Fergus of Galloway facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fergus of Galloway |

|

|---|---|

| Lord of Galloway | |

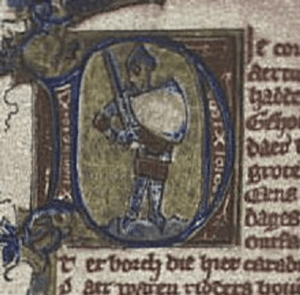

Fourteenth-century illuminated initial of Leiden University Library Letterkunde 191 (Roman van Ferguut). The knight depicted in the initial may represent an Arthurian character who in turn may be named after Fergus himself.

|

|

| Died | 12 May 1161 |

| Issue |

|

Fergus of Galloway (died 12 May 1161) was an important leader in the 1100s, known as the Lord of Galloway. His family background isn't fully known, but he might have had Norse-Gaelic roots. Fergus first appears in historical records around 1136. At that time, he witnessed an important document for David I, King of Scotland. Many historians believe Fergus was married to a daughter of Henry I, King of England, who was born outside of marriage. This daughter, possibly Elizabeth Fitzroy, might have been the mother of Fergus's three children.

Fergus made a strong alliance with Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles, by arranging for Óláfr to marry his daughter, Affraic. This marriage meant that many future leaders of the Crovan dynasty came from Fergus's family line. When Óláfr was killed by rival relatives, Galloway itself was attacked. However, Fergus's grandson, Guðrøðr Óláfsson, managed to take control of the Kingdom of the Isles. Both Fergus and his grandson were involved in military actions in Ireland. Later, Guðrøðr was overthrown by Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, Lord of Argyll. The fact that Fergus didn't seem to help Guðrøðr against Somairle might show that Fergus's own power was weakening. Records from that time suggest that Galloway was facing a lot of family conflicts.

Fergus lost his power in 1160. This happened after Malcolm IV, King of Scotland, settled some disagreements among his own powerful nobles. Malcolm then launched three military campaigns into Galloway. The exact reasons for this Scottish invasion are not clear. It's possible Fergus had been attacking Scottish lands. After the invasion, King Malcolm made a deal with Somairle. This could mean Somairle was either allied with Fergus against the Scots, or he helped Malcolm defeat Fergus. In any case, Fergus was forced to give up his power. He had to retire to the abbey of Holyrood, a monastery. He died the following year. His lands, the Lordship of Galloway, seem to have been divided between his sons, Gilla Brigte and Uhtred. After this, Scottish influence grew much stronger in Galloway.

Contents

Who Was Fergus's Family?

We don't know much about Fergus's early family. Old records don't mention his father's name. Later, his descendants didn't trace their family tree further back than him in their official documents. The fact that he was often called "of Galloway" in records suggests he led the most important family in that area. This was similar to his contemporary, Freskin, who was called de Moravia because he was a key figure in Moray.

A medieval story called Roman de Fergus might give us some clues. This Arthurian romance is set in southern Scotland and tells the story of a knight who might be Fergus himself. In this story, the knight's father has a name similar to Fergus's neighbor, Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, Lord of Argyll. This could mean Fergus's father had the same name. However, it's also possible the story just used common names from Galloway. The story itself might be a playful imitation of other famous tales, so it might not be a reliable source for history.

Even though his origins are unclear, Fergus might have had both Norse-Gaelic and native Gallovidian ancestors. People from Galloway traditionally looked more towards the Kingdom of the Isles than Scotland. His family's main lands seem to have been around the River Dee and the coast near Whithorn. These areas had a lot of Scandinavian settlers. Fergus died as an old man in 1161, which suggests he was born before the year 1100.

Fergus's Early Life and Power

Fergus first appears in records between 1136 and 1141. At that time, he and his son, Uhtred, witnessed a gift of land to a church in Glasgow. The exact size of the Lordship of Galloway in the 1100s isn't fully clear. Records show that Fergus and Uhtred gave many gifts of land in central Galloway, between the rivers Urr and Fleet. Later, Fergus's descendants gave lands in the Dee valley, which might mean their territory grew from this central area. There is also evidence that Fergus's rule extended into western Galloway. His descendants were connected to castle of Cruggleton and owned lands nearby.

Around 1140, a religious leader named Máel Máedoc Ua Morgair, Archbishop of Armagh, landed at Cruggleton while traveling. Although some sources connect this castle to the Scots, it's unlikely Scottish royal power reached that far. It's more likely Máel Máedoc visited the local lord, possibly Fergus himself. So, in the mid-1100s, Fergus's power seems to have been centered around Wigtown Bay and the mouth of the River Dee.

Gilla Brigte, who might have been Fergus's oldest child, later gained power from west of the river Cree. This could mean his mother came from an important family in that region. Such a marriage alliance could also explain Fergus's expansion westward. Around 1128, the Diocese of Whithorn (a church region) was re-established, possibly by Fergus. This might show he wanted to create a church area that covered all his lands. Fergus's growing power in western Galloway might have been helped by the weakening of the large Kingdom of the Isles. After the death of its king, Guðrøðr Crovan, King of the Isles, the Isles faced a lot of chaos and family conflicts. However, by the early 1100s, Guðrøðr Crovan's youngest son, Óláfr, was put back in power by Henry I, King of England. This was part of England's plan to increase its influence in the Irish Sea area.

Fergus's English Connections

There's a lot of evidence suggesting Fergus married a daughter of Henry I of England. Many believe this was Elizabeth Fitzroy. For example, records show that all three of Fergus's children—Uhtred, Gilla Brigte, and Affraic—were related to the English royal family. Uhtred was even called a cousin of Henry I's grandson, Henry II, King of England. While Gilla Brigte isn't directly called a relative, his son was considered a kinsman of Henry II's son, John, King of England. For Affraic, a writer named Robert de Torigni noted that her son, Guðrøðr Óláfsson, King of Dublin and the Isles, was related to Henry II through Henry II's mother, Matilda, who was one of Henry I's daughters.

Henry I had many children born outside of marriage. Although we don't know the name of Fergus's wife, she was likely one of these daughters. Henry I used these marriages to form alliances with leaders on the edges of his Anglo-Norman kingdom. Uhtred was born around 1123/1124 at the latest. Affraic was likely born by 1122, as her son was old enough to pay homage to the Norwegian king in 1153. These birth dates suggest Fergus's marriage happened when England was strengthening its power in the northwest and around the Irish Sea. For the English, an alliance with Fergus would have secured a good relationship with the ruler of an important part of their western border. Henry I also married another daughter, Sybilla, to Alexander I, King of Scotland, around the time Alexander became king. Fergus's marriage, therefore, shows his high status in Galloway and the level of political independence he had as its ruler. Both marriages show Henry I's goal of extending English power north of the Solway Firth.

David I and Scotland's Growing Power

The early 1100s saw the rise of David, Alexander's younger brother. David's strong ties with England likely helped him gain a large part of southern Scotland from Alexander. Around 1113, David married Maud de Senlis, a wealthy English widow. Through her, he gained control of a large territory known as the Honour of Huntingdon. As the middle of the century approached, the balance of power in the northern Anglo-Norman region began to shift towards David. In 1120, Henry I's only legitimate son died in a shipwreck. Henry I then moved a powerful lord, Ranulf le Meschin, from Carlisle to a new lordship.

When Alexander died in 1124, David became king. David then gave the lands of Annandale to Robert de Brus. This showed Scotland's intention to control the region and claim Cumbria. Fergus's marriage to Henry I's daughter, which happened around this time, might have been planned with these changes in mind. If so, the marriage could have been a way to balance the power shift caused by David's rise. With Ranulf gone from the north, Henry I brought in new lords. One of these was Robert de Brus, a Norman who had received lands from the English Crown. It's possible Robert de Brus was placed in Annandale by Henry I, or by Henry I and David working together, to secure the border between England and Scotland. Fergus's rise around this time might also have played a part in the settlement of Annandale.

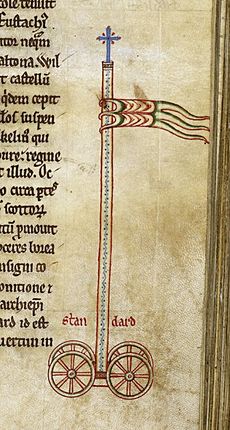

Henry I himself was married to David's older sister, Edith, which created a close bond with the Scottish royal family. As long as Henry I lived, relations between him and David were peaceful. However, when Henry I died in 1135, the peace broke. His nephew, Stephen of Blois, took the English throne. Before the end of that year, the Scots invaded and took Carlisle and Cumberland, but peace was soon restored. Relations broke down again in 1137, and the Scots invaded again, taking Northumberland and pushing towards York. English writers of the time, Richard Hexham and Ailred, specifically mentioned the Gallovidian soldiers for their terrible actions during David's campaign. In 1138, disaster struck the Scots at the Battle of the Standard, where David's forces were completely defeated by the English near Northallerton.

Although Gallovidians clearly fought in David's campaigns, there's no direct proof that Fergus was involved until after the fighting stopped. Fergus's appearance in a 1136 record might relate to Galloway's involvement. If Fergus's wife was indeed Henry I's daughter, Fergus had a stake in the English succession crisis. His wife would have been a half-sister to Matilda, whom Henry I wanted to be his successor, and who was Stephen's opponent. Richard Hexham recorded that one of the hostages given to the English after the peace treaty was the son of an earl named Fergus. Since there was no Scottish earl with that name, it might have been Fergus of Galloway himself. After this, there are no more records of Fergus's involvement in Anglo-Scottish affairs.

Fergus and the Church

Around 1128, the Diocese of Whithorn was brought back to life after three centuries without a bishop. We know this from a papal order in December 1128 and the oath of the new bishop, Gilla Aldan, to the Archbishop of York. It's not clear who was behind this revival. King David I was known for his church activities, so he might have been responsible. However, David's power in Galloway was uncertain. As for Fergus, there's no definite proof he controlled the lordship at this time or that he established the church area himself.

Gilla Aldan was likely from Galloway, unlike David's usual preference for English or Norman clergy. Also, Gilla Aldan promised obedience to the Archbishop of York, whom David was trying to keep out of Scottish church matters. This suggests Gilla Aldan was not a Scottish appointment. If Fergus was responsible for Whithorn's revival, it would have helped his royal ambitions. Gaining church independence could have been part of securing political independence. Gilla Aldan's successor was Christian, who became bishop in 1154.

Fergus and his family were very generous supporters of the church, working with different religious orders like the Augustinians, Benedictines, Cistercians, and Premonstratensians. Records show that Fergus gave lands to the Augustinian abbey of Holyrood. A later list of properties belonging to the Knights Hospitaller also shows that Fergus had given them lands. This further suggests Fergus's connection with the English Crown.

A record from the abbey of Newhouse states that Fergus founded a Premonstratensian monastery at Whithorn. Both he and Bishop Christian are said to have founded a monastery there. Christian was bishop from 1154 to 1186, and Fergus was lord until 1160. This suggests the priory of Whithorn was founded between 1154 and 1160. According to other records, this monastery was changed into a Premonstratensian house by Christian around 1177. These sources suggest Fergus started an Augustinian house at Whithorn, and Christian later re-founded it as a Premonstratensian one. Changing religious orders was not uncommon back then.

Either Fergus or David—or both—might have founded the abbey of Dundrennan, a Cistercian monastery located within Fergus's lands. Some historians say David founded it alone, but others don't mention it among David's known foundations. The fact that a Cistercian monk was very critical of Galloway and its people might suggest Fergus wasn't the only founder. David's own strong ties with the Cistercians could mean the monastery was founded through cooperation between David and Fergus.

Dundrennan Abbey seems to have been founded around 1142. This was when David's power was growing in the southwest. This date also means Máel Máedoc was in the region around that time, hinting at his possible involvement. If Fergus and David helped fund the abbey, the fact that Cistercians from Rievaulx came to settle there suggests it might have been a way to make up for the terrible actions of Gallovidian soldiers at the Battle of the Standard four years earlier. Also, the Archbishop of York had led the English resistance, meaning Fergus had fought against his own spiritual leader and likely faced church consequences. The Cistercians believed both Fergus and David were responsible for not stopping the atrocities during the campaign.

Another religious house possibly founded by Fergus was the abbey of Soulseat, a Premonstratensian monastery near Stranraer. However, this monastery seems to be the same as the "Viride Stagnum" mentioned in an old text, which suggests it started as a Cistercian house founded by Máel Máedoc himself. If Máel Máedoc and Fergus met at Cruggleton, Fergus might have given him the land to build a monastery at Soulseat. If Máel Máedoc did found a Cistercian house there, it was clearly changed to a Premonstratensian monastery soon after, with Fergus's support. The church of Cruggleton, near the castle, might also have been built by Fergus.

Some later medieval texts claim Fergus founded the priory of St Mary's Isle, but older records don't support these stories. A document from after Fergus's death confirms he gave the house to the abbey of Holyrood. Another document shows that the priory of St Mary's Isle might have existed during the time of Fergus's grandson, Roland fitz Uhtred, Lord of Galloway, though the first recorded leader of the priory appears in the 1200s. So, Fergus's direct links to this house are uncertain. Although some said Fergus founded the abbey of Tongland, his great-grandson, Alan fitz Roland, Lord of Galloway, seems to have founded it in the 1200s. Fergus might have been wrongly credited to make the monastery seem older and more important.

The reasons behind Fergus's support for the church are not entirely clear. He might have been copying or competing with the Scottish kings, who also supported many churches. His family connections with the rulers of England and the Isles might also have influenced his interest in church matters. Meeting important church leaders like Máel Máedoc and Ailred could have inspired his generosity.

Also, bringing Augustinians and Premonstratensians to Galloway might have been part of a plan to strengthen the newly re-established church area. Building churches and monasteries, like castles, was often a way for medieval rulers to show their power and importance. This could explain Fergus's church activities. His religious foundations might show his attempts to assert his authority in the region. While founding a bishopric seems to have been a way for Fergus to strengthen his independence from the Scots, his strong support for new religious orders might have been a way to make his claim to royal power seem more legitimate.

Troubles in the Isles

Alliance with Óláfr Guðrøðarson

Early in his time as lord, Fergus formed a strong connection with the Isles. His daughter Affraic married Óláfr, who was the reigning King of the Isles. We don't know the exact date of their marriage, but their son's trip to Norway in 1152 suggests the marriage happened in the 1130s or 1140s. This alliance between Óláfr and Fergus gave Óláfr's family valuable connections to the English Crown, which was one of the most powerful kingdoms in Europe. For Fergus, this marriage tied Galloway more closely to a neighboring kingdom that had previously launched an invasion. The alliance with Óláfr also gave Fergus the protection of one of Britain's strongest fleets and a valuable ally outside of Scotland's influence.

One reason Fergus might not have been involved in Anglo-Scottish affairs later on could be due to events in the Isles. Although a 12th-century record, the Chronicle of Mann, describes Óláfr's reign as peaceful, it's more likely he skillfully managed a difficult political situation. For Fergus, the capture of the Dublin kingship in 1142 by an Islesman might have threatened Óláfr's power and the future of Fergus's grandson. By the mid-1100s, Óláfr's kingdom might have been struggling, as shown by the attacks on mainland Scotland by Óláfr's bishop. The chronicle suggests Óláfr was worried about who would rule next. It states that his son, Guðrøðr, traveled to the court of Ingi Haraldsson, King of Norway, in 1152. There, Guðrøðr paid respect to the Norwegian king and likely secured his right to inherit the Isles.

The next year, 1153, was a turning point for the Kingdom of the Isles, with the deaths of both David I and Óláfr. Óláfr was killed by three of his exiled brother's sons, who were based in Dublin. These men then divided the Isle of Man among themselves. Once in control, the chronicle says they attacked Fergus to protect themselves from forces loyal to the rightful heir. Although the invasion of Galloway was pushed back with heavy losses, the chronicle records that when these relatives returned to Man, they killed and expelled all Gallovidians they could find. This harsh reaction clearly shows an attempt to remove any local groups supporting Affraic and her son. Within months of his father's death, Guðrøðr got his revenge. With military help from Norway, Guðrøðr defeated his three relatives and successfully became king.

The Rise of Somairle mac Gilla Brigte

In the mid-1100s, Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, King of Tír nEógain, pushed his claim to be the High King of Ireland. In 1154, Muirchertach's forces met those of the elderly Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht, in a major sea battle. According to a 17th-century record, Muirchertach's naval forces were mercenaries from Galloway, Arran, Kintyre, Man, and "the territories of Scotland." This suggests that Guðrøðr, Fergus, and perhaps Somairle, provided ships to Muirchertach. Although Toirrdelbach's forces won a narrow victory, his northern naval power was severely weakened. Muirchertach soon marched on Dublin, gained control over the Dubliners, and effectively became High King of Ireland.

The defeat of forces from the Isles and Muirchertach's growing power in Dublin might have had serious effects on Guðrøðr's rule. In 1155 or 1156, Somairle and a relative of Ottar led a rebellion against Guðrøðr. They put forward Somairle's son, Dubgall, as a replacement for Guðrøðr. Late in 1156, Somairle and Guðrøðr fought and divided the Kingdom of the Isles between them. Two years later, Somairle drove Guðrøðr from the kingship and into exile.

It's unclear why Fergus didn't support his grandson against Somairle. The capture of Domnall mac Máel Coluim at Whithorn in 1156, as recorded by the Chronicle of Holyrood, might be related to Fergus. Domnall seems to have been a son of Máel Coluim mac Alasdair, who claimed the Scottish throne and was related to Somairle. After David I's death in 1153, Somairle and Máel Coluim had rebelled against the new king, Malcolm, but without much success. Domnall's later capture in western Galloway could mean that these claimants tried to establish a power base there. However, the chronicle doesn't mention any conflict in Galloway, and Whithorn was a religious center, not a military one. This might suggest Domnall was in the region under less violent circumstances. If so, Fergus might have initially allied with Domnall. But then, pressure from his own sons might have forced him to abandon Domnall's cause. The fact that Domnall's capture happened before Somairle's rebellion could mean that once Somairle's plans against Guðrøðr became clear, the Gallovidians handed over Somairle's relative to the Scots.

Galloway Under Scottish Rule

There is evidence that Fergus struggled to keep control of his lands during this decade. Such problems might have prevented him from helping his grandson in the Isles. Similar to Guðrøðr, the failure of Muirchertach's mercenary fleet might have weakened Fergus's own authority. The chaos in Galloway is shown by a text called Vita Ailredi, which reveals that the region was full of family conflicts during this time.

In 1160, Malcolm IV returned to Scotland after months of fighting for the English. After successfully dealing with several unhappy nobles in Perth, he launched three military expeditions into Galloway. The reasons for these invasions are not clear, but Fergus submitted to the Scots before the end of the year. According to one record, once the Scots defeated the Gallovidians, they forced Fergus to retire to the abbey of Holyrood. He also had to give his son, Uhtred, as a hostage to the king. Other records confirm Fergus's retirement to the monastery and his gift of lands to the abbey.

It's possible Fergus himself caused Malcolm's reaction by raiding lands between the rivers Urr and Nith. The Chronicle of Holyrood describes Malcolm's opponents in Galloway as "allied enemies" and doesn't mention Fergus's sons, suggesting Fergus had other supporters. In fact, Malcolm might have faced an alliance between Fergus and Somairle. Evidence for this could be a royal document that mentions a formal agreement between Somairle and Malcolm that Christmas. Also, several churches near Kirkcudbright were once connected to Iona, an old church center that Somairle tried to revive. This might suggest some agreement between the two rulers. If Somairle and Fergus were allies, Fergus's fall and the Scottish advance into the Solway region might have finally forced Somairle to make peace with the Scots. Another possibility is that Somairle supported Malcolm in defeating Fergus. There's also reason to suspect that Ferteth, Earl of Strathearn, had some connection to Fergus. Ferteth was a prominent unhappy noble who confronted Malcolm in 1160. His father had played a leading role in the Battle of the Standard, and Ferteth himself was married to a woman whose name suggests she was from Galloway. The family conflicts mentioned in Vita Ailredi could mean Fergus's sons helped overthrow him, or at least did little to stop it.

Fergus's Death and What Happened Next

Fergus did not live long after retiring. He died on May 12, 1161, as recorded by the Chronicle of Holyrood. Records show that he was much more powerful than his sons during his lifetime. Uhtred witnessed only three documents, and Gilla Brigte none at all. Gilla Brigte's apparent exclusion from important matters might explain the later hostility between the brothers and the difficulties Fergus faced with them late in his life. After Fergus's death, his lands seem to have been divided between his sons. Although there's no specific evidence for Gilla Brigte's share, later records show Uhtred held lands in the lower Dee valley, likely centered around Kirkcudbright. Since this area seems to have been the core of Fergus's original holdings, it might mean Uhtred was the senior successor. It's possible Uhtred received the lands east of the river Cree, while Gilla Brigte received everything west of it.

After Malcolm's defeat of Fergus, the Scottish Crown worked to bring Galloway more fully into the Scottish kingdom. Uhtred seems to have been given the territory between the rivers Nith and Urr. Gilla Brigte might have married a daughter or sister of Donnchad II, Earl of Fife, who was Scotland's most important Gaelic noble. Scottish authority entered Galloway through the appointment of royal officials. Scottish power might have also been projected into Galloway by a royal castle at Dumfries. Royal documents from after Fergus's fall show that, from Scotland's point of view, the Lordship of Galloway had become part of the Kingdom of Scotland and was under the rule of Malcolm himself.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |