Pytheas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pytheas of Massalia

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | c. 350 BC Massalia

|

| Nationality | Greek |

| Citizenship | Massaliote |

| Known for | Earliest Greek voyage to Britain, the Baltic, and the Arctic Circle for which there is a record, author of Periplus. |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geography, exploration, navigation |

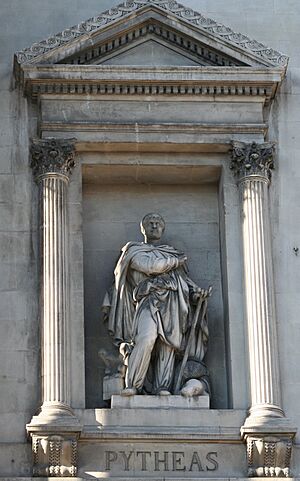

Pytheas of Massalia was a brave Greek explorer, geographer, and astronomer. He was born around 350 BC in Massalia (which is now Marseille, France). Around 325 BC, Pytheas made an amazing journey to Northern Europe.

His original travel stories are lost, but other ancient writers wrote about them. Pytheas was the first known Greek to visit and describe Britain, the Arctic Circle, and the icy seas. He also wrote about the Celtic and Germanic tribes he met. Pytheas was even the first person to describe the midnight sun, where the sun stays visible all night during summer. He also figured out that the Moon causes the tides.

Contents

How We Know About Pytheas

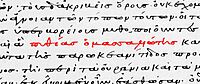

Pytheas wrote about his travels in a book that has not survived. We only know about his journey because later writers quoted or talked about his work. The most important ancient authors who mentioned Pytheas include Strabo (who wrote Geographica), Diodorus of Sicily (who wrote a world history), and Pliny (who wrote Natural History).

These writers lived hundreds of years after Pytheas. They often used his information, even if they sometimes doubted him. Pytheas's book was likely called "On the Ocean." It was probably a type of travel log, like a ship's diary.

When Pytheas Sailed

Historians believe Pytheas's voyage happened around 320 BC. This is because his discoveries were not mentioned by Aristotle, a famous philosopher. However, Pytheas's work was discussed by Dicaearchus, who was Aristotle's student. This helps us guess the time of his journey.

Starting the Journey

Pytheas was the first known sailor from the Mediterranean Sea to reach the British Isles. The city of Carthage had blocked the Strait of Gibraltar to ships from other nations. This made it hard for Pytheas to sail out.

Some historians think he might have traveled by land to a river like the Loire or Garonne in France. Others believe he sailed very close to the coast or at night to avoid the Carthaginian ships. Another idea is that Massalia, Pytheas's home city, had a good relationship with Carthage at that time. This might have allowed him to pass through the strait freely.

Pytheas's journey likely started by sailing north along the coast of Portugal. He mentioned places like Sagres Point and Cádiz, which suggests he passed through the Strait of Gibraltar.

Voyage to Britain

Sailing Around Britain

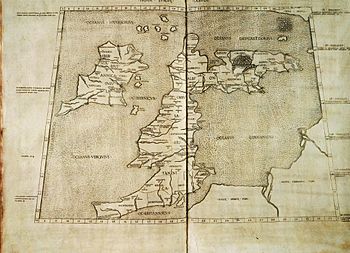

Pytheas said he "traveled over the whole of Britain that was accessible." He estimated Britain's perimeter to be more than 40,000 stadia. This is a very large number, about 4,545 miles. Some ancient writers, like Strabo, thought this number was too high.

However, Pytheas might have measured his journey in "days' sail." Later writers might have converted these days into stadia using a standard rate. If Pytheas stopped often to gather information, this would make the journey seem longer in terms of days. Modern calculations suggest a perimeter of about 2,375 miles, which is more realistic.

Pytheas likely spent time on land to gather information about the stars and talk to the local people. This would explain why his journey took longer.

Naming and Describing the British People

Pytheas was the first to write down the name "Britain." He called it Bretannikē. This name is similar to words used in modern Celtic languages. The word "British" might have come from a word meaning "people of forms" or "pictures." This could refer to their practice of tattooing or painting their bodies. The Romans later called some of these people "Picts," which means "painted."

Pytheas probably interacted more with people who spoke P-Celtic languages, like those in modern Wales or Brittany. He did not seem to distinguish between different groups of people on the island.

Based on Pytheas's accounts, Diodorus Siculus described Britain as a cold place with frosts. He said the people lived in thatched cottages and stored their grain underground. They were described as simple and content. They had many kings and princes who lived peacefully. Their soldiers fought using chariots, similar to how Greeks fought in the Trojan War.

The Three Corners of Britain

Pytheas described Britain as having three main corners. One was Kantion (Kent), which was about 11 miles from the mainland of Europe. Another was Belerion, which is likely Cornwall. The third point was Orkas, probably the main island of the Orkney Islands in the north.

The Tin Trade

The people in Cornwall were skilled at making tin ingots. They mined the tin, melted it, and shaped it into pieces. Then, they transported it to an island called Ictis by wagon when the tide was low. Merchants bought the tin there and carried it on horses for 30 days to the Rhône river, where it was shipped to the sea. Diodorus said the people of Cornwall were polite and welcoming to strangers because they traded with foreign merchants.

Scotland

Pytheas was the first to mention Scotland in writing. He called the northern tip of Britain "Orcas," which is where the name for the Orkney Islands comes from.

Discovering Thule

Strabo wrote that Pytheas claimed to have explored "the whole northern region of Europe as far as the ends of the world." Strabo did not believe him. Pytheas called this far northern land Thoulē (now spelled Thule). It was the most northerly of the British Isles.

Pytheas said that in Thule, the summer sun never set. This means it was near the Arctic Circle. Other ancient writers did not mention Thule, which suggests Pytheas was the first explorer to reach it and tell others about it.

Thule was described as an island six days' sail north of Britain, near a "frozen sea." Pliny added that there were no nights at midsummer. Pytheas might have sailed from an island called Berrice, possibly Lewis in the Hebrides. If so, he might have reached the coast of Norway, explaining how he missed the Skagerrak strait. This route also suggests he might not have sailed all the way around Britain.

Pytheas described the people of Thule as living on millet, herbs, fruits, and roots. They also made a drink from grain and honey, possibly mead. He said they pounded their grain in large barns because there was not enough sunshine for outdoor threshing. This sounds like an agricultural country.

Encountering Drift Ice

After Thule, Pytheas mentioned a "frozen ocean" that was one day's sail away. This "solidified sea" was probably drift ice. He described it as a mixture of land, sea, and air, like a "marine lung." This term might refer to jellyfish or pancake ice, which are circular pieces of ice floating in the water.

This ice would have stopped his journey further north. Pytheas's observations of drift ice are well-known in sailing history. He described the edge of the ice where sea, slush, and ice mix, often surrounded by fog.

Discovering the Baltic Sea

Pytheas also described the area beyond the Rhine river, reaching as far as Scythia. This means he likely described the Germanic coast of the Baltic Sea. He probably sailed along this coast, possibly reaching the Vistula river.

Pliny wrote that Pytheas spoke of a large estuary called Metuonis, where a German tribe lived. From there, it was a day's sail to the Isle of Abalus. Pytheas said that amber was carried to this island by currents in spring. The people there used amber as fuel and sold it.

Pytheas also described a very large island called Basilia, which was three days' sail from the Scythian coast. This island was also known for amber.

Voyage to the Don River

Polybius wrote that after returning from the north, Pytheas traveled along the entire coast of Europe from Cádiz to the Tanais river. Some historians think this might have been a second journey. It is interesting that he reached the border of Scythia in the north and then sailed around Europe to reach the southern side of Scythia on the Black Sea. He might have hoped to sail all the way around Europe.

Measuring Latitude

Using the Sun's Height

Pytheas was able to figure out how far north or south he was (his latitude) by measuring the height of the sun. He used a tool called a gnōmōn, which was a vertical rod. By measuring the length of the shadow the rod cast at noon on the longest day of the year, he could calculate the sun's angle.

He found that Massalia and Byzantium were on the same latitude. His measurements were quite accurate for his time, showing he was a skilled observer.

Using the North Star

Another way Pytheas measured latitude was by looking at the celestial pole (the point in the sky directly above the Earth's North Pole). The higher the pole appeared in the sky, the further north he was.

Today, we use Polaris (the North Star) to find the North celestial pole. But in Pytheas's time, due to the slow wobble of the Earth, Polaris was not exactly at the pole. Pytheas noted that the pole was an empty space, with three stars forming a corner around it.

Pytheas wanted to find the Arctic Circle and explore the "frigid zone" beyond it. He knew the Arctic Circle was where the sun would not set on the longest day of the year. He would have stopped often during his journey to make these measurements and talk to the local people. The people he met, both Celts and Germans, seemed to help him, suggesting his expedition was seen as scientific.

Understanding the Tides

Pytheas was the first to connect the tides to the Moon. He noticed that in Britain, the tides were much higher than in the Mediterranean Sea. He said that the high tides were caused by the "filling of the moon" and the low tides by its "lessening." This might mean he linked the tides to the phases of the moon, like full moons and new moons, which is partly correct for spring tides. Even though his explanation was not perfect, it was a big step in understanding the tides.

Pytheas's Influence

Pytheas was a very important source of information about Northern Europe for many centuries. Many later writers, like Dicaearchus, Timaeus, and Eratosthenes, used his original writings.

Some ancient writers, like Strabo, doubted Pytheas. Strabo thought Pytheas might have made up parts of his journey because he was a private person and might not have had enough money for such a big trip. However, some historians think Pytheas's journey might have been funded by the merchants of Massalia, who wanted to find new trade routes in the north.

Strabo also said Pytheas was wrong about some known places. For example, he claimed Pytheas said Kent was several days' sail from Celtica, even though it is visible across the channel. But Pytheas might have placed Celtica further south, making the distance more accurate from his perspective.

Despite the doubts, Pytheas was a daring explorer and a keen observer. Many questions about his voyage remain unanswered, but his work continues to inspire people. He is even featured in modern books and poems, like Charles Olson's Maximus Poems and Poul Anderson's science fiction novel The Boat of a Million Years. The Stone Stories trilogy by Mandy Haggith also revolves around Pytheas's journeys.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Piteas para niños

In Spanish: Piteas para niños

- Britain (place name)

- Cruthin

- Euthymenes

- Mining in Cornwall

- Prydain

- Scythia

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |