Warfare in Medieval Scotland facts for kids

Warfare in Medieval Scotland is all about the fighting and military actions that happened in what we now call Scotland, or by Scottish forces, from when the Romans left in the 400s until the early 1500s. During this long time, conflicts grew from small raids to huge battles, and Scotland adopted many new ideas from other parts of Europe.

In the Early Middle Ages, land battles often involved small groups of warriors, like a leader's personal guards, who mostly did raids and small fights. When the Vikings arrived, they brought a new level of naval warfare. They moved quickly using their special longships. Later, the birlinn, a ship similar to the longship, became very important for fighting in the Highlands and Islands.

By the High Middle Ages, the kings of Scotland could gather armies of tens of thousands of men for short times. These were called the "common army" and were mostly spearmen and archers with light armor. After the "Davidian Revolution" in the 1100s, which brought parts of feudalism to Scotland, these armies were joined by a few mounted and heavily armored knights. Feudalism also brought castles to Scotland. At first, these were simple wooden motte-and-bailey castles. But in the 1200s, they were replaced by stronger stone "enceinte" castles with tall walls. In the 1200s, the threat from Viking ships became smaller, and Scottish kings could use their own ships to help control the Highlands and Islands.

Scottish armies on the battlefield usually struggled against the larger and more professional English armies. However, Robert I of Scotland used them very well at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 to win Scottish independence. He decided to destroy castles so the English couldn't use them easily. He also started to build a royal Scottish navy. In the Late Middle Ages, under the Stewart kings, armies got even stronger with special troops like men-at-arms and archers. These soldiers were hired using agreements called manrent. New "livery and maintenance" castles were built to house these troops, and castles started to change to use gunpowder weapons. The Stewarts also adopted big changes from European warfare, like longer pikes and lots of artillery. They also built a strong navy. But even one of the biggest and best-armed Scottish armies ever still lost to an English army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. Many ordinary soldiers, a large part of the Scottish nobles, and King James IV himself died in that battle.

Contents

Early Medieval Battles

Brave Warriors

In early medieval Scotland, which was divided into many small kingdoms, the main part of any army was a leader's personal guards or war-band. These groups were small, probably no more than 120-150 men. They were very loyal to their leader.

In times of peace, these war-bands gathered in a "Great Hall." Here, they would feast, drink, and bond, which kept the group strong. The war-band was the core of larger armies that were sometimes gathered for big campaigns. These bigger forces were formed because people had a duty to defend their land or kingdom. Early records from Dál Riata (a kingdom in western Scotland) show that this duty was linked to how much land someone owned. People had to provide a certain number of men or ships based on their land.

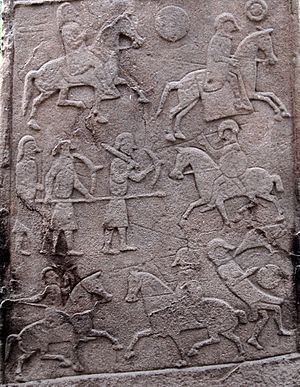

Pictures on Pictish stones, like the one at Aberlemno, show warriors with swords, spears, bows, helmets, and shields. These images might show foot soldiers fighting together or mounted warriors, sometimes with heavy armor, suggesting there was a group of elite horsemen.

Strong Hill Forts

Early forts in Scotland, especially in the north and west, included small stone towers called brochs and duns. In the south and east, there were larger hill forts. We know of about 1,000 Iron Age hillforts in Scotland, mostly south of the Clyde-Forth line. They seemed to have been left empty during the Roman period but were used again after the Romans left. Most are round, with a single wooden fence around an enclosed area.

Forts in the Early Medieval period were often smaller and more compact. They sometimes used natural features, like at Dunadd and Dunbarton. Because there were so many hill forts in Scotland, big open battles might have been less common than in Anglo-Saxon England. Many kings are recorded as dying in fires, which suggests that sieges (surrounding and attacking a fort) were a more important part of warfare in northern Britain.

Ships and Sea Power

Control of the sea was also very important. Irish records mention a Pictish attack on Orkney in 682, which would have needed a large navy. They also lost 150 ships in a disaster in 729. Ships were also key for fighting in the Highlands and Islands. From the 600s, a record called the Senchus fer n-Alban shows that Dál Riata had a system where groups of households had to provide 177 ships and 2,478 men. This record also mentions the first recorded naval battle around the British Isles in 719 and eight naval trips between 568 and 733.

The only ships that survive from this time are dugout canoes. But pictures from the period suggest there might have been skin boats (like the Irish currach) and larger boats with oars. The Viking raids and invasions of Britain were successful because they had better ships. Their long-ships were fast, light, wooden boats with a shallow bottom. This shallow bottom meant they could sail in water only about 1 meter deep and land easily on beaches. They were also light enough to be carried over land. Longships had the same shape at both ends, so they could quickly change direction without turning around.

High Medieval Battles

Land Armies

By the 1100s, the way to gather large numbers of men for big campaigns became more organized. It was called the "common army" (communis exercitus) or "Scottish army" (exercitus Scoticanus). Everyone who owned land had a duty to join. This system could create a regional army, like when Robert I (before he was king) raised "my army of Carrick" from 1298 to 1302. It could also create a national Scottish army, as he did later during the Wars of Independence.

Later rules said that the common army was made up of all healthy free men aged 16 to 60, with 8 days' warning. This produced many men who served for a short time, usually as archers and spearmen with little or no armor. In this period, the common army continued to be gathered by the earls, who often led their men in battle, like at the Battle of the Standard in 1138. This army continued to be the main part of Scottish national armies, potentially bringing tens of thousands of men for short fights, even into the early modern period.

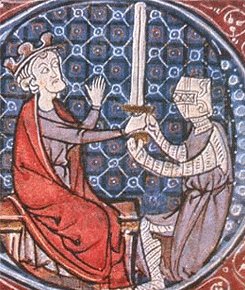

Smaller numbers of feudal troops also developed. The idea of feudalism came to Scotland mainly during the "Davidian Revolution" in the 1100s. When David I became king in 1124, he had lived much of his life as a baron in England. He brought many Anglo-Norman nobles with him, giving them land and titles. This brought "major changes in military organization," including the knight's fee (land given in exchange for military service) and the regular use of professional cavalry (knights). Knights held castles and land in return for serving for 40 days, providing troops. David's Norman followers could provide about 200 mounted and armored knights. But most of his forces were the "common army" of lightly armed foot soldiers. These foot soldiers were good at raiding and guerrilla warfare. They only sometimes managed to defeat the English in open battle, but they did so crucially at Stirling Bridge in 1297 and Bannockburn in 1314 during the Wars of Independence.

Castles and Forts

Castles, which were fortified homes for lords or nobles, arrived in Scotland when David I encouraged Norman and French nobles to settle there. They were especially common in the south and east and helped control the lowlands. At first, these were mostly wooden motte-and-bailey castles. These had a raised mound (motte) with a wooden tower on top, and a larger enclosed area (bailey) next to it. Both were usually surrounded by a ditch and a wooden fence, connected by a wooden bridge. They varied in size, from very large ones like the Bass of Inverurie to smaller ones like Balmaclellan.

In England, many of these wooden castles were rebuilt in stone as "keep-and-bailey" castles in the 1100s. But in Scotland, most castles that stayed in use became stone "enceinte" castles. These had a tall, strong outer wall with battlements. Besides the castles built by nobles, there were also royal castles. These were often larger and provided defense, a place for the king's court to stay, and a local government center. By 1200, these included forts at Ayr and Berwick.

During the wars of Scottish Independence, Robert I decided to destroy castles rather than let the English easily capture or recapture them and use them against him. He started with his own castles at Ayr and Dumfries, and also destroyed Roxburgh and Edinburgh.

Ships and Sea Battles

In the Highlands and Islands, the longship slowly changed into the birlinn, highland galley, and lymphad (listed from smallest to largest). These were ships built with overlapping planks, usually with a mast in the middle, but they also had oars. Like the longship, they had high front and back ends. They were still small and light enough to be pulled over land. From the late 1100s, they started using a rudder at the back instead of a steering board. They could fight at sea, but they rarely matched the armed ships of the Scottish or English navies. However, they could usually outrun bigger ships and were very useful for quick raids and escaping.

Ships for war were gathered through a system where land owners had to provide them. This system might go back to the Dál Riata ship-muster system, but it was probably brought in by Scandinavian settlers. Later, providing ships for war became linked to feudal duties. Celtic-Scandinavian lords, who used to provide ships based on a general land tax, now held their lands in exchange for a specific number and size of ships for the king. This likely started in the 1200s and became even more important under Robert I. The importance of these ships is shown by how often they appear on grave markers and in family symbols (heraldry) throughout the Highlands and Islands.

Medieval records mention fleets (groups of ships) led by Scottish kings like William the Lion and Alexander II. Alexander II personally led a large group of ships from the Firth of Clyde in 1249. They stopped near the island of Kerrera, planning to carry his army to fight the Kingdom of the Isles, but he died before the campaign could start.

Viking sea power was weakened by fights between the Scandinavian kingdoms. But it became strong again in the 1200s when Norwegian kings started building some of the biggest ships seen in Northern Europe. These included King Hakon Hakonsson's Kristsúðin, built in Bergen from 1262–63. It was about 79 meters long and had 37 rooms. In 1263, Hakon responded to Alexander III's plans for the Hebrides by personally leading a large fleet of 40 ships, including the Kristsúðin, to the islands. There, local allies joined them, making the fleet as large as 200 ships. Records show that Alexander had several large oared ships built at Ayr, but he avoided a sea battle. A defeat on land at the Battle of Largs and winter storms forced the Norwegian fleet to go home. This left the Scottish crown as the main power in the region, leading to the Western Isles being given to Alexander in 1266.

Late Medieval Battles

Changing Armies

Scottish wins in the late 1200s and early 1300s are seen as part of a bigger "infantry revolution." This was when mounted knights became less important on the battlefield. However, Scottish medieval armies had probably always relied on foot soldiers. In the late medieval period, Scottish men-at-arms (professional soldiers) often got off their horses to fight alongside the foot soldiers, keeping only a small group of mounted reserves. Some think the English copied and improved these tactics, which helped them win battles in the Hundred Years' War. Like the English, the Scots used mounted archers and even spearmen, who were very useful in the fast raids common in border warfare. But like the English, they fought on foot in big battles.

By the second half of the 1300s, besides soldiers gathered by common duty and feudal agreements, money contracts called bonds or bands of manrent were used to hire more professional troops, especially men-at-arms and archers. In reality, different ways of serving often mixed together. Many major Scottish lords brought groups of their relatives to fight. These systems produced many lightly armored foot soldiers, usually armed with spears about 3.6 to 4.2 meters long. They often formed large, tight defensive groups called shiltrons. These formations could stop mounted knights, as they did at Bannockburn, or stop foot soldier attacks, as at Otterburn in 1388. But they were weak against arrows (and later, artillery fire) and couldn't move very fast, as shown at Halidon Hill in 1333 and Humbleton Hill in 1402.

There were attempts to replace spears with longer pikes (4.7 to 5.6 meters) in the late 1400s. This was to copy the success of armies in the Netherlands and Switzerland against mounted troops. But this didn't seem to work well until just before the Flodden campaign in the early 1500s. There were fewer archers and men-at-arms, and they were often outnumbered when fighting the English. Scottish archers mostly came from the border regions, with those from Selkirk Forest having a very good reputation. They were highly sought after as hired soldiers in French armies in the 1400s, to help fight against the English's strong archers. They became a major part of the French royal guards as the Garde Écossaise.

Castle Defenses

After the Wars of Independence, new castles began to be built. These were often larger "livery and maintenance" castles, designed to house hired troops. Examples include Tantallon in Lothian and Doune near Stirling, which was rebuilt for Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany in the 1300s.

Most of the Late Medieval forts built by nobles in Scotland, about 800 of them, were tower houses. Smaller versions of tower houses in southern Scotland were called peel towers. Tower houses were mainly designed to protect against small raiding parties. They were not meant to stand up to a large, organized army attack. Historian Stuart Reid described them as "defensible rather than defensive." They were usually tall, square, stone buildings with crenellations (notches on the top of walls). Often, they were also surrounded by a barmkyn or bawn, which was a walled yard for keeping valuable animals safe, but not necessarily for serious defense. They were built a lot on both sides of the border with England. When James IV took control of the Lordship of the Isles in 1494, it led to a sudden burst of castle building across that region.

Gunpowder weapons completely changed how castles were built. Existing castles were changed to use gunpowder weapons by adding "keyhole" gun ports, platforms for guns, and stronger walls to resist cannon fire. Ravenscraig in Kirkcaldy, started around 1460, is probably the first castle in the British Isles built as an artillery fort. It had "D-shape" bastions (strong parts of the wall that stick out) that could better resist cannon fire and where artillery could be placed. Towards the end of this period, royal builders in Scotland adopted European Renaissance styles for castle design. The grandest buildings of this type were the royal palaces at Linlithgow, Holyrood, Falkland, and the rebuilt Stirling Castle, which James IV started. A strong influence from France and the Netherlands can be seen in the popular design of a square courtyard with stair-turrets at each corner. However, these were adapted to Scottish styles and materials (especially stone and harl, a type of roughcast plaster).

Siege Weapons and Cannons

The Wars of Independence brought the first recorded uses of large mechanical artillery in Scotland. Edward I used many siege engines. These were carefully built, moved, set up, taken apart, and stored to be used again. This started with the siege of Caerlaverock Castle in 1300. After an initial attack failed, a small rock-throwing engine was used, while three large engines (probably trebuchets, which used a counter-weight) were built. Their destruction of the walls made the defenders lose hope and forced them to surrender. Edward's armies used several such engines, often given names. "Warwolf", one of 17 used to capture Stirling Castle in 1304, is the most famous (it's thought to be the largest trebuchet ever built). They also used lighter bolt-shooting balistas, tall siege towers called belfries, and once a covered sow (a type of siege shelter). Some of these were provided by Robert Earl of Carrick, who would become Robert I, and was on the English side at the time.

Scottish armies, with fewer resources and less experience, usually relied on direct attacks, blockades, and tricks to capture forts. Robert I is known to have used siege engines against the English, but often without much success, like at Carlisle in 1315, where his siege tower got stuck in the mud. The difference in siege technology is seen as a reason why Robert I decided to destroy castles.

Edward I had the main ingredients for gunpowder shipped to Stirling in 1304. This was probably to make a type of Greek fire to be shot into the town in clay pots by siege engines. The English probably had gunpowder cannons in the 1320s, and the Scots by the 1330s. The first clear record of their use in Britain was when Edward III besieged Berwick in 1333, where cannons were used alongside mechanical siege engines. The Scots probably first used them against Stirling Castle in 1341.

Gunpowder artillery began to completely replace mechanical engines in the late 1300s. The Stewarts tried to build up their own artillery, like the French and English kings. The failed siege of Roxburgh in 1436 under James I was probably the first time the Scots seriously used artillery. James II had a royal gunner and received gifts of artillery from Europe, including two giant cannons made for Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. One of these, Mons Meg, still exists today. Even though these might have been old-fashioned in Europe, they were impressive military technology when they reached Scotland. James II's love for artillery cost him his life and showed some of the dangers of early cannons, when a gun exploded at the siege of Roxburgh in 1460. James III also had bad luck when artillery sent from Sigismund, Archduke of Austria sank in a storm on its way to Scotland in 1481.

James IV brought in experts from France, Germany, and the Netherlands and set up a foundry (a place to make metal objects) in 1511. Edinburgh Castle had an artillery house where visitors could see cannons being made for what became a strong artillery force. This allowed him to send cannons to France and Ireland and quickly capture Norham Castle in the Flodden campaign. However, his 18 heavy cannons had to be pulled by 400 oxen, which slowed down the Scottish army. They also proved ineffective against the English guns, which had a longer range and fired smaller cannonballs at the Battle of Flodden.

English naval power was very important for Edward I's successful campaigns in Scotland from 1296. He mostly used merchant ships from England, Ireland, and his allies in the Islands to transport and supply his armies. Part of the reason for Robert I's success was his ability to use ships from the Islands. After the Flemings were expelled from England in 1303, he gained the support of a major naval power in the North Sea.

The growth of naval power allowed Robert to successfully defeat English attempts to capture him in the Highlands and Islands. It also allowed him to blockade major English-controlled forts at Perth and Stirling. The blockade of Stirling forced Edward II to try to relieve it, which led to the English defeat at Bannockburn in 1314. Scottish naval forces allowed invasions of the Isle of Man in 1313 and 1317, and Ireland in 1315. They were also key in the blockade of Berwick, which led to its fall in 1318.

After Scotland became independent, Robert I focused on building up a Scottish navy. This was mostly on the west coast. Records from 1326 show that his nobles in that region had a feudal duty to help him with their ships and crews. Towards the end of his reign, he oversaw the building of at least one royal man-of-war (a warship) near his palace at Cardross on the River Clyde. In the late 1300s, naval warfare with England was mostly carried out by hired Scottish, Flemish, and French merchant ships and privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships).

James I took a greater interest in sea power. After he returned to Scotland in 1424, he set up a shipbuilding yard at Leith, a place for marine supplies, and a workshop. King's ships were built and equipped there to be used for trade as well as war. One of these ships went with him on his trip to the Islands in 1429. The job of Lord High Admiral was probably created around this time. In his fights with his nobles in 1488, James III got help from his two warships, the Flower and the King's Carvel (also known as the Yellow Carvel).

James IV started a new era for the navy. He founded a harbor at Newhaven in May 1504, and two years later ordered a dockyard to be built at the Pools of Airth. The upper parts of the Forth River were protected by new forts on Inchgarvie. The king got a total of 38 ships for the Royal Scottish Navy, including the Margaret and the large ship Michael or Great Michael. The Great Michael, built at great cost at Newhaven and launched in 1511, was about 73 meters long, weighed 1,000 tons, had 24 cannons, and was, at that time, the largest ship in Europe. Scottish ships had some success against privateers, went with the king on his trips to the islands, and got involved in conflicts in Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea. In the Flodden campaign, the fleet had 16 large and 10 smaller ships. After a raid on Carrickfergus in Ireland, it joined up with the French fleet and had little impact on the war. After the disaster at Flodden, the Great Michael, and perhaps other ships, were sold to the French. The king's ships stopped appearing in royal records after 1516.

|

See also