End of Roman rule in Britain facts for kids

The end of Roman rule in Britain was a big change. It was when Roman Britain became post-Roman Britain. Roman control didn't end all at once. It happened at different times and in different ways across Britain.

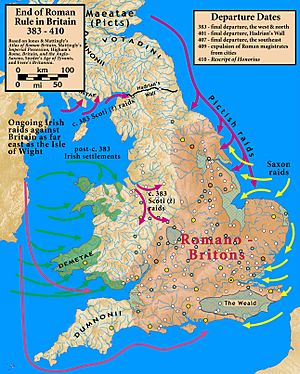

In 383, a general named Magnus Maximus took soldiers from northern and western Britain. He probably left local leaders in charge. Around 410, the people of Roman Britain kicked out the Roman officials. These officials worked for a general named Constantine III. He had taken the Roman army from Britain to Gaul (modern France). This was after many Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine River in 406. Britain was left open to attacks from invaders.

The Roman Emperor Honorius was asked for help. He sent a message called the Rescript of Honorius. It told the Roman cities in Britain to defend themselves. This meant he accepted that Britain would govern itself for a while. Honorius couldn't send help because he was fighting a huge war in Italy. The Visigoths led by Alaric were attacking, and Rome itself was under siege. No soldiers could be spared for far-off Britain.

Honorius likely thought he would get control back later. But by the mid-500s, a historian named Procopius knew that Rome had completely lost Britain.

Contents

Why Roman Rule Ended

By the early 400s, the Roman Empire was struggling. It couldn't defend itself from internal rebellions. It also faced threats from Germanic tribes expanding in Western Europe. This situation led to Britain becoming permanently separate from the Empire. After a time of local rule, the Anglo-Saxons arrived in southern England in the 440s.

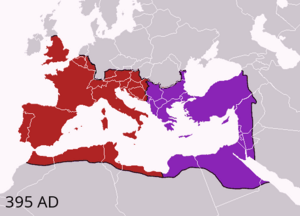

In the late 300s, the Empire was ruled by a powerful family. This family included Emperor Theodosius I. They kept political power within their family. They also made alliances by marrying into other powerful families. But they also fought among themselves. And they had to fight off people called "usurpers." Usurpers were people who tried to take over as emperor. These internal struggles used up a lot of the Empire's soldiers and resources. Thousands of soldiers were lost fighting people like Magnus Maximus.

The Roman Empire had a complicated relationship with Germanic tribes. Sometimes they were enemies, sometimes they worked together. But eventually, the tribes became too strong. By the early 400s, the Western Roman Empire's army had many Germanic soldiers. Romanized Germans also played a big role in Roman politics. Various tribes outside the Empire took advantage of Rome's weakness. They moved into Roman lands. This led to many successful migrations starting in 406.

The crossing of the Rhine River caused great fear in Britain. Britain was worried about being cut off from the Empire. The main route from Italy to the Channel coast was often raided. This crossing was much more than just another raid.

Key Events

383 to 388: Magnus Maximus's Rise

In 383, the Roman general in Britain, Magnus Maximus, decided to try to become emperor. He took his soldiers and crossed to Gaul (modern France). He killed the Western Roman Emperor Gratian. Maximus then ruled Gaul and Britain as a "sub-emperor" under Theodosius I.

The year 383 is the last time we have clear proof of a strong Roman presence in northern and western Britain. Some small outposts might have lasted into the 390s. These were mainly to stop attacks from groups like the Déisi from Ireland.

Coins from after 383 have been found near Hadrian's Wall. This suggests that soldiers might not have been completely removed from there. Or, if they were, they returned quickly after Maximus won in Gaul. A writer named Gildas, around 540 AD, said that Maximus took all the soldiers, governors, and young men from Britain. He said they never came back.

Raids by Saxons, Picts, and the Scoti from Ireland had been happening in the late 300s. But these attacks grew worse after 383. There were also large Irish settlements along the coasts of Wales. We don't know exactly how these happened. Maximus fought against the Picts and Scoti in Britain. Historians disagree if this was in 382 or 384.

Welsh legends say that before Maximus tried to become emperor, he changed how Britain was governed and defended. Figures like Coel Hen were supposedly put in charge to protect the island. But these stories were often made to support Welsh family histories. So, we should be careful about believing them completely.

In 388, Maximus led his army into Italy to try and become the main emperor. But he was defeated in battles in modern Croatia and Slovenia. Theodosius then had him executed.

389 to 406: Stilicho and More Raids

After Maximus's death, Britain was again ruled by Emperor Theodosius I. Then, a general named Eugenius tried to become emperor in the West. He was defeated by Theodosius in 394. When Theodosius died in 395, his 10-year-old son Honorius became Western Roman Emperor. But the real power was Stilicho. He was related to Theodosius and Honorius.

Britain was still being raided by the Scoti, Saxons, and Picts. Sometime between 396 and 398, Stilicho supposedly ordered a campaign against the Picts. This was likely a naval attack to stop their raids on Britain's east coast. He might have also fought the Scoti and Saxons. This was the last Roman military campaign in Britain that we have records of.

In 401 or 402, Stilicho faced wars with the Visigoths and Ostrogoths. He needed more soldiers. So, he took troops from Hadrian's Wall for the last time. The year 402 is the last time many Roman coins were found in Britain. This suggests that Stilicho either took the remaining soldiers, or the Empire couldn't pay them anymore. Meanwhile, the Picts, Saxons, and Scoti continued their raids. These attacks might have even increased. For example, in 405, Niall of the Nine Hostages is said to have raided along Britain's southern coast.

407 to 410: Britain Defends Itself

On the last day of December 406 (or maybe 405), tribes like the Alans, Vandals, and Suebi crossed the Rhine River. They caused widespread destruction.

The Romans couldn't stop them. The remaining Roman soldiers in Britain feared that these tribes would cross the English Channel next. So, they decided to ignore the Roman Empire's authority. This was probably easier because they hadn't been paid for a while. They wanted to choose a leader who would protect them. Their first two choices, Marcus and Gratian, didn't work out and were killed. Their third choice was a soldier named Constantine III.

In 407, Constantine took charge of the remaining troops in Britain. He led them across the Channel into Gaul. He gathered support there and tried to become Western Roman Emperor. Emperor Honorius's loyal forces in Italy were busy fighting the Visigoths. So, they couldn't quickly stop Constantine's rebellion. This gave Constantine a chance to expand his new empire to include Hispania (modern Spain and Portugal).

In 409, Constantine's control of his empire fell apart. Some of his soldiers were in Hispania. Others in Gaul turned against him. Germanic tribes living west of the Rhine rebelled against him. Those east of the river crossed into Gaul. Britain was now without any soldiers for protection. It had also suffered very bad Saxon raids in 408 and 409. The people in Britain were very worried about the situation in Gaul.

Perhaps feeling they had no hope from Constantine, the people of Roman Britain and some in Gaul expelled Constantine's officials. This happened in 409 or 410. A historian named Zosimus blamed Constantine directly. He said Constantine allowed the Saxons to raid. He said the Britons and Gauls were in such a bad state that they rebelled against the Roman Empire. They "rejected Roman law, went back to their own customs, and armed themselves to stay safe."

According to Zosimus, the British communities asked Emperor Honorius for help in 410 AD. Honorius's reply is called the Rescript of Honorius. It was written around 411. In it, Honorius told the British civitates (cities) to look after their own defense. His government was still fighting other usurpers in Gaul. And they were trying to deal with the Visigoths in Italy.

The first mention of this message is by Zosimus, a Byzantine scholar from the 500s. It's found in the middle of a discussion about southern Italy. No other mention of Britain is made. This has led some modern experts to suggest the message wasn't for Britain at all. They think it was for a region in Italy called Bruttium.

However, historian Christopher Snyder said that Honorius usually wrote to Roman officials. The fact that he wrote to the cities themselves suggests that the cities of Britain were now the highest Roman authority there.

When the Rescript was sent, Honorius was trapped in Ravenna by the Visigoths. He couldn't stop them from sacking Rome in 410. He certainly couldn't offer any help to Britain. As for Constantine III, he couldn't handle the politics of imperial Rome. By 411, his attempt to be emperor was over. He and his supporters were killed.

Different Ideas About What Happened

Historians have different ways of looking at these events. They might support a certain idea without changing the basic timeline.

The historian Theodor Mommsen said in 1885 that "It was not Britain that gave up Rome, but Rome that gave up Britain." He believed that Rome's needs and priorities were elsewhere. Many scholars still agree with this idea.

Michael Jones, in his 1998 book The End of Roman Britain, had the opposite view. He said that Britain left Rome. He argued that many generals from Britain tried to become emperor. He also said that poor Roman management caused the Romano-Britons to rebel. Some scholars, like J. B. Bury and Ralf Scharf, completely disagreed with the usual timeline. They argued that there is proof of Roman involvement in Britain even after 410.

Disputes About the Facts

Regarding the events of 409 and 410, when the Romano-Britons expelled Roman officials and asked Honorius for help, Michael Jones offered a different order of events. He suggested that the Britons first asked Rome for help. When no help came, they then expelled the Roman officials and took charge of their own affairs.

One idea in some modern histories is about the Rescript of Honorius. This idea says it refers to the cities of the Bruttii. These people lived in the "toe" of Italy, in modern Calabria. This idea is based on the thought that the historian Zosimus or a copyist made a mistake. They might have written Brettania (Britain) when they meant Brettia (Bruttium). Also, the part of the text with the message is mostly about events in northern Italy.

However, many criticisms exist for this idea. Some historians just use Zosimus's text as it was written. Others point out that the idea is just a guess. They also ask questions like, "Why would Honorius write to the cities of the Bruttii instead of his own governor there?" And, "Why would far-off southern Italy be in a passage about northern Italy, any more than far-off Britain?" This idea also goes against the account of Gildas. Gildas also wrote about this event and clearly said it was about Britain.

E. A. Thompson offered another idea in 1977. He suggested that a revolt of unhappy peasants, like the Bagaudae in Gaul, also happened in Britain. He thought that when these peasants revolted and expelled the Roman officials, the landowners then asked Rome for help. There is no direct text that says this. But it might be possible if we change the meaning of 'bagaudae' to fit. However, there are other simple explanations that already fit the situation. It's possible that some form of 'bagaudae' existed in Britain. But they might not have been directly involved in the events of 409 and 410.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |