them. For example, some historians believe they couldn't have drawn the Bay of Bengal so accurately without the help of sailors' accounts. For places like the Malay Peninsula and the South China Sea, Marinus and Ptolemy used information from a Greek sailor named Alexandros. He claimed to have visited a far eastern place called "Cattigara" (which was likely Oc Eo, Vietnam, where Roman goods have been found).

Medieval Islam

Muslim mapmakers were using copies of Ptolemy's Geography by the 800s. Around that time, a scholar named al-Khwārazmī created his Book of the Depiction of the Earth. This book was similar to Ptolemy's Geography, giving coordinates for 545 cities and regional maps of places like the Nile. The oldest surviving maps from Islamic lands are from a 1037 copy of al-Khwārazmī's work. His book clearly states he used an earlier map, but it wasn't an exact copy of Ptolemy's. For example, his starting line for longitude was different, and he added some new places.

Even though Muslim scholars started collecting many lists of places and coordinates based on Ptolemy's work, they didn't often use Ptolemy's exact mapmaking rules in the maps that have survived. Instead, they followed al-Khwārazmī's changes and other methods. Most surviving maps from this period were not made using strict mathematical rules.

Ptolemy's Geography was translated from Arabic into Latin in the 1100s in Sicily, but no copies of that translation have survived.

The Renaissance

The Greek text of the Geography arrived in Florence, Italy, around 1400. It was then translated into Latin by Jacobus Angelus around 1406. The first printed version with maps came out in 1477 in Bologna. This was also the first printed book to have engraved pictures. Many more editions followed, some using the traditional maps and others updating them.

Ptolemy's maps showed the world from the Cape Verde or Canary Islands in the west all the way to the eastern shore of the Magnus Sinus (Great Gulf). This known part of the world covered 180 degrees of longitude. In his far east, Ptolemy placed Serica (the Land of Silk) and the port of Cattigara. On maps based on Ptolemy's work, like the 1489 world map by Henricus Martellus, Asia ended in a cape called the Cape of Cattigara. Ptolemy thought Cattigara was a port on the Gulf of Thailand, at about eight and a half degrees north of the Equator. This was the easternmost port reached by ships trading from the Greek-Roman world to the Far East.

However, in a later, more famous version of Ptolemy's Geography, a mistake was made when copying. Cattigara was placed at eight and a half degrees south of the Equator. This mistake meant that the coast of China, which should have been shown as part of eastern Asia, was wrongly shown as an eastern shore of the Indian Ocean. Because of this, Ptolemy's map suggested there was more land east of the 180th meridian and an ocean beyond it.

Marco Polo's stories about his travels in eastern Asia described lands and seaports on an eastern ocean that Ptolemy didn't know about. Marco Polo's accounts allowed for many additions to Ptolemy's map, as seen on Martin Behaim's 1492 globe. Since Ptolemy didn't show an eastern coast of Asia, Behaim could extend that continent much further east. Behaim's globe placed Marco Polo's Mangi and Cathay east of Ptolemy's 180th meridian.

How it Influenced Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus changed this geography even more. He used a shorter measurement for a degree of longitude than Ptolemy did. He also used Marinus of Tyre's longitude of 225 degrees for the east coast of the Magnus Sinus. This made the longitudes much further east than what Martin Behaim and others of Columbus's time believed.

Columbus thought that the longitudes of eastern Asia and Japan were around 270 and 300 degrees east, or 90 and 60 degrees west of the Canary Islands. He said he had sailed 1100 leagues from the Canaries when he found Cuba in 1492. This was roughly where he expected to find the coast of eastern Asia. Based on this, he thought Hispaniola was Japan. His later trips led to more exploration of Cuba and the discovery of South and Central America.

Errors in Longitude and Earth Size

Ptolemy's maps had a couple of related errors:

- He often overestimated the longitude of places. This means that places on his maps were stretched out horizontally, especially noticeable in the shape of Italy.

- Ptolemy believed the known world covered 180 degrees of longitude. But instead of using Eratosthenes's estimate for the Earth's circumference (which was more accurate), he made it smaller. This suggests Ptolemy adjusted his longitude data to fit his smaller idea of the Earth's size. Ptolemy often adjusted experimental data in his other works too.

Images for kids

-

1st Map of Europe

The islands of Albion (Great Britain) and Hibernia (Ireland). -

2nd Map of Europe

Hispania Tarraconensis, Baetica, and Lusitania (parts of ancient Spain and Portugal). -

7th Map of Europe

The islands of Sardinia and Sicily. -

9th Map of Europe

Dacia, Moesia, and Thrace (parts of modern Romania, Bulgaria, Greece). -

10th Map of Europe

Macedonia, Achaea, the Peloponnesus, and Crete (parts of modern Greece). -

2nd Map of Africa

Africa (part of modern Tunisia). -

3rd Map of Africa

Cyrenaica, Marmarica, Libya, Lower Egypt, and the Thebaid (parts of modern Libya and Egypt). -

4th Map of Africa

North, West, East, and Central Africa. -

3rd Map of Asia

Colchis, Iberia, Albania, and Greater Armenia (parts of the Caucasus region). -

4th Map of Asia

Cyprus, Syria, Palestine/Judea, Arabia Petrea and Deserta, Mesopotamia, and Babylonia (parts of the Middle East). -

5th Map of Asia

Assyria, Susiana, Media, Persia, Hyrcania, Parthia, and Carmania Deserta (parts of ancient Persia/Iran). -

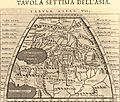

7th Map of Asia

Scythia within Imaus, Sogdiana, Bactriana, Margiana, and the Sacae (parts of Central Asia). -

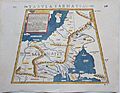

8th Map of Asia

Scythia beyond Imaus and Serica (parts of Central Asia and China). -

11th Map of Asia

India beyond the Ganges, the Golden Chersonese (Malay Peninsula), the Magnus Sinus (South China Sea), and the Sinae (China).

See also