Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl of Essex

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Robert Devereux 3rd Earl of Essex

|

|

| Born | 11 January 1591 |

| Died | 14 September 1646 (aged 55) |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | Merton College, Oxford |

| Title | Earl of Essex |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Howard Elizabeth Paulet |

| Parent(s) | Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex Frances Walsingham |

Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex (born 11 January 1591 – died 14 September 1646) was an English Parliamentarian and soldier in the 1600s. When the Civil War began in 1642, he became the first main commander of the Parliamentarian army, also known as the Roundheads. However, he found it hard to win a big victory against King Charles I's Royalist army. Later, other leaders like Oliver Cromwell became more important. Essex resigned from his military role in 1646.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Robert Devereux was the son of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, who was a courtier and soldier during the time of Queen Elizabeth I. His mother was Frances Walsingham, whose father was Queen Elizabeth's spymaster. Robert was born in London.

He went to school at Eton College and then studied at Merton College, Oxford. He earned a Master of Arts degree in 1605.

Robert's father led a rebellion against Queen Elizabeth in 1601. He was later executed for treason, and the family lost their title. But when King James I became king, he decided to give the title back. So, in 1604, Robert Devereux became the 3rd Earl of Essex. He became good friends with Henry Stuart, who was the Prince of Wales.

Essex married Frances Howard when he was 13 and she was 14. After their marriage, he traveled around Europe from 1607 to 1609. When he returned, Frances asked for their marriage to be ended, and it was granted in 1613.

Later, on 11 March 1630, Essex married Elizabeth Pawlett. This marriage also faced difficulties, and they separated in 1631. They had a son named Robert, who was born in 1636 but sadly died a month later.

Military Experience Before the War

In 1620, Essex began his military career. Before the First English Civil War started, he served in Protestant armies in Germany and the Low Countries (which are now Belgium and the Netherlands). In 1620, he joined an expedition to defend a region called the Palatine. He also served with different leaders in 1621 and 1622. In 1624, he led a group of soldiers in a campaign to help the city of Breda, but it was not successful.

In 1625, he was a vice-admiral and led a group of soldiers in a failed English mission to Cadiz, Spain.

Even though these early military actions were not very famous, they helped Essex learn a lot about how wars were fought in Europe. He learned about different methods and strategies, especially in defending areas. People were very loyal to him, and he was always successful when he tried to get volunteers for these missions.

After a quiet period in the 1630s, Essex became a Knight of the Bath in 1638. He served in King Charles I's army during the first Scottish Bishops' War in 1639. He was a Lieutenant-General in the army in Northern England. However, he was not given a command in the second war in 1640. This made him side more with the King's opponents in Parliament.

Leading Up to the English Civil War

Robert Devereux was known for opposing the King's rule even in the 1620s. He was a leader of the "Country party" in the House of Lords. King James I once told him, "I fear thee not, Essex, if thou wert as well beloved as thy father, and hadst 40,000 men at thy heels," showing that the King was wary of Essex's popularity.

King Charles I, James's son, had ruled without Parliament for 11 years. In 1640, he had to call Parliament again to get money to fight rebellions in Scotland and Ireland. But many members of Parliament wanted to use this chance to challenge the King. Relations between Charles and Parliament quickly became very bad.

Essex was a strong Protestant and was known as one of the Puritan nobles in the House of Lords. He was friends with John Pym, who was one of the King's biggest critics in the House of Commons.

In 1641, Parliament passed a law against the King's minister, Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford. Strafford was very loyal to Charles, but Parliament wanted him executed. Essex strongly supported this action. To try and make peace with Parliament, King Charles agreed to the law and invited some of his critics to join his Privy Council.

Essex joined the Privy Council. He was made Captain General of the royal armed forces in the south in February and Lord Chamberlain in July. However, the relationship between Charles and Parliament continued to get worse.

On 4 January 1642, Charles went to the House of Commons to arrest Pym and four other members. They were accused of treason. But Essex had warned these five members about the King's plan, so they had already left. Charles was embarrassed. In the same month, Essex stopped attending the King's court. In April, he was removed from his job as Lord Chamberlain because he did not join the King in York. His role as Captain-General also ended.

As a fight between the King and Parliament seemed more likely, Parliament decided to create a Committee of Safety on 4 July 1642. This committee included members from both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Essex was one of the five peers on this committee. This group was meant to connect Parliament with the armies that supported them. At this time, these armies were mostly local defense groups and city militias who supported Parliament.

On 12 July, Parliament decided to create its own army. Essex was chosen to lead it because he was one of the few English nobles with military experience. The law that appointed Essex said he would be the "Captain-General and Chief Commander of the Army." It gave him all the power and authority that a general of an army would have. He accepted this important job. Parliament also gave him more power by making him Lord Lieutenant (a royal representative) in several counties.

Role in the English Civil War

Essex was in a difficult position in 1642. Parliament had voted to create an army to fight the King's forces, but they were not sure how to do it. This situation was new in English history. Parliament members wanted to make a deal with the King, but they did not want to commit treason.

The law that made Essex Captain-General said his job was to "preserve the Safety of his Majesty's Person." It did not tell him to fight the King directly, as that would have been treason. The law blamed the problems on people around the King, not Charles himself. It also said Essex had to follow instructions from Parliament, which limited his power as a commander. Despite these challenges, Essex managed to build an army that could fight the Royalist forces.

On 22 August 1642, King Charles raised his flag at Nottingham Castle. This was a symbolic declaration of war against Parliament. From this point, it was clear that the two armies would fight, starting the English Civil War. However, many Parliament supporters were still afraid of committing treason against the King. This held them back in the early years of the war. They also knew that an agreement with Charles would be needed to settle the kingdom after the war. A republic (a country without a king) was not their goal at this time. This gave Charles an advantage at first.

Royalist members of Parliament gradually left London in 1642. They later joined a rival Parliament in Oxford set up by the King. The remaining Long Parliament split into two groups. One group wanted to defeat the King in battle. The other, called the "peace party," wanted to force Charles to negotiate rather than defeat him. John Pym led a "middle group" that tried to keep good relations between the two.

Essex always supported Parliament. However, he sympathized with the peace party throughout the war. This made him less effective as a military leader.

Battle of Edgehill: First Major Fight

After some small fights, the first big battle between the two armies happened at the Battle of Edgehill on 23 October 1642. Both sides had large armies. Essex's personal guard included important figures like Henry Ireton and Thomas Harrison. However, both sides showed some lack of experience and discipline during the battle.

The battle started with Royalist cavalry charges led by Prince Rupert of the Rhine. These charges broke the Parliamentarian cavalry on both sides. The Royalist cavalry then chased the fleeing Parliamentarian horsemen, which was a mistake. Essex had kept two cavalry groups in reserve. As the main infantry (foot soldiers) fought, with Essex fighting alongside his troops, these two Parliamentarian cavalry groups attacked the Royalist foot soldiers, causing a lot of damage.

Both sides lost many soldiers, and the battle ended in a tie. Essex pulled his Parliamentarian army back to Warwick the next day.

This battle showed Essex's strengths and weaknesses as a military leader. His planning allowed the Parliamentarian forces to hold their ground. However, his cautious approach and unwillingness to chase the enemy meant his army was outmaneuvered. Charles was able to position his army between Essex's forces and London. This left the road to London open for Charles after the battle. Charles had also attacked Essex's army before it was fully ready.

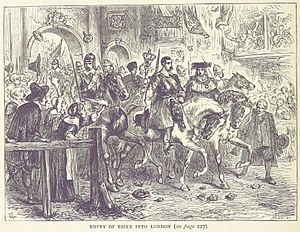

Luckily for Essex, Charles did not take full advantage of his position. The King decided to attack London with his full army, as he was also waiting for more soldiers. This allowed Essex and his army to rush back to London. Essex arrived in London on 7 November to a hero's welcome, before Charles could get there.

Battles Near London: Brentford and Turnham Green

On 12 November, Prince Rupert's Royalist army made its first major attack before marching on London. A small Parliamentarian group suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Brentford. The Royalists then looted the town. This made the people of London very angry and determined to resist a Royalist takeover.

On 13 November, Essex gathered 24,000 men for the Battle of Turnham Green. This included the soldiers from Edgehill, city militias, and volunteers from nearby counties. Essex and Major-General Phillip Skippon were key to this show of strength. They placed their soldiers in good defensive positions and kept morale high. Charles, with much fewer soldiers, did not attack. His army retreated after only a few shots were fired.

By the end of 1642, Essex's forces were still weaker than the Royalists. But Parliament had the support of the Scots, and thousands of other troops were ready to join their cause across the country. The stage was set for a long war.

First Battle of Newbury: A Strong Stand

After a long winter break, Essex's army captured Reading on 26 April 1643, after a 10-day siege. But progress towards the King's base at Oxford was slow after this. Some people began to question if Essex was truly willing to lead Parliament to victory.

His army's changing performance in 1643 was different from the success of the Eastern Association. This was a group of pro-Parliament militias from several eastern counties, led by Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester. One of their cavalry commanders was Oliver Cromwell. The Eastern Association became a very strong fighting force in 1643, largely thanks to Cromwell's regiment, known as the 'Ironsides'.

Still, 1643 was a good year overall for Essex's army. In what was perhaps his best moment, on 20 September, Essex's forces were stronger in the First Battle of Newbury. Even though they did not win a decisive victory, the Parliamentarians forced the Royalists to retreat to Oxford. This opened a clear road between Reading and London for the Parliamentarian army.

Lostwithiel Campaign: A Difficult Defeat

The year 1644 became a turning point in the First English Civil War. In February, Parliament formed an alliance with the Scots, creating the Committee of Both Kingdoms. Essex was appointed to this committee. This gave Parliament an advantage over the Royalists for the first time.

However, this year also saw a growing split within Parliament. Some wanted peace, while others wanted to defeat the King in battle. The death of John Pym in December 1643 meant Essex lost a key supporter in the House of Commons. A conflict between the two sides became unavoidable.

On 2 July 1644, Parliamentarian commanders defeated Royalist forces at the Battle of Marston Moor. Cromwell's actions with the Eastern Association were crucial to this victory.

At the same time, Essex tried to conquer the West Country. This was a strange move, and it went against the advice of the Committee of Both Kingdoms. There was some support for Parliament in Devon and Dorset, but almost no support in Royalist Cornwall.

Although the campaign started well, Essex's army was forced to surrender in September at Lostwithiel. They were outmaneuvered by the Royalists. Essex himself escaped in a fishing boat to avoid the humiliation of surrender. He left the task of surrendering to his second-in-command, Skippon.

End of His Military Career

The Lostwithiel campaign marked the end of Essex's military career. His army did participate in the Second Battle of Newbury on 27 October. However, Essex was sick in Reading at the time. His actions in the West Country had frustrated Cromwell, who was now the most important member of the House of Commons after his military victories.

Cromwell had started arguing with the Earl of Manchester, who was still his superior officer. Essex and Manchester still wanted peace, while Cromwell wanted to fight a more aggressive war against King Charles. After a month of arguments in Parliament, a big change was coming.

On 19 December 1644, the House of Commons approved the first Self-Denying Ordinance. This proposed that all members of Parliament should not be allowed to hold military commands. The House of Lords rejected this on 13 January 1645. However, on 21 January, the Commons passed the New Model Ordinance. This was a plan to create a single, united Parliamentarian army. It was approved by the Lords on 15 February. For over a month, the two Houses debated who would command this new army.

On 2 April, Essex and Manchester stepped down from their military roles. The next day, a new Self-Denying Ordinance was approved. This law removed members of both Houses from military commands, but it did not stop them from being reappointed later. Even though Essex still had many supporters, he had enough opponents to prevent him from becoming a military leader again at that time.

These changes led to the creation of the New Model Army. It was led by Sir Thomas Fairfax, the son of Lord Fairfax who had won the Battle of Marston Moor. Cromwell was quickly appointed as Lieutenant-General, becoming Fairfax's second-in-command.

Death and Funeral

For the rest of his life, Essex was connected with the Presbyterian group in Parliament. One of his last political efforts was a plan to build up Edward Massey's army to balance the power of the New Model Army. However, this plan failed when Parliament disbanded Massey's army in October 1646.

In 1645, Essex was given Somerhill House in Kent. This house had been taken by Parliament from his half-brother after the Battle of Naseby. On 1 December that year, Parliament voted for him to be made a Duke, but this never happened.

The Earl of Essex died in September 1646 without a child to inherit his title. After hunting in Windsor Forest, he had a stroke on September 10th and died in London four days later, at the age of 55. His earldom (title of Earl) ended with him. It was later brought back in 1661 for Arthur Capel. His death weakened the Presbyterian group in Parliament and also led to a decline in the influence of nobles who supported Parliament.

His death led to a large public display of sadness. Parliament contributed £5,000 for his funeral expenses, and he was buried in Westminster Abbey. For the funeral, the Abbey's chancel was draped in black. A statue of the Earl, dressed in military and Parliamentarian robes, was placed under a special structure designed by Inigo Jones. This statue remained there until a farmer, who was said to be a former Royalist soldier, chopped it down. The statue was put back, but King Charles II ordered it to be taken down during the Restoration. However, unlike most Puritans buried in the Abbey during the Civil War, Essex's body was allowed to remain buried there.

The Dowager Countess of Essex (his second wife) remarried around 1647 to Sir Thomas Higgons. She had two daughters with him before she died in 1656.

See also

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |