Icelanders facts for kids

|

|

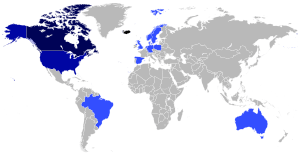

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 388,900 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 101,795 | |

| 42,716 | |

| 9,308 | |

| 8,274 | |

| 5,454 | |

| 2,225 | |

| 1,802 | |

| 1,500 | |

| 1,122 | |

| 1,046 | |

| 980 | |

| 492 | |

| 223 | |

| Other countries combined | c. 3,000 |

| Languages | |

| Icelandic | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheranism (mainly the Church of Iceland); Neo-pagan; Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox minorities among other faiths; secular. Historically Norse paganism, and Catholicism (c. 1000 – 1551). See Religion in Iceland |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Germanic peoples (especially Norwegians, Danes, Faroese Islanders) |

|

Icelanders (Icelandic: Íslendingar) are a group of people who live in the island country of Iceland. They speak Icelandic, which is a North Germanic language.

Icelanders created their country in 930 A.D. when their first parliament, called the Althing, met. Over time, Iceland was ruled by kings from Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. However, on December 1, 1918, Iceland became fully independent from Denmark and formed the Kingdom of Iceland. Later, on June 17, 1944, Iceland became a republic, which means it is now governed by elected officials, not a king or queen. Most Icelanders follow the Lutheran religion. Studies of history and DNA show that many of the first settlers were from Norway and Ireland or Scotland.

History of Iceland

Iceland is a relatively new land, formed about 20 million years ago by volcanic eruptions on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It was one of the last large islands to be settled by humans. Most people agree that the first permanent settlers arrived in 874 AD.

Early Settlers Arrive

The first Viking to see Iceland was Garðar Svavarsson. He got lost while sailing from Norway to the Faroe Islands. His reports led to the first attempts to settle Iceland. Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson was the first Norseman to sail to Iceland on purpose. His journey is written in the Landnámabók (Book of Settlements), and he is said to have named the island Ísland, which means Iceland.

The first permanent settler is usually thought to be a Norwegian leader named Ingólfr Arnarson. He settled with his family around 874 AD in a place he called "Bay of Smokes," or Reykjavík in Icelandic.

After Ingólfur, other Norwegians sailed across the Atlantic Ocean with their families, animals, and belongings. They were escaping the rule of Harald Fairhair, the first King of Norway. These settlers traveled about 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) in their Viking longships. Many of these people were from Norway, Ireland, or Gaelic Scotland. The Irish and Scottish Gaels were often servants or descendants of Norse people who had lived in Scotland and Ireland.

The period of settlement in Iceland, called Landnámsöld in Icelandic, lasted from 874 to 930 AD. By 930, most of the island had been claimed, and the Althing, Iceland's first assembly, was founded at Þingvellir.

Challenges and Conflicts

In 930 AD, the leaders and their families met at Þingvellir near Reykjavík and created the Althing. This was Iceland's first national assembly, but it didn't have the power to make sure its laws were followed. By 1262, fights between rival leaders made Iceland so divided that they asked King Haakon IV of Norway to help settle their disputes. This period is known as the Age of the Sturlungs.

Iceland was under Norwegian rule until 1380. Then, both Iceland and Norway came under the control of the Danish Crown. When Denmark became an absolute monarchy, Iceland lost its right to make its own laws. This meant Iceland lost its independence and went through almost 300 years of hardship. Denmark didn't see Iceland as a colony to support. This led to problems, especially a lack of defense, which meant pirates often attacked Iceland's coasts.

Unlike Norway, Denmark didn't need Iceland's fish or wool. This caused a big problem for Iceland's trade, and no new ships were built. In 1602, the Danish government even stopped Iceland from trading with other countries. In the 18th century, the weather also became very cold, making life even harder.

In 1783–84, the Laki volcano in the south of Iceland erupted. This eruption released a huge amount of lava and ash. The ash caused a cooling effect in the Northern Hemisphere. For Iceland, the results were terrible. About 25-33% of the population died from famine in 1783 and 1784. Also, about 80% of sheep, 50% of cattle, and 50% of horses died from a disease caused by the chemicals released. This disaster is known as the Mist Hardship (Icelandic: Móðuharðindin).

The Althing was stopped for a few decades in 1798–99 but was brought back in 1844. It was moved to Reykjavík, the capital, after being held at Þingvellir for over nine centuries.

Independence and Growth

The 19th century brought much better times for Icelanders. A protest movement was led by Jón Sigurðsson, an important politician, historian, and expert on Icelandic literature. Inspired by new ideas from Europe, Jón strongly argued for Iceland to remember its national identity and make political and social changes to help it grow.

In 1854, the Danish government eased the trade ban from 1602. Iceland slowly started to reconnect with other European countries economically and socially. This renewed contact also led to a rebirth of Icelandic arts, especially its literature. Twenty years later, in 1874, Iceland received its own constitution. Icelanders today believe Jón's efforts were very important for their country's economic and social comeback.

Iceland became fully independent from Denmark in 1918 after World War I. It was called the Kingdom of Iceland. The King of Denmark was also the King of Iceland, but Iceland was mostly separate. On June 17, 1944, the monarchy was ended, and a republic was formed. This happened on Jón Sigurðsson's 133rd birthday and ended almost six centuries of ties with Denmark.

People and Society

Icelandic Ancestry

Because Iceland started with a small number of people and was quite isolated, Icelanders have often been seen as very similar genetically compared to other European groups. This, along with detailed family records going back to the first settlers, has made Icelanders a focus for genetic research. For example, scientists could learn a lot about the DNA of Hans Jonatan, Iceland's first known black resident, from his descendants.

Genetic studies show that most of the DNA in Icelanders today comes from the first settlers. This means there hasn't been much immigration since then. These studies show that the first people in Iceland came from Ireland, Scotland, and Scandinavia. About 62% of Icelandic women's family lines come from Scotland and Ireland, while 75% of Icelandic men's family lines come from Scandinavia.

Some studies have found other ancestries too. A small number of Icelanders have a very old family line that might be traced back to the first people who settled the Americas about 14,000 years ago. This suggests that a tiny part of Icelandic ancestry comes from Native American people, possibly from the Norse settlements in Greenland and North America.

Moving Away from Iceland

Greenland

The first Europeans to settle in Greenland were Icelanders led by Erik the Red in the late 900s. About 500 people moved there. The isolated fjords (narrow inlets of the sea) in this harsh land had enough grass for cattle and sheep, but it was too cold for growing crops. Royal trade ships from Norway sometimes visited Greenland to trade for walrus tusks and falcons. The population grew to about 3,000 people in two communities before disappearing in the 1400s.

North America

Stories say that Icelanders first came to North America around 1006, settling in a place called Vinland. This settlement was believed to be short-lived and abandoned by the 1020s. It wasn't until the 1960s that archaeologists found proof of this Norse site, now called L'Anse aux Meadows, which existed almost 500 years before Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas.

More recently, Icelanders began moving to North America in 1855, with a small group settling in Spanish Fork, Utah. Another group formed a colony in Washington Island, Wisconsin. Many Icelanders started moving to the United States and Canada in the 1870s, often settling near the Great Lakes. These settlers were escaping famine and too many people in Iceland. Today, there are large communities of people with Icelandic roots in both the United States and Canada. Gimli, Manitoba in Canada has the largest population of Icelanders outside of Iceland itself.

Moving to Iceland

Since the mid-1990s, more people have been moving to Iceland. By 2017, about 10.6% of Iceland's residents were first-generation immigrants (people born abroad with foreign-born parents and grandparents). The number of foreign-born people becoming Icelandic citizens has also increased. This means that Iceland's identity is slowly becoming more multicultural.

Icelandic Culture

Language and Stories

Icelandic is the official language of Iceland. It is a North Germanic language. The grammar of Icelandic is similar to Latin and Old English, and almost the same as Old Norse.

Old Icelandic literature includes several types of writings. The most famous ones are Eddic poetry, skaldic poetry, and saga literature. Eddic poetry tells heroic and mythological stories. Skaldic poetry praises people. Saga literature is prose (like stories or novels) that can be pure fiction or based on history.

Written Icelandic has not changed much since the 1200s. Because of this, modern readers can still understand the Icelanders' sagas. The sagas tell about events in Iceland in the 900s and early 1000s. They are considered the most famous pieces of Icelandic literature.

The Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, along with the sagas, are the main works of Icelandic literature. The Poetic Edda is a collection of poems and stories from the late 900s. The Prose Edda is a guide to poetry that includes many stories from Norse mythology.

Religion in Iceland

Iceland became Christian around 1000 AD. This event is called the kristnitaka. Today, while many Icelanders are not very religious in their daily lives, the country is still mostly Christian culturally. The Lutheran church includes about 84% of the population.

While early Icelandic Christianity was more relaxed than traditional Catholicism, a religious movement from Denmark in the 1700s, called Pietism, had a big impact. It encouraged religious activities and discouraged other forms of fun, which made Icelanders seem a bit serious for a long time. However, it also led to a lot more printing, and today Iceland has one of the highest rates of literacy in the world.

Even though Catholicism was replaced by Protestantism during the Protestant Reformation, most other world religions are now present in Iceland. There are small Protestant churches, Catholic groups, and even a growing Muslim community made up of immigrants and local converts. Something unique to Iceland is the fast-growing Ásatrúarfélag, which is a legally recognized revival of the old Nordic religion of the first settlers.

Food and Meals

Icelandic cuisine mainly includes fish, lamb, and dairy foods. Fish used to be the main part of an Icelander's diet, but recently meats like beef, pork, and poultry have become more common.

Iceland has many traditional foods called Þorramatur. These include smoked and salted lamb, singed sheep heads, dried fish, smoked and pickled salmon, and cured shark. Andrew Zimmern, a chef who travels the world for his show Bizarre Foods with Andrew Zimmern, once said that fermented shark fin from Iceland was the most disgusting thing he had ever eaten! Fermented shark fin is a type of Þorramatur.

Arts and Music

The oldest type of Icelandic music was the rímur, which were epic tales from the Viking era often sung without instruments. Christianity was very important in developing Icelandic music, with many hymns written in the local language. Hallgrímur Pétursson, a poet and priest, wrote many of these hymns in the 1600s. Because Iceland was quite isolated, its music kept its unique regional style. It wasn't until the 1800s that the first pipe organs, common in European church music, appeared on the island.

Many singers, groups, and types of music have come from Iceland. Most Icelandic music has lively folk and pop traditions. Some well-known recent groups and singers include Voces Thules, The Sugarcubes, Björk, Sigur Rós, and Of Monsters and Men.

Iceland's national anthem is "Ó Guð vors lands" (English: "Our Country's God"). It was written by Matthías Jochumsson, with music by Sveinbjörn Sveinbjörnsson. The song was created in 1874 to celebrate Iceland's one thousandth anniversary of settlement.

Sports in Iceland

Iceland's men's national football team played in their first FIFA World Cup in 2018. Before that, they reached the quarter-finals of their first major international tournament, UEFA Euro 2016. The women's national football team has not yet reached a World Cup; their best result at a major international event was reaching the quarter-finals in UEFA Women's Euro 2013.

Iceland first participated in the 1912 Summer Olympics but didn't compete again until the 1936 Summer Olympics. Their first appearance at the Winter Games was in the 1948 Winter Olympics. In 1956, Vilhjálmur Einarsson won an Olympic silver medal in the triple jump. The Icelandic national handball team has also been quite successful, winning a silver medal at the 2008 Olympic Games and a bronze medal at the 2010 European Men's Handball Championship.

In Spanish: Pueblo islandés para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo islandés para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |