Norse colonization of North America facts for kids

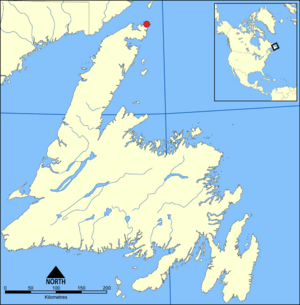

The Norse exploration of North America started in the late 900s. Norsemen, also known as Vikings, sailed across the North Atlantic Ocean and settled in Greenland. They also created a short-term settlement at the northern tip of Newfoundland, which is now called L'Anse-aux-Meadows.

In 1960, the remains of buildings were found at L'Anse aux Meadows. These buildings were about 1,000 years old. This discovery helped scientists learn more about the Norse in the North Atlantic. The settlement in Newfoundland was small and was quickly abandoned.

The Norse settlements in Greenland lasted for almost 500 years. L'Anse aux Meadows is the only confirmed Norse site in modern-day Canada. Other Norse trips probably happened, but there is no proof of any Norse settlement on the North American mainland lasting beyond the 1000s.

Some people have made up unproven theories about the Norse exploration of North America. However, archaeologists continue to find real evidence.

Contents

Norse Greenland

According to old Norse stories called the Sagas of Icelanders, Norse people from Iceland first settled Greenland in the 980s. These stories are helpful for understanding the beginning of the settlement, but they are not always completely accurate.

Erik the Red was a Norseman who was sent away from Iceland for a crime. He explored the empty southwestern coast of Greenland for three years. He wanted to attract settlers to the area, so he named it Greenland. He thought people would be more interested if the land had a good name. He built his farm, Brattahlid, in a long fjord named Eiriksfjord after him. He gave land to his followers.

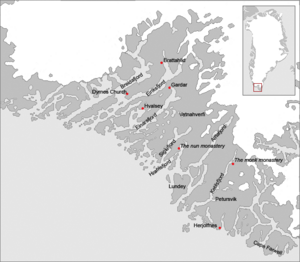

Norse Greenland had two main settlements. The Eastern Settlement was at the southwestern tip of Greenland. The Western Settlement was about 500 kilometers (310 miles) up the west coast, near where Nuuk is today. There was also a smaller settlement called the Middle Settlement. About 2,000 to 3,000 people lived there. Archaeologists have found at least 400 farms.

Norse Greenland had a bishop (a church leader) in a place called Garðar. The settlers traded goods like walrus ivory, furs, rope, and animal fat. They also exported live animals like polar bears and "unicorn horns" (which were actually narwhal tusks). In 1126, the people asked for a bishop. In 1261, they agreed to be ruled by the Norwegian king. They kept their own laws and became almost fully independent after 1349, when the Black Death plague happened. In 1380, Norway and Denmark joined together.

Trade and Decline

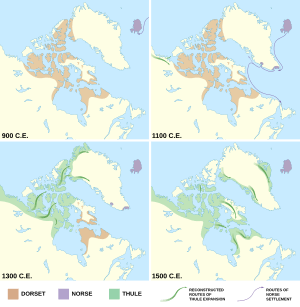

The Norse traded with the native people, whom they called the Skræling. The Norse met both Native Americans (like the Beothuk) and the Thule people, who are the ancestors of the Inuit. The Dorset culture had left Greenland before the Norse arrived.

Archaeologists have found Norse items far from Norse settlements. These include comb pieces, iron cooking tools, chisels, chess pieces, ship rivets, and carpenter's planes. A small ivory statue that looks like a European person was also found in an Inuit community house.

The Norse settlements in Greenland started to decline in the 1300s. The Western Settlement was abandoned around 1350. The last bishop in Garðar died in 1377. After a marriage was recorded in 1408, there are no more written records about the settlers. It is likely that the Eastern Settlement was gone by the late 1400s. The latest date found in Norse settlements from radiocarbon dating is 1430.

Several ideas explain why the settlements declined:

- The Little Ice Age made travel between Greenland and Europe harder. It also made farming more difficult.

- Even though hunting seals and other animals provided food, farming cattle was more important to the Norse.

- There were more farms available in Scandinavian countries because many people had died from famine and the Black Death plague.

- Greenlandic ivory may have been replaced in European markets by cheaper ivory from Africa.

Later, in 1721, a Norwegian missionary named Hans Egede was sent to Greenland. He wanted to see if the old Norse civilization was still there and if they were still Catholic. He found no Europeans, but his trip marked the start of Denmark taking control of the island again.

Climate and Life in Greenland

The Norse in Greenland lived in scattered fjords (narrow inlets of the sea). These fjords had places for their animals like cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, and cats. Farmers kept their livestock in stables during winter. They regularly culled (removed) some animals so the rest could survive the cold season. In warmer seasons, livestock were taken to pastures. The best pastures were controlled by the most powerful farms and the church.

The food from farming and livestock was topped up by hunting. They mainly hunted seals and caribou, and walrus for trade. The Norse especially relied on the Nordrsetur hunt, which was a group hunt for migratory harp seals in the spring.

Trade was very important for the Greenland Norse. They needed to import lumber because Greenland had few trees. In return, they exported things like walrus ivory, hides, live polar bears, and narwhal tusks. Their way of life was fragile because it depended on animal migration patterns and the health of the few fjords.

Part of the time the Greenland settlements existed was during the Little Ice Age. The climate was getting colder and wetter. This brought more storms, longer winters, and shorter springs. It also affected the migration of harp seals. Pasture land became smaller, and there was less food for animals in winter. This made it hard to keep livestock, especially for the poorer Norse.

Near the Eastern Settlement, temperatures stayed steady, but a long drought reduced food production. In spring, trips to hunt migratory harp seals became more dangerous due to more storms. Fewer harp seals meant the Nordrsetur hunts were less successful, making it very hard to find enough food.

The strain on resources made trade difficult. Over time, Greenland's exports lost value in the European market. This was because other countries offered similar goods, and there was less interest in what Greenland traded. Elephant ivory started to compete with walrus tusks, which were a main source of income for Greenland. There is also evidence that hunting too many walruses, especially males with larger tusks, caused walrus populations to drop.

It seems the Norse did not mix much with the Thule people of Greenland. There is evidence of contact in Thule archaeological sites, like ivory carvings of Norse people and metal tools. However, there is almost no Thule material found among Norse artifacts.

Older research suggested that the Norse declined not just because of climate change, but also because they were unwilling to adapt. For example, if the Norse had focused on hunting ringed seals (which could be hunted all year), food would have been less scarce in winter. Also, if they had used animal skin instead of wool for clothing, they could have lived better near the coast and not been so limited to the fjords.

However, newer research shows that the Norse did try to adapt. They increased their hunting of marine animals. Many marine animal bones are found at the settlements, showing more hunting when farmed food was scarce. Also, pollen records show that the Norse did not always destroy the small forests. Instead, they let overused areas regrow and moved to other places. Farmers also tried to adapt by fertilizing their lands to keep up with the new demands from the changing climate.

Even with these efforts, climate change was not the only problem. The economy was changing, and the goods they exported were losing value. Current research suggests that the Norse could not keep their settlements going because of both economic and climate changes happening at the same time.

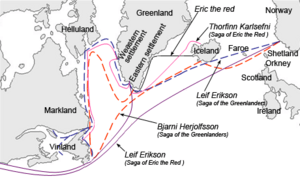

Vinland

According to the Icelandic sagas, the Norse began exploring lands west of Greenland a few years after settling Greenland. In 985, a merchant named Bjarni Herjólfsson was sailing from Iceland to Greenland. His ship was blown off course, and after three days, he saw land west of the fleet. Bjarni was only looking for his father's farm, but he told Leif Erikson about his discovery. Leif explored the area more closely and started a small settlement fifteen years later.

The sagas describe three different areas the Norse explored:

- Helluland: meaning "land of the flat stones."

- Markland: meaning "the land of forests." This was important for settlers in Greenland, where there were few trees.

- Vinland: meaning "the land of wine." This was found somewhere south of Markland. The settlement described in the sagas was built in Vinland.

Markland was first mentioned in the Mediterranean area in 1345 by a friar named Galvaneus Flamma. He probably heard about it from stories told in Genoa.

Leif's Winter Camp

- Greenland

- Helluland (Baffin Island)

- Markland (the Labrador Peninsula)

- Promontory of Vinland (the Great Northern Peninsula)

Leif used Bjarni's descriptions of routes, landmarks, currents, rocks, and winds. He sailed from Greenland westward across the Labrador Sea with a crew of 35. He used the same ship Bjarni had used. He described Helluland as "level and wooded, with broad white beaches wherever they went and a gently sloping shoreline."

Leif and others wanted his father, Erik the Red, to lead this trip. However, as Erik tried to join his son, he fell off his horse on wet rocks and was injured. So, he stayed behind.

Around the year 1000 AD, Leif spent the winter, probably near Cape Bauld on the northern tip of Newfoundland. He spent another winter at "Leifsbúðir" without any trouble. Then, he sailed back to Brattahlíð in Greenland to take care of his father.

Thorvald's Voyage

A couple of years later, Leif's brother Thorvald Eiriksson sailed to Vinland with 30 men. They spent the winter at Leif's camp. In the spring, Thorvald attacked nine native people who were sleeping under three skin-covered canoes. The ninth person escaped and soon returned to the Norse camp with a group of people. Thorvald was killed by an arrow that went through their barricade. Even though there was fighting, the Norse explorers stayed another winter and left the following spring.

Later, another of Leif's brothers, Thorstein, sailed to the New World to get his dead brother's body. But he died before leaving Greenland.

Karlsefni's Expedition

A few years later, Thorfinn Karlsefni, also known as "Thorfinn the Valiant," brought three ships with livestock and 160 men and women. Another source says there were 250 settlers. After a harsh winter, he sailed south and landed at Straumfjord. He later moved to Straumsöy.

There were some peaceful interactions between the native peoples and the Norse. They traded furs and gray squirrel skins for milk and red cloth. The natives tied the red cloth around their heads like a headdress.

There are different stories about what happened next. One story says that a bull belonging to Karlsefni ran out of the woods. This scared the natives so much that they ran to their skin-boats and rowed away. They returned three days later with a large group. The natives used catapults, throwing "a large sphere on a pole; it was dark blue in color" and about "the size of a sheep's stomach." It flew over the men's heads and "made an ugly din when it struck the ground."

The Norsemen retreated. Leif Erikson's half-sister Freydís Eiríksdóttir was pregnant and could not keep up. She called out to them to stop running from "such pitiful wretches." She said if she had weapons, she could do better. Freydís grabbed the sword of a man who had been killed by the natives. She scared the natives with the sword, and they ran away.

History of Discoveries

For many centuries, people were not sure if the Icelandic stories about Norse voyages to North America were true. The idea of Vikings in North America was discussed in a book called Northern Antiquities in 1770. But the sagas became widely known in 1837 when Carl Christian Rafn brought up the idea of a Viking presence in North America again.

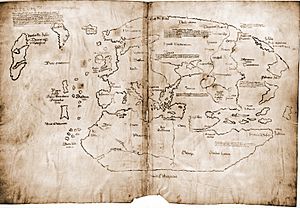

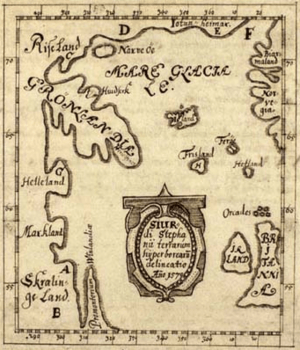

North America, called Winland, first appeared in written records around 1075. The most important stories about North America and early Norse activities were written in the 1200s and 1300s. In 1420, some Inuit captives and their kayaks were taken to Scandinavia. Norse sites were shown on the Skálholt Map, made by an Icelandic teacher in 1570. This map showed parts of northeastern North America and mentioned Helluland, Markland, and Vinland.

Proof of the Norse presence west of Greenland came in the 1960s. Archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad and her husband, Helge Ingstad, dug up a Norse site at L'Anse-aux-Meadows in Newfoundland. They found a bronze pin like those the Norse used to fasten their cloaks. They also found a stone oil lamp, a small spindle whorl (used for spinning thread), and a piece of a bone needle for knitting. A small, decorated brass fragment was also found. Much slag (waste from working with iron) and many iron boat nails or rivets were found at the site. This showed that iron working, carpentry, and boat repair happened there.

In 2012, Canadian researchers found possible signs of Norse outposts in Nanook at Tanfield Valley on Baffin Island. They also found signs on Nunguvik, Willows Island, and Avayalik. Unusual fabric cord found on Baffin Island in the 1980s was later identified as possibly Norse in 1999. This led to more exploration of the Tanfield Valley site to find connections between Norse Greenlanders and the native Dorset culture people.

In 2021, some wood from L'Anse aux Meadows was dated to the year 1021. This confirmed that the settlement was built by Norsemen. In the same year, Yale University said that the Vinland Map was a fake.

Unproven Claims

Some people have claimed to find runestones in North America, like the Kensington Runestone. However, these are usually considered fakes or misunderstandings of Native American rock carvings.

Many claims of Norse settlements in New England are not well-supported. Monuments claimed to be Norse include:

- The Stone Tower in Newport, Rhode Island

- The rock carvings on Dighton Rock, from the Taunton River in Massachusetts

- The runes on Narragansett Runestone

Kensington Runestone

In late 1898, a Swedish immigrant named Olof Öhman said he found this runestone in Kensington, Minnesota. He said it was lying face down near a small hill in a wet area. After a professor named Olaus J. Breda studied the carvings, she said the runestone was a fake. She published an article in 1910 saying it was not real. Other Scandinavian language experts also agreed that the Kensington inscription was a fraud.

Horsford's Norumbega

The 1800s chemist Eben Norton Horsford believed the Charles River Basin was connected to places described in the Norse sagas, especially a place called Norumbega. He published books about this and had plaques, monuments, and statues put up to honor the Norse. However, most historians and archaeologists did not support his ideas.

Some writers in the 1800s used these false ideas about Viking history to promote harmful beliefs.

Vinland Map

In the mid-1960s, Yale University announced they had bought a map supposedly drawn around 1440. This map showed Vinland and a note about Norse voyages to the area. However, some experts doubted if the map was real because of problems with the language and how it was drawn. Chemical tests of the map's ink later raised more doubts. Scientific debate continued until 2021, when the university finally said that the Vinland Map was a forgery.

Misattributed Archeological Findings

In 2015, archaeological findings at Point Rosee, on the southwest coast of Newfoundland, were first thought to be a 10th-century Norse settlement. They seemed to show a turf wall and evidence of roasting bog iron ore. However, excavations in 2016 suggested that the turf wall and roasted bog iron ore were actually caused by natural processes.

The possible settlement was first found using satellite imagery in 2014. Archaeologists dug in the area in 2015 and 2016. Birgitta Linderoth Wallace, a leading expert on Norse archaeology in North America, was unsure if Point Rosee was a Norse site. Archaeologist Karen Milek, also a Norse expert, was part of the 2016 excavation. She also doubted it was a Norse site because there were no good places for Norse boats to land, and steep cliffs were between the shore and the dig site. In their report from November 8, 2017, the co-directors of the excavation, Sarah Parcak and Gregory Mumford, wrote that they "found no evidence whatsoever for either a Norse presence or human activity at Point Rosee prior to the historic period." They also said that "none of the team members, including the Norse specialists, deemed this area as having any traces of human activity."

How Long Did Norse Contact Last?

Norse settlements in North America were meant to use natural resources like furs and especially lumber, which was scarce in Greenland. It is not clear why these short-term settlements did not become permanent. One reason was likely hostile relations with the native peoples, whom the Norse called the Skræling.

However, it seems that occasional trips to Markland for food, timber, and trade with locals might have continued for as long as 400 years.

James Watson Curran wrote: "From 985 to 1410, Greenland was in touch with the world. Then silence. In 1492 the Vatican noted that no news of that country 'at the end of the world' had been received for 80 years, and the bishopric of the colony was offered to a certain ecclesiastic if he would go and 'restore Christianity' there. He didn't go."

See also

In Spanish: Asentamientos vikingos en Groenlandia y Terranova para niños

In Spanish: Asentamientos vikingos en Groenlandia y Terranova para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |