Battle of Edgehill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Edgehill |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

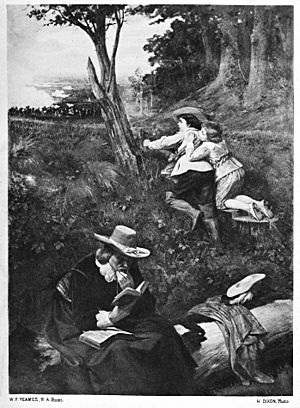

The Prince of Wales and the Duke of York sheltering during the Battle of Edgehill |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Charles I |

Earl of Essex Lord Feilding |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 500 killed 1,500 wounded |

500 killed 1,500 wounded |

||||||

The Battle of Edgehill was a major fight in the First English Civil War. It happened near Edge Hill and Kineton in southern Warwickshire, England. The date was Sunday, October 23, 1642. This battle was the first big clash between the King's army and Parliament's army.

Before the battle, King Charles I and Parliament could not agree on how to run the country. Both sides decided to raise large armies to settle their differences by force. In October 1642, the King's army was near Shrewsbury. He decided to march towards London to try and win the war quickly. Parliament's main army, led by the Earl of Essex, followed him.

On October 22, both armies found out they were very close to each other. The next day, the King's Royalist army moved down from Edge Hill to start the fight. After Parliament's cannons fired first, the Royalists attacked. Most soldiers on both sides were new to fighting and some did not have good equipment. Many soldiers ran away or stopped to steal from the enemy. Because of this, neither side won a clear victory.

After the battle, the King continued his march to London. But he was not strong enough to defeat the city's defenders before Essex's army arrived to help. The Battle of Edgehill did not end the war quickly. Instead, it showed that the war would be long and hard, lasting for four more years.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

When King Charles I realized he could not agree with Parliament, he left London in March 1642. He went to the north of England. Both Parliament and the King knew a war was coming. They started to gather their forces. Parliament passed a law called the Militia Ordinance. This law gave Parliament control over the country's trained soldiers, called trained bands.

From his temporary base in York, King Charles disagreed with Parliament's demands. He ordered his own officers to raise armies for him. The King then tried to take the port of Kingston-upon-Hull. This port held many weapons and supplies. But the Parliamentarian soldiers there stopped the King's forces.

In August, the King moved south to Lincoln and Leicester. He took weapons from their local armories. On August 22, he officially declared war on Parliament by raising his royal flag in Nottingham. Few people in the Midlands supported the King. So, after getting more weapons, Charles moved to Chester and then Shrewsbury. He expected many new soldiers from Wales and the Welsh border to join him there.

Parliament sent its army north under the Earl of Essex to face the King. Essex first went to Northampton, where he gathered almost 20,000 men. When he learned the King moved west, Essex marched towards Worcester. On September 23, there was a small fight near Worcester. The King's cavalry, led by Prince Rupert of the Rhine, defeated some of Essex's cavalry. But the King's army did not have enough foot soldiers, so they left Worcester.

Getting Ready for Battle

By early October, the King's army was almost ready at Shrewsbury. The King held a meeting with his military leaders. They discussed two plans. One was to attack Essex's army at Worcester. But the land there was difficult for the King's strong cavalry. The second plan, which they chose, was to march towards London. The King wanted to force a battle with Essex, but on his own terms.

So, the King's army left Shrewsbury on October 12. They had a two-day head start on Essex's army. They moved south-east. Essex followed, but neither army knew exactly where the other was.

By October 22, the Royalist army was staying in villages near Edgcote. They were getting close to Parliament's soldiers at Banbury. The soldiers in Banbury sent messages asking for help from Warwick Castle. Essex, who had just arrived there, ordered his army to march quickly to Kineton to help Banbury. His army was spread out, and not all his soldiers were there yet.

That evening, there were small fights between soldiers from both sides in Kineton and nearby villages. The Royalists then realized Essex's army was very close. The King ordered his army to gather for battle on top of the Edge Hill the next day.

Essex had planned to go straight to Banbury. But around 8 a.m. on October 23, his scouts reported that the Royalists were gathered on Edge Hill, about 7 kilometers (4.5 miles) from Kineton. Essex lined up his army about halfway between Kineton and the Royalist army. This spot had hedges that made a good defensive position.

Before the battle, a famous prayer was said by Jacob Astley, a Royalist commander.

Who Fought?

The two armies had some important differences. These differences affected how the battle went. Most soldiers on both sides were very new to fighting. However, they had several experienced officers. These officers had fought in the Thirty Years' War in places like the Dutch Republic or Sweden. Both the King and Parliament wanted these skilled officers to lead their armies.

The King's cavalry (soldiers on horseback) was better than Parliament's cavalry at this time. Oliver Cromwell, who arrived too late for the battle, later said that Parliament's horsemen were mostly "old servants and bar workers." He said the Royalist horsemen were "gentlemen's sons" and "persons of quality." This meant the Royalist cavalry were more used to riding and fighting on horseback. Also, Parliament's cavalry were trained to fire pistols from their horses. But the Royalist cavalry, led by Prince Rupert, would charge with swords, using their speed and weight to break enemy lines.

However, Parliament's foot soldiers were better equipped than the Royalists. The Royalist pikemen (soldiers with long spears) often lacked armor. Their musketeers (soldiers with guns) often did not have swords. This made the Royalist foot soldiers more vulnerable in close combat. Several hundred of them had only clubs or makeshift weapons.

How the Armies Lined Up

Royalist Army Positions

- The Royalist right side of cavalry and dragoons (soldiers who rode horses but fought on foot) was led by Prince Rupert. Sir John Byron supported him.

- The King's own special cavalry guard insisted on joining Rupert's front line. This left the King with no cavalry to keep in reserve.

- The center of the army had five groups of foot soldiers. There was a last-minute change in command. Lord Lindsey, the main commander, wanted to arrange them in a "Dutch" style, which was simple lines eight soldiers deep. He was upset when his idea was rejected. So, he gave up his command and fought with his own soldiers.

- Patrick Ruthven took over. He arranged the foot soldiers in a "Swedish" style, like a checkerboard. This was more effective but harder to control with new soldiers. Sergeant Major General Jacob Astley led the center in battle.

- The left side had horsemen led by Sir Henry Wilmot. Lord Digby, the King's secretary, supported him. Colonel Arthur Aston's dragoons were on the far left.

Parliamentarian Army Positions

- The Parliamentarian left side had a group of twenty cavalry troops led by Sir James Ramsay. They were supported by 600 musketeers and several cannons, hidden behind a hedge.

- In the center, Sir John Meldrum's foot soldiers were on the left of the front line. Colonel Charles Essex's soldiers were on the right. Sir Thomas Ballard's foot soldiers were behind Meldrum.

- Cavalry regiments led by Sir William Balfour and Sir Philip Stapleton were behind Charles Essex's group. These two cavalry groups would play an important role.

- A group of foot soldiers under Colonel William Fairfax connected the center to the right side.

- The right side had cavalry led by Lord Feilding. They were on higher ground, with two groups of dragoons helping them.

The Battle Begins!

Essex did not seem to want to attack first. So, the Royalists began to move down the slope of Edge Hill after midday. Even after they finished this move around 2 p.m., the battle did not start right away. It seems the sight of the King riding among his soldiers, encouraging them, made the Parliamentarians finally open fire.

The King's group moved out of range, and then an artillery duel began. The Royalist cannons were not very effective. Most of them were too high up the slope, so their shots often hit the ground harmlessly. While the cannons fired, the Royalist dragoons moved forward on both sides. They pushed back the Parliamentarian dragoons and musketeers who were protecting their cavalry.

On the right side, Prince Rupert ordered his cavalry to attack. As they charged, a group of Parliamentarian horsemen suddenly switched sides. The rest of Ramsay's cavalry fired their pistols weakly and then ran away. Rupert's and Byron's horsemen quickly rode over the Parliamentarian cannons and musketeers on that side. They happily chased Ramsay's fleeing men, which was bad for the Royalist foot soldiers who were left behind.

Wilmot charged at about the same time on the other side. Feilding's soldiers, who were outnumbered, quickly gave way. Wilmot and Digby also chased them all the way to Kineton. There, the Royalist horsemen stopped to steal from the Parliamentarian baggage. Sir Charles Lucas and William Villiers Lord Grandison gathered about 200 men. But when they tried to attack the Parliamentarian rear, they were distracted by soldiers running away from Charles Essex's defeated group.

The Royalist foot soldiers also moved forward in the center under Ruthven. Many Parliamentarian foot soldiers had already run away when their cavalry disappeared. Others fled when the fighting got close. However, the groups led by Sir Thomas Ballard and Sir John Meldrum stood their ground. The Parliamentarian cavalry regiments of Stapleton and Balfour rode through gaps in their own foot soldiers. They then charged the Royalist foot soldiers. Since there was no Royalist cavalry to stop them, they made many Royalist units run away.

The King had no strong reserve force left. As his center began to break, he ordered one of his officers to take his sons, Charles (the Prince of Wales) and James (the Duke of York), to safety. Meanwhile, Ruthven tried to rally his foot soldiers. Some of Balfour's men charged so far into the Royalist lines that they threatened the princes' guards. They even briefly took over the Royalist cannons before pulling back. In the front lines, Lord Lindsey was badly hurt and died. Sir Edmund Verney died defending the Royal Standard (the King's flag), which was captured by Parliamentarian Ensign Arthur Young.

By this time, some of the Royalist horsemen had gathered again and were returning from Kineton. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Welch, from Wilmot's Horse, got the Royal Standard back using a trick. He also captured two Parliamentarian cannons. As it started to get dark, the battle ended with shooting from both sides of a ditch. Nightfall finally stopped the fighting. The Royalists had been pushed back to where they started, but they had regrouped.

What Happened Next?

By the next morning, the King and his army went back to the Edge Hill slope. Essex's army returned to Kineton. It was a very cold night with a hard frost. People at the time thought this cold helped many wounded soldiers survive. The cold helped their wounds stop bleeding and prevented infections.

The next day, both armies partly lined up again. But neither side wanted to start fighting. King Charles sent a herald (a messenger) to Essex. The message offered a pardon if Essex would agree to the King's terms. But the messenger was treated roughly and sent back without delivering the message. Essex had received help from some of his soldiers who had been slow on the march. But he still pulled back that evening. Most of his army marched to Warwick Castle, leaving seven cannons on the battlefield.

Early on Tuesday, October 25, Prince Rupert led a strong group of horsemen and dragoons. He launched a surprise attack on what was left of Parliament's supplies at Kineton. He killed many wounded survivors of the battle found in the village.

Essex's choice to go north to Warwick allowed the King to continue south towards London. Rupert wanted to go quickly with only his cavalry. But with Essex's army still strong, the King chose to move more slowly with his whole army. After taking Banbury on October 27, he moved through Oxford, Aylesbury, and Reading. Meanwhile, Essex had gone straight to London. His army was made stronger by the London Trained Bands and many citizen volunteers. They were too strong for the King to try another battle when the Royalists reached Turnham Green. The King then went back to Oxford, which became his main base for the rest of the war. With both sides almost equally strong, the war would continue for years.

Many people agree that the Royalist cavalry's lack of discipline stopped the King from winning clearly at Edge Hill. This happened many times in the war. They would chase fleeing enemies and then break ranks to steal, instead of going back to attack the enemy foot soldiers. Byron's and Digby's men, especially, were not in the first fights. They should have been kept under control instead of being allowed to gallop off the battlefield. Patrick Ruthven was made Lord General of the King's Army, confirming his role as the acting commander in the battle.

On Parliament's side, Sir James Ramsay, who led the left-wing cavalry that ran away, was put on trial on November 5. The court said he had done everything a brave man should do.

The last person known to have survived the battle was William Hiseland. He also fought in the Battle of Malplaquet sixty-seven years later!

The Welch Medal

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Welch, who got the royal standard back, was made a knight by King Charles I the next morning. The King also ordered a special gold medal to be made for Welch. This was the first medal given to a person for bravery in battle. Captain John Smith also said he helped get the standard back. He was also made a knight. But the medal was made in Sir Robert Welch's name.

Later, when Prince Charles was in exile (living away from England), Welch made a mistake in how he defended Prince Rupert. Also, Prince Rupert was not popular with other Royalists in exile, and Welch was Irish. Because of this, Welch's role at Edge Hill was later downplayed. Instead, Smith (who was English) was wrongly seen as the main hero in later history books.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Edgehill para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Edgehill para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |