Bruttians facts for kids

The Bruttians (also called Brettii) were an ancient people who lived in the southern part of Italy. Their land stretched from the borders of Lucania all the way to the Straits of Messina, which is the narrow sea passage near Sicily. This area is very similar to the modern-day region of Calabria.

The Bruttians originally lived in the mountains and hills of Calabria. They were the southernmost group of the Italic tribes, who were ancient peoples of Italy. They were related to the Samnites, another powerful Italic tribe.

The Bruttians are known for taking over ancient Greek cities, called poleis, in a region known as Magna Graecia (which means "Great Greece"). They were also brave fighters who often rebelled against the powerful Romans.

You can learn more about the Bruttians at the Museo dei Brettii e degli Enotri in Cosenza, Italy. This museum has lots of new information about them.

Contents

What Does "Bruttii" Mean?

The name Bruttii is very old. Ancient writers mention them as early as 446/445 BC. For example, Diodorus wrote that the Bruttians drove out the people of Sybaris, an ancient Greek city.

The oldest proof we have of the name Bruttii comes from a piece of pottery found in southern Campania. It has an inscription from the mid-6th century BC that says "Bruties esum," meaning "I am of Brutius."

The name Bruttii comes from ancient Indo-European languages. It's similar to an Illyrian word, brentos, which means "deer." The ancient Greeks called them Βρέττιοι (Bréttioi). Their coins also show the name ΒΡΕΤΤΙΩΝ, meaning "of the Brettioi." The historian Polybius called their land ἡ Βρεττιανὴ Χώρα, which probably means "the land of the Brettioi."

After 356 BC, when the Bruttians became independent, their name started to mean "rebels" or "runaway slaves" to the Lucanians and other ancient people. This was because of their social background.

Where Did the Bruttians Live?

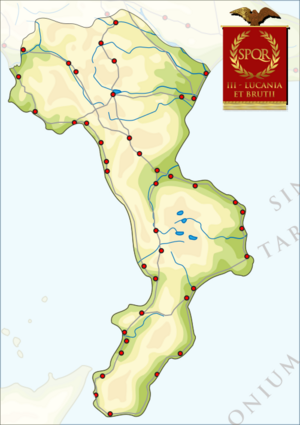

The land of the Bruttians covered almost all of what is now the province of Cosenza in Italy. It was bordered by the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west and the Sicilian Sea (which included the Gulf of Tarentum) to the south and east. This area is roughly the same as modern Calabria, though the name Calabria only came into use much later, during Byzantine times.

The Roman historian Livy called their territory Bruttii provincia, meaning "Bruttian province."

Later, the Roman emperor Augustus included the Bruttian land in the "Third Region" of Italy, along with Lucania. These two areas were often governed together until the Roman Empire fell.

A Brief History of the Bruttians

Who Were the First People There?

Before the Bruttians, the land was home to the Oenotrians, another Italic tribe. Their name means "wine-making people," which tells us something about their activities. The Conii and Morgetes were smaller groups within the Oenotrians.

While the Oenotrians lived there, the first Greek traders arrived. They loved the climate and how quickly their settlements grew. Soon, many Greek colonies were built along the coast.

The geographer Stephanus of Byzantium wrote in the 6th century AD that the Bruttians were mentioned as early as the 5th century BC. He specifically talked about bruttia pix, which was pitch (a sticky substance) from the Sila forests. These forests were very important to the Bruttians. They provided shelter for animals, wood for building, and pitch for waterproofing ships and containers. Pitch was also used in medicine and cosmetics.

How the Bruttians Rose to Power

In the 4th century BC, a big change happened. The Lucanians, another Oscan-speaking people, began moving south. They took control of the northern parts of Oenotria and then pushed into the Bruttian peninsula. They took over the inland areas and many Greek settlements. This likely happened after their big victory over the people of Thurii in 390 BC.

Ancient writers say the Bruttians became independent around 356 BC. This was when Dion of Syracuse led an expedition against Dionysius the Younger of Syracuse. The wars between Syracuse and the Greek cities in southern Italy made these cities weak. This helped the Bruttians rise to power.

Some ancient writers describe the Bruttians as a group of rebellious people. The historian Justin says they were led by 500 young men of Lucanian origin. These young men joined shepherds living in the forests, along with other local Italic tribes like the Ausones, Mamertines, and Sicels. Diodorus described many of these groups as runaway slaves and "experts in war." Because of their social background, the name Bruttii came to mean "rebels" or "runaway slaves."

The Bruttians spoke a form of Oscan. There were also some Illyrians who settled in the area earlier, adding to their culture.

Some recent ideas suggest that most Bruttians came from the local people who had lived there for a long time. These people had inscriptions in the Achaean alphabet and an ancient Italic language. So, the Bruttians might not have been just slaves or descendants of the Lucanians. Instead, they could have been Italic people from the Oenotrian background, going back to at least the 5th century BC.

Growing Stronger

Once they appeared in history, the Bruttians grew quickly. They expanded their territory, succeeding in both the south and north. They also impacted the Greek cities to the east and west. They soon became strong enough to challenge the Lucanians and kept their independence in the mountain regions. The Lucanians seemed to accept their independence easily.

The Bruttian tribes lived in many small villages, a few kilometers apart. They also had fortified towns where important people like warriors, leaders, and priests gathered to make decisions for the surrounding villages. They even minted their own money. Their society began to form, with warriors becoming a very important social class.

The Bruttians formed a league called the Confoederatio Bruttiorum. This was the peak of their expansion, culture, and economy. They made Consentia (modern-day Cosenza) their capital city. Other important cities included Pandosia, Aufugum (modern Montalto Uffugo), and Bisignano.

Archaeological findings show about sixty native centers in Calabria during the Hellenistic age, before the Romans took over. Fifteen of these centers were fortified.

Wars with Greek Cities

Less than 30 years after their first revolt, the Bruttians joined the Lucanians as allies. They attacked and took over the Greek cities of Hipponium, Terina, and Thurii. The people of Thurii asked for help from Alexander of Epirus, a king who came to Italy with his army. He fought for several years, conquering cities like Heraclea, Consentia, and Terina. But he eventually died in a battle against the Lucanians and Bruttians near Pandosia in 326 BC.

Next, the Bruttians fought against Agathocles of Syracuse. He attacked their coasts with his ships and took the city of Hipponium. He turned it into a strong fortress and naval base, forcing the Bruttians to agree to a difficult peace treaty. But they soon broke the treaty and got Hipponium back. This was probably when the Bruttian nation was at its strongest and most successful.

However, they soon faced an even stronger enemy: Rome. As early as 282 BC, the Bruttians joined the Lucanians and Samnites against Rome's growing power.

The Pyrrhic War

A few years later, the Bruttians sent soldiers to help Pyrrhus of Epirus, a Greek king who fought against Rome. But after Pyrrhus was defeated and left Italy in 275 BC, the Bruttians had to face the Romans alone. After many battles and victories by Roman generals, the Bruttians were finally defeated. They had to make peace by giving up half of the great Sila forest, which was very valuable for its pitch and timber.

After Pyrrhus's defeat, the Bruttian way of life changed. Their cities were called allies of Rome, but they were not allowed to make their own alliances or mint their own coins. The only advantage Rome gave them was keeping their traditional laws and leaders. This was only a formal independence, because Roman soldiers in their fortified cities made sure everything was done according to Roman interests.

In the decades before the Second Punic War, the Bruttian cities and farms became poorer. This was because of the destruction from the Pyrrhic War and the political problems affecting the Greek cities.

The Second Punic War

The Bruttians had never fully given up. When Hannibal, a famous Carthaginian general, invaded Italy in 218 BC, they saw a chance to regain their independence. After Hannibal's victory at the Battle of Cannae, the Bruttians became his allies. They recaptured Consentia and tried to become independent again.

The city of Rhegium (modern Reggio Calabria) remained loyal to Rome and resisted the Carthaginians throughout the war. In 215 BC, Hanno, one of Hannibal's commanders, retreated to Bruttium after a defeat. He was joined by new troops from Carthage. From then on, Bruttium became his base. He would launch attacks from there and retreat to its safety when he was defeated. The region's natural features made it a very strong military position.

After another Carthaginian general, Hasdrubal, was defeated and killed, Hannibal himself moved some of his forces into Bruttian territory. He continued to fight against the Roman generals there. In the final stages of the war (204-202 BC), many Bruttian cities surrendered to the Roman consul Gnaeus Servilius Caepio.

Hannibal stayed in this province for four years. His main headquarters were often near Crotona. A small town on the Gulf of Squillace was even called Castra Hannibalis (Hannibal's Camp), showing he used it as a permanent base. Meanwhile, the Romans avoided big battles but slowly gained ground by taking over towns and fortresses. Very few cities remained in Carthaginian hands when Hannibal was finally called back to Africa.

Becoming Roman

After Hannibal left for Africa, the Romans took steps to punish the Bruttians. The damage from so many wars also greatly affected Bruttium's wealth. The Bruttians lost their right to carry weapons. Many of them became slaves or were forced into lower-ranking jobs, serving Roman officials instead of being Roman soldiers. Rome took away Consentia's status as a city-state, broke up the Bruttian Confederation, and took almost all their land, turning it into public land. Their hill forts were abandoned or destroyed.

It took some time for the Bruttians to be completely controlled. For several years after the Second Punic War, a Roman praetor (a type of official) was sent with an army each year to watch over them. To make sure they stayed under control, Rome established three colonies of Roman veteran soldiers and their families in Bruttian territory. Two were for Roman citizens at Tempsa and Crotona, and a third, with Latin rights, was at Hipponium, which was renamed Vibo Valentia. A fourth colony was also settled at Thurii, right on their border. Some ancestors of the first Roman Emperor, Augustus, were among the settlers at Thurii.

In the late 2nd century BC, the Via Popilia road was built. This road became very important for Roman control, not just for military and political reasons, but also for trade. It connected the region and improved existing coastal routes.

The Bruttians became so completely Roman that they were rarely mentioned later, with only a few exceptions. Their country became a battlefield again during the revolt of Spartacus, a famous gladiator who led a slave rebellion. After his first defeats, Spartacus hid in the southernmost part of Bruttium. The Roman general Crassus tried to trap him by building trenches across the narrowest part of the land, from sea to sea. However, Spartacus broke through and continued the war in Lucania.

During the Roman Civil Wars, the coasts of Bruttium were repeatedly attacked by the fleets of Sextus Pompeius. There were also several battles between his fleets and those of Octavian (who later became Emperor Augustus). Octavian had set up his army and navy headquarters at Vibo. The ancient writer Strabo said that by his time, the entire province was in a state of decay.

Later Roman Empire

It was once thought that southern Italy, including Bruttium, became economically unimportant and declined even more in the last centuries of the Roman Empire.

However, between the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, many smaller farms struggled and were often sold to wealthy landowners. These rich owners could invest in their land, making it more productive and increasing their wealth. They expanded their luxurious villas, making them grander and more impressive. In Bruttium, more than 60% of the villas from the earlier Roman periods disappeared during this time. This trend continued into the 4th and 5th centuries, especially in the coastal areas.

But discoveries in the last 20 years, like the wealthy Roman Villa Palazzi di Casignana from the 4th century, show that the area actually had a long period of peace and security during the 3rd and 4th centuries. In fact, the region experienced an economic boom and a significant growth in its rural population. Many villas, farms, villages, churches, and rural areas have been found through surveys and aerial photos. Other luxurious villas were found nearby, such as at Marina di Gioiosa Ionica, Naniglio, Ardore, and Quote San Francesco.

Bruttium's good location in the Mediterranean and its strong land and sea connections were key reasons why rich Roman senators and local important people invested there in the 4th and 5th centuries. The Roman emperors also owned significant land in this area. Southern Italy was one of the last places, between the 5th and 6th centuries, to have large estates and economic growth linked to farming, raising animals, crafts, and trade. This was happening while the system was falling apart in other parts of Italy. However, the coastal areas were abandoned in the 5th century, probably due to pirate raids. This led to the development of safer towns in the hills inland, like Gerace.

By the 5th century, as the Western Roman Empire declined, the region of Brettiōn asked the Roman Emperor for help against pirate raids on the coast. For many years, this event was mistakenly recorded as happening in Britain, due to the similar-sounding names.

See Also

- List of ancient Italic peoples

- Bruttia gens

Sources

- William Smith, LLD, Ed., BRUTTII, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854) [1]

- Pier Giovanni Guzzo, Storia e cultura dei Brettii [2]

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |