Industrial Revolution in Scotland facts for kids

The Industrial Revolution in Scotland was a huge change that happened between the mid-1700s and the late 1800s. It transformed how things were made and how the economy worked. Before this, Scotland joined with England in 1707, creating Great Britain. This union was meant to open up bigger markets in England and the growing British Empire. At first, the economic benefits were slow to appear. However, trade in things like linen and cattle with England grew. Glasgow became very important due to the tobacco trade, and merchants there started investing in many new businesses like textiles and iron. This laid the groundwork for Glasgow to become a major industrial city after 1815.

The linen industry was Scotland's most important business in the 1700s. It helped set the stage for later industries like cotton, jute, and wool. Scottish banks also played a big part in the fast growth of the economy in the 1800s. Cotton spinning and weaving became a leading industry in the west of Scotland. But when raw cotton supplies were cut off during the American Civil War in 1861, Scotland shifted to engineering, shipbuilding, and making locomotives. Steel began to replace iron after 1870. This made Scotland a global leader in these heavy industries.

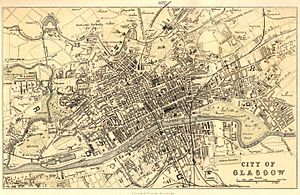

By 1800, Scotland was already one of the most urbanized places in Europe. Glasgow grew into one of the world's largest cities, known as "the Second City of the Empire" after London. Dundee also became a key industrial and trading hub. However, this rapid growth caused problems. Housing, town planning, and public health couldn't keep up. Living conditions in some cities were very poor, with overcrowding, high infant death rates, and a lot of tuberculosis. Even with new jobs, there weren't enough good ones for everyone. Because of this, about two million Scots moved to North America and Australia between 1841 and 1931. Another 750,000 Scots moved to England. Today, there are about as many people of Scottish descent in Canada and America as there are people living in Scotland.

Contents

Why Scotland Changed: The Industrial Revolution Begins

By the early 1700s, Scotland wanted to join with England. This was because it promised access to bigger markets in England and the growing British Empire. On January 6, 1707, the Scottish parliament voted to accept the Treaty of Union. This agreement created a full economic union. Most of its 25 articles were about how the new state, "Great Britain," would handle money and trade. Scotland gained 45 members in the British House of Commons and 16 in the House of Lords. The Scottish parliament ended, and London took over laws for currency, taxes, and trade. At the time, England had about five times more people and 36 times more wealth than Scotland.

Many things helped Scotland industrialize. These included a large supply of cheap workers, natural resources like coal and iron, and new technologies like the steam engine. There were also markets ready to buy Scottish products. Better transport links, a strong banking system, and new ideas about economic growth from the Scottish Enlightenment also helped a lot.

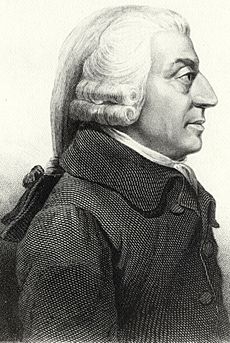

New Ideas: The Scottish Enlightenment

In the 1700s, the Scottish Enlightenment made Scotland a leader in new ideas in Europe. This period focused on everything from intellectual and economic matters to science. Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations, which was the first book on modern economics. It quickly changed British economic policy and still influences talks about globalisation and tariffs today. Important scientific discoveries were made by people like William Cullen (a doctor and chemist), Joseph Black (a physicist and chemist), and James Hutton (the first modern geologist). Even after the 1700s, Scots like James Watt (who improved the steam engine) and Lord Kelvin (a famous physicist) continued to make huge contributions to science.

Farming Changes: The Agricultural Revolution

After Scotland joined England in 1707, rich landowners tried to improve farming. The Society of Improvers was started in 1723, with 300 members including dukes and landlords. At first, these changes were limited to certain farms. But the idea of improving farming spread. New crops like hay, turnips, and cabbages were introduced. Lands were fenced off, marshes were drained, and new roads were built. Farmers started using new methods like crop rotation. The potato arrived in Scotland in 1739, which greatly improved the food available for poor farmers.

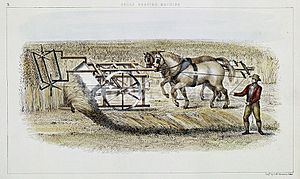

Fencing off land meant that the old "runrig" system, where land was shared, was replaced. This led to more specialized farming. For example, the Lothians became a major area for growing grain, while Ayrshire focused on cattle. Although some landowners helped their displaced workers, the Agricultural Revolution also caused the Lowland Clearances. This is when thousands of farmers were forced to leave the lands their families had lived on for hundreds of years. Improvements continued in the 1800s, including the first working reaping machine by Patrick Bell in 1828. These farming changes meant Scotland could feed its growing population and freed up workers for new factories.

Banking: Helping the Economy Grow

Scotland's first banks were the Bank of Scotland (1695) and the Royal Bank of Scotland (1727). Glasgow soon had its own banks, like "the Ship Bank" in 1749. By the end of the 1700s, Scotland had a thriving financial system. There were over 400 bank branches, which was double the number in England compared to the population. Scottish banks had fewer rules than English ones. Many historians believe that Scotland's flexible banking system greatly helped the economy grow quickly in the 1800s. The British Linen Company, started in 1746, began by making linen but slowly became a bank, lending money to other linen makers.

Better Transport: Moving Goods and People

Scotland's long coastline meant that most places were close to sea transport, especially the central area where industry would grow. Before the 1700s, most roads were just poor dirt tracks. In the late 1700s, roads improved with the help of turnpike trusts (who charged tolls) and new military roads. Canals also became important. Four major canals in the Lowlands – the Forth and Clyde, Union, Monkland, and Crinan – carried thousands of passengers and tons of goods by the early 1800s.

Exports: Trading with the World

When tariffs (taxes on imports) with England were removed, Scottish merchants had a huge chance to trade, especially with Colonial America. However, the economic benefits of the union appeared very slowly at first. Scotland was too poor to fully use the opportunities of the bigger free market. In 1750, Scotland was still a poor, rural farming society with 1.3 million people. The disastrous Darien scheme (a failed attempt to set up a colony) had also hurt Scotland's economy badly.

Some progress was seen, like selling linen and cattle to England. Money also came from Scots serving in the military. The tobacco trade, which Glasgow dominated after 1740, became very profitable. Glasgow's "Tobacco Lords" had the fastest ships sailing to Virginia. This trade had started as smuggling but became legal after the 1707 Act of Union. Merchants who made money from American trade began investing in many new businesses: leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, and more. This set the stage for Glasgow to become a leading industrial center after 1815. The tobacco trade stopped during the American Revolution (1776–1783) when supplies were cut off. But trade with the West Indies (Caribbean islands) grew, making up for the loss. This was due to the growing cotton industry and demand for sugar. Other towns like Greenock also benefited, expanding their ports and trading sugar and rum.

Linen: Scotland's First Big Industry

Making linen was Scotland's most important industry in the 1700s. It laid the foundation for later industries like cotton, jute, and wool. The Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland guided Scottish industrial policy. They wanted to build an economy that worked with England's, not against it. Since England had a strong wool industry, Scotland focused on linen. Scottish politicians managed to stop a tax on linen exports, and from 1727, the industry received government money. This led to a big increase in trade. Paisley became a major center for linen production, using Dutch methods. Glasgow made linen for export, and its trade doubled between 1725 and 1738.

The Board of Trustees encouraged and supported merchant entrepreneurs. This helped them compete with German products and increase Scotland's share of the linen market, especially in the American colonies. The British Linen Company, founded in 1746, was the largest linen firm in Scotland. In 1728, 2.2 million yards of linen cloth were produced. By 1730, linen had already replaced wool as the main manufacturing industry. Production reached 7.6 million yards by 1750 and peaked at 12.1 million yards in 1775. However, there were also sharp downturns. It was mostly a rural industry, with most work done in homes rather than factories. About 100,000 people worked in it, with four out of five being women who spun the flax. Men operated the looms.

The government promoted linen use from the late 1600s. A 1686 law said all Scots had to be buried in Scottish-made linen. In 1748, a ban on French cambric (a type of fine linen) further boosted the industry. By 1770, Glasgow was the biggest linen manufacturer in Britain. In 1787, Calton, Glasgow saw Scotland's first industrial strike when 7,000 weavers protested a 25% wage cut. Soldiers were sent in, and three people were killed. To stay competitive, Glasgow manufacturers later switched to fine cotton muslin, which became very popular.

The 1800s: Heavy Industry Takes Over

Scotland's economy, which had long relied on farming, started to industrialize after 1790. At first, the main industry in the west was cotton production. But after 1861, when the American Civil War cut off raw cotton supplies, Scotland shifted to engineering, shipbuilding, and making locomotives. Steel began to replace iron after 1870.

Cotton: A Fast-Growing Industry

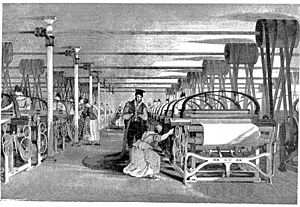

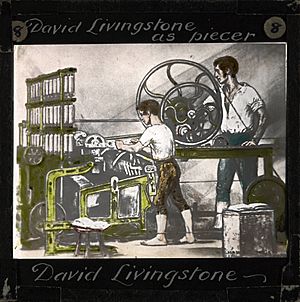

From about 1790, textiles became the most important industry in western Scotland, especially cotton spinning and weaving. The first cotton spinning mill opened in Penicuik in 1778. By 1787, Scotland had 19 mills, and by 1839, there were 192. Cotton grew quickly because the price of raw cotton, mostly imported from the US, fell sharply due to slavery. Also, there was a large supply of cheap workers because of population growth and migration. In 1775, 137,000 pounds of raw cotton were imported into the Clyde area. By 1812, this had increased eight times to over 11 million pounds. The money invested in the industry grew sevenfold between 1790 and 1840.

By 1800, cotton was the main industry in the Glasgow area. The New Lanark mills were the largest in the world at that time. Early production was helped by new machines like the spinning mule and water frame, and by water power. Steam-powered machines were introduced from 1782. However, only about a third of workers were in factories. The industry still relied heavily on hand loom weavers working from their homes. In 1790, about 10,000 weavers worked in cotton. By 1800, it was 50,000. The cotton industry thrived until 1861, when the American Civil War stopped the supply of raw cotton. The industry never fully recovered. But by then, Scotland had developed heavy industries based on its coal and iron.

Coal: Fueling the Revolution

Coal mining became a huge industry and continued to grow into the 1900s. It provided fuel to melt iron, heat homes and factories, and power steam engines, locomotives, and steamships. Coal mining grew rapidly in the 1700s, reaching 700,000 tons a year by 1750. Most coal was found in five areas across the Central Belt. The first Newcomen Steam Engine was used in a Scottish coal mine in 1719. But water power remained the most important power source for most of the century.

With more people living in cities and the demands of new heavy industry, coal production grew from about 1 million tons a year in 1775 to 3 million by 1830. Production almost doubled by the 1840s and peaked in 1914 at about 42 million tons a year. At first, more production was possible due to cheap labor, especially from Irish immigrants starting in the 1830s. Then, mining methods changed. Blasting powder was introduced in the 1850s, and machines were used to bring coal to the surface. Steam power was introduced in the 1870s. Landowners were replaced by companies focused on profit. By 1914, there were a million coal miners in Scotland.

Iron and Steel: Building the Future

The invention of James Beaumont Neilson's hot blast process for melting iron in 1828 completely changed the Scottish iron industry. It allowed the abundant native blackstone iron ore to be melted with ordinary coal. In 1830, Scotland had 27 iron furnaces. By 1840, it had 70, and by 1860, it peaked at 171. In 1857, Scotland produced over 2,500,000 tons of iron ore, which was 6.5% of the UK's total. Production of pig iron (raw iron) rose from 797,000 tons in 1854 to a peak of 1,206,000 in 1869.

As a result, Scotland became a center for engineering, shipbuilding, and making locomotives. By the 1871 census, the number of workers in heavy industry in the Strathclyde region was higher than in textiles. By 1891, heavy industry employed most people in the country. Towards the end of the 1800s, steel production largely replaced iron production.

Railways: Connecting Scotland

Britain was a world leader in building railways, which helped expand trade and coal supplies. The first successful train line in Scotland, between Monkland and Kirkintilloch, opened in 1826. By the late 1830s, there was a network of railways, including lines between Dundee and Arbroath, and connecting Glasgow, Paisley, and Ayr. The line between Glasgow and Edinburgh, mainly for passengers, opened in 1842 and was very successful. By the mid-1840s, there was a "railway mania" as many new lines were built. A good passenger service was set up by the late 1840s. A network of freight lines reduced the cost of shipping coal, making Scottish products competitive across Britain. The North British Railway was formed in 1844 to link Edinburgh and eastern Scotland with Newcastle. The next year, the Caledonian Railway began connecting Glasgow and the west to Carlisle. It took until the 1870s to complete a dense railway network in the Lowlands with connections to England. By the 1860s, five main companies operated 98% of the system. The money invested in Scottish railways was £26.6 million in 1859, reaching £166.1 million by 1900. Railways cut travel time between Edinburgh or Glasgow and London from 43 hours to 17, and by the 1880s, it was down to 8 hours. Railways also opened the London market to Scottish beef and milk, helping the Aberdeen Angus cattle breed become famous worldwide.

Shipbuilding: "Clyde-built" Quality

Shipbuilding on Clydeside (the River Clyde through Glasgow) began when the first small shipyards opened in 1712 at Greenock. Major firms included Denny of Dumbarton and Fairfield of Govan. Equally important were the engineering firms that supplied the engines, boilers, and steering gear for these ships. The Vulcan works, owned by Robert Napier and Sons, were the first to start making large iron passenger ships in the 1840s.

In 1835, the Clyde produced only 5% of the ship tonnage built in Britain. The change from wooden to iron ships was gradual. Wooden ships were cheaper to build until around 1850. Even later, ships like the famous clipper Cutty Sark, launched from Dumbarton in 1869, had composite hulls (wood and iron). The change from iron to steel shipbuilding was also slow due to cost. As late as 1879, only 18,000 tons of steel-built shipping were launched on the Clyde, which was 10% of all tonnage. Similarly, ships changed from sail to steam, and then to the more efficient steam turbine engine, which became common in the mid-1880s. Ship tonnage increased more than six times between 1880 and 1914. Production peaked during the First World War, and the term "Clyde-built" became known for high industrial quality.

Engineering Architecture: Impressive Structures

The 1800s saw some major engineering projects. These included Thomas Telford's stone Dean Bridge (1829–31) and iron Craigellachie Bridge (1812–14). In the 1850s, new ways of building with wrought iron and cast-iron were used for commercial warehouses in Glasgow.

The most important engineering project was the Forth Bridge. This was a huge cantilever bridge for trains over the Firth of Forth, west of Edinburgh. Construction of an earlier design was stopped after another bridge by the same engineer, the Tay Rail Bridge, collapsed in 1847. The project was taken over by John Fowler and Benjamin Baker. They designed a new structure, which was built by a Glasgow company from 1883. It opened on March 4, 1890, and spans over 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles). It was the first major structure in Britain to be built of steel.

Impact of the Industrial Revolution

Population Growth and City Life

In 1755, Scotland had 1,265,380 people. By the first official census in 1801, the population was 1,608,420. It grew steadily in the 1800s, reaching 2,889,000 in 1851 and 4,472,000 in 1901. While some rural areas lost people due to farming changes, towns grew rapidly. Aberdeen, Dundee, and Glasgow all grew by a third or more between 1755 and 1775. The textile town of Paisley more than doubled its population. Scotland was already one of the most urbanized societies in Europe by 1800. In 1800, 17% of Scots lived in towns with over 10,000 people. By 1850, it was 32%, and by 1900, it was 50%. By 1900, one in three Scots lived in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, or Aberdeen.

Glasgow became the largest city. Its population was 43,000 in 1780, reaching 147,000 by 1820, and 762,000 by 1901. This growth was due to a high birth rate and people moving in from the countryside and especially from Ireland. Glasgow was now one of the largest cities in the world, known as "the Second City of the Empire" after London.

Dundee improved its harbor and became an industrial and trading center. Dundee's industry was based on "the three Js": jute, jam, and journalism. East-central Scotland became very reliant on linen, hemp, and jute. Even with ups and downs in trade, profits were good in the 1800s. These profits helped make Dundee an important source of overseas investment, especially in North America.

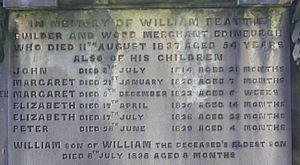

The rapid industrial growth brought work and wealth, but housing, city planning, and public health couldn't keep up. For a time, living conditions in some towns and cities were very bad. There was overcrowding, high infant death rates, and increasing rates of tuberculosis. Death rates were higher in Scotland than in England and other European countries. They were much higher in cities than in rural areas. Death rates probably peaked in Glasgow in the 1840s, when many people moved in from the Highlands and Ireland. The city's sanitation couldn't handle the large population, leading to outbreaks of diseases. National death rates began to fall in the 1870s, especially in cities, as conditions improved. Some companies built inexpensive housing for workers, which was much better than the inner-city slums. This led many factory owners to support government housing programs and self-help projects for working-class families.

New Social Classes: Workers and Their Rights

One result of industrialization and city growth was the rise of a distinct skilled working class. This group developed a strong sense of identity before the 1820s. Cotton workers, in particular, were involved in many protests. This led to the Radical War of 1820, where three weavers declared a temporary government, and Glasgow cotton workers went on strike. The conflict ended with government soldiers charging at Bonnymuir. This discouraged direct political action by workers, but they continued to push for reform through movements like Chartism.

From the 1830s, the political power of working classes grew as more people gained the right to vote, and trade unions became stronger. Before the 1832 Reform Act, fewer than 5,000 people could vote in Scotland. The 1832 Act allowed middle-class businessmen to vote. The 1868 Act included skilled workers, and the 1884 Act allowed many farm workers, miners, and unskilled men to vote. These changes were supported by trade unions, which grew from the mid-1800s. Miners, in particular, fought for better wages and conditions. Scottish trade unions in the 1800s were often small and local. However, new unions in the late 1800s, like those for dockers and railwaymen, built regional and national support networks.

Women in the Workforce

Industrialization greatly changed the roles of women in Scotland. Women and girls made up a much larger part of the workforce than in other parts of Britain. They were the majority of workers in some industries. The growth of flax spinning and the linen industry in the 1700s relied almost entirely on female labor. The same was true for the sewed muslin industry in western Scotland later in the century. When flax spinning became mechanized, there were 280 women for every 100 men, the highest proportion of women in the UK.

In Dundee in the 1840s, while male employment increased by 1.6 times, female employment went up by 2.5 times. This made Dundee the only large town in Scotland where most women had paid jobs. In the cotton industry in the 1800s, women and girls made up 61% of the workforce in Scottish mills, compared to 50% in Lancashire, England. Although most women worked in textiles, they were also a significant part of the workforce in other areas. For example, 12% of underground miners were women in Scotland, compared to 4% in Britain overall. The new opportunities for women, and the extra money they brought into the household, likely helped improve living standards for working-class families.

The role of women in the workforce peaked in the 1830s. As heavy industry became more dominant, there were fewer opportunities for women. From the mid-1800s, a series of laws limited women's roles in industry. The Mines Regulation Act of 1842 stopped women from working underground. This put 2,500 women out of work in eastern Scotland, causing real hardship because their income was vital to their families. This was followed by factory acts that placed restrictions on women's employment. Many of these laws were pushed by trade unions trying to secure better wages for their male members. Women had little involvement in official trade unions for much of this period. However, they were often involved in unofficial strikes. The first recorded strike involving women was in 1768, and there were 300 known strikes involving women between 1850 and 1914. Towards the end of the century, there were growing efforts to unionize women. The Scottish Women's Trade Council (SWTC) was formed in 1887.

Migration: Scots Moving Around the World

The growth of industry led to many workers arriving from Ireland, who moved into factories and mines in the 1830s and 1840s. Many were seasonal workers who helped build docks, canals, and railways. By the 1840s, an estimated 60-70% of coal miners in Lanarkshire were Irish. More Irish immigrants arrived during the Great Famine of 1845. By the 1841 census, 126,321 people, or 4.6% of Scotland's population, were born in Ireland. Many more were of Irish descent. Most settled in western Scotland, and in Glasgow, 44,000 people (16% of the city's population) were born in Ireland. Most Irish immigrants (about three-quarters) were Catholic, which brought a big cultural and religious change to Scotland. The other quarter were Protestant, bringing groups like the Orange Order and increasing religious divisions in major cities.

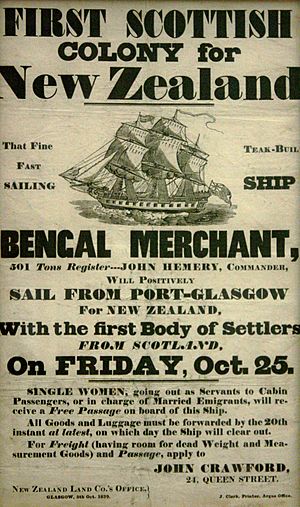

Even with industrial growth, there weren't enough good jobs. This, combined with major changes in farming, meant that between 1841 and 1931, about two million Scots moved to North America and Australia. Another 750,000 Scots moved to England. Of those who moved outside Europe before 1914, 44% went to the US, 28% to Canada, and 25% to Australia and New Zealand. Other places included the Caribbean, India, and South Africa. By the 2000s, there were about as many people of Scottish and Scottish American descent as the five million people still living in Scotland. At first, many migrants agreed to indentures, especially to the Thirteen Colonies. This meant their passage was paid for, and they were guaranteed housing and work for five or seven years. Later, agents and societies like the Salvation Army helped people, often focusing on young or female immigrants.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |