Battle of Preston (1648) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Preston |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second English Civil War | |||||||

Battle of Preston 1648 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 11,000 (Not all were engaged in the battle.) | 8,600-9,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000 killed 9,000 captured |

under 100 killed | ||||||

The Battle of Preston (August 17–19, 1648) was a major fight during the Second English Civil War. It happened mostly near Walton-le-Dale and Preston in Lancashire. In this battle, the New Model Army, led by Oliver Cromwell, won a big victory. They defeated the combined forces of the Royalists and Scots, who were commanded by the Duke of Hamilton. This important win for the Parliamentarians helped bring the Second English Civil War to an end.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Battle of Preston was part of a bigger conflict called the Second English Civil War. To understand why it happened, we need to look back a bit.

King Charles I and the Scottish Church

In 1639 and 1640, King Charles I ruled both Scotland and England. He tried to change the Scottish Kirk (their church) to be more like the English church. The Scots did not agree with these changes. This disagreement led to two short wars called the Bishops' Wars. Charles I did not win these wars. The Scots then made sure their own government, the Covenanters, had more power. They also made everyone in government sign a special promise called the National Covenant.

The First English Civil War

After these wars, the relationship between King Charles I and his English Parliament also got very bad. This led to the First English Civil War in 1642. In this war, Charles's supporters, known as the Royalists, fought against the Parliamentarians and the Scots.

In 1643, the English Parliament and the Scots formed an alliance. They signed the Solemn League and Covenant. In this agreement, the English Parliament promised to make their church more like the Scottish Kirk. In return, the Scots would help them fight the King.

After four years, the Royalists lost the war. King Charles I gave himself up to the Scots in 1646. The Scots and the English Parliament then offered the King a peace deal called the Newcastle Propositions. This deal would have made everyone in England, Scotland, and Ireland sign the Solemn League and Covenant. It also would have made the churches in all three kingdoms follow the Covenant. Plus, it would have taken away much of Charles's power as King of England.

The Scots tried for months to get Charles to agree, but he refused. The English then asked the Scots to leave England since the war was over. So, in 1647, the Scots handed Charles over to the English Parliament's forces. They also received some money.

The King's Secret Deal

After this, King Charles I started talking to different groups. Some English Parliamentarians and the Scots wanted him to accept a slightly changed version of the Newcastle Propositions. But in June 1647, a soldier from the New Model Army named George Joyce took Charles. The army then tried to get him to agree to a less strict deal called the Heads of Proposals. This deal did not require the church to become Presbyterian.

However, Charles rejected this deal too. Instead, on December 26, 1647, he secretly signed an agreement with the Scottish leaders. This agreement was called the Engagement. In it, Charles agreed to make the Solemn League and Covenant official in both kingdoms. He also agreed to accept Presbyterianism in England, but only for three years. In return, the Scots would help him get his throne back in England.

Scots Divided

When the Scottish leaders returned to Edinburgh with the Engagement, the Scots were very divided. Those who supported the deal were called the Engagers. They believed it was the best chance to get the Covenant accepted in all three kingdoms. They worried that if they refused, Charles might accept the English army's deal instead.

But others strongly opposed it. They thought sending an army into England for the King would break the Solemn League and Covenant. They also felt it didn't guarantee a lasting Presbyterian church in England. The Scottish Church even said the Engagement broke God's law.

After a long political fight, the Engagers gained control of the Scottish Parliament. By this time, war had started again in England between the Royalists and Parliamentarians. So, the Scots sent an army, led by the Duke of Hamilton, into England to fight for the King.

The Military Campaign

On July 8, 1648, the Scottish Engager army crossed the border to help the English Royalists. At this time, the Parliamentarian forces were busy. Cromwell was fighting at Pembroke in South Wales. Fairfax was at Colchester in Essex. Colonel Edward Rossiter was at Pontefract and Scarborough in the north.

Pembroke fell to Cromwell on July 11, and Colchester fell on August 28. Even though other rebellions were mostly put down, the war was still active. Charles, the Prince of Wales, was sailing along the Essex coast with the fleet.

Commanders and Challenges

Oliver Cromwell and John Lambert worked well together. But the Scottish commanders argued among themselves and with Sir Marmaduke Langdale, the English Royalist leader in the northwest.

The Scottish Engager army was not as strong as it used to be. Many experienced officers and soldiers, including David Leslie, refused to serve because the Scottish Church did not approve of the Engagement. The Duke of Hamilton was not as good a leader as Leslie. Also, Hamilton's army was poorly supplied. As soon as they entered England, they had to steal food from the countryside just to survive.

Army Movements

By July 8, the Scots, with Langdale's soldiers in front, were near Carlisle. They were waiting for more troops from Ulster. Lambert's cavalry was spread out at Penrith, Hexham, and Newcastle. His forces were too small to fight directly, so he used clever movements to gain time.

Appleby Castle surrendered to the Scots on July 31. Lambert, who was still following the Scottish army, moved back from Barnard Castle to Richmond. This blocked the Scots from marching on Pontefract through Wensleydale. Langdale's cavalry tried hard to move Lambert, but they couldn't get past his strong cavalry screen.

Meanwhile, Cromwell had taken Pembroke Castle on July 11. He then marched his tired, unpaid, and shoeless men quickly through the Midlands. Rain and storms slowed him down, but he knew Hamilton's army in Westmorland was in even worse shape. Cromwell received new shoes and stockings in Nottingham. He also gathered local soldiers as he went. He reached Doncaster on August 8, much faster than he expected. He then got artillery from Hull and exchanged his local soldiers for regular troops. After this, he set off to meet Lambert.

By August 12, Cromwell was at Wetherby. Lambert was at Otley with his cavalry and foot soldiers. Langdale was at Skipton and Gargrave. Hamilton was at Lancaster. Sir George Monro was at Hornby with the Scots from Ulster and the Carlisle Royalists.

On August 13, while Cromwell was marching to join Lambert, the Scottish leaders were still arguing. They couldn't decide whether to go to Pontefract or continue through Lancashire to meet other Royalists.

The Battle Itself

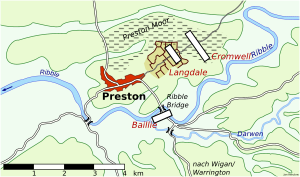

On August 14, 1648, Cromwell and Lambert were at Skipton. On August 15, they were at Gisburn. By August 16, they marched down the Ribble valley towards Preston. They knew exactly where the enemy was and planned to attack.

Forces Involved

Cromwell's army included soldiers from the main army and local militias from Yorkshire, Durham, Northumberland, and Lancashire. They were slightly outnumbered, with about 8,600 men against Hamilton's 9,000. However, Hamilton's forces were spread out along the road from Lancaster, through Preston, towards Wigan. This was done to make it easier to get supplies. Langdale's group, which was supposed to be the advanced guard, ended up guarding the left side of the army.

The First Attack

On the night of August 13, Langdale gathered his soldiers near Longridge. It's not clear if he told Hamilton about Cromwell's approach. But if he did, Hamilton ignored it. On August 17, Monro's forces were half a day's march to the north. Langdale was east of Preston. The main Scottish army was stretched out on the road to Wigan. Major-General William Baillie and his foot soldiers were still in Preston, at the very back of the column.

Hamilton, pushed by his second-in-command, James Livingston, 1st Earl of Callendar, sent Baillie's men across the Ribble to follow the main army. Just then, Langdale, with only 3,000 foot soldiers and 500 cavalry, met the first attack from Cromwell's army on Preston Moor.

The Fight and Retreat

Hamilton, like King Charles at the Battle of Edgehill, watched the Battle of Preston without really leading it. Langdale's men fought very bravely for four hours. But eventually, they were pushed back to the River Ribble.

Baillie tried to protect the bridges over the Ribble and Darwen rivers on the Wigan road. But Cromwell's forces managed to cross both bridges before nightfall. Cromwell's army immediately started chasing the Scots. They did not stop until Hamilton's army was driven through Wigan and Winwick to Uttoxeter and Ashbourne.

There, Cromwell's cavalry pressed them hard from behind. Local militias from the Midlands blocked them from the front. The remaining Scottish soldiers finally gave up on August 25.

Aftermath

The Battle of Preston was a huge blow to the Royalist hopes in the Second Civil War. Cromwell estimated that the Royalists lost 2,000 killed and 9,000 captured. Many of the captured soldiers who had joined voluntarily were sent overseas to work in other countries, like the New World or Venice. When the English Parliament celebrated the victory, they announced that Cromwell's army had lost "one hundred at the most" killed.