First Battle of Newbury facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First Battle of Newbury |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Charles I Prince Rupert Lord Grandison † Sir John Byron |

Earl of Essex Philip Skippon Philip Stapleton |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

14,500:

|

14,000:

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,300 | 1,200 | ||||||

The First Battle of Newbury was a major fight during the First English Civil War. It happened on September 20, 1643. The battle was between the Royalist army, led by King Charles I, and the Parliamentarian army, led by the Earl of Essex.

Before this battle, the Royalists had won many victories. They had taken important cities like Banbury, Oxford, Reading, and Bristol. This left the Parliamentarians in the west of England without a strong army. When King Charles started to besiege Gloucester, Parliament had to act. They quickly gathered an army under the Earl of Essex to stop the King.

After a long march, Essex surprised the Royalists and made them leave Gloucester. He then started to lead his army back to London. But King Charles quickly gathered his forces and chased Essex. The Royalists caught up to the Parliamentarian army near Newbury. This forced Essex to fight his way past them to continue his retreat.

Essex launched a surprise attack at dawn, taking control of high ground. This put King Charles's army in a difficult spot. The Royalists attacked many times, causing many injuries. Essex's forces slowly moved back and were almost surrounded. But Essex managed to rally his foot soldiers and counter-attacked. This attack slowed down when faced with Royalist cavalry. Essex asked for more troops, but they were attacked and forced to turn back. This created a gap in the Parliamentarian line. The Royalists hoped to break through and defeat Essex's army.

The Royalists pushed forward, but the London Trained Bands stopped them. As night fell, the battle ended. Both armies were very tired. The next morning, the Royalists had very little ammunition left. They had to let Essex's army pass and continue their journey to London.

Historians believe this battle was very important. It marked the highest point of the Royalist advance. It also led to the Solemn League and Covenant. This agreement brought the Scottish Covenanters into the war on Parliament's side. This helped Parliament eventually win the war.

Contents

What Led to the Battle?

When the English Civil War began, both sides thought it would end quickly. But by the end of 1642, it was clear this was not true. After the Battle of Edgehill in October, the Royalists marched towards London. They were stopped at the Battle of Turnham Green in November. King Charles then set up his main base in Oxford.

The Earl of Essex led the main Parliamentarian army. He was ordered to capture Oxford. On April 27, he captured Reading. He stayed there until mid-May, saying he needed more supplies and money to move forward.

Royalist Successes

Even though Essex was stuck outside Oxford, the Royalists were winning elsewhere. In the south-west, Royalist commander Sir Ralph Hopton secured Cornwall. He won the Battle of Braddock Down in January. Then, on July 13, he badly defeated William Waller's army at Battle of Roundway Down. This was a big victory for the Royalists. It left Parliament's forces in the west isolated.

Prince Rupert brought more troops from Oxford. On July 26, the Royalists captured Bristol. This was a huge win, as Bristol was the second-largest city in Britain.

Capturing Bristol

Capturing Bristol was a big success, but it also cost the Royalists a lot. They lost over 1,000 men and used up many supplies. Their armies needed to rest and regroup. Still, taking Bristol was seen as the high point for the Royalist side in the war.

After the city was captured, there was a disagreement about who should govern it. So, King Charles went to Bristol on August 1 to take charge of his forces. He called his war council to decide their next move. They needed to decide if the armies should join together and what their next target would be. The western army, though still strong, did not want to go further east. This was because Parliamentarian forces were still in Dorset and Cornwall. The army commanders feared their soldiers would refuse or leave if they tried to move.

Because of this, it was decided the western army would stay separate. They would remain in Dorset and Cornwall to clear out the remaining Parliamentarians. So, the western army, led by Lord Carnarvon, stayed there. They captured Dorchester without a fight on August 2. Prince Maurice left some soldiers to guard Bristol. He then went to Dorchester to take command.

The bigger questions were what to do with the Oxford army and their next plan. Rupert wanted to advance through the Severn Valley and capture Gloucester. This would allow Royalist forces from south Wales to join King Charles's army. Then they could attack London. But another group argued that London could be captured with the army as it was. They felt Gloucester would just be a distraction.

By August 6, Rupert's plan was dropped. Instead, they thought about a different way to take Gloucester. Early in the war, soldiers sometimes changed sides. Gloucester was led by Edward Massie. He was a mercenary who only worked for Parliament after the Royalists didn't give him a big command. Some Royalists thought there were secret supporters in Gloucester. Also, the governor of Sudeley Castle reported that Gloucester's soldiers would not fight a Royalist advance.

So, the war council decided to march on Gloucester. They didn't plan to attack it by force. They hoped the governor, Massie, would betray the city. William Legge, who had served with Massie before, contacted him. He asked Massie to surrender Gloucester to the King. Massie refused this message. But Legge's messenger said he met Massie again in secret. Massie supposedly said he was willing to surrender the town. Because of this, King Charles and the Oxford army marched to Gloucester on August 7.

The Siege of Gloucester

King Charles's main army started marching on August 7. They reached the village of Painswick a day later. Rupert's cavalry had already gone ahead and taken the village. Charles himself did not go with the main army. He rode across the Cotswolds to Rendcomb. There, he met more troops from Oxford on August 9.

On the morning of August 10, the Royalist army reached Gloucester. They surrounded the city with about 6,000 foot soldiers and 2,500 cavalry. King Charles sent messengers, protected by 1,000 musketeers. Around 2:00 pm, they read out the King's demands to 26 local council members and army officers, including Massie. The King promised to pardon the officers if they surrendered. He also said his army would not harm the city. He would leave only a small group of soldiers behind. If they did not surrender, he would take the city by force. The people would be responsible for any harm that happened.

Despite earlier hopes, Massie did not surrender. Soon after, the officers wrote a refusal and all signed it. No one knows for sure why Massie didn't surrender, even though he had hinted he would.

At this point, Charles held another war council. They decided it was still very important to take Gloucester. If Parliament kept it, it would block Royalist communication lines if they moved towards London. Also, Charles's reputation would suffer if he traveled so far and failed. He was "notoriously sensitive" about his image.

Charles's officers believed Gloucester's soldiers would run out of food and ammunition quickly. They thought the city could be taken in less than 10 days. They also believed Parliament didn't have a strong enough army to help the city. If Essex's forces didn't attack, the Royalists would take Gloucester. If they did attack, they would be tired and weaker than the Oxford army. This would allow Charles to destroy Parliament's last big army.

The Royalists, led by the Earl of Forth, began the siege. Rupert had suggested a direct attack, but this was rejected due to fears of many casualties. By August 11, the Royalist trenches were dug and artillery was ready. Massie tried to stop their work with musket fire, but it didn't work. With the siege ready, the Parliamentarians had no way out. Their only hope was to delay the Royalists until a relief army arrived.

Massie ordered raids under the cover of darkness. His second-in-command, James Harcus, led a raid on the artillery trenches. In return, the Royalists attacked the east of the city, but were driven back by cannons. On August 12, there were more raids, this time during the day. These cost the Royalists 10 men and a supply depot, with no Parliamentarian losses. Despite these raids, Royalist preparations continued. By evening, they began firing cannons at the town.

By August 24, the Royalists were running low on gunpowder and cannonballs. They still couldn't break through the city walls. Meanwhile, Essex was urgently preparing his army. Due to sickness and soldiers leaving, he had less than 6,000 foot soldiers and 3,500 cavalry. This force was not strong enough to defeat the Royalists. So, he asked for 5,000 more soldiers. Parliament in London responded by sending 6,000 men from the London Trained Bands. After adding other troops, the final force was about 9,000 foot soldiers and 5,000 cavalry.

The army gathered on Hounslow Heath and marched towards Aylesbury, arriving on August 28. This force was officially ready on August 30. After getting more troops from Lord Grey on September 1, they marched to Gloucester. On September 5, in heavy rain, the Parliamentarian army reached the town. They camped on Prestbury Hill, just outside Gloucester. Their arrival forced the Royalists to stop the siege. Both armies were wet and tired and not ready to fight.

The Chase to Newbury

King Charles's careful approach at Gloucester, focusing on fewer losses rather than a quick victory, cost the Royalists a lot. They had between 1,000 and 1,500 dead or wounded. But only about 50 people inside Gloucester were killed. Essex's army, on the other hand, was in good shape, but they lacked supplies.

If Essex stayed in the Severn Valley, he couldn't get more supplies. The London soldiers would want to go home. His army would be trapped. Charles, with bases in Oxford and Bristol, could starve them out. Other Royalist armies would then be free to move across Britain. So, Essex had no choice but to try to return to London. Going back across the Cotswolds, as he had come, would expose his army to Charles's cavalry on open ground.

One option was to march southeast to the River Kennet. He could cross it, go through Newbury, and return to Reading's forts. This would let him escape the Royalists and get back to London safely. The problem was the time it would take to cross the open land to the Kennet.

The second option, which Essex first chose, was to go north. He hoped to either fight in a better location or avoid the Royalists. If Essex could cross to the west bank of the River Avon, he could secure the bridges. This would stop the Royalists from crossing and attacking his army. His cavalry went to Upton on September 11 to protect the main army from Royalist interference. The rest of the soldiers quickly followed.

The Royalists were caught off guard. King Charles didn't find out about Essex's retreat for another 24 hours. During this time, the distance between the armies grew. The Royalists finally started marching on September 16. Rupert's cavalry rode ahead to try and disrupt the Parliamentarian retreat.

By September 18, Rupert's forces had caught up to the Parliamentarians near Aldbourne, Wiltshire. Essex had lost his advantage. Parliamentarian reports had made him believe Charles was going to Oxford and had given up. But Charles was only about 14 miles (22.5 km) away. These reports made Essex's army march slowly, only about 5 miles (8 km) a day. This allowed the Royalists to catch up quickly.

Realizing his mistake, Essex sped up his retreat. The Royalists followed closely. Both armies were heading for Newbury on similar paths. The Royalists' route through Faringdon and Wantage was longer, about 30 miles (48 km). The Parliamentarians only had to travel 20 miles (32 km). Charles sent Rupert with 7,000 cavalry to harass Essex's retreat. Rupert's forces met Essex's at Aldbourne Chase and fought. But Rupert didn't have enough troops for a full battle. Instead, he attacked part of Essex's army, causing confusion. This crucial delay allowed Charles's main forces to close the gap.

Rupert's actions, even after he pulled back, caused another delay for Essex. Essex spent much of September 19 caring for wounded soldiers. When he finally started moving again, he faced swamps and bogs. This slowed him down even more. Meanwhile, the Royalists marched across open chalk hills above the Kennet. These difficulties meant the Royalists reached Newbury before Essex. Both armies settled down for the night outside the town, too tired to fight immediately.

The Battle of Newbury

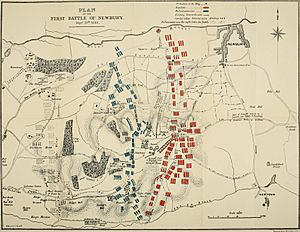

The Battlefield

The land around Newbury played a big role in how both sides fought. Most of the area was open country. But a crescent-shaped hill called Biggs Hill sat between the Royalist and Parliamentarian armies. On either side of Essex's army were open fields. The battlefield was bordered by the River Kennet on one side and the River Enborne on the other. Neither army tried to cross these rivers on foot.

Essex's clearest way to retreat was to push past the Royalists, secure the bridge, and return to London. But the open area leading to the bridge was very dangerous. Soldiers would be completely exposed and forced to march in narrow lines. This would make it hard for Essex to spread out his troops against a Royalist attack. His forces would be bunched up and easy targets for artillery. Even if Essex crossed the bridge, the other side had hundreds of meters of waterlogged ground. This would slow his soldiers and force them to leave behind their artillery, which would be a big embarrassment.

The only other option was to go around Newbury completely. But this would again mean moving through open fields. This would expose Essex's soldiers to attacks from the Royalist cavalry, who greatly outnumbered Parliament's cavalry. Fighting the Royalists directly meant moving into an area with "dense copses and innumerable banked hedges with ditches flanking fields and lining sunken lanes." This would allow troops to move hidden, but it would also make it hard to organize them. The many narrow lanes would limit movement during the battle.

Army Strengths

There are no exact lists of soldiers for Newbury. Official records from that time are scarce. But we can get some information from later reports and accounts. This helps us guess how each army was set up.

King Charles I personally led the Royalists. William Vavasour commanded the right side, Prince Rupert the left, and Sir John Byron the center. They had 20 cannons in total: 6 heavy, 6 medium, and 8 light. Early estimates said both armies had about 17,000 men. Modern estimates suggest the Royalists had about 7,500 foot soldiers and 7,000 cavalry.

Essex led the Parliamentarians. He commanded the whole army and also the right side. Philip Stapleton commanded the left side. They had two heavy cannons and about 20 light cannons. Most of their heavy artillery was left in Gloucester to defend the city. Estimates for the total number of men vary from 7,000 to 15,000. John Barratt, looking at losses at Gloucester, estimates Essex's force was about 14,000 men. This included 6,000 cavalry and dragoons, and 8,000 foot soldiers.

The Battle Begins

Essex Attacks First

The battle started on September 20. Essex's army woke up before dawn. Reports say he went "from regiment to regiment...[asking] them about a battle." After talking, the army advanced with "most cheerful and courageous spirits" around 7 am.

The army was split into three groups of foot soldiers, with cavalry on their sides. A reserve group was behind them. Stapleton's cavalry went first. They quickly cleared the Royalist guards. This allowed Essex's army to reach Wash Common. This was an open area between the two armies. The march took about an hour because the heavy clay soil was wet from the night's rain. The open space before Biggs Hill, their target, gave them a chance to regroup.

Rupert had placed cavalry guards on Biggs Hill. Their size is unknown, but they were large enough to attack Parliament's cavalry head-on. Stapleton waited until the Royalists were close before firing. This made their charge falter. Parliament's cavalry then advanced and drove them off with swords. The cavalry couldn't gain more ground. They had only fought a small part of the Royalist cavalry and didn't want to push against the larger group.

Led by Philip Skippon, Parliament's right side attacked their main target, nearby Round Hill. Their account says they "charged so fiercely that [they] beat [the Royalists] from the hill." But it doesn't mention any injuries or what happened to the Royalist cannons supposedly on the hill. The Royalists claimed the hill was undefended. The facts suggest this was closer to the truth. "The king and his generals had been caught napping." Capturing the hill allowed Skippon to place 1,000 musketeers on top. They could fire down on any Royalist advance.

Royalist Counter-Attack

Because of this quick advance, King Charles's army was in chaos. Skippon's force was organized and attacking their sides. The Royalist war council met again to discuss what happened. Accounts say the meeting was angry. The loss of Round Hill was called "a most gross and absurd error."

Rupert decided to try and stop both Essex and Skippon. He left two cavalry regiments with Byron. He led the rest of the cavalry to Essex's position on the left side. Byron was ordered to support an attack by Royalist musketeers on Skippon's force. He lined up his regiments behind the foot soldiers. They were "ready to second them in case the enemy's horse should advance towards them."

Rupert's advance has been criticized by both Parliamentarian and Royalist sources. Instead of a small fight, Parliament's strong resistance forced Rupert to send more and more troops. This turned a series of small fights into a full battle. The land made it hard for Rupert's forces to use their numbers advantage. But after three attacks, Stapleton's group broke. This allowed Rupert to go around Essex's left side. He stopped Essex's advance and captured five cannons. This came at a cost. The Royalists suffered many injuries. They failed to completely break Essex's foot soldiers. The foot soldiers stubbornly retreated, allowing Parliament's cavalry to regroup behind them. Even though his advance was stopped, Essex was not yet defeated.

Byron's attack on Skippon's musketeers in the center also went badly. He sent three regiments of foot soldiers forward. They suffered many injuries trying to take Round Hill. When the attack stalled, the cavalry had to be called in to push it forward. Despite heavy losses, this move succeeded. The only way forward was a narrow lane lined with Parliamentarian musketeers. Byron took Round Hill, pushing Parliament's foot soldiers back to a hedge. The attack eventually lost its force. Even though Round Hill was taken, Byron couldn't advance any further.

On the right side, William Vavasour tried to overwhelm Parliament's side. He used a large group of foot soldiers with some cavalry support. His first attack was pushed back by Parliament's cannons. But a second head-on attack forced Skippon's tired force in the center to send several regiments to help. The fight became a bloody hand-to-hand battle. Vavasour's force was eventually forced to retreat. The Parliamentarians did not give ground.

Stalemate and Nightfall

After heavy fighting, the Royalists had only pushed Essex's forces back a little. They had given some ground but had not retreated from the battle. Essex's main group of foot soldiers remained strong. To continue, Essex moved his foot soldiers and light cannons forward. Rupert's cavalry was too weak to defend against this advance because of its strong firepower. Instead, he ordered two regiments of foot soldiers, led by John Belasyse, to stop Essex.

Parliamentarian records say they were "hotly charged by the enemies' horse and foot." The Royalists slowly forced Essex back, but the fight lasted four hours. In response, Essex asked Skippon for more troops. Skippon sent Mainwaring's Regiment of foot soldiers from his line to replace some of Essex's tired soldiers. As soon as they arrived, two groups of cavalry and a regiment of foot soldiers under John Byron attacked them. They forced the regiment to retreat. The Royalists cut down the fleeing Parliamentarians. Byron said his force "had not left a man of them unkilled, but that the hedges were so high the horse could not pursue them."

The Royalists failed to push this attack because it was hard to move cavalry in the field. Essex briefly retook the ground. But the loss of this infantry regiment created a gap in Parliament's line. If Rupert could drive through this gap, he would split Essex's army into two parts and could surround them. Recognizing this, he began to move the Royalist forces. Two cavalry regiments and one infantry regiment under his command would keep Essex busy. Two regiments under Charles Gerard would push through the gap in Parliament's line.

Luckily for the Parliamentarians, Skippon saw this opening. He ordered the Red and Blue Regiments of the London Trained Bands to close the gap. They succeeded in connecting the two parts of Essex's army. But there was no cover. A Royalist battery of eight heavy guns on high ground began firing at them. They couldn't move because of their important position. They endured close-range fire "when men's bowels and brains flew in [their] faces." They resisted two attacks by Royalist cavalry and foot soldiers led by Jacob Astley.

Historian John Day notes that records show most Trained Band casualties were hit in the head. A survivor boasted that the artillery "did us no harm, only the shot broke our pikes." It seems the Royalist artillery was firing too high in the heat of battle. Despite this, the Royalist artillery fire had taken its toll. The Trained Band regiments were forced to retreat. The Royalists chased them. Only close-quarters musket fire allowed the militia to regroup without major losses. After regrouping, the militia was attacked again by two regiments of foot and two of cavalry. They surrounded the Londoners and dragged away a cannon, but they couldn't break them.

At this point, both armies began to separate. Some fighting continued as night fell. But by midnight, both forces had completely pulled back. Both army councils met. Essex's plan to force his way past the Royalists seemed possible. Many Parliamentarians expected the battle to continue, not wanting to give up the ground they had taken. The Royalists, however, had low morale, many losses, and a lack of supplies. They had used 80 of their 90 barrels of gunpowder. Rupert argued for the battle to continue, but he was out-voted. The next morning, Essex was allowed to bypass the Royalist force without issue and continue his retreat towards London.

Aftermath

The Parliamentarian army, now free from King Charles's forces, quickly retreated towards Aldermaston. They eventually reached Reading and then London. In London, Essex received a hero's welcome.

The Royalists, on the other hand, spent the next day recovering their injured soldiers. They found more than a thousand wounded men and sent them back to Oxford. After recovering their dead and wounded, the Royalists left 200 foot soldiers, 25 cavalry, and 4 guns in Donnington Castle to protect their rear. Then they marched to Oxford. They buried their dead senior officers in Newbury Guildhall.

The battle casualties at Newbury were about 1,300 losses for the Royalists and 1,200 for the Parliamentarians. The Royalist failure at Newbury was due to many reasons. Day credits Essex's better ability to save his forces throughout the campaign. This put the Royalists at a disadvantage in numbers at Newbury. He also notes the Royalists relied too much on cavalry. Essex "compensated for his much lamented paucity of cavalry by tactical ingenuity and firepower." He stopped Rupert's cavalry by using large groups of foot soldiers.

The Royalist foot soldiers also didn't perform as well. Essex's force stayed very organized, while the Royalists were described as less professional. Both Day and Blair Worden also say that the lack of ammunition and gunpowder was a very important reason for Charles's campaign failing.

Historians often focus on bigger battles like Edgehill and Marston Moor. But several historians who have studied this time believe the First Battle of Newbury was a turning point in the First English Civil War. It was the high point of the Royalist advance and a moment of great leadership for Essex. John Day writes that "Militarily and politically, Parliament's position at the beginning of October 1643 was demonstrably far stronger than in late July. With hindsight, the capture of Bristol was the high tide of King Charles' war, his best and only chance of ending the conflict on his own terms."

John Barratt noted that the Royalists had failed in "what might prove to have been their best chance to destroy the principle field army of their opponents, and hopes of a crushing victory which would bring down the Parliamentarian 'war party' lay in ruins." The strong Parliamentarian feelings after Newbury led to the signing of the Solemn League and Covenant. This brought a powerful Scottish army to fight the Royalists. "Thanks to the failure...to win a decisive victory there, the English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish subjects of all of King Charles' Three Kingdoms would henceforth play a bloody price in a steadily widening and deepening war."