History of the Faroe Islands facts for kids

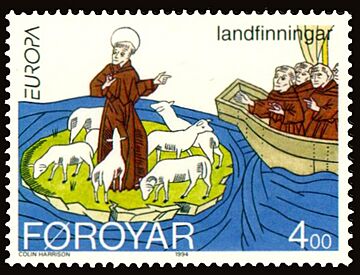

The Faroe Islands have a long and interesting history. Early details about the islands are not fully clear. Some believe that Brendan, an Irish monk, might have sailed past them in the 6th century. He described an 'Island of Sheep' and a 'Paradise of Birds'. This description fits the Faroes, which have many birds and sheep.

This also suggests that other sailors might have visited before him, bringing the sheep. Norsemen settled the Faroe Islands in the 9th or 10th century. The islands officially became Christian around the year 1000. They then became part of the Kingdom of Norway in 1035.

Norway ruled the islands until 1380. After that, the Faroes became part of the combined kingdom of Denmark–Norway. This happened under King Olaf II of Denmark.

In 1814, the Treaty of Kiel ended the Denmark–Norway kingdom. The Faroe Islands then stayed under Denmark's control as a county. During World War II, Nazi Germany occupied Denmark. To prevent a German takeover, the British occupied the Faroe Islands. This lasted until shortly after the war ended.

In 1946, the Faroes held an independence vote. Denmark did not officially recognize this vote. However, in 1948, the Faroe Islands gained more self-governance. This was through the Home Rule Act of the Faroe Islands.

Contents

Early Settlers and the Viking Age

There is some proof that people lived on the Faroe Islands before the Norse Viking settlers arrived. This was in the 9th century AD. Scientists found burnt grains of barley and peat ash. These were from two different time periods. The first was between the mid-4th and mid-6th centuries. The second was between the late-6th and late-8th centuries.

Researchers also found sheep DNA in lake sediments. This DNA was dated to around the year 500. Barley and sheep must have been brought to the islands by humans. It is unlikely that the Norse sailed near the Faroes much before the early 800s. So, the first settlers might have come from the British Isles. An archaeologist named Mike Church thinks these people could have been from Ireland, Scotland, or Scandinavia. Maybe even from all three places.

An old story from the 9th century tells of the Irish saint Brendan. It says he visited islands that sound like the Faroes in the 6th century. However, this description is not completely certain.

The earliest text that might describe the Faroe Islands was written by an Irish monk named Dicuil. This was around 825 AD. Dicuil wrote about islands in the far north. He said a trustworthy man told him he reached these islands after sailing for "two days and a summer night".

Dicuil wrote:

Many other islands lie in the northerly British Ocean. One reaches them from the northerly islands of Britain, by sailing directly for two days and two nights with a full sail in a favourable wind the whole time.... Most of these islands are small, they are separated by narrow channels, and for nearly a hundred years hermits lived there, coming from our land, Ireland, by boat. But just as these islands have been uninhabited from the beginning of the world, so now the Norwegian pirates have driven away the monks; but countless sheep and many different species of sea-fowl are to be found there...

The Norse settlement of the Faroe Islands is mentioned in the Færeyinga saga. The original book is now lost. Parts of the story are found in three other sagas. These are the Flateyjarbók, the Saga of Óláfr Tryggvason, and AM 62 fol. Like other sagas, it's not fully certain how historically accurate the Færeyinga saga is.

Both the Saga of Óláfr Tryggvason and the Flateyjarbók say that Grímr Kamban was the first person to discover the Faroe Islands. However, these two sources disagree on when he left and why. The Flateyjarbók says Grímr Kamban moved there during the rule of Harald Hårfagre (between 872 and 930 AD). The Saga of Óláfr Tryggvason suggests Kamban lived in the Faroes much earlier. It says other Norse people came to the Faroe Islands because of Harald Hårfagre's harsh rule. This large move to the Faroes shows that people already knew where the Viking settlements were. This supports the idea that Grímr Kamban settled there earlier.

Grímr Kamban is known as the first Viking settler of the Faroe Islands. But his last name, Kamban, is from a Gaelic language. Writings from the Papar, who were Irish monks, show they left the Faroe Islands because of Viking raids.

The Faroes Before the 14th Century

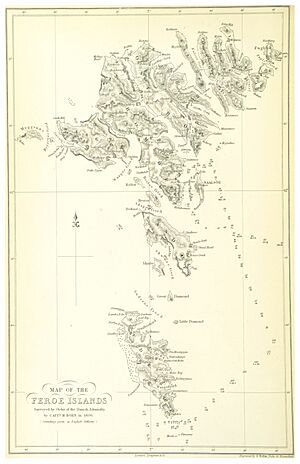

The name of the islands first appeared on the Hereford Mappa Mundi map in 1280. They were called farei. People have long thought the name comes from the Old Norse word fár, meaning "livestock". So, fær-øer means "sheep islands".

The main historical source for this time is the 13th-century book Færeyinga saga (Saga of the Faroese). But it's debated how much of it is true history. The Færeyinga saga only exists today as copies in other sagas. These include the Saga of Óláfr Tryggvason, Flateyjarbók, and one called AM 62 fol.

According to the Flateyjarbók, Grímr Kamban settled in Faroe when Harald Hårfagre was king of Norway (872–930). A slightly different story is in the Færeyinga saga version in Ólafs Saga Tryggvasonar:

There was a man named Grímr Kamban; he first settled in Faroe. But in the days of Harold Fairhair many men fled before the king's overbearing. Some settled in Faroe and began to dwell there, and others sought to other waste lands.

This text suggests that Grímr Kamban settled in the Faroes before people fled from Harald Hårfagre. This could have been hundreds of years earlier. His first name, Grímr, is Norse. But his last name, Kamban, suggests he was of Gaelic origin. He might have been a mix of Norse and Irish. He could have come from a settlement in the British Isles, known as a Norse-Gael. These Norse-Gaels had married people who spoke Irish. This language was also spoken in Scotland at the time.

Evidence of mixed cultures in later settlers can be seen. Norse-Irish ring pins have been found in the Faroe Islands. Also, some Faroese words come from Middle Irish. Examples include "blak/blaðak" (buttermilk), "drunnur" (animal tail), "grúkur" (head), "lámur" (hand, paw), "tarvur" (bull), and "ærgi" (pasture).

Discoveries at Toftanes on Eysturoy show wooden crosses. These crosses seem to be based on Irish or Scottish designs. This suggests some early settlers were Christian. It's also thought that the round stone walls around early church sites in the Faroes are like Celtic Christian styles. Genetic research also supports this idea. It shows that many Norse settler women in the Faroe Islands had Celtic ancestors.

If people settled in the Faroes during Harald Hårfagre's rule, it's possible they already knew about the islands. This could be from earlier visitors or settlers.

The fact that immigrants from Norway also settled there is shown by a runestone. This stone was found in Sandavágur on Vágoy Island. It says:

Thorkil Onundsson, eastman (Norwegian) from Rogaland, settled first in this place (Sandavágur)

The term "eastman" (from Norway) is used here. This is like the term "westman" (from Ireland/Scotland). "Westman" is found in local place-names. For example, "Vestmanna-havn" means "Irishmen's harbour" in the Faroes. And "Vestmannaeyjar" means "Irishmen's islands" in Iceland.

According to Færeyinga saga, there was an old meeting place called Tinganes in Tórshavn. This was an Alþing, or All-council. Laws were made here and problems were solved. All free men could meet in the Alþing. It was a parliament and a law court for everyone. Historians believe the Alþing was set up between 800 and 900 AD.

The islands officially became Christian around the year 1000. The Diocese of the Faroe Islands was based at Kirkjubøur. There were 33 Catholic bishops there.

The Faroes became part of the Kingdom of Norway in 1035. In the early 11th century, Sigmundur Brestisson was sent from Norway. His family had been powerful in the southern islands but were almost wiped out by invaders. He had escaped to Norway. King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway sent him to take control of the islands. Sigmundur brought Christianity. Even though he was later murdered, Norway's rule continued.

King Sverre of Norway grew up in the Faroes. He was the stepson of a Faroese man. He was also related to Roe, the bishop of the islands.

Foreign Trade and Influence: 14th Century to World War II

The 14th century marked the start of a long period where foreign powers influenced the Faroese economy. Trading rules were set up. All Faroese trade had to go through Bergen, Norway. This was to collect customs tax. At the same time, the Hanseatic League was growing stronger. This group of German trading cities threatened Scandinavian trade. Norway tried to stop them but couldn't. This was because the Black Death had greatly reduced Norway's population.

Norway's rule continued until 1380. Then, the islands became part of the Kalmar Union. The islands were still owned by the Norwegian crown. In 1380, the Alþing was renamed the Løgting. By then, it was mostly just a law court.

In the 1390s, Henry I Sinclair, Earl of Orkney, took control of the islands. He was a vassal of Norway. For some time, the Faroes were part of the Sinclair principality in the North Atlantic.

Digs on the islands show that pigs were kept until after the 13th century. This was unusual compared to Iceland and Greenland. People in the Faroes at Junkarinsfløtti relied on birds, especially puffins, for much longer. They did this more than other Viking Age settlers in the North Atlantic islands.

English adventurers caused many problems for the islanders in the 16th century. Magnus Heinason, a man from Streymoy, was sent by Frederick II to clear the seas. He is still famous in many songs and stories.

The Reformation Era

In 1535, Christian II, who had lost his throne, tried to regain power. He fought against King Christian III. Several powerful German companies supported Christian II. But he eventually lost. In 1537, the new King Christian III gave a German trader, Thomas Köppen, special trading rights in the Faroes.

These rights came with rules. Only good quality goods were to be supplied by the Faroese. The goods had to be bought at their fair market value. Traders also had to deal honestly with the Faroese.

Christian III also brought Lutheranism to the Faroes. This was to replace Catholicism. This change took five years. During this time, Danish was used instead of Latin in churches. Church property was also given to the state. The bishop's office at Kirkjubøur, south of Tórshavn, was also ended. You can still see parts of the old cathedral there.

After Köppen, others took over the trading monopoly. But the economy suffered because of the Dano-Swedish war between Denmark–Norway and Sweden. During this time, most Faroese goods (like wool products, fish, and meat) went to the Netherlands. They were sold at set prices. However, the rules of the trading agreement were often ignored. This caused delays and shortages of Faroese goods. It also led to lower quality. As the trading monopoly started to fail, smuggling and piracy became common.

From the 1600s Onwards

- Further information: Sloop period

The Danish king tried to fix the problem. He gave the Faroes to a court official named Christoffer Gabel. Later, his son Frederick took over. But the Gabel family's rule was harsh. This made the Faroese very unhappy. So, in 1708, Denmark–Norway gave control of the islands and the trading monopoly back to the central government.

However, the government also struggled to keep the economy going. Many merchants lost money. Finally, on January 1, 1856, the trading monopoly was ended.

The Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland became part of Denmark in 1814. This happened at the Peace of Kiel, when the union of Denmark–Norway broke up.

In 1816, the Løgting (the Faroese parliament) was officially closed. A Danish court system replaced it. Danish became the main language, and Faroese was discouraged. In 1849, Denmark got a new constitution. It was put into use in the Faroes in 1850. This gave the Faroese two seats in the Rigsdag (the Danish parliament).

However, in 1852, the Faroese managed to bring back the Løgting. It became a county council with an advisory role. Many people hoped for independence in the future. The late 19th century saw more support for home rule or independence. But not everyone agreed.

Meanwhile, the Faroese economy grew. Large-scale fishing was introduced. The Faroese could now fish in the big Danish waters in the North Atlantic. Living standards improved, and the population grew. Faroese was made a standard written language in 1890. But it was not allowed in public schools until 1938. It wasn't allowed in the church until 1939.

The Faroe Islands During World War II

During the Second World War, Nazi Germany invaded and occupied Denmark. To stop Germany from taking the Faroes, the British launched Operation Valentine. They invaded and occupied the islands themselves. The Faroes were in a very important location in the North Atlantic. Germany could have used them as a submarine base during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Instead, the British built an airbase on Vágar. This airport is still used today as Vágar Airport. Faroese fishing boats also supplied a lot of fish to the UK. This was very important because of food rationing in Britain.

The Løgting gained the power to make laws during the war. The Danish prefect, Carl Aage Hilbert, kept the power to carry out those laws. The Faroese flag was recognized by the British. There were some attempts to declare full independence during this time. But the UK had promised not to get involved in the Faroes' internal affairs. They also promised not to act without permission from a free Denmark. The experience of governing themselves during the war was very important. It helped pave the way for formal self-rule in 1948.

Most people in the Faroes liked the British presence. They especially preferred it to German occupation. About 150 marriages happened between British soldiers and Faroese women. However, the large number of British soldiers on Vágar did cause some local tensions. The British presence also led to a lasting love for British chocolate and sweets. These are easy to find in Faroese shops but are not common in Denmark.

After World War II: Home Rule

After Denmark was freed and World War II ended, the last British troops left in September 1945. Until 1948, the Faroes were officially a Danish county.

A vote on full independence was held in 1946. Most people voted for independence. However, the Danish Government and king did not recognize this vote. Only two-thirds of the population had voted. So, the Danish king ended the Faroese government. The next elections for the Løgting were won by a group that did not want independence.

Instead, the Faroes gained a high level of self-governance in 1948. This was through the Act of Faroese Home Rule. Faroese became an official language. Danish is still taught as a second language in schools. The Faroese flag was also officially recognized by Danish authorities.

In 1973, Denmark joined the European Community (now the European Union). The Faroes chose not to join. This was mainly because of disagreements over fishing limits.

The 1980s saw more support for Faroese independence. Unemployment was very low, and the Faroese had a high standard of living. But the Faroese economy relied almost entirely on fishing. In the early 1990s, there was a big drop in fish stocks. This was because of overfishing with new high-tech equipment. At the same time, the government was spending too much money. The national debt reached 9.4 billion Danish krones (DKK).

In October 1992, the Faroese national bank (Sjóvinnurbankin) faced serious problems. It had to ask Denmark for a huge financial rescue. The first amount was 500 million DKK. This eventually grew to 1.8 billion DKK. This was on top of the yearly grant of 1 billion DKK.

Strict measures were put in place. Public spending was cut. There was an increase in tax and VAT. Public employees had their wages cut by 10%. Much of the fishing industry faced financial trouble. There was talk of reducing the number of fish farms and ships.

During this time, many Faroese (6%) decided to move away. Most went to Denmark. Unemployment rose to as much as 20% in Tórshavn. It was even higher in the smaller islands.

In 1993, Sjóvinnurbankin merged with the second largest bank, Føroya Banki. A third bank went bankrupt. Meanwhile, there was a growing international boycott of Faroese products. This was because of the grindadráp (whaling) issue. The independence movement became less strong. Denmark, on the other hand, was left with the Faroe Islands' unpaid bills.

Recovery measures were put in place and mostly worked. Unemployment reached its highest point in January 1994 at 26%. After that, it fell. It was 10% in mid-1996 and 5% in April 2000. The fishing industry mostly survived. Fish stocks also increased. The yearly catch was 100,000 tons in 1994. It rose to 150,000 tons in 1995, and 375,000 tons in 1998. Moving away also decreased to 1% in 1995. There was a small population increase in 1996. Also, oil was found nearby.

By the early 21st century, the problems in the Faroese economy were fixed. Many people started thinking about independence from Denmark again. However, a planned vote in 2001 on steps towards independence was called off. This happened after Danish Prime Minister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen said that Danish money grants would stop within four years if the vote was "yes".

See also

In Spanish: Historia de las Islas Feroe para niños

In Spanish: Historia de las Islas Feroe para niños

- Timeline of Faroese history

- Faroese language conflict

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |