Scotland in the Late Middle Ages facts for kids

Scotland in the Late Middle Ages was a time of big changes, from 1286 (when King Alexander III died) to 1513 (when King James IV died). During this period, Scotland fought hard to stay independent from England. Heroes like William Wallace and Robert the Bruce helped secure Scotland's freedom.

In the 15th century, under the Stewart Dynasty, Scotland's kings gained more power. They took back most of the land that had been lost, making Scotland's borders much like they are today. However, Scotland's old friendship with France, called the Auld Alliance, led to a terrible defeat at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. King James IV died in this battle, leading to a time of trouble for Scotland.

Scotland's economy grew slowly. The population, which was almost a million in the mid-1300s, dropped by half after the Black Death arrived. Different ways of life developed in the lowlands and highlands. Gaelic was spoken mostly in the north, while Middle Scots was common in the south. Middle Scots became the language of the rulers and government. Religion also changed, with new groups of friars becoming popular, especially in towns.

By the end of this period, Scotland had embraced many ideas from the European Renaissance in art, buildings, and literature. It also developed a good education system. This era is seen as a time when a clear Scottish identity formed. However, it also showed big differences between the country's regions, which would be important later during the Reformation.

Contents

- Scotland's Fight for Freedom (1286–1371)

- The Stewart Kings (1371–1513)

- Scotland's Land and People

- Economy: How People Lived and Worked

- Society: How People Lived Together

- Government: How Scotland Was Ruled

- Warfare: Armies and Navies

- Religion: The Church and Beliefs

- Culture: Education, Art, and Language

- National Identity: Becoming Scottish

Scotland's Fight for Freedom (1286–1371)

Choosing a New King: John Balliol

When King Alexander III died in 1286, and his granddaughter Margaret died in 1290, there were 14 people who wanted to be king. To avoid a civil war, Scottish leaders asked Edward I of England to decide. Edward agreed, but first, he made them admit that Scotland was under his rule. He then chose John Balliol, who became King John I in 1292.

Edward I used this power to weaken King John and Scotland's independence. In 1295, King John made an alliance with France, starting the Auld Alliance. In 1296, Edward invaded Scotland and removed King John from power.

The next year, William Wallace and Andrew Murray led a fight against the English. Together, they defeated an English army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. Murray died from his wounds, and Wallace became the Guardian of Scotland for a short time. Edward I then came to Scotland himself and defeated Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk. Wallace escaped but later was captured by the English in 1305 and executed.

Robert the Bruce Becomes King

After Wallace, John Comyn and Robert the Bruce (grandson of an earlier claimant) became joint guardians. In 1306, Bruce was involved in Comyn's murder. Less than two months later, Bruce was crowned King Robert I at Scone. However, Edward's forces quickly took over the country.

Despite being excommunicated by the Pope, Bruce's support grew. By 1314, with help from nobles like Sir James Douglas, only two castles remained under English control. Edward I had died, and his son Edward II brought an army north. But Robert I's forces defeated them at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, securing Scotland's freedom.

In 1320, Scottish nobles sent a letter to the Pope, called the Declaration of Arbroath. This letter helped convince the Pope to recognize Scotland's independence. It's also seen as a key document in forming Scotland's national identity. Robert's forces also raided northern England, leading to the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton in 1328. This treaty officially recognized Scotland as an independent kingdom and Bruce as its king.

King David II's Reign

Robert I died in 1329, leaving his five-year-old son, David II, as king. During David's childhood, Scotland was ruled by guardians. England invaded again in 1332, trying to put Edward Balliol, John Balliol's son, on the Scottish throne. This started the Second War of Independence.

Even though the English won some battles, they couldn't keep Balliol on the throne because of strong Scottish resistance. Edward III lost interest when the Hundred Years' War with France began. David returned from France in 1341. In 1346, he invaded England to help France but was captured at the Battle of Neville's Cross. He remained a prisoner for 11 years.

David was released in 1357 for a large ransom. He struggled to pay it, leading to secret talks with England about an English king taking the Scottish throne. David died in 1371 without having children, ending the Bruce family's rule.

The Stewart Kings (1371–1513)

Robert II, Robert III, and James I

After David II's death, Robert Stewart became King Robert II in 1371, starting the Stewart (later Stuart) line of kings. His son, John, later King Robert III, took over the government when his father was older.

In 1406, Robert III sent his younger son, James, to France for safety. But the English captured James on the way, and he became a prisoner for 18 years. After Robert III died, Scotland was ruled by regents (people who govern for a young king), first by Robert's brother and then by his nephew.

When James I finally returned in 1424, he was 32 and determined to take control. He punished those who had gained power in his absence, even executing some of the Albany Stewarts. James tried to take back the Roxburgh fortress from the English in 1436 but failed. He was murdered in 1437 by unhappy nobles.

King James II

James I's seven-year-old son became King James II. During his childhood, powerful families like the Douglases, Crichtons, and Livingstons struggled for control. A plot to weaken the Douglas family led to the "Black Dinner" in 1440, where young William Douglas and his brother were killed.

In 1449, James II was declared old enough to rule. He began a long fight against the powerful Douglas family, eventually leading to the murder of the 8th Earl of Douglas in 1452. James slowly won over the Douglases' allies and finally defeated their forces in 1455.

James II became an active king, traveling the country to deliver justice. He had big plans to take Orkney, Shetland, and the Isle of Man, but these didn't happen. In 1460, he successfully took Roxburgh from the English, but he was killed by an exploding cannon during the siege.

King James III

James II's son, around nine or ten years old, became King James III. His mother, Mary of Guelders, ruled as regent until her death three years later. The Boyd family gained power, but they became unpopular. In 1469, the king took control and executed members of the Boyd family.

James III tried to make peace with England, even arranging for his son, the future James IV, to marry an English princess. This was very unpopular in Scotland. He also had conflicts with his brothers, one of whom died suspiciously.

By 1480, war with England started again. James was even imprisoned by his own subjects. Although he regained power, he upset many nobles by staying in Edinburgh, changing the money, and continuing to seek an English alliance. In 1488, he faced an army of unhappy nobles, who fought in the name of his son. James was defeated at the Battle of Sauchieburn and killed.

King James IV

James IV became king at 15 and quickly proved to be a strong ruler. His reign is often seen as a golden age for Scottish culture, influenced by the European Renaissance. He traveled the country to ensure justice was done.

James IV also brought the powerful Lordship of the Isles under royal control. He took over the lands of the last Lord of the Isles in 1493 and launched naval campaigns to defeat his rivals.

For a while, he supported an English pretender to the throne and briefly invaded England in 1496. However, he later made peace with England, signing the Treaty of Perpetual Peace in 1502 and marrying Henry VII's daughter, Margaret Tudor. This marriage set the stage for the future Union of the Crowns.

But in 1512, the old alliance with France was renewed. When England joined a league against France in 1511, James IV was caught in the middle. He declared war on England and led a large army south in 1513. After capturing Norham Castle, his army was decisively defeated at the Battle of Flodden. The King, many nobles, and many soldiers were killed. Scotland's government was once again left to regents for the infant James V.

Scotland's Land and People

Geography: Highlands and Lowlands

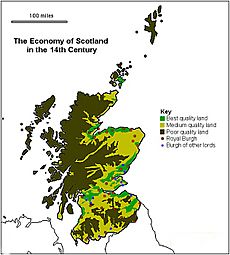

Scotland's geography is defined by its two main areas: the Highlands and Islands in the north and west, and the lowlands in the south and east. The Highlands are rugged and mountainous, while the lowlands have more fertile land. The Central Lowlands, about 50 miles wide, had the best farmland and communication, supporting most of the towns and government.

The Highlands and Southern Uplands were harder to govern and less productive. This rugged land protected Scotland from English invasions. However, it also made it difficult for Scottish kings to control these areas, leading to local conflicts.

By the end of this period, Scotland's borders were mostly like they are today. The Isle of Man came under English control. Scotland slowly regained land lost to England, especially when England was busy with the Wars of the Roses. In 1468, Scotland gained the Orkney Islands and Shetland Islands when James III married Margaret of Denmark. However, Berwick-upon-Tweed, an important border town, fell to the English for good in 1482.

Population Changes

It's hard to know exactly how many people lived in medieval Scotland. It's thought that the population was almost a million before the Black Death arrived in 1349. After the plague, the population may have dropped to as low as half a million by the early 1500s.

Compared to later times, the population was spread out more evenly across the country. About half the people lived north of the River Tay. Around ten percent lived in the fifty towns (burghs) that existed then, mostly in the east and south. The largest town, Edinburgh, probably had over 10,000 people by the end of this period.

Economy: How People Lived and Worked

Scotland has much less good farmland than England. So, farming on the edges of good land and fishing were very important. Travel was difficult, so most communities relied on what they produced locally.

Most farming was done in small settlements called farmtouns or bailes. A few families would farm an area together, dividing the land into strips called run rigs. This land included both wet and dry areas to help with different weather. Farmers used heavy wooden plows pulled by oxen. They also had to provide oxen for their lord's land and grind their grain at the lord's mill. The rural economy boomed in the 1200s but suffered a big drop in income after the Black Death, slowly recovering in the 1400s.

Towns and Trade

Most of Scotland's towns (burghs) were on the east coast, like Aberdeen, Perth, and Edinburgh. These towns grew wealthy from trade with Europe. In the southwest, Glasgow began to grow. Between 1450 and 1516, many smaller towns were created. These mostly served as local markets and centers for crafts, not international trade.

Wool was a major export early in the period. However, a sheep disease and market collapse in Europe caused wool exports to decline significantly. Unlike England, Scotland didn't develop large-scale cloth production.

Crafts and Industry

Scotland had few developed crafts during this time. By the late 1400s, there was a small iron casting industry that made cannons, and some silver and gold work. The most important exports were raw materials like wool, animal hides, salt, fish, and coal. Scotland often lacked wood, iron, and grain.

Exports of hides and salmon did better than wool, even with Europe's economic problems after the plague. The demand for luxury goods from Europe led to a shortage of silver and gold. This, along with royal money problems, caused the value of Scottish money to drop several times.

Society: How People Lived Together

In late medieval Scotland, family connections were very important. In the south, families often shared a surname, showing their common (sometimes made-up) ancestor. Unlike in England, women kept their original surnames after marriage. Marriages were meant to create friendships between families.

Clans in the Highlands

The combination of family ties and feudal duties led to the clan system in the Highlands. In the Middle Ages, not all clan members shared the same name, and most ordinary members were not directly related to the clan head. The clan head was usually the strongest male in the main family branch, later becoming the eldest son of the previous chief.

Leading families formed the fine, who advised the chief and led in war. Below them were the daoine usisle or tacksmen, who managed clan lands and collected rents. There were also buannachann, a military group who defended clan lands. Most clan followers were tenants who worked for the clan heads and sometimes served as soldiers.

Social Ranks

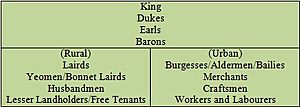

Scottish society had different ranks, similar to England. Below the king were a few dukes and earls, who were the highest nobles. Below them were the barons and, from the 1440s, the lords of Parliament, who had the right to attend the government assembly. There were about 40 to 60 of these nobles. Some nobles who served the king might also become knights.

Below the nobles were the lairds, similar to English gentlemen. Most worked for the greater nobles. Serfdom (where people were tied to the land) ended in Scotland in the 1300s, but landlords still had much control over their tenants.

Below the lords and lairds were groups like yeomen (sometimes called "bonnet lairds"), who owned significant land. Below them were husbandmen, smaller landholders and free tenants who made up most of the working population.

In towns, wealthy merchants were at the top, often holding local government positions. Below them were craftsmen and workers, who were the majority of the town population.

Social Challenges

Historians note conflicts in towns between wealthy merchants and craftsmen. Merchants tried to protect their trade and power, while craftsmen wanted more influence and control over their work. In the 1400s, laws were passed that strengthened the merchants' political power.

In rural areas, there wasn't much widespread unrest like in France or England. This might be because there weren't big changes in farming that would cause resentment. Instead, tenants often supported their landlords in conflicts, and landlords helped their tenants in return.

Highland and border areas were known for feuds (long-running disputes between families). However, some historians now see feuds as a way to settle arguments quickly, by forcing families to talk, pay compensation, and find solutions.

Government: How Scotland Was Ruled

The king was at the center of Scotland's government. The country's unity and independence from England helped make the king's position very important. However, the king's power was not always unchallenged, especially from powerful local lords. Scotland also faced many times when the king was a child, leading to regents ruling the country.

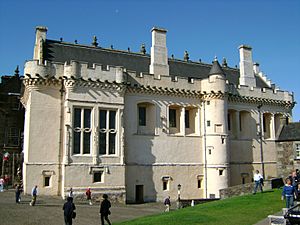

Scotland was a relatively poor kingdom, and there wasn't a regular tax system. This limited the size of the central government. The Scottish court often moved between royal castles, like Perth and Stirling. Edinburgh only slowly became the main capital under James III, which was unpopular with some. Like other European monarchies, the Scottish court in the 1400s adopted the style of the Burgundian court, focusing on grand ceremonies and art to show its power.

The King's Council

After the king, the most important government body was the Privy Council. This group of the king's closest advisors had both law-making and judicial powers. It was a small group, usually with fewer than 10 members. During times when the king was a child, Parliament would sometimes choose council members to limit the regent's power.

By the late 1400s, the council worked almost full-time and was crucial for royal justice. While powerful nobles were technically members, they rarely attended. Most active members were educated clergy (church officials) who worked as administrators and lawyers. Later, more educated laymen (non-clergy) joined the council, often becoming judges or gaining land.

Parliament's Role

Parliament was another important part of government. By the late 1200s, it had grown from the King's Council into a body with political and judicial roles. By the early 1300s, knights and town representatives (burgh commissioners) joined the bishops and earls to form the "Three Estates". Parliament met in various towns across Scotland.

Parliament had significant power, including approving taxes. It also influenced justice, foreign policy, war, and other laws. From the 1450s, much of Parliament's work was done by a committee called the 'Lords of the Articles', who drafted laws for the full assembly to approve.

Parliament met almost every year in the 1400s, more often than England's Parliament. It sometimes criticized the king's policies, especially during James III's unpopular reign. However, after James IV's successes, Parliament met less often. It might have declined if not for James IV's death in 1513 and another long period of a child king.

Local Government

At the local level, government combined traditional lordships (areas ruled by powerful families) with royal offices. Until the 1400s, major lordships remained strong. The Stewart family gained control of many earldoms. When they became kings, and after some internal conflicts, the monarchy gained control over most of the "provincial" earldoms and lordships by the 1460s.

In the lowlands, the king could now govern through sheriffs and other appointed officials, rather than relying on semi-independent lords. In the highlands, James II created new earldoms for his favorites, the Campbells and Gordons. These acted as a defense against the powerful Lordship of the Isles ruled by the Macdonalds. James IV largely solved the Macdonald problem by taking their lands and titles in 1493.

Scottish Armies

Scottish armies in the late Middle Ages were made up of family groups, community levies, and feudal troops. "Common service" meant all able-bodied freemen aged 16 to 60 could be called to fight. Feudal obligations meant knights provided troops for 40 days. Later, kings used money contracts to hire more professional soldiers, like men-at-arms and archers.

These armies had many poorly armored foot soldiers, often armed with long spears (12–14 feet). They formed large, tight defensive groups called shiltrons, which were good against mounted knights, as seen at Bannockburn. However, they were vulnerable to arrows and artillery. Later, attempts were made to use even longer pikes, but this wasn't very successful until just before the Flodden campaign.

Scotland had fewer archers and men-at-arms than England. Scottish archers became popular mercenaries in French armies to counter English archers. Scottish men-at-arms often fought on foot with the infantry.

Artillery: Cannons and Guns

Scottish kings, like those in France and England, tried to build up their artillery (cannons). James I used cannons in a siege in 1436. James II had a royal gunner and received cannons from Europe, including the giant Mons Meg, which still exists today. James II's love for cannons cost him his life when one exploded.

James IV brought experts from France, Germany, and the Netherlands and set up a cannon foundry in 1511. Edinburgh Castle had a place where visitors could see cannons being made. This gave Scotland a powerful artillery force, allowing James IV to quickly capture Norham Castle in the Flodden campaign. However, the 18 heavy cannons needed 400 oxen to pull them, slowing the army and proving less effective than the English guns at Flodden.

After gaining independence, Robert I began building a Scottish navy, mostly on the west coast. By the end of his reign, he had at least one royal warship. In the late 1300s, naval warfare with England was mostly done by hired merchant ships and privateers.

James I took more interest in naval power. He set up a shipbuilding yard at Leith in 1424. Royal ships were built for trade and war. James III also used his two warships, the Flower and the King's Carvel, for help in his struggles with nobles.

James IV greatly expanded the navy. He built a new harbor at Newhaven in 1504 and a dockyard at Airth. He acquired 38 ships, including the Margaret and the huge Great Michael. Launched in 1511, the Great Michael was 240 feet long, weighed 1,000 tons, and had 24 cannons, making it the largest ship in Europe at the time.

Scottish ships had success against pirates and helped the king in the islands. In the Flodden campaign, the fleet had 16 large and 10 smaller ships. After a raid in Ireland, it joined the French fleet but had little impact on the war. After the disaster at Flodden, the Great Michael and other ships were sold to the French, and the royal navy declined.

Religion: The Church and Beliefs

The Church in Scotland

Since 1192, the Catholic Church in Scotland had a direct relationship with the Pope, separate from England. Scotland didn't have archbishops until 1472, when St Andrews became the first, followed by Glasgow in 1492.

Religion had political importance. Robert I carried a holy relic into battle at Bannockburn. James IV used pilgrimages to show royal authority. There were efforts to make Scottish church services different from English ones.

During the Papal Schism of 1378, when there were multiple Popes, the Scottish king gained control over important church appointments. This allowed kings to place their relatives and supporters in key church positions, which led to accusations of corruption. Despite this, relations between the Scottish king and the Pope were generally good.

Religious Practices

Historians used to say the late medieval Scottish church was corrupt, but new research shows it met people's spiritual needs. Monasteries declined, with fewer monks. However, in towns, new groups of mendicant friars became popular in the late 1400s. They focused on preaching and helping people.

Most towns had only one parish church. But as the idea of Purgatory became more important, the number of chapels, priests, and masses for the dead grew rapidly. The number of altars dedicated to saints also increased dramatically. New devotions to Jesus and the Virgin Mary also arrived in Scotland in the 1400s.

In the 1400s, many clerics held two or more church positions because there were not enough clergy, especially after the Black Death. This meant parish clergy were often less educated. Heresy, like Lollardry, reached Scotland in the early 1400s, but it remained a small movement.

Culture: Education, Art, and Language

Education and Learning

In medieval Scotland, education was mostly controlled by the Church and aimed at training clergy. In the later medieval period, more schools appeared, and more lay people (non-clergy) got an education. This included private lessons for noble and wealthy town families, song schools at churches, and more grammar schools in growing towns. These schools were mostly for boys, but by the late 1400s, Edinburgh also had schools for girls.

The Education Act 1496 even said that all sons of important landowners should go to grammar school. This led to more people being able to read and write, especially among wealthy men.

Before the 1400s, Scots who wanted to go to university had to travel to England or Europe. But this changed with the founding of the University of St Andrews in 1413, the University of Glasgow in 1451, and the University of Aberdeen in 1495. These universities were first for training clergy but were increasingly used by laymen, who began to take over administrative jobs in government and law. Scottish scholars still traveled to Europe for higher degrees, bringing new ideas like humanism back to Scotland.

Art and Buildings

Scotland is famous for its castles, many built in the late medieval era. Unlike England, where wealthy people started building more comfortable houses, Scottish castles continued to be built for defense. These developed into the Scottish Baronial style, with unique features like corbelled turrets and crow-stepped gables.

The ceilings of these houses were often painted with bright colors and designs from European pattern books. The grandest royal palaces, like Linlithgow, Holyrood, Falkland, and Stirling Castle, combined traditional Scottish styles with European (especially French and Dutch) architecture.

Parish churches in Scotland were often simpler than in England, many being just oblong buildings without towers. In the Highlands, they were even simpler, sometimes looking like houses. However, some churches were built in a grander Gothic style, like Glasgow Cathedral and Melrose Abbey. Church interiors were often highly decorated before the Reformation. The carvings at Rosslyn Chapel (mid-1400s) are considered some of the finest Gothic art.

There isn't much information about Scottish artists from this time. Most impressive art came from artists brought in from Europe, especially the Netherlands, which was a center for painting. Examples include a lamp in Perth, altarpieces for Edinburgh churches, and illustrated books.

Language and Literature

During this period, the Scots language became the main language of the government and the upper class. It also became linked with Scottish national identity. Middle Scots came from Old English, with words from Gaelic and French. It became a distinct dialect from the late 1300s. By the 1400s, it was the language of government documents. As a result, Gaelic, once common north of the Tay, began to decline.

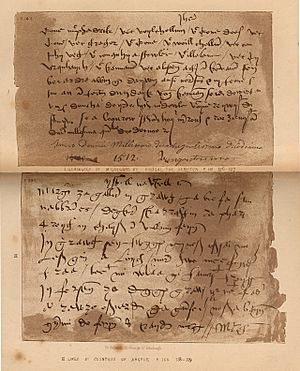

Gaelic was the language of the bardic tradition, where poets and storytellers passed down culture, history, and medicine through generations. They often played the harp. While the bardic tradition was influenced by European trends, it also produced important written works like the Book of the Dean of Lismore in the early 1500s. However, by the 1400s, lowland writers began to see Gaelic as a less important, rural language, creating a cultural divide.

Scots became the language of national literature. The first major text is John Barbour's Brus (1375), an epic poem about Robert I's fight for independence. It was very popular and Barbour is called the father of Scots poetry. Later works like Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland and The Wallace blended history with heroic stories.

Many important Scots writers, called makars, were connected to the royal court, including King James I himself. Many were also educated at universities and linked to the Church. Before printing came to Scotland, writers like Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, and Gavin Douglas led a golden age of Scottish poetry.

Scots prose also began to develop in the late 1400s. Early works include The Meroure of Wyssdome (1490). There were also Scots translations of French chivalry books. A landmark work was Gavin Douglas's translation of Virgil's Aeneid, called the Eneados, finished in 1513. It was the first complete translation of a major classical text into an English-based language.

Music and Sounds

Bards in Scotland were musicians, poets, storytellers, and historians. They often played the harp and were found in Scottish courts throughout the medieval period. Scottish church music was increasingly influenced by European styles.

James I, who was a poet and composer during his captivity in England, may have brought English and European musicians and styles back to Scotland. In the late 1400s, Scottish musicians trained in the Netherlands brought new organ playing techniques home. In 1501, James IV rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle, making it a center for Scottish church music.

National Identity: Becoming Scottish

The late Middle Ages is often seen as the time when Scottish national identity was formed. This happened partly because of English attempts to take over Scotland. English invasions created a strong sense of unity and dislike for England, which shaped Scottish foreign policy for a long time.

The Declaration of Arbroath stated Scotland's ancient independence from England, arguing that the king's role was to defend the Scottish community. This document is seen as the first "nationalist theory of sovereignty."

The adoption of Middle Scots by the upper class helped build a shared sense of national culture. However, the fact that Gaelic was still spoken in the Highlands created a cultural divide. Scottish national literature from this period used legends and history to promote the king and nationalism, helping to create a national identity among the elite. Epic poems like the Brus and Wallace told stories of a united fight against the English.

The origin myth of the Scots, written down by John of Fordun, traced their beginnings to a Greek prince and an Egyptian wife, allowing them to claim superiority over the English.

The national flag, the saltire (St. Andrew's Cross), became a common symbol during this time. It first appeared in the late 1200s. In 1385, the Scottish Parliament ordered soldiers to wear a white St. Andrew's Cross for identification. The blue background for the cross is thought to date from the 1400s. The earliest image of the St. Andrew's Cross as a flag is from around 1503.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |