Mining in Cornwall and Devon facts for kids

Mining in Cornwall and Devon, located in the southwest of Britain, started way back in the early Bronze Age, around 2150 BC. The main metals dug out were tin and later copper. Even after other metals became too expensive to mine, some tin mining continued. However, it finally stopped in the late 20th century. In 2021, exciting news came out: a new mine began digging for battery-grade lithium carbonate. This was more than 20 years after the last tin mine, South Crofty in Cornwall, closed in 1998.

Historically, people mined tin, copper, and other metals like arsenic, silver, and zinc in Cornwall and Devon. There's still tin underground in Cornwall, and there's been talk of reopening the South Crofty tin mine. Also, work has started to reopen the Hemerdon tungsten and tin mine in southwest Devon. Because mines and quarries were so important for the economy, scientists studied the rocks. They found about forty different minerals unique to Cornwall. Digging for igneous and metamorphic rocks was also a big industry. In the 20th century, digging for kaolin (china clay) became very important for the economy.

Contents

How Cornwall's Geology Created Minerals

When hot granite pushed into the surrounding sedimentary rocks, it caused big changes and created many minerals. This made Cornwall one of Europe's most important mining areas until the early 1900s. People believe that tin ore (cassiterite) was mined in Cornwall as early as the Bronze Age. Over time, many other metals, like lead and zinc, were also mined. Alquifou, a lead ore found in Cornwall, was used by potters to give pottery a green glaze. Because of both nature and human mining, there's a lot of heavy metal pollution in the county. Arsenic levels change depending on the rock types and how much they were mined in the 1800s and 1900s. Although arsenic was used in paint, weedkillers, and bug sprays, it was usually a leftover from processing tin and copper. Arsenic and other unwanted heavy metals were often left in waste piles near the mines.

A Journey Through Mining History

Cornwall and Devon supplied most of the United Kingdom's tin, copper, and arsenic until the 20th century. At first, tin was found as alluvial deposits (loose bits) of cassiterite in riverbeds. Later, people started mining tin underground. The first specially designed tin mines appeared as early as the 1500s. Tin deposits were also found in rock sticking out of cliffs.

Ancient Times: Stone Age to Bronze Age

Tin is one of the first metals people used in Britain. Early metalworkers discovered that adding a small amount of tin (5–20%) to melted copper made bronze. Bronze is much harder than copper. The oldest tin-bronze was made in Turkey around 3500 BC. But in Britain, people started using tin resources before 2000 BC. A busy tin trade then grew with the civilisations around the Mediterranean Sea. Because tin was so important for making bronze weapons, southwest Britain became connected to the Mediterranean economy very early on. Later, tin was also used to make pewter.

Mining in Cornwall has been happening since the early Bronze Age Britain, around 2000 BC.

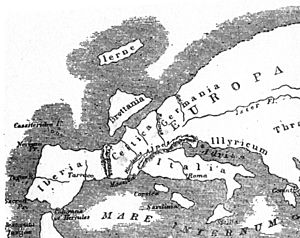

People used to think that Phoenician metal traders from the eastern Mediterranean visited Cornwall. However, this idea changed in the 20th century. Experts now say there's no direct archaeological proof that Phoenician or Carthaginian traders came as far north as Britain. Britain is one of the places suggested for the Cassiterides, which means "Tin Islands," first mentioned by the ancient historian Herodotus.

The tin found in the Nebra Sky Disc, an ancient artifact from 1600 BC, was found to be from Cornwall.

At first, people probably collected tin from loose deposits in stream gravels. But later, they started mining underground. Shallow cuts were then used to get the ore out.

Growing Trade Routes

As the demand for bronze grew in the Middle East, local tin ore (cassiterite) supplies ran out. So, people searched for new supplies all over the known world, including Britain. The Phoenicians seemed to control the tin trade and kept their sources secret. The Greeks knew tin came from the Cassiterides, the "tin islands," but their exact location is still debated. By 500 BC, the historian Hecataeus knew of islands beyond Gaul where tin was found. Pytheas of Massalia traveled to Britain around 325 BC and found a busy tin trade, according to later reports of his journey. Posidonius mentioned the tin trade with Britain around 90 BC. But Strabo, around 18 AD, didn't list tin as one of Britain's exports. This was probably because Rome was getting its tin from Hispania (Spain) at that time.

William Camden, in his book Britannia (1607), said the Cassiterides were the Scilly Isles. He was the first to popularize the idea that the Phoenicians traded with Britain. However, there's no proof of tin mining on the Scilly Isles, except for small explorations. Timothy Champion thought it was more likely that the Phoenicians' trade with Britain was indirect. It was probably controlled by the Veneti people of Brittany (France). Champion, talking about Diodorus Siculus's comments on the tin trade, says that "Diodorus never actually says that the Phoenicians sailed to Cornwall. In fact, he says quite the opposite: the production of Cornish tin was in the hands of the natives of Cornwall, and its transport to the Mediterranean was organised by local merchants, by sea and then over land through France, well outside Phoenician control."

There is scientific evidence that tin blocks found off the coast of Haifa, Israel, came from Cornwall.

Diodorus Siculus's Story

In his book Bibliotheca historica, written in the 1st century BC, Diodorus Siculus described old tin mining in Britain. He wrote: "The people who live on the British headland of Belerion are more civilized because they meet many foreigners. These people prepare the tin, which they dig out of the ground with great care. Then, they mix the metal with some earth, melt it, and make it pure. After that, they shape it into blocks and carry it to a nearby island called Ictis. At low tide, the ground between the mainland and the island becomes dry, and large amounts of tin are brought over in carts."

Pliny, another ancient writer, quoted Timaeus of Taormina about "insulam Mictim" (the island of Mictim). Several places have been suggested for "Ictin" or "Ictis," which means "tin port," including St. Michael's Mount. But after digging, Barry Cunliffe suggested it was Mount Batten near Plymouth. A shipwreck with tin blocks was found at the mouth of the River Erme nearby. This might show trade along this coast during the Bronze Age, though it's hard to date the site. Strabo reported that British tin was shipped to Marseille.

The Legend of Joseph of Arimathea

Ding Dong mine, said to be one of Cornwall's oldest mines in the parish of Gulval, has a local legend. It says that Joseph of Arimathea, a tin trader, visited the mine and brought a young Jesus to speak to the miners. However, there is no real proof for this story.

Iron Age Discoveries

There are few ancient tin mining remains in Cornwall or Devon. This is probably because later mining destroyed the older sites. However, shallow cuts used for digging out ore can still be seen in places like Challacombe Down, Dartmoor. A few stone hammers, like those in the Zennor Wayside Museum, have been found. It's likely that most mining was done with shovels, antler picks, and wooden wedges. At Dean Moor on Dartmoor, a site from 1400–900 BC, diggers found a tin ore pebble and tin slag (waste). Rocks were used to crush the ore, and crushing stones were found at Crift Farm. Tin slag has also been found on the floors of Bronze Age houses, for example, at Trevisker. Tin slag was found at Caerloges with an ancient dagger.

In the Iron Age, bronze was still used for decorations, but not for tools and weapons. So, tin mining seems to have continued. A tin block from Castle Dore is probably from the Iron Age.

Roman and Post-Roman Times

Some say that the Romans invaded Britain because of its tin resources. However, they already controlled mines in Spain and Brittany in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Later, tin production in Spain decreased, probably due to raids. Production in Britain increased in the 3rd century, used for coins and a lot in making pewter. Cornwall and West Devon were less Romanized than other parts of Britain. Tin mining might have been run by local people, with the Roman government buying the tin. A possible official stamp was found on the Carnington tin block. Several tin blocks have been found in Roman sites, like 42 found in a shipwreck at Bigbury Bay in 1991–92.

A site in the Erme Valley, Devon, shows that sediment built up in late Roman and Post-Roman times because of tin mining on Dartmoor. There was a lot of mining activity between the 4th and 7th centuries. Tin slag at Week Ford in Devon has been dated to 570–890 AD.

St Piran (the patron saint of tin miners) is said to have arrived at Perranporth from Ireland around 420 AD.

Medieval and Modern Mining Eras

The Middle Ages

The Domesday Book doesn't mention tin mining, possibly because the rights belonged to the King. In the early 1100s, Dartmoor produced most of Europe's tin, even more than Cornwall. The Pipe Roll of Henry II shows Dartmoor's yearly tin production was about 60 tons. In 1198, he agreed that "all the diggers and buyers of black tin, and all the smelters of tin, and traders of tin in the first smelting shall have the just and ancient customs and liberties established in Devon and Cornwall." This proves that mining had been going on for a long time. King John granted a charter in 1201, confirming the miners' rights. Records from the Erme Valley in Devon show tin waste building up between 1288 and 1389.

After power went to the Norman lord Robert, Count of Mortain, who owned the manor of Trematon, silver mining became a huge industry. This was especially true in the Tamar valley around Bere Ferrers in Devon. Started in 1292 by Edward I, skilled workers were first brought from Derbyshire and North Wales. Experts came from Germany, and money came from Italy. Profits from the King's silver mines led to the rise of the old Cornish Edgcumbe family at Cotehele and later Mount Edgcumbe.

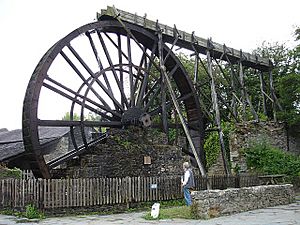

In 1305, King Edward I set up separate stannaries (tin mining districts) for Devon and Cornwall. Water was used to power stamps that crushed the ore, washing away the lighter waste. The mineral "black tin" was put into furnaces and layered with peat. The melted metal was poured into granite molds, making tin blocks. These were taken on pack horses to the stannary towns to be tested for purity. Usable deposits in Devon ran out, so Cornwall became the main tin producer. In 1337, Cornish tin production was 650 tons, but in 1335 it dropped to 250 tons because of the Black Death. By 1400, Cornish production rose to 800 tons. Devon's production was only 25% of Cornwall's in 1450–1470.

The tin works of Devon and Cornwall were so important that medieval kings set up stannary courts and stannary parliaments to make laws for Cornwall and parts of Devon. Until the mid-1500s, Devon produced about 25–40% of the tin that Cornwall did. But the total tin production from both areas during this time was quite small.

The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 started among Cornish tin miners. They were against Henry VII raising taxes to fight Scotland. They disliked this tax because it would cause financial hardship and it went against a special tax exemption for Cornwall. The rebels marched on London, gaining supporters, but were defeated at the Battle of Deptford Bridge.

Quarrying was not very important in medieval Cornwall. Stone for churches was rarely brought from outside the county; builders used whatever stone was nearby. For decorative parts like doorways and fonts, they used types of elvan (like Polyphant and Catacleuze). Granite was not quarried but collected from the moorlands and shaped on site. Quarrying of slate grew in north Cornwall in the later Middle Ages and became larger operations in early modern times.

Early Modern Mining

After the 1540s, Cornwall's production quickly increased, and Devon's production was only about 10–11% of Cornwall's. From the mid-1500s, the Devon stannaries brought very little money to the Crown, and they were pushed aside. The first Crockern Tor stannary parliament in Devon was held in 1494, and the last in 1748. At Combe Martin, several old silver mines are on the eastern ridge. You can still see tunnels and the remains of a wheelhouse used to lift ore. Some items in the Crown Jewels are made from Combe Martin silver.

A second tin boom happened around the 1500s when open-pit mining was used. German miners, who knew these techniques, were hired. In 1689, Thomas Epsley, a man from Somerset, found a way to blast the very hard granite rock using gunpowder with quill fuses. This changed hard rock mining forever. Six days of work with a pick could be done with one blast. There was a third boom in the 1700s when deep shafts were dug to get the ore.

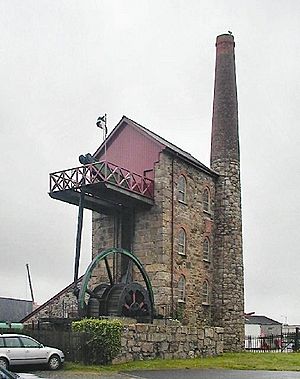

Later Modern Mining

In the 1800s, Cornish mining reached its peak. But then, competition from other countries lowered the price of copper and later tin. This made digging for Cornish ore unprofitable. The areas around Gwennap and St Day and on the coast near Porthtowan were among the richest mining areas in the world. At its busiest, the Cornish tin mining industry had about 600 steam engines working to pump water out of the mines. Many mines went under the sea and some were very deep. Investors put up money, hoping the mine would make a profit, but the results were very uncertain.

Caradon Hill had the most productive mine in east Cornwall. The South Caradon Copper Mine, 1 km southwest of the Caradon Hill transmitting station, was the largest copper mine in the UK in the mid-1800s. Other old copper and tin mines are scattered around the base of the hill. By the mid-1800s, Looe became a major port, one of Cornwall's largest. It exported local tin, arsenic, and granite, and had busy fishing and boatbuilding industries. At Callington, arsenic was found with copper ores. It was processed by crushing and condensing. The poisonous dust made the work very dangerous. Many safety steps were taken, but workers often died in middle age. Kit Hill Country Park is full of mining history. Metals dug out included tin, silver, copper, and tungsten. The main mines were Kit Hill Summit Mines (which had a windmill near the current stack) (started around 1826; Kit Hill United closed in 1864); East Kit Hill Mine, worked from 1855 to 1909; Hingston Down mine (which worked west towards Kit Hill, may have started in the 1600s, it closed in 1885); and South Kit Hill Mine, worked from 1856 to 1884.

The last Cornish Stannary Parliament was held at Hingston Down in 1753. The Devon Stannary Parliament last met in 1748. The Stannary Courts of Devon and Cornwall were combined in 1855, and their powers were given to local authorities in 1896.

By the mid-to-late 1800s, Cornish mining was slowing down. Many Cornish miners moved to new mining areas overseas, where their skills were needed. These places included South Africa, Australia, and North America. Cornish miners became very important in the 1850s in the iron and copper districts of northern Michigan in the United States, as well as in many other mining areas. In the first six months of 1875, over 10,000 miners left Cornwall to find work abroad.

20th Century and Beyond

During the 1900s, different ores were briefly profitable, and mines reopened. But today, none remain. Dolcoath mine (Cornish for Old Ground), known as the 'Queen of Cornish Mines', was 3,500 feet (1,100 m) deep. For many years, it was the deepest mine in the world and one of the oldest before it closed in 1921. The last working tin mine in Europe was South Crofty, near Camborne, until it closed in March 1998. After an attempt to reopen it, it was abandoned. In September 2006, local news reported that South Crofty might reopen because tin prices had gone up. But the site was subject to a compulsory purchase order (October 2006). On the wall outside the gate, there's graffiti from 1999:

Cornish lads are fishermen and Cornish lads are miners too.

But when the fish and tin are gone, what are the Cornish boys to do?

(This is from the song 'Cornish Lads' by Roger Bryant.)

The collapse of the International Tin Council in 1986 marked the end for Cornish and Devonian tin mining. The most recent mine in Devon to produce tin ore was Hemerdon Mine near Plympton in the 1980s. The last Cornish tin mine, South Crofty, closed in 1998. The Hemerdon tungsten and tin mine in southwest Devon reopened as Drakelands Mine in 2015.

In 1992, Geevor mine was bought by Cornwall County Council to become a heritage museum, now run by Pendeen Community Heritage. Both Geevor Tin Mine and Morwellham Quay have been chosen as "anchor points" on the European Route of Industrial Heritage.

Digging for china clay (kaolin) is still very important. The larger operations are in the St Austell area. The amount of waste compared to kaolin is so huge that enormous white waste mounds were created. In the early years, their whiteness meant they could be seen from far away. The Eden Project was built on the site of an old china clay and tin quarry. Digging for slate and roadstone still happens on a smaller scale. It used to be a big industry and has been done in Cornwall since the Middle Ages. Several quarries were productive enough to need their own mineral railways. High-quality granite has been dug from many Cornish quarries like De Lank and Porthoustock. Some granite has been transported very long distances for building. There are also important quarries in Devon, like Meldon (a source of railway ballast) and granite quarries on Dartmoor like Merrivale.

In 2017, plans were reported to extract lithium from beneath Cornwall by Cornish Lithium, who signed agreements to develop potential deposits.

In April 2019, a British company, MetAmpère Limited, drilled six lithium exploration holes near St Austell. MetAmpère successfully extracted lithium from hard rock in a lab, leading to plans for 20 more drill holes. In 2021, a new mine began extracting battery-grade lithium carbonate.

Mining Accidents

In the metal mines of Cornwall, some serious accidents happened. At East Wheal Rose in 1846, 39 men died in a sudden flood. At Levant Mine in 1919, 31 were killed and many injured when a "man engine" (a machine to move miners) failed. Twelve men died at Wheal Agar in 1883 when a cage fell down a shaft. And seven men were killed at Dolcoath mine in 1893 when a large support structure collapsed.

Key Mining Areas

Cornwall

- Penwith

- St Just in Penwith and Zennor

- Camborne, Redruth and Illogan

- Gwennap and the Carnon Valley in west Cornwall

- Wendron area in Kerrier

- St Agnes and Porthtowan

- North Cornwall (a few mines but no tin)

- A large area between St Austell, Wadebridge, Bodmin and Callington in mid and east Cornwall

River Tamar

- Tamar Valley - copper, tin, lead, silver, and arsenic. See Morwellham Quay. In the 1800s, ores were traded internationally through Plymouth Dock.

Devon

- Lydford – an ancient Saxon town; the early medieval site of the most westerly silver mint and later a ceremonial parliament and prison for the Stannary Court for Dartmoor.

- Bere Ferrers – a unique silver (and lead) mine run by the Crown in medieval times.

- Combe Martin – lead/silver deposits.

- Exmoor and Brendon Hills – iron, lead, silver, copper.

- Dartmoor – ancient stannary towns include Tavistock, Ashburton, Chagford and later Plympton.

- West Devon

- Bampfylde Mine, North Molton

- Blackdown Hills – copper deposits.

Learning About Mining

The Royal Geological Society of Cornwall was founded in 1814 to study the geology of Cornwall. It is the second oldest geological society in the world. The Cornish Institute of Engineers was started by mechanical engineers and is active in mining.

Camborne School of Mines

Because metal mining was so important to Cornwall's economy, the Camborne School of Mines (CSM), founded in 1888, became the only special school for hard rock mining education in the UK. It still teaches mining and many other earth-related subjects (like engineering geology) important to Cornwall.

CSM is now part of the University of Exeter and has moved to the University's Tremough campus in Penryn. Despite this move, the School still uses "Camborne" in its name. CSM graduates work in the mining industry all over the world.

Mining Words and Symbols

Several Cornish mining words are still used in English mining terms. These include costean, gunnies, vug, kibbal, gossan, mundic and kieve.

Fish, tin, and copper are sometimes used as a symbol for Cornwall. They represent the three main traditional industries of Cornwall. Tin has a special place in Cornish culture. The Stannary Parliament and 'Cornish pennies' show how powerful the Cornish tin industry once was. Cornish tin is highly valued for jewelry, often featuring mine engines or Celtic designs.

The houses at Penair School are named after four famous tin mines. Some pubs are named after tin mining, like the Tinner's Arms in Zennor and the old Jolly Tinners pub in St Hilary. The pub sign at Zennor shows a tin miner working, a reminder of its history. The Jolly Tinners building at St Hilary was once used as the St Hilary Children's Home.

The Three Hares Symbol

The three hares is a circular symbol found in sacred sites from the Middle and Far East to churches in southwest England. In England, it's often called the "Tinners' Rabbits." It appears most often in churches in the West Country of England. The symbol is seen in carved wood, carved stone, window designs, and stained glass. In Southwest England, there are almost thirty examples of the Three Hares on 'roof bosses' (carved wooden knobs) on the ceilings of medieval churches in Devon, especially Dartmoor. A good example of a Three Hares roof boss is at Widecombe-in-the-Moor. Another great example is in the town of Tavistock, Dartmoor, on the edge of the moor.

"Tinners' Rabbits" is also the name of a dance that uses sticks and involves three, six, or nine dancers rotating.

World Heritage Site Status

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Old tin mine workings near Pendeen in Cornwall

|

|

| Location | Cornwall and West Devon, United Kingdom |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii)(iii)(iv) |

| Inscription | 2006 (30th Session) |

| Area | 19,719 ha (48,730 acres) |

In 1999, the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape was suggested to be added to the World Heritage list. On July 13, 2006, it was announced that the bid was successful! This World Heritage Site is special because it represents mining techniques that were used all over the world, even in Mexico and Peru. It includes a trail linking mining sites from Land's End in Cornwall, through Porthtowan and St Agnes, up through the county to the Tamar Valley. The Tamar Valley forms the border with Devon. There, the exporting port of Morwellham is being developed. It shows the scale of the mining operations, with the Eastern Gateway to the World Heritage Site located in the ancient stannary town of Tavistock, which was important during Devon's own 19th-century gold rush.

Heartlands, a £35 million project funded by the National Lottery, is a gateway to the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site. It opened to the public on April 20, 2012. This free visitor attraction had been planned for 14 years (since South Crofty mine closed in 1998).

In 2014, work was finished to preserve the famous New Cooks Kitchen Headframe at South Crofty tin mine. This cost about £650,000.

Important Mines

Hemerdon Mine

Hemerdon Mine, also known as the Drakelands Mine or Hemerdon Ball Mine, is an old tungsten and tin mine. It's about 11 km (7 miles) northeast of Plymouth, near Plympton, in Devon. It's north of the villages of Sparkwell and Hemerdon, and next to the large china clay pits near Lee Moor. The mine had been closed since 1944, except for a short trial in the 1980s. It holds one of the world's largest tungsten and tin deposits. It started producing again in 2015.

South Crofty Mine

In November 2007, it was announced that South Crofty mine, near Camborne, might start producing again in 2009. When it closed in 1998, it was Europe's last tin mine. Its owners, Baseresult Holdings Ltd, bought the mine in 2001. They created a new company, Western United Mines Limited (WUM), to run it. They said they would spend over £50 million to reopen the mine. The company claimed that rising tin prices gave the mine, first opened in the late 1500s, another 80 years of life. More than £3.5 million would be spent in the next seven months to continue developing the mine.

Crofty Developments, a partner of the new company, still had to settle a disagreement with the South West Regional Development Agency (RDA). The RDA wanted to buy over 30 acres (120,000 m2) of land around the site to use for recreation, housing, and industry. But Crofty Developments fought in the High Court to keep the site. The Cornish mining industry, which began in 2000 BC, reached its peak in the 1800s. At that time, thousands of workers were employed in up to 2,000 mines. The industry later collapsed when ores could be produced more cheaply abroad.

Mining Railways

Many railways were built to serve the mines, moving minerals and supplies. These were often called "mineral railways" because they were directly linked to mines.

Cornwall Minerals Railway

The Cornwall Minerals Railway opened in 1874. It connected harbors at Fowey and Newquay with mineral extraction sites in between, especially in the Bugle and St Dennis areas. This railway took over and extended several shorter existing mineral lines.

East Cornwall Mineral Railway

The ECMR connected copper mining areas around Kit Hill to a quay at Calstock on the Tamar River.

Hayle Railway

The Hayle Railway opened in 1837. It served engineering works and copper quays at Hayle and the copper mines of Redruth and Camborne.

Images for kids

See also

- Bal maidens, female ore dressers

- Beam engine

- Come, all ye jolly tinner boys

- Cornish emigration

- Cornish engine

- Cornish Foreshore Case

- Cornish Mines & Engines

- Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape, a World Heritage Site

- Dartmoor tin-mining

- Geology of Cornwall

- Hayle, center of copper smelting

- John Taylor, inventor of the Cornish rolls

- Kenneth Hamilton Jenkin, historian

- Knocker, said to inhabit the mines

- Lostwithiel Stannary Palace

- Mineral Tramway Trails

- Morwellham Quay, inland port

- Robert Hunt, mineralogist and statistician

- Tin sources and trade in ancient times

- Welcome Stranger (a notable nugget of gold found by two Cornish miners in Victoria, Australia)

- William Jory Henwood, mining geologist

- Williams family of Caerhays and Burncoose, mining entrepreneurs

- Scorrier House, seat of the Williams family