Art in early modern Scotland facts for kids

Art in early modern Scotland looks at all the different kinds of art made in Scotland from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s. This period saw the start of the Renaissance and led up to the Enlightenment. During this time, art changed a lot, especially after the Reformation.

Before the Reformation, churches in Scotland were often very colorful and fancy. They had special altars and statues. Many religious artworks, like paintings and books, came from the Netherlands. However, after the Reformation in the mid-1500s, much of this religious art was destroyed. This included almost all the old stained glass, sculptures, and paintings.

Around 1500, Scottish kings started having their portraits painted. Artists from other countries, especially the Netherlands, created some impressive works. After the Reformation, royal portrait painting really grew. King James VI hired artists like Arnold Bronckorst and Adrian Vanson to paint him and important people at his court. The first important Scottish artist was George Jamesone. After him, many other artists painted portraits as more people, like lairds (landowners) and burgesses (town leaders), wanted their pictures painted.

The Reformation meant artists lost their main customers, the churches. So, they started working for regular people instead. This led to beautiful Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls in homes. Other ways people decorated their homes included tapestries and carvings in stone and wood. In the early 1700s, art became more organized. Many artists traveled to Italy to learn. The Academy of St. Luke, a group for artists, started in 1729. Allan Ramsay, who became one of Britain's most important artists, was a member.

Contents

Religious Art in Early Scotland

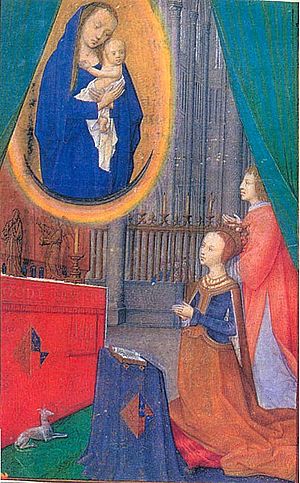

Before the Reformation, people in Scotland bought religious art from the Netherlands. This included images of saints and altarpieces. For example, King James III ordered a large altarpiece for a church in Edinburgh. Many beautiful prayer books were also made in the Netherlands and France for Scottish nobles. One famous example is the Hours of James IV of Scotland, a richly illustrated book given by King James IV to Margaret Tudor in 1503. It is considered one of the finest medieval books made for Scotland.

Inside churches, especially in the northeast, there were often highly decorated sacrament houses. These were special places to keep the bread and wine used in church services. Examples can still be seen at Kinkell (from 1524) and Deskford (from 1541). Tombs in churches were usually brightly colored and gilded. They honored church leaders, knights, and their wives. Unlike England, where metal plaques became popular, Scotland continued to make stone tombs until the end of the Middle Ages.

The Reformation caused a lot of damage to Scotland's church art. Many religious statues, paintings, and almost all medieval stained glass were destroyed. The only important stained glass that survived from before the Reformation is in the St. Magdalen Chapel in Cowgate, Edinburgh, finished in 1544. Some wood carvings can still be seen at King's College, Aberdeen and Dunblane Cathedral. In the West Highlands, where families had carved monuments for generations, the Reformation meant they lost their work. This led to a noticeable drop in the quality of gravestones made later. Some historians believe the Scottish Reformation made people prefer simpler art, focusing more on private and home life.

Painting People: Portraiture

Around 1500, Scottish kings started having their faces painted on wooden panels using oil paints. This was a way to show their power. In 1502, King James IV paid for portraits of the English royal family. An artist named Maynard Wewyck, who usually worked for the English king, then stayed in Scotland to paint King James and his new wife, Margaret Tudor. While Scottish royal portraits from this time are not as detailed as those from other parts of Europe, artists from the Netherlands, a major art center, created much more impressive works. One early example is a fine portrait of William Elphinstone, likely painted by a Scottish artist using Dutch methods.

Royal portrait painting in Scotland was often interrupted because kings were young or there were regents (people ruling for a young king). King James V was more interested in building grand buildings to show his royal power. Mary, Queen of Scots grew up in France, where famous European artists drew and painted her. However, she didn't order many adult portraits, except for one with her second husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. This might have been because Scottish nobles valued family crests or grand tombs more than portraits.

After the Reformation, portrait painting really took off. Many important people had their pictures painted, even small ones called miniatures. Artists from the Low Countries (like the Netherlands and Belgium) were still important. Hans Eworth, who had been a court painter in England, painted several Scottish people in the 1560s. He painted James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray in 1561 and later painted a portrait of the young Darnley and his brother. Lord Seton ordered two portraits in the Netherlands in the 1570s: one of himself and one of his family. A unique Scottish type of painting is the "vendetta portrait." These were made to remember a terrible event. Examples include the Darnley memorial portrait, which shows the young King James VI kneeling at his murdered father's tomb. Another is the life-size painting of the dead Bonnie Earl of Moray, which clearly shows the wounds he received when he was killed in 1592.

Around 1579, an attempt was made to create a series of portraits of Scottish kings. These were likely for the special entry of the fifteen-year-old James VI into Edinburgh. During James VI's rule, Renaissance styles of portraiture became popular. He hired two Flemish artists, Arnold Bronckorst and Adrian Vanson, who painted the king and important people at his court. However, when James VI became King of England in 1603, he moved his court to London. This meant artists in Scotland lost a major customer. As a result, nobles and local landowners became the main supporters of art.

By the 1600s, portrait painting was popular among many people, including landowners like Colin Campbell and John Napier. The first important Scottish artist was George Jamesone (1589/90-1644) from Aberdeen. He trained in the Netherlands and became a very successful portrait painter during the time of King Charles I. Jamesone taught John Michael Wright (1617–94), who painted both Scottish and English people. The Flemish-Spanish painter John Baptist Medina (1659–1710) came to Scotland in 1693 and became the leading Scottish portrait painter of his time. He trained his son, also named John, and William Aikman (1682–1731). Aikman became the top portrait painter of the next generation. He moved to London in 1723, and after this, most famous Scottish painters followed him.

Decorating Homes

When the Reformation happened, artists and craftspeople lost their church jobs. So, they started working for private citizens instead. This led to a boom in Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls. Many homes of town leaders, landowners, and nobles were decorated with detailed and colorful patterns and scenes. Over a hundred examples are known to have existed. Unnamed Scottish artists created these, using design books from Europe. These designs often included symbols about human ideas, family crests, religious beliefs, classical stories, and hidden meanings.

The oldest surviving example is at Kinneil House in West Lothian, decorated in the 1550s for James Hamilton, who was ruling for the young queen. Other examples include the ceiling at Prestongrange House, made in 1581, and the long gallery at Pinkie House, painted in 1621.

Records show that Scottish palaces also had rich tapestries. For example, tapestries showing scenes from the Iliad and Odyssey were displayed for King James IV at Holyrood. Some of these were made by professional embroiderers. However, needlework was also a common skill for women of all social classes. Some tapestries were made by noblewomen, like the bed valances made by Katherine Ruthven for her wedding in 1551. These are the oldest surviving Scottish embroideries. They show the couple's initials, family crests, and the story of Adam and Eve. A table carpet with Katherine Oliphant's initials, family crest, Bible verses, and an elephant (perhaps a play on her name) may be linked to her marriage. Much of the needlework from the 1500s has been wrongly linked to Mary, Queen of Scots. However, it is thought she did work on the Oxburgh Hangings while she was held prisoner in England.

While stone and wood carving mostly stopped in churches after the Reformation, it continued in royal palaces, grand noble homes, and even smaller homes of landowners. The detailed lid of the 14th-century Bute mazer, carved from a single piece of whale bone, was likely made in the early 1500s. At Stirling Castle, stone carvings on the royal palace from King James V's time were based on German designs. The carved oak portraits from the King's room, known as the Stirling Heads, include figures from that time, the Bible, and classical stories. These, along with the fancy Renaissance fountain at Linlithgow Palace (around 1538), suggest there was a workshop connected to the royal court in the early 1500s. King James V and later kings hired a skilled French craftsman and wood carver named Andrew Mansioun, who lived in Edinburgh and taught apprentices.

Some of the best wood carvings for homes are the Beaton panels made for Arbroath Abbey and at Huntly Castle. Huntly Castle was rebuilt for George Gordon, 1st Marquess of Huntly in the early 1600s and featured many family crests. These carvings were damaged by an army in 1640 because they were seen as having "Catholic" meanings. From the 1600s, as noble homes became more about comfort than defense, carvings were used a lot on fireplaces, family crests, and classical designs. Plasterwork also became popular, often showing flowers and angels. Richly carved decorations on ordinary houses were common. There are also carvings of royal arms, like those at Holyrood Palace, designed by the Dutch painter Jacob de Wet in 1677. Carving also continued in works like the stone panels in the garden of Edzell Castle (around 1600), carvings for Edinburgh and Glasgow universities (now lost), and the many fancy sundials of the 1600s, like those at Newbattle.

Art Becomes a Profession

The growing importance of royal art can be seen in the job of Painter and Limner, created in 1702 for George Ogilvie. This job involved painting the King, his family, and decorating royal homes. However, from 1723 to 1823, this job was just a title held by members of the Abercrombie family, who weren't necessarily artists. Many painters in the early 1700s were still mostly craftspeople. This includes the Norie family, James (1684–1757) and his sons, Robert and the younger James. They painted Scottish landscapes in noble homes. These landscapes were often capriccios (fantasy scenes) or pastiches (copies) of Italian and Dutch landscapes. They taught other artists and are known for starting the tradition of Scottish landscape painting, which became very popular later in the 1700s. Italy became a very important place for Scottish artists. Many went on the Grand Tour there to paint, see art, and learn from Italian masters.

In 1729, artists tried to start a painting school in Edinburgh called the Academy of St. Luke. It was named after a famous art academy in Rome. Its president was George Marshall, who painted still life pictures and portraits. The treasurer was the engraver Richard Cooper. Other members included Cooper's student Robert Strange, the two younger Nories, and portrait painters John Alexander (around 1690-around 1733) and Allan Ramsay (1713–84). The group's success was limited because some members were linked to Jacobitism (a movement supporting the exiled Stuart kings). For example, Strange printed banknotes for the rebels. Alexander was a great-grandson of George Jamesone.

Ramsay became the most famous student of the academy. He studied in Sweden, London, and Italy before settling in Edinburgh. There, he became a leading portrait painter for Scottish nobles. He later moved to London in 1757 but would sometimes return to Edinburgh for special painting jobs for the rich and powerful.

See Also

- Christianity in Medieval Scotland

- Scottish Reformation

- Portrait painting in Scotland

- Portrait painting

- Domestic furnishing in early modern Scotland

- Scottish castles

- Estate houses in Scotland

- Scottish Enlightenment

Images for kids

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |