Women in early modern Scotland facts for kids

Women in early modern Scotland, from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s, lived in a society where men generally held more power. However, women still played very important roles. They kept their own family names after marriage, showing they didn't just become part of their husband's family. In wealthy families, marriages were often planned for political reasons, and women like mothers or matchmakers were key in these talks.

Women were a big part of the working world. Many single women worked on farms, and married women helped with all major farm tasks, especially during harvest time. Widows sometimes ran schools, brewed drinks, or traded goods. But many poorer women struggled to survive.

Girls had fewer chances for formal education than boys. While some learned reading and household skills, writing was often not taught. Wealthy girls might have private teachers. From the 1600s, some women became known for their writing. Religion was also very important for women, giving them a way to express themselves. From the 1600s, women might have had more chances to join religious groups outside the main church.

At the start of this period, women had very few legal rights. For example, they couldn't act as witnesses in court.

Contents

Women's Place in Society

Early modern Scotland was a society where men were usually in charge. After the Protestant Reformation in the 1560s, the marriage ceremony even said that a wife was "under governance of her husband." Like in other parts of Western Europe, Scottish society taught daughters to obey their fathers and wives to obey their husbands.

However, because many people died young, women often took on important duties if their fathers or husbands passed away. Records from towns show that about one in five households were led by women, who often continued family businesses. Among noble families, becoming a widow could make a woman very rich and powerful. For example, Catherine Campbell became the wealthiest widow in Scotland in 1558. Margaret Ker, another widow, was described in 1635 as having the largest land ownership of any lady in Scotland.

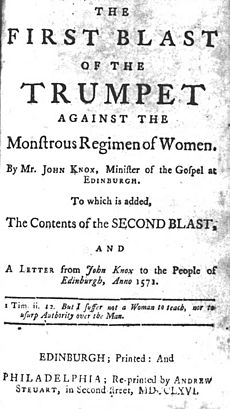

In politics, the idea of men always being in charge became tricky when women like Margaret Tudor and Mary of Guise ruled as regents (temporary rulers for young kings). It became even more complex when Mary, Queen of Scots became queen in 1561. Some men, like John Knox, were worried about women holding such power. Knox wrote a book in 1558 called The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women, saying that all queens should be removed from power. But most people in Scotland accepted Mary as their queen.

Foreign visitors sometimes noted that Scottish women were quite strong-willed. The Spanish ambassador to James IV of Scotland's court even said that Scottish women were "absolute mistresses of their houses and even their husbands."

Family Life and Marriage

In Scotland, family connections were mainly traced through the father's side. This was different from England, where connections were traced through both parents. Scottish women kept their own last names when they married. This showed that they didn't fully join their husband's family group. Marriages were meant to create friendships between different families, not just a new family bond.

Girls could marry from the age of 12, while boys could marry from 14. Many girls from wealthy families married in their teenage years. But most girls in the Scottish Lowlands (the southern and eastern parts of Scotland) married later, in their twenties. Before marrying, they often worked as servants to gain skills and resources for their own households. Women in the Scottish Highlands (the northern and western parts) might have married earlier because they had more children.

Marriages, especially among the upper classes, were often arranged for political reasons. There were complex talks about the tocher (dowry), which was money or property the bride's family gave to the groom's family. Some mothers were very involved in arranging marriages, like Lady Glenorchy in the 1560s and 1570s. They also acted as matchmakers, helping others find good partners.

Before the Reformation, the church had many rules about who could marry whom based on family ties. This often meant noble marriages needed special permission from the Pope. If a marriage became difficult, this permission could sometimes be used to cancel the marriage. Scotland was one of the first countries to allow divorce if one partner left the other. Unlike in England, people from lower social classes in Scotland could also start divorce cases.

Work and Daily Life

Women were a very important part of the workforce. Besides doing household chores, wives and female servants worked hard. Many single women worked away from their families as farm servants. Married women worked alongside their husbands on the farm, helping with all the main farming tasks. They were especially important during harvest, often making up most of the reaping team called the bandwin.

Women also played a big role in the growing textile (cloth-making) industries. They spun yarn and prepared the warp (the threads that run lengthwise) for men to weave. In the Highlands, women might have been even more important in farming. There's evidence that many men there thought farm work was beneath them, so women might have been the majority of the rural workers.

Some jobs were only done by women, such as midwives (who helped with childbirth) and wet-nurses (who breastfed other people's babies). Single women, especially widows, often ran their own businesses. They might keep schools, brew ale, or trade goods.

However, at the bottom of society, many widows with children lived very difficult lives. They were especially vulnerable when times were tough. Authorities were often concerned about "masterless women," who didn't have fathers or husbands to be responsible for them. These women might have made up as much as 18 percent of all households.

Education and Writing

By the late 1400s, Edinburgh had schools for girls, sometimes called "sewing schools." These were probably taught by women or nuns. Wealthy families also hired private teachers, and this education might have included girls. From the mid-1600s, boarding schools for girls appeared, especially in Edinburgh and London. These were often small, family-run schools led by women. At first, they were for girls from noble families. But by the 1700s, even daughters of traders and craftsmen started attending them. By the 1700s, many poorer girls learned in "dame schools." These were informal schools set up by widows or single women to teach reading, sewing, and cooking.

People widely believed that women had limited intelligence. But after the Reformation, there was a stronger desire for women to take personal responsibility for their morals, especially as wives and mothers. For Protestants, this meant being able to learn and understand the church's teachings and even read the Bible on their own. However, most people, even those who supported girls' education, thought girls shouldn't get the same academic education as boys.

Girls from lower social classes benefited from the growth of the parish school system after the Reformation. But they were usually fewer in number than boys, often taught separately, for less time, and to a lower level. They were frequently taught reading, sewing, and knitting, but not writing. Records show that about 90 percent of female servants couldn't write in the late 1600s and early 1700s. By 1750, about 85 percent of women of all social levels couldn't write, compared to 35 percent of men.

Among the nobility, there were many educated and cultured women, with Queen Mary being a famous example. By the early 1700s, their education was expected to include basic reading and math, playing musical instruments (like the lute or keyboard), needlework, cooking, and managing a household. Good manners and religious devotion were also important.

From the 1600s, some noble women became notable writers. The first book written by a woman and published in Scotland was Ane Godlie Dreame by Elizabeth Melville in 1603. Other important writers included Lady Elizabeth Wardlaw (1627–1727) and Lady Grizel Baillie (1645–1746). Between the late 1600s and early 1700s, 16 autobiographies written by women still exist, and all of them are mostly about religion.

Religion and Faith

Historians suggest that women had fewer ways to participate publicly than men. Because of this, being religious and having an active faith might have been even more important for wealthy women. Going to church was a big part of many women's lives. Women were mostly kept out of running the church. However, when heads of households voted for a new minister, some parishes allowed women who were heads of their households to vote.

The big changes of the 1600s saw women taking part in radical religious movements on their own. A famous example happened in 1637 when women threw their cuttie-stools (small stools) at the dean who was reading a new "English" prayer book in St. Giles Cathedral. This event helped start the Bishop's Wars (1639–40) between the Presbyterian Covenanters and the king. The king wanted a church structure similar to England's. Later, it was said that an Edinburgh woman named Jenny Geddes led these women.

According to historian R. A. Houston, women probably had more freedom to express themselves and control their spiritual lives in groups outside the main church, like the Quakers, who were present in Scotland from the mid-1600s. The idea of male authority could be challenged when women chose different religious leaders from their husbands and fathers. Among the Cameronians, who left the main church when the king brought back the English-style church structure in 1660, several reports say that women could preach and remove people from the church, but not baptize. Several women were even executed for their involvement in this movement.

See also

Images for kids

-

Agnes Douglas, Countess of Argyll (1574–1607)

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |