Vinland Map facts for kids

The Vinland Map was once thought to be a very old map from the 1400s. It seemed to show Norse explorers had visited North America long before Christopher Columbus. The map first appeared in 1957 and was bought by Yale University. It became famous in 1965 when it was shown to the public as a "real" map from before Columbus's time.

Besides showing Africa, Asia, and Europe, the map also showed a landmass southwest of Greenland in the Atlantic Ocean. This land was called Vinland (Vinlanda Insula). The map said that Europeans had visited this area in the 11th century.

However, soon after it was shown, experts began to think it might be a fake. Chemical tests later proved that one of the main ink ingredients was a modern pigment from the 20th century. In 2018, after many studies, experts at Yale University officially declared that the Vinland Map was a modern forgery.

Contents

How Yale Got the Map

The Vinland Map first appeared in 1957. This was three years before the discovery of a real Norse site at L'Anse aux Meadows in 1960. A London book dealer first tried to sell it to the British Museum, but they said no.

Soon after, an American dealer named Laurence C. Witten II bought the map for $3,500. He then offered it to his old university, Yale University. At first, Yale was suspicious. One reason was that the wormholes in the map and a text bound with it (called the Tartar Relation) did not line up.

Later, a Yale librarian found another old book that seemed to be the missing piece. This book had wormholes that matched both the map and the Tartar Relation. It looked like all three pieces had once been together. Most old ownership marks had been removed from the books, except for a small pink stamp.

Yale could not afford the map's price. Also, Witten would not say where the map came from. So, Yale contacted another former student, Paul Mellon. He agreed to buy the map for about $300,000 and give it to the university, but only if it could be proven real.

Mellon wanted the map's existence to be kept secret until a scholarly book about it was finished. Only a few people who had seen the map before Mellon bought it were chosen to write the book. After years of study, the book was ready. Mellon then gave the map to Yale. The map was finally shown to the world in 1965, the day before Columbus Day.

Questions and Investigations (1966–2018)

Many experts who reviewed the book about the Vinland Map quickly found reasons to doubt its authenticity. A year later, a conference was held to discuss the map. Many more questions were raised there.

Map Details and Strange Features

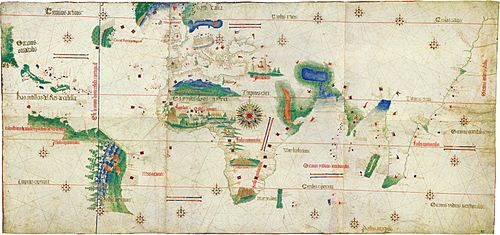

Experts noticed that the Vinland Map looked a lot like a map made in the 1430s by an Italian sailor named Andrea Bianco. However, some similarities and differences were very odd. For example, the Vinland Map cut off Africa where Bianco's map had a page fold. It also changed shapes and added new areas in the far east and west.

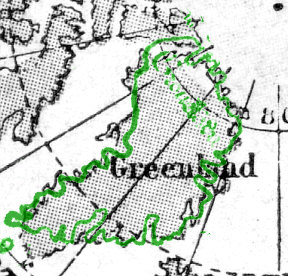

One of the most surprising things was how the Vinland Map showed Greenland. It showed Greenland as an island, with a shape and direction that were very accurate. This was strange because maps from that time, including those by Claudius Clavus in the 1420s, showed Greenland as a peninsula connected to northern Russia. Also, Greenland was not known to have been sailed around until the 20th century.

Experts also wondered if the changes in the far east were meant to show Japan. The map seemed to show not only Honshu, but also Hokkaido and Sakhalin. These islands were not even on Asian maps in the 15th century.

Language and Handwriting Clues

The Latin text on the map used a form of Leif Ericson's name ("Erissonius") that was more common in the 17th century. Also, the Latin captions used a special linked letter called a ligature (æ). This was almost never used in the late Middle Ages. While it was brought back by Italian scholars in the early 1400s, it was only found in very specific, classical-style documents, not with the Gothic writing style seen on the map.

Another clue came from a caption that mentioned Bishop Eirik of Greenland "and neighboring regions." This exact phrase was only known from the work of a religious scholar named Luka Jelić, who lived from 1864 to 1922. It seemed that either Jelić had seen the map and kept it secret, or the map's creator had copied Jelić's phrase.

Handwriting experts at the 1966 conference also disagreed that the map's captions were written by the same person as the other texts. The British Museum had rejected the map in 1957 because their experts saw handwriting styles that did not appear until the 1800s.

Parchment Dating and Ink Tests

Radiocarbon dating of the parchment (animal skin used for writing) in 1995 showed it was from between 1423 and 1445. However, there was a strange substance found all over the map. This substance turned out to be tiny traces of fallout from 1950s nuclear tests. While this fallout was not on top of the ink, it raised questions about when the ink was actually applied.

In 2008, a theory was published that tried to explain how the ink could be medieval. But other experts showed that this theory was based on a misunderstanding of the chemical tests.

Later Investigations

In 2004, Kirsten A. Seaver published a book called Maps, Myths, and Men: The Story of the Vinland Map. She reviewed all the arguments and evidence. She was praised for her detailed study. She also thought that a cartographer named Father Josef Fischer might have been the forger. However, later research showed that the map was unlikely to have been with Fischer. A handwriting expert also said that Fischer's writing did not match the map.

From 2005 to 2009, a team from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts studied the map. They confirmed that the two halves of the map were separate. One idea was that a forger might have found two blank pages in an old book and joined them. The Danish team later said their tests showed "no signs of forgery." However, their work did not look at some of the earlier findings, like the specific type of chemicals in the ink.

New Discoveries in 2018

In 2013, a Scottish researcher named John Paul Floyd found two references from before 1957 to the old books that came with the Vinland Map. One reference was from an exhibition in Madrid in 1892-93. It listed a 15th-century book that included the Speculum Historiale and Historia Tartarorum. Neither of these old descriptions mentioned a map. It is known that Enzo Ferrajoli, who sold the Vinland manuscript in 1957, was convicted of stealing manuscripts from a church library in Spain in the 1950s.

Floyd also noticed that the person who made the Vinland Map seemed to have used an 18th-century copy of the 1436 Bianco map. The Vinland Map copied several mistakes from this 18th-century copy. This was strong proof that the map was not real. Floyd published his findings in a book in 2018.

Confirmed as a Forgery (2018)

For many years, Yale University did not say if they thought the map was real or fake. In 2002, a Yale librarian said they were just "custodians of an extremely interesting and controversial document." However, in 2011, a Yale history professor said he believed the map was "unfortunately a fake."

At a conference in 2018, a Yale scientist named Richard Hark shared new chemical test results. These tests showed that the ink lines on the map contained different amounts of a substance called anatase. This type of anatase is found in modern, manufactured products. The same substance was also found on two small spots on the first page of the Tartar Relation, where old ink seemed to have been erased and new ink put in its place.

Raymond Clemens, a curator at Yale's Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, said that the latest research proves "beyond a doubt" that the Vinland Map "was a forgery, not a medieval product." In a 2019 article, Clemens explained that John Paul Floyd's research showed the Vinland Map was based on a printed copy of Bianco's map made in 1782, not the original 1436 map. This was because the Vinland Map copied mistakes from the 1782 copy that were found nowhere else. New technology at the Beinecke Library also helped confirm that the map was "clearly a 20th century fake."

Further Information

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine:

See also

In Spanish: Mapa de Vinlandia para niños

In Spanish: Mapa de Vinlandia para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |