Snorri Sturluson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Snorri Sturluson

|

|

|---|---|

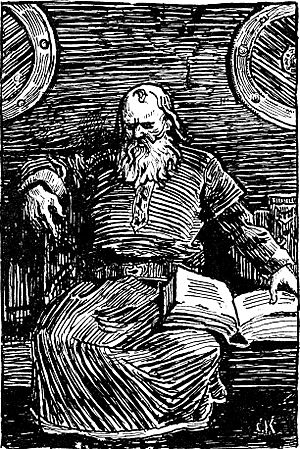

Snorri Sturluson by Christian Krohg (1890s)

|

|

| Born | 1179 Hvammur í Dölum, Dalasýsla, Icelandic Commonwealth

|

| Died | September 22, 1241 (aged 61–62) Reykholt, Iceland

|

| Occupation | Lawspeaker, author, poet, historian, politician |

| Era | Age of Sturlungs |

| Organization | Althing |

|

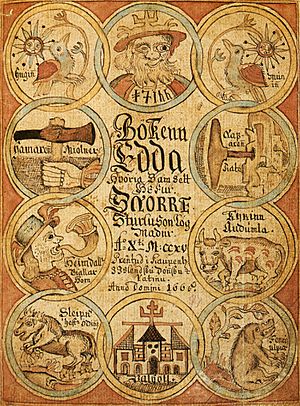

Notable work

|

Prose Edda, Heimskringla |

| Spouse(s) |

Herdís Bersadóttir

(m. 1199; estranged 1206) |

| Partner(s) | Hallveig Ormsdóttir (1224–1241) Guðrún Hreinsdóttir Oddny Þuríður Hallsdóttir |

| Children | ~6 |

| Parent(s) | Sturla Þórðarson Guðný Böðvarsdóttir |

| Relatives | Sighvatr Sturluson (brother) Steinvör Sighvatsdóttir (niece) Þórður kakali Sighvatsson (nephew) Sturla Sighvatsson (nephew) Óláfr Þórðarson (nephew) Sturla Þórðarson (nephew) Kolbeinn ungi Arnórsson (son-in-law) |

| Family | Sturlungar family clan |

Snorri Sturluson (IPA: [ˈsnorːe ˈsturloˌson]; Icelandic: [ˈstnɔrːɪ ˈstʏ(r)tlʏˌsɔːn]; 1179 – 22 September 1241) was a very important Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was chosen twice to be the lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, called the Althing. This was a very respected job.

Many people believe Snorri wrote or helped put together the Prose Edda. This book is a main source for what we know about Norse mythology today. He also wrote Heimskringla, which tells the history of the Norwegian kings. This history starts with old legends and goes up to early medieval times in Scandinavia. Because of his writing style, some also think Snorri wrote Egil's saga. Sadly, Snorri was killed in 1241 by people who said they worked for the King of Norway.

Contents

Snorri Sturluson: A Famous Icelandic Writer

Early Life and Education

Snorri Sturluson was born in 1179 in a place called Hvammur í Dölum in Iceland. His family, the Sturlungar, was very rich and powerful. His parents were Sturla Þórðarson and Guðný Böðvarsdóttir. He had two older brothers and several other siblings.

When Snorri was about three or four years old, he went to live with Jón Loftsson in Oddi, Iceland. Jón Loftsson was related to the Norwegian royal family. Snorri's father had a problem with a priest, and Jón Loftsson helped settle it. As a way to make things right, Jón offered to raise and teach Snorri.

Living with Jón Loftsson meant Snorri got a great education. He went to a school in Oddi and learned a lot. This also helped him make important friends and connections. Snorri never went back to live with his parents. His father passed away in 1183. In 1199, Snorri married a woman named Herdís. Through her father, Snorri gained land and a position as a chieftain. He soon became even wealthier.

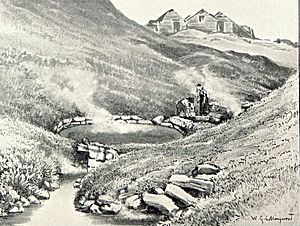

Snorri and Herdís lived together for four years. They had at least two children, Hallbera and Jón. In 1206, Snorri moved to Reykholt to manage an estate. He made many improvements there, including an outdoor bath. This bath was fed by hot springs. The bath, known as Snorralaug, and some buildings from his time are still there today. During his first years in Reykholt, he had five more children with three different women.

Life as a Leader and Writer

Snorri quickly became famous as a poet. He was also a skilled lawyer. In 1215, he became the lawspeaker of the Althing. This was the most important public job in Iceland at the time. It was a position of great respect.

In 1218, Snorri left his lawspeaker role and traveled to Norway. The king of Norway had invited him. There, he became good friends with the young King Hákon Hákonarson and his co-ruler, Jarl Skúli. Snorri stayed with the jarl for the winter. They gave him many gifts, including a ship. In return, Snorri wrote poems about them. In 1219, he met a Swedish lawspeaker and his wife. They were related to royalty and likely taught Snorri about the history of Sweden.

Snorri was very interested in history and culture. The Norwegian rulers wanted Snorri to help them. They gave him a special title, like a knight, and he promised to be loyal to them. The king hoped to bring Iceland under Norwegian rule. Snorri, as a key member of the Althing, could help make this happen.

In 1220, Snorri went back to Iceland. By 1222, he was again the lawspeaker of the Althing. He held this position until 1232. He was chosen mainly because of his fame as a poet. In politics, he supported Iceland joining Norway. This idea made some of the other chiefs his enemies. In 1224, Snorri married Hallveig Ormsdottir. She was a wealthy widow and a granddaughter of Jón Loftsson. They shared their property. Their own children did not live to be adults, but Hallveig's two sons and seven of Snorri's children did.

Snorri was the most powerful chieftain in Iceland between 1224 and 1230.

Challenges and Later Life

Many other chiefs did not like Snorri's support for the Norwegian king. This was especially true for other members of his own family, the Sturlungar. Snorri seemed to want to gain more power over them. Then he could offer Iceland to the king.

A time of family fighting followed. Snorri tried to gather forces to fight his brother Sighvatur and nephew Sturla Sighvatsson. But just before a battle, he sent his forces away and tried to make peace.

Sighvatur and Sturla, with 1000 men, forced Snorri to leave his home. Snorri sought safety with other chiefs. His son, Órækja, started small attacks in western Iceland. The conflict grew into a war.

King Haakon IV tried to help from Norway. He invited all the chiefs of Iceland to a peace meeting in Norway. Sighvatur understood that this was a trap. He knew what could happen to the chiefs in Norway. Instead of killing his opponents, he pushed them to accept the king's offer.

Órækja was captured by Sturla during a peace talk. Another cousin, Þorleifur, came to help Snorri with 800 men. But Snorri left him on the battlefield because of a disagreement. In 1237, Snorri decided it was best to join the king in Norway.

The End of the Commonwealth

King Haakon IV of Norway had many problems during his rule. There were civil wars and plots against him. But he still managed to make Norway stronger.

When Snorri arrived in Norway for the second time, the king saw that Snorri was not a reliable helper anymore. The conflict between King Haakon and Jarl Skúli was turning into a civil war. Snorri stayed with the jarl, who gave him the title of jarl, hoping to gain his loyalty. In August 1238, Snorri's brother Sighvatur and four of his sons were killed in Iceland. This happened in a battle against other chiefs they had angered. Snorri, Órækja, and Þorleifur asked to go home. But the king said no. He ordered Snorri to stay in Norway. However, Jarl Skúli gave them permission and helped them find a ship.

Snorri decided to disobey the king's orders. He famously said, 'út vil ek' (meaning 'I will go home'). He returned to Iceland in 1239. The king was busy fighting Skúli, who declared himself king in 1239. Skúli was defeated and killed in 1240. Meanwhile, Snorri took back his chieftainship. He tried to take Gissur to court for the deaths of his brother and nephew. A meeting of the Althing was planned for 1241. But Gissur and Kolbein arrived with many men. Snorri and his men gathered around a church. Gissur chose to pay fines instead of attacking.

Snorri's Last Days

In 1240, King Haakon sent two agents to Gissur with a secret order to kill or capture Snorri. Gissur was invited to join the movement to unite Iceland with Norway. His first attempt to capture Snorri at the Althing failed.

Snorri's wife, Hallveig, passed away naturally. Her sons and Snorri's children argued over the inheritance. Hallveig's sons asked their uncle Gissur for help. Gissur met with them and Kolbein the Younger and showed them the king's letter. Hallveig's son Orm refused to help. Soon after, Snorri received a secret message warning him, but he could not understand it.

Gissur led seventy men in a surprise attack on Snorri's house. Snorri Sturluson was killed in his home in Reykholt in the autumn of 1241. He tried to hide in the cellar. There, Símon knútur told Arni the Bitter to strike him. Snorri said: Eigi skal höggva!—"Do not strike!" Símon replied: "Högg þú!" — "You strike now!" Snorri again said: Eigi skal höggva!—"Do not strike!" These were his last words.

This act was not popular in Iceland or Norway. To make it seem less bad, the king said that if Snorri had surrendered, he would have been spared. This shows how much influence the king now had in Iceland. King Haakon continued to gain control over the chiefs of Iceland. In 1262, the Althing agreed to unite with Norway. Iceland became part of the Norwegian kingdom.

Why Snorri Sturluson is Remembered

Snorri Sturluson's writings give us important information about people and events in Northern Europe. This is especially true for times when not much other information exists. For example, his work helps us understand the relationship between England and Scandinavia in the 10th and 11th centuries. Snorri is seen as a very important figure for this reason. One historian said his work was "better than anything else that the Middle Ages have left us of historical literature." He also wrote an early account of the discovery of Vinland.

Snorri Sturluson's legacy also played a role in politics long after his death. His writings could be used to support the claims of later Norwegian kings about how old and widespread their rule was. Later, his book Heimskringla helped create a national identity during the Norwegian romantic nationalism in the mid-1800s.

How Icelandic people see Snorri today has been shaped by their history. When Iceland wanted to become independent from Denmark, Snorri's story was used to help build national pride. People sometimes judge Snorri and other leaders of his time based on modern ideas like state, independence, and nation.

The famous writers Jorge Luis Borges and María Kodama studied and translated parts of the Gylfaginning into Spanish. They also wrote about Snorri's life in the book's introduction.

A quote from Snorri's Edda, "Nine worlds I remember," is used in Carl Sagan's book Cosmos.

Honoring Snorri Sturluson

- There is a street named Snorres gate in Oslo, Norway, named in his honor in 1896. There is also Snorrabraut, a main road in Reykjavik, Iceland, from the 1940s.

- A statue of Snorri Sturluson, made by Gustav Vigeland, is in Reykholt. The Norwegian Government gave this statue to Iceland in 1947. A copy of this statue was also put in Bergen, Norway in 1948.

- A picture of the Reykholt statue appeared on an Icelandic postage stamp in 1941.

- Norway also released a set of six postage stamps in 1941 to mark 700 years since his death. Each stamp showed pictures from Heimskringla.

- The Snorrastofa Cultural / Research Centre in Reykholt was opened on September 6, 1988. The President of Iceland and the King of Norway attended the opening.

In Spanish: Snorri Sturluson para niños

In Spanish: Snorri Sturluson para niños

- Sauðafell Raid

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |