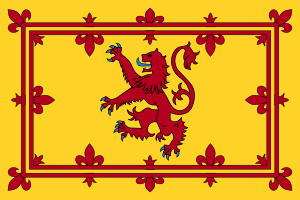

Scotland in the High Middle Ages facts for kids

The High Middle Ages of Scotland was a time in Scotland's history. It lasted from the year 900 AD, when King Domnall II died, until 1286, when King Alexander III passed away. Alexander's death later led to the Wars of Scottish Independence.

Around the year 900, different kingdoms existed in what is now Scotland. Scandinavian people had a lot of power in the northern and western islands. Brythonic culture was strong in the southwest. The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria was in the southeast. The Pictish and Gaelic Kingdom of Alba was in the east, north of the River Forth.

By the 900s and 1000s, Gaelic culture became very important in northern Great Britain. The Gaelic kingdom of Alba, also called Scotia or "Scotland," grew stronger. Starting from its base in the east, this kingdom slowly took control of lands to the south, west, and much of the north. It had a thriving culture, part of the larger Gaelic-speaking world. Its economy relied on farming and trade.

After the 1100s, during the time of King David I, Scottish kings became more like Scoto-Normans. They preferred French culture over native Scottish ways. This led to French ideas and rules, like Canon law, spreading across Scotland. The first towns, called burghs, also appeared then. As these towns grew, the Middle English language became more common.

However, the Norse-Gaelic west was also brought into Scotland. Many noble families of French and Anglo-French background started to adopt Gaelic ways. Scotland became more united as unique religious and cultural practices developed. By the end of this period, Scotland saw a "Gaelic revival." This helped create a strong Scottish national identity. By 1286, Scotland was more connected to its neighbours in England and Europe. However, some outsiders still saw Scotland as a wild place. By this time, the Kingdom of Scotland had borders very similar to modern Scotland.

Contents

Origins of the Kingdom of Alba

Around the year 900, many different groups lived in Scotland. The Pictish and Gaelic Kingdom of Alba had just joined together in the east. The Kingdom of the Isles, influenced by Scandinavians, grew in the west. Ragnall ua Ímair was a key leader then. We don't know exactly how much land he ruled in western and northern Scotland.

Dumbarton, the main city of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, was attacked in 870. This was a major attack. It might have put all of mainland Scotland under temporary control of the Uí Imair family. The southeast had become part of the English Kingdom of Bernicia/Northumbria in the 600s. Galloway in the southwest was a powerful area. Its ruler, Fergus, called himself "King of Galloway." In the northeast, the ruler of Moray was also called "king" in some old writings.

However, when Domnall mac Causantín died at Dunnottar in 900, he was the first to be called rí Alban (King of Alba). His kingdom was the start of what would become Scotland. In the 900s, the leaders of Alba began to tell a story. It explained how they became more Gaelic and less Pictish. This story, called MacAlpin's Treason, said that Cináed mac Ailpín wiped out the Picts in one quick takeover.

But today, historians don't believe this story. No old writings from that time mention such a conquest. Also, Pictland slowly became Gaelic over a long time, even before Cináed. We know this because Pictish rulers spoke Gaelic. They also supported Gaelic poets, and Gaelic words are found in old writings and place names. The change in identity might be because the Pictish language died out. Also, Causantín II may have made the Pictish Church more Scottish. The trauma from Viking attacks, especially in the Pictish heartland of Fortriu, also played a part.

Kingdom of the Isles

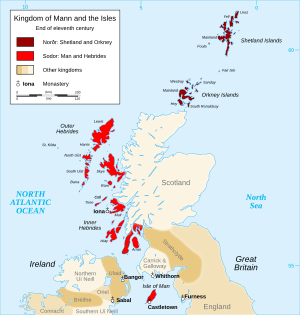

The Kingdom of the Isles included the Hebrides, the islands in the Firth of Clyde, and the Isle of Man. This kingdom existed from the 800s to the 1200s AD. The Norse people called these islands the Suðreyjar, meaning "Southern Isles." This was to tell them apart from the Norðreyjar or "Northern Isles" (Orkney and Shetland). The Earls of Orkney ruled the Northern Isles for the Norwegian crown during this time.

After Ragnall ua Ímair, Amlaíb Cuarán was another King of the Isles. He fought in the Battle of Brunanburh in 937 and also became King of Northumbria. Later Norse writings list other rulers like Gilli, Sigurd the Stout, Håkon Eiriksson, and Thorfinn Sigurdsson. They ruled the Hebrides as vassals of the Kings of Norway or Denmark.

Godred Crovan became the ruler of Dublin and Mann in 1079. From the early 1100s, the Crovan dynasty ruled as "Kings of Mann and the Isles" for about 50 years. Then, the kingdom split because of Somerled. His sons inherited the southern Hebrides. The Manx rulers kept the "north isles" for another century.

The North

Scandinavian influence in Scotland was probably strongest in the mid-1000s. This was during the time of Thorfinn Sigurdsson. He tried to create one large area stretching from Shetland to Man. The lands permanently held by Scandinavians in Scotland at that time were at least a quarter of modern Scotland's land area.

By the late 1000s, the Norwegian crown accepted that the Earls of Orkney held Caithness as a fiefdom from the Kings of Scotland. But its Norse character remained throughout the 1200s. Raghnall mac Gofraidh was given Caithness. This happened after he helped the Scottish king in a fight with Harald Maddadson, an earl of Orkney, in the early 1200s.

In the 800s, Orkney also controlled Moray. Moray was a semi-independent kingdom for much of this early period. The Moray rulers Macbeth (1040–1057) and his successor Lulach (1057–1058) ruled all of Scotland for a while. However, Scottish kings took control of Moray after 1130. This was when the local ruler, Óengus of Moray, was killed leading a rebellion. Another revolt in 1187 also failed.

Southwest Scotland

By the mid-900s, Amlaíb Cuarán controlled The Rhinns. The region got its modern name, Galloway, from the mix of Viking and Gaelic Irish settlers. Magnus Barelegs is said to have "subdued the people of Galloway" in the 1000s. Whithorn seems to have been a center for Norse-Irish craftspeople. They traded around the Irish Sea by the end of the first millennium. However, there isn't strong proof of many Norse (not Norse-Gael) settlements in the area.

The ounceland system, a way of measuring land, spread down the west coast. This included much of Argyll and most of the southwest, except for an area near the inner Solway Firth. In Dumfries and Galloway, place names show a mix of Gaelic, Norse, and Danish influences. The Danish influence likely came from contact with Danish lands in northern England. Although the Scots gained more control after the death of Gilla Brigte and Lochlann became ruler in 1185, Galloway wasn't fully part of Scotland until 1235. This happened after the rebellion of the Galwegians was crushed.

Strathclyde

The main language of Strathclyde and other parts of the Hen Ogledd (Old North) at the start of the High Middle Ages was Cumbric. This was a type of British language, similar to Old Welsh. Sometime after 1018 and before 1054, the Scots seem to have conquered the kingdom. This likely happened during the reign of Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, who died in 1034. At this time, Strathclyde reached as far south as the River Derwent.

In 1054, the English king Edward the Confessor sent Earl Siward of Northumbria against the Scots, who were then ruled by Macbeth. By the 1070s, or even earlier under Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, the Scots again controlled Strathclyde. However, William Rufus took the southern part in 1092. King Alexander I gave the territory to his brother David, who later became King David I, in 1107.

Kingdom of Alba or Scotia

Gaelic Kings: Domnall II to Alexander I

Domnall mac Causantín was nicknamed dásachtach, meaning "madman." This term also meant someone not in control of their actions in old Irish law. The long reign (900–942/3) of his successor Causantín is often seen as key to forming the Kingdom of Alba.

The time between the start of Máel Coluim I's rule and Máel Coluim mac Cináeda's was peaceful with the Wessex rulers of England. There was also a lot of fighting among Scottish royal families. Despite this, Scotland successfully expanded its lands. In 945, King Máel Coluim I received Strathclyde as part of a deal with King Edmund of England. But Máel Coluim lost control in Moray. Sometime during King Idulb's rule (954–962), the Scots captured the fortress called oppidum Eden, which is Edinburgh. Scottish control of Lothian grew stronger with Máel Coluim II's victory over the Northumbrians at the Battle of Carham (1018). The Scots probably had some power in Strathclyde since the late 800s. But the kingdom kept its own rulers, and it's not clear if the Scots were always strong enough to enforce their rule.

The reign of King Donnchad I from 1034 was full of failed military adventures. He was killed in a battle with men from Moray, led by Macbeth. Macbeth became king in 1040. Macbeth ruled for 17 years, peacefully enough that he could go on a pilgrimage to Rome. However, he was overthrown by Máel Coluim, Donnchad's son. Máel Coluim defeated Macbeth's stepson and successor Lulach a few months later to become King Máel Coluim III. Later medieval stories made Donnchad's rule look good and Macbeth's look bad. William Shakespeare used this changed history in his play Macbeth, showing both the king and his queen consort, Gruoch, in a negative light.

It was Máel Coluim III, not his father Donnchad, who did more to create the royal family that ruled Scotland for the next two centuries. He had many children, perhaps as many as 12. He married the widow or daughter of Thorfinn Sigurdsson. Later, he married the Anglo-Hungarian princess Margaret, who was the granddaughter of Edmund Ironside. Even though he had an Anglo-Saxon royal wife, Máel Coluim often raided England for slaves. This added to the troubles of the English after the Norman Conquest of England and the Harrying of the North. An old writer, Marianus Scotus, wrote that "the Gaels and French devastated the English; and [the English] were dispersed and died of hunger; and were compelled to eat human flesh."

Máel Coluim's Queen Margaret was the sister of Edgar Ætheling, who claimed the English throne. This marriage and Máel Coluim's raids on northern England caused the Norman rulers of England to get involved in Scotland. King William the Conqueror invaded, and Máel Coluim submitted to him. He gave his oldest son Donnchad as a hostage. From 1079 onwards, both sides raided across the border. Máel Coluim himself and Edward, his eldest son by Margaret, died in one of these raids in the Battle of Alnwick in 1093.

Traditionally, his brother Domnall Bán would have been Máel Coluim's successor. But it seems Edward, his eldest son by Margaret, was his chosen heir. With Máel Coluim and Edward dead in the same battle, and his other sons in Scotland still young, Domnall became king. However, Donnchad II, Máel Coluim's eldest son by his first wife, got some help from William Rufus and took the throne. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, his English and French followers were killed. Donnchad II himself was killed later that year (1094) by Domnall's ally Máel Petair of Mearns. In 1097, William Rufus sent another of Máel Coluim's sons, Edgar, to become king. Domnall Bán's death secured the kingship for Edgar, and a period of peace followed. The reigns of Edgar and his successor Alexander are not as well known as those of later kings. Edgar's most famous act was sending a camel (or perhaps an elephant) to his fellow Gael Muircheartach Ua Briain, the High King of Ireland. When Edgar died, Alexander became king, while his youngest brother David became Prince of Cumbria.

Scoto-Norman Kings: David I to Alexander III

The time between David I becoming king and Alexander III's death was marked by Scotland relying on and having good relations with the Kings of England. This period was a time of great change, part of a bigger trend called "Europeanisation." During this time, royal power was successfully established across most of modern Scotland. After David I, and especially during the reign of William I, Scotland's kings were not always fond of the culture of most of their people. As Walter of Coventry wrote, "The modern kings of Scotland consider themselves French, in their background, customs, language, and culture. They keep only French people in their household and followers, and have made the Gaels completely subservient."

This situation had consequences. After William was captured at Alnwick in 1174, the Scots turned on the few Middle English-speakers and French-speakers among them. William of Newburgh said the Scots first attacked the Scottish-English in their own army. Newburgh reported similar events happening in Scotland itself. Walter Bower, writing centuries later about the same events, confirmed that "a most terrible and widespread persecution of the English took place in both Scotland and Galloway."

The first strong resistance to the Scottish kings was perhaps the revolt of Óengus, the Mormaer of Moray. Other important people who resisted the expanding Scottish kings were Somerled, Fergus of Galloway, Gille Brigte, Lord of Galloway, and Harald Maddadsson. Also, two family groups known as the MacHeths and the MacWilliams caused trouble. The threat from the MacWilliams was so serious that, after they were defeated in 1230, the Scottish crown ordered the public execution of a baby girl. She was the last of the MacWilliam family line. According to the Lanercost Chronicle:

the same Mac-William's daughter, who had not long left her mother's womb, innocent as she was, was put to death, in the burgh of Forfar, in view of the market place, after a proclamation by the public crier. Her head was struck against the column of the market cross, and her brains dashed out.

Many of these resistors worked together. They got support not just from the Gaelic areas of Galloway, Moray, Ross, and Argyll, but also from eastern "Scotland-proper" and other parts of the Gaelic world. However, by the end of the 1100s, the Scottish kings had gained enough power. They could use native Gaelic lords outside their usual control to do their work. The most famous examples are Lochlann, Lord of Galloway and Ferchar mac in tSagairt.

By the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were strong enough to take over the rest of the western coast. They did this after Haakon Haakonarson's failed invasion and the draw at the Battle of Largs. This led to the Treaty of Perth in 1266. The conquest of the west, the creation of the Mormaerdom of Carrick in 1186, and the absorption of the Lordship of Galloway after the Galwegian revolt of Gille Ruadh in 1235 meant that Gaelic speakers under the Scottish king made up most of the population during the so-called Norman period. The mixing of Gaelic, Norman, and Saxon cultures that began to happen may have helped King Robert I win during the Wars of Independence, which started soon after Alexander III's death.

Geography of Medieval Scotland

At the start of this period, the Kingdom of Alba was much smaller than modern Scotland. Even as lands were added in the 900s and 1000s, the name Scotia only referred to the area between the River Forth, the central Grampians, and the River Spey. It only began to describe all lands under the Scottish crown from the mid-1100s. By the late 1200s, after the Treaty of York (1237) and Treaty of Perth (1266) set the borders with England and Norway, Scotland's boundaries were very close to today's. After this time, both Berwick and the Isle of Man were lost to England. Orkney and Shetland were gained from Norway in the 1400s.

The area that became Scotland is divided by its land into five main regions: the Southern Uplands, Central Lowlands, the Highlands, the North-east coastal plain, and the Islands. Mountains, large rivers, and marshes further divided some of these regions. Most regions had strong cultural and economic links to other places: England, Ireland, Scandinavia, and mainland Europe. Travel within the country was hard, and Scotland didn't have one clear central city. Dunfermline became a major royal center during Malcolm III's reign. Edinburgh started to hold royal records during David I's reign. But because it was close to and vulnerable to England, it didn't become a formal capital during this period.

Alba's expansion into the larger Kingdom of Scotland happened slowly. It involved conquering new lands and stopping rebellions. It also meant extending the king's power by placing effective royal agents. Nearby independent kings became subject to Alba and eventually disappeared from records. In the 800s, the term mormaer, meaning "great steward," appeared in records. It described the rulers of Moray, Strathearn, Buchan, Angus, and Mearns. They might have acted as "border lords" for the kingdom to fight the Viking threat. Later, the process of uniting the country is linked to feudalism introduced by David I. Especially in the east and south, where the king's power was strongest, this meant setting up lordships, often based in castles. It also created administrative sheriffdoms, which were built on top of the local thegn system. The English word earl and Latin comes also began to replace mormaers in records. The result was a "hybrid kingdom." In it, Gaelic, Anglo-Saxon, Flemish, and Norman parts all came together under its "Normanised," but still native, lines of kings.

Economy and Society

Economy

Scotland's economy during this time was mostly about farming and local trade over short distances. There was also more foreign trade and wealth gained from military raids. By the end of this period, coins started to replace bartering goods. But for most of this time, people traded without using metal money.

Most of Scotland's farming wealth came from raising animals (pastoralism), rather than growing crops (arable farming). Crop farming grew a lot during the "Norman period." But there were differences across the country. Low-lying areas had more crop farming than high-lying areas like the Highlands, Galloway, and the Southern Uplands. Galloway, as historian G. W. S. Barrow said, "already famous for its cattle, was so overwhelmingly pastoral, that there is little evidence in that region of land under any permanent cultivation, save along the Solway coast." The average amount of land a farmer (husbandman) used in Scotland might have been about 26 acres. Native Scots preferred raising animals. Gaelic lords were happier to give away more land to French and Middle English-speaking settlers. They held onto upland regions strongly. This might have helped create the Highland/Galloway-Lowland division that appeared in Scotland later in the Middle Ages.

The main way of measuring land in Scotland was the davoch (meaning "vat"). It was called the arachor in Lennox and also known as the "Scottish ploughgate." In English-speaking Lothian, it was simply called a ploughgate. It might have been about 104 acres, divided into 4 raths. Cattle, pigs, and cheeses were among the main foods. There was also a wide range of other products, including sheep, fish, rye, barley, beeswax, and honey.

David I started the first official towns (burghs) in Scotland. He copied the town rules and Leges Burgorum (laws covering almost every part of life and work) almost exactly from the English customs of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. Early townspeople were usually Flemish, English, French, and German, rather than Gaelic Scots. The words used in the burghs were all from Germanic and French languages. The councils that ran each burgh were called lie doussane, meaning "the dozen."

Population and Language

We don't know the exact population of Scotland during this period. The first reliable information from 1755 shows Scotland had 1,265,380 people. The best guesses for the High Middle Ages are between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people. The population likely grew from a low point to a high point.

Most people in Scotland during this time spoke the Gaelic language. It was simply called Scottish then, or in Latin, lingua Scotica. Other languages spoken were Old Norse and English. The Cumbric language disappeared sometime between 900 and 1100. Pictish might have survived into this period, but there isn't much proof.

After David I became king, or perhaps even before, Gaelic stopped being the main language of the royal court. From his reign until the end of the period, Scottish kings probably preferred the French language. This is shown by reports from old writings, literature, and translations of official documents into French. English, along with French and Flemish, became the main language of Scottish towns. However, these towns were, in historian Barrow's words, "scarcely more than villages... numbered in hundreds rather than thousands."

Society

This is a general idea based on early Gaelic law books. The words used in Scottish Latin writings were very different.

- Nemed (sacred person, highest rank)

- Ard rí (high king)

- Rí ruirech (provincial king)

- Rí túath (tribal king)

- Flaith (lord)

- Nemed (non-rulers)

- Clerics (church leaders)

- Fili (poets)

- Dóernemid (meaning "base Nemed")

- Brithem (tradesman, harpist, etc)

- Saoirseach (freeman)

- Bóaire (cattle lord)

- Ócaire (little lord)

- Fer midboth (young person, partly independent)

- Fuidir (partly free person)

- Unfree

- Bothach (serf, tied to the land)

- Senchléithe (hereditary serf, family tied to land)

- Mug (slave)

An old legal document called Laws of the Brets and Scots, probably written during David I's reign, shows how important family groups were. It explains that families could get payment if one of their members was killed. It also lists five levels of people: King, mormaer, toísech, ócthigern, and neyfs. The highest rank below the king, the mormaer ("great officer"), were probably about a dozen regional rulers. This title was later replaced by the English term earl. Below them, the toísech (leader) seemed to manage areas of the king's land, or land belonging to a mormaer or abbot. They would have held large estates, sometimes called shires. This title was probably like the later thane. The lowest free rank mentioned by the Laws of the Brets and Scots, the ócthigern (meaning "little" or "young lord"), is a term the text doesn't translate into French.

There were probably many free peasant farmers, called husbandmen or bondmen, in the south and north of the country. But there were fewer in the lands between the Forth and Sutherland until the 1100s. Then, landowners started to encourage this class by paying better wages and bringing in people from other areas. Below the husbandmen, a class of free farmers with smaller pieces of land developed. These included cottars and grazing tenants (gresemen). The non-free naviti, neyfs, or serfs had different types of service. Their terms came from Irish practices. These included cumelache, cumherba, and scoloc. They were tied to a lord's estate and couldn't leave without permission. But records show they often ran away for better wages or work in other regions or in the growing towns.

The introduction of feudalism from David I's time brought new ways of holding land. People held land from the king, or a higher lord, in exchange for loyalty and services, usually military. This also created sheriffdoms, which were placed over the local thanes. However, feudalism existed alongside the old system of landholding. It's not clear how this change affected the lives of ordinary free and unfree workers. In some places, feudalism might have tied workers more closely to the land. But because Scottish farming was mostly about raising animals, it might have been hard to set up a manorial system like in England. Duties seemed to be limited to occasional work, seasonal payments of food, offering hospitality, and money rents.

Law and Government

Early Gaelic law books, first written down in the 800s, show a society very focused on family ties, social standing, honour, and controlling blood feuds. Scottish common law began to form at the end of this period. It combined Gaelic and Celtic law with practices from Anglo-Norman England and Europe. In the 1100s, and certainly in the 1200s, strong European legal ideas began to have more effect. These included Canon law and various Anglo-Norman practices. Law among the native Scots before the 1300s is not always well recorded. But knowing a lot about early Gaelic Law helps us understand it.

In the oldest Scottish legal document we have, there's a text called Leges inter Brettos et Scottos. This document is in Old French. It was almost certainly a French translation of an earlier Gaelic document. It kept many Gaelic legal terms that were not translated. Later medieval legal documents, written in both Latin and Middle English, contain more Gaelic legal terms. Examples include slains (Old Irish slán or sláinte; meaning exemption) and cumherba (Old Irish comarba; meaning church heir).

A Judex (plural judices) shows a link to the old Gaelic lawmen called Brehons today. People holding this office almost always had Gaelic names north of the Forth or in the southwest. Judices were often royal officials. They oversaw courts run by nobles, abbots, and other lower-ranking "courts." However, the main law official in the Scottish Kingdom after David I was the Justiciar. This person held courts and reported directly to the king. Usually, there were two Justiciars, divided by language areas: the Justiciar of Scotia and the Justiciar of Lothian. Sometimes Galloway also had its own Justiciar.

The offices of Justiciar and Judex were just two ways Scottish society was governed. Earlier, the king gave power to hereditary native "officers" like the Mormaers/Earls and Toísechs/Thanes. It was a government based on giving gifts and having poets who knew the law. There were also public courts, called comhdhail. Dozens of place names throughout eastern Scotland show where these meetings happened.

In the Norman period, sheriffdoms and sheriffs, and to a lesser extent, bishops, became more important. Sheriffs helped the King effectively manage royal land. During David I's reign, royal sheriffs were set up in the king's main personal territories. These were, roughly in order, at Roxburgh, Scone, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Stirling, and Perth. By the reign of William I, there might have been about 30 royal sheriffdoms. These included ones at Ayr and Dumfries, which were key places on the borders of Galloway-Carrick. As the number and spread of sheriffdoms grew, so did royal control. By the end of the 1200s, sheriffdoms were in far-off western places like Wigtown, Kintyre, Skye, and Lorne. Through these, the 1200s Scottish king had more control over Scotland than any of his later medieval successors.

The king himself traveled a lot and didn't have one "capital" city. However, Scone played a very important role. By old tradition, all Scottish kings in this period had to be crowned there by the Mormaers of Strathearn and Fife. Although King David I tried to make Roxburgh a capital, in the 1100s and 1200s, more official documents were issued at Scone than anywhere else. Other popular places were nearby Perth, Stirling, Dunfermline, and Edinburgh. In the very early part of this era, Forres and Dunkeld seem to have been the main royal homes.

Records from the lands held by Scandinavians are much less detailed. Udal law was the basis of their legal system. We know that the Hebrides were taxed using the Ounceland measure. Althings were outdoor government meetings. They met with the jarl (earl) present, and almost all free men could attend. At these meetings, decisions were made, laws were passed, and complaints were settled. Examples include Tingwall and Law Ting Holm in Shetland, Dingwall in Easter Ross, and Tynwald on the Isle of Man.

Warfare

Land Warfare

By the 1100s, lords and the king could call on larger groups of men for big campaigns. This became known as the "common" (communis exercitus) or "Scottish army" (exercitus Scoticanus). This was because everyone who held certain units of land had to serve. Later rules said the common army was made up of all able-bodied free men aged 16 to 60, with 8 days' warning. It produced many men who served for a short time, usually as archers and spearmen with little or no armour. In this period, the earls continued to gather these men. They often led their men in battle, as happened in the Battle of the Standard in 1138. This common army would continue to make up most of Scotland's national armies, potentially bringing tens of thousands of men for short conflicts, even into the early modern era.

There were also duties that produced smaller numbers of feudal troops. The Davidian Revolution of the 1100s, according to Geoffrey Barrow, brought "fundamental innovations in military organization." These included the knight's fee (land given for knight service), homage and fealty (oaths of loyalty), as well as building castles and regularly using professional cavalry. Knights held castles and estates in exchange for service, providing troops for 40 days at a time. David's Norman followers and their groups could provide perhaps 200 mounted and armoured knights. But most of his forces were the "common army" of poorly armed foot soldiers. These soldiers were good at raiding and guerrilla warfare. Although such troops were only sometimes able to stand up to the English in open battle, they did manage to do so critically in the wars of independence at Stirling Bridge in 1297 and Bannockburn in 1314.

Marine Warfare

The Viking attacks on the British Isles were successful because of their strong sea power. This allowed them to create powerful sea-based kingdoms in the north and west. In the late 900s, the Alban forces won a naval battle against Vikings at "Innisibsolian" (possibly near the Slate Islands of Argyll). This was an unusual defeat for the Norse. In 962, Ildulb mac Causantín, King of Scots, was killed fighting the Norse near Cullen at the Battle of Bauds. Although there's no proof of permanent Viking settlements on Scotland's east coast south of the Moray Firth, raids and even invasions certainly happened. Dunnottar was captured during the reign of Domnall mac Causantín. The Orkneyinga saga records an attack on the Isle of May by Sweyn Asleifsson and Margad Grimsson.

The long-ship, which was key to their success, was a graceful, long, narrow, light wooden boat. It had a shallow bottom designed for speed. This shallow design allowed it to travel in water only one meter deep and land on beaches. Its light weight meant it could be carried over land between bodies of water (portages). Longships were also pointed at both ends. This allowed the ship to quickly change direction without turning around. In the Gàidhealtachd (Gaelic-speaking areas), they were eventually replaced by the Birlinn, highland galley, and lymphad. These ships, in increasing order of size, started using a rudder at the back instead of a steering board from the late 1100s.

Groups of ships were raised through duties called a ship-levy. This was done through the system of ouncelands and pennylands. Some believe this system dates back to the Dál Riata muster system, but it was probably introduced by Scandinavian settlers. Later evidence suggests that providing ships for war became linked to military feudal obligations. Viking naval power was weakened by conflicts between the Scandinavian kingdoms. But it became strong again in the 1200s when Norwegian kings started building some of the largest ships seen in Northern European waters. This lasted until Haakon Haakonarson's failed expedition in 1263. After that, the Scottish crown became the most powerful force in the region.

Christianity and the Church

By the 900s, all of northern Britain was Christian. The only exceptions were the Scandinavian north and west, where the church had lost ground due to Norse settlement.

Saints

Like every other Christian country, one of the main features of medieval Scottish Christianity was the worship of Saints. Saints of Irish origin who were especially honoured included various figures called St Faelan and St. Colman, and saints Findbar and Finan. The most important missionary saint was Columba. He became a national figure in the combined Scottish and Pictish kingdom. A new center for some of his relics was set up in the east at Dunkeld by Kenneth I. He remained a major figure into the 1300s. William I started a new religious house at Arbroath Abbey, and the relics in the Monymusk Reliquary were given to the Abbot's care.

Local saints remained important for local identities. In Strathclyde, the most important saint was St Kentigern. In Lothian, it was St Cuthbert. After his death around 1115, people in Orkney, Shetland, and northern Scotland started to worship Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney. The worship of St Andrew in Scotland began on the East coast with the Pictish kings as early as the 700s. The shrine, which from the 1100s was said to contain the saint's relics brought to Scotland by Saint Regulus, started to attract pilgrims from Scotland, England, and further away. By the 1100s, the site at Kilrymont was simply known as St. Andrews. It became more and more linked with Scottish national identity and the royal family. It became a renewed focus for devotion with the support of Queen Margaret. She also became important after she was made a saint in 1250. Her remains were ceremonially moved to Dunfermline Abbey, making her one of the most respected national saints.

Organisation

There is some proof that Christianity spread into the Viking-controlled Highlands and Islands before the official conversion in the late 900s. There are many islands called Pabbay or Papa in the Western and Northern Isles. These names might mean "hermit's" or "priest's isle" from this period. Changes in grave goods and the use of Viking place names with "-kirk" also suggest that Christianity had begun to spread before the official conversion.

According to the Orkneyinga Saga, the Northern Isles became Christian in 995. This happened when Olav Tryggvasson stopped at South Walls on his way from Ireland to Norway. The King called the jarl Sigurd the Stout and said, "I order you and all your subjects to be baptised. If you refuse, I'll have you killed on the spot and I swear I will ravage every island with fire and steel." Not surprisingly, Sigurd agreed. The islands became Christian very quickly, getting their own bishop in the early 1000s. Elsewhere in Scandinavian Scotland, the records are less clear. There was a Bishop of Iona until the late 900s. Then there's a gap of over a century, possibly filled by the Bishops of Orkney, before the first Bishop of Mann was appointed in 1079.

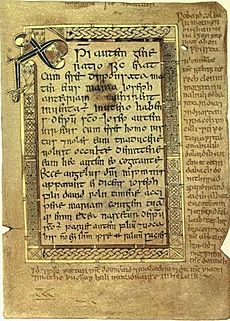

At the start of this period, Scottish monasteries were mainly run by monks called Céli Dé (meaning "vassals of God"), also known as culdees. At St Andrews and other places, Céli Dé abbeys are recorded. The round towers at Brechin and Abernethy show Irish influence. Gaelic monasticism was active and expanding for much of the period. Dozens of monasteries, often called Schottenklöster, were founded by Gaelic monks in Europe.

The introduction of the European style of monasticism to Scotland is linked to Queen Margaret, the wife of Máel Coluim III. However, her exact role is not clear. She talked with Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury. He provided a few monks for a new Benedictine abbey at Dunfermline (around 1070). Later foundations under Margaret's sons, Kings Edgar, Alexander I, and especially David I, tended to be of the reformed type that followed the lead set by Cluny. These stressed the original Benedictine values of poverty, chastity and obedience, but also quiet prayer and serving Mass. Many reformed Benedictine, Augustinian, and Cistercian houses followed these ideas in various ways.

Before the 1100s, most Scottish churches had groups of clergy who served a wide area. They were often connected by their devotion to a specific missionary saint. From this period, local landowners, perhaps following David I's example, began to adopt the European practice of building churches on their land for local people. They would give land and a priest to these churches. This started in the south, spread to the north-east, and then to the west. It was almost universal by the first survey of the Scottish Church for papal taxes in 1274. The management of these parishes was often given to local monasteries.

Scotland had little clear church structure before the Norman period. There were bishoprics based on various old churches. But some are very unclear in the records, and there seem to be long times when there was no bishop. From around 1070, during Malcolm III's reign, there was a "Bishop of Alba" living at St. Andrews. But it's not clear what power he had over the other bishops. After the Norman Conquest of England, the Archbishops of both Canterbury and York each claimed to be superior to the Scottish church. The church in Scotland gained independent status after the Papal Bull of Celestine III (Cum universi, 1192). By this, all Scottish bishoprics except Galloway were officially independent of York and Canterbury. However, unlike Ireland, which had been given four Archbishoprics in the same century, Scotland received no Archbishop. The whole Ecclesia Scoticana, with individual Scottish bishoprics (except Whithorn/Galloway), became the "special daughter of the see of Rome." In practice, it was run by special councils made up of all its bishops, with the bishop of St Andrews becoming the most important leader.

Culture

As a mostly Gaelic society, most Scottish cultural practices during this period were very similar to those in Ireland. Some Pictish influences were also present. After David I, the French-speaking kings brought in cultural practices popular in Anglo-Norman England, France, and other places. Like in all old societies, storytelling was popular. The English scholar D. D. R. Owen, who studies the literature of this time, writes that "Professional storytellers would travel from court to court. Some of them would have been native Scots, no doubt telling legends from the ancient Celtic past... in Gaelic when appropriate, but in French for most of the new nobility." Almost all of these stories are lost. However, some have survived in Gaelic or Scots oral tradition.

One type of oral culture that is very well known from this period is genealogy (family histories). Dozens of Scottish genealogies from this time still exist. They cover everyone from the Mormaers of Lennox and Moray to the Scottish king himself. Scotland's kings kept an ollamh righe, a royal high poet. This poet had a permanent place in all medieval Gaelic lordships. Their job was to recite genealogies when needed, for events like coronations.

Before the reign of David I, the Scots had a thriving group of writers. They regularly produced texts in both Gaelic and Latin. These texts were often sent to Ireland and other places. Dauvit Broun has shown that a Gaelic writing elite survived in the eastern Scottish lowlands. This was in places like Loch Leven and Brechin into the 1200s. However, most surviving records are written in Latin. Their authors would usually translate local words into Latin. So, historians have to research a Gaelic society described using Latin words. Even names were translated into more common European forms. For example, Gilla Brigte became Gilbert, Áed became Hugh, and so on.

As for written literature, there might be more medieval Scottish Gaelic literature than often thought. Almost all medieval Gaelic literature has survived because it was kept in Ireland, not in Scotland. Thomas Owen Clancy has almost proven that the Lebor Bretnach, also called the "Irish Nennius," was written in Scotland. It was probably written at the monastery in Abernethy. Yet this text only exists in manuscripts kept in Ireland. Other surviving literary work includes that of the very productive poet Gille Brighde Albanach. Around 1218, Gille Brighde wrote a poem called Heading for Damietta. It described his experiences during the Fifth Crusade. In the 1200s, French became a popular literary language. It produced the Roman de Fergus, one of the earliest non-Celtic stories to survive from Scotland.

There is no existing literature in the English language from this era. There is some Norse literature from Scandinavian parts, like Darraðarljóð. This story is set in Caithness and is a "powerful mix of Celtic and Old Norse ideas." The famous Orkneyinga Saga, which tells the early history of the Earldom of Orkney, was written down in Iceland.

In the Middle Ages, Scotland was known for its musical talent. Gerald of Wales, a medieval clergyman and writer, explained the connection between Scottish and Irish music:

Scotland, because of her affinity and intercourse [with Ireland], tries to imitate Ireland in music and strives in emulation. Ireland uses and delights in two instruments only, the harp namely, and the tympanum. Scotland uses three, the harp, the tympanum and the crowd. In the opinion, however, of many, Scotland has by now not only caught up on Ireland, her instructor, but already far outdistances her and excels her in musical skill. Therefore, [Irish] people now look to that country as the fountain of the art.

Playing the harp (clarsach) was especially popular with medieval Scots. Half a century after Gerald's writing, King Alexander III had a royal harpist at his court. Of the three medieval harps that still exist, two come from Scotland (Perthshire), and one from Ireland. Singers also had a royal role. For example, when the king of Scotland traveled through the area of Strathearn, it was custom for him to be greeted by seven female singers. They would sing to him. When Edward I approached the borders of Strathearn in the summer of 1296, he was met by these seven women. They "accompanied the King on the road between Gask and Ogilvie, singing to him, as was the custom in the time of the late Alexander kings of Scots."

How Outsiders Saw Scotland

The Irish thought of Scotland as a less important place. Others thought of it as a strange or wild place. "Who would deny that the Scots are barbarians?" was a question asked in the 1100s by the Anglo-Flemish writer of De expugnatione Lyxbonensi (On the Conquest of Lisbon). A century later, Louis IX of France was said to have told his son, "I would prefer that a Scot should come from Scotland and govern the people well and faithfully, than that you, my son, should be seen to govern badly."

This way of describing the Scots was often for political reasons. Many of the writers who were most critical lived in areas often attacked by the Scots. English and French accounts of the Battle of the Standard contain many stories of Scottish actions. For example, Henry of Huntingdon wrote that the Scots: "cleft open pregnant women, and took out the unborn babes; they tossed children upon the spear-points, and beheaded priests on altars: they cut the head of crucifixes, and placed them on the trunks of the slain, and placed the heads of the dead upon the crucifixes. Thus wherever the Scots arrived, all was full of horror and full of savagery."

A less critical view was given by Guibert of Nogent during the First Crusade. He met Scots and wrote: "You might have seen a crowd of Scots, a people savage at home but unwarlike elsewhere, descend from their marshy lands, with bare legs, shaggy cloaks, their purse hanging from their shoulders; their copious arms seemed ridiculous to us, but they offered their faith and devotion as aid."

There was also a common belief that Scotland-proper was an island, or at least a peninsula. It was known as Scotia, Alba, or Albania. Matthew Paris, a Benedictine monk and mapmaker, drew a map like this in the mid-1200s and called the "island" Scotia ultra marina. A later medieval Italian map shows all of Scotland in this way. The Arab geographer al-Idrisi shared this view: "Scotland adjoins the island of England and is a long peninsula to the north of the larger island. It is uninhabited and has neither town nor village. Its length is 150 miles."

National Identity

During this period, most Scots did not use the word "Scot" to describe themselves, except to foreigners. Among foreigners, it was the most common word. The Scots called themselves Albanach or simply Gaidel. Both "Scot" and Gaidel were ethnic terms that linked them to most of the people in Ireland. As the writer of De Situ Albanie noted in the early 1200s: "The name Arregathel [Argyll] means margin of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called 'Gattheli'."

Likewise, people in English and Norse-speaking areas were ethnically linked with other parts of Europe. At Melrose, people could read religious writings in English. In the later 1100s, the Lothian writer Adam of Dryburgh described Lothian as "the Land of the English in the Kingdom of the Scots." In the Northern Isles, the Norse language developed into the local Norn. This language lasted until the late 1700s, when it finally died out. Norse may also have been spoken until the 1500s in the Outer Hebrides.

Scotland gained a unity that went beyond Gaelic, English, Norman, and Norse ethnic differences. By the end of the period, the Latin, Norman-French, and English word "Scot" could be used for any subject of the Scottish king. Scotland's kings, who spoke many languages, and its mixed Gaelic and Scoto-Norman nobility all became part of the "Community of the Realm." In this community, ethnic differences were less divisive than in Ireland and Wales.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |