History of Christianity in Scotland facts for kids

The history of Christianity in Scotland tells the story of how Christianity came to Scotland and how it has changed over time, right up to today. Christianity likely arrived in southern Scotland when the Romans were in Britain. It was mainly spread by missionaries from Ireland starting in the 400s. Important figures like St Ninian, St Kentigern, and St Columba helped spread the faith.

The early Christian church in Ireland and Scotland was a bit different from the one led by Rome. For example, they calculated Easter differently and had a unique haircut for monks called tonsure. But by the mid-600s, the Celtic church in Scotland accepted Roman ways. Back then, monasteries were very important, and abbots (leaders of monasteries) were often more powerful than bishops.

During the Norman period, there were many changes. Churches became more organized, with local parishes and many new monasteries following European styles. The Scottish church also became independent from England. It developed its own system of dioceses (areas managed by bishops) and was called a "special daughter of the see of Rome." However, it didn't have its own Archbishops (senior bishops) until the late 1400s.

In the late Middle Ages, Scottish kings gained more power over who became church leaders. Even though traditional monastic life declined, new groups of friars (like Franciscans and Dominicans) became popular, especially in growing towns. New saints and ways of showing devotion also became common. Despite some problems with clergy numbers and quality after the Black Death in the 1300s, and some signs of heresy in the 1400s, the Church in Scotland remained strong.

In the 1500s, Scotland went through the Scottish Reformation. This led to a mostly Calvinist national church, called the Kirk, which was very Presbyterian (meaning it was run by elders, not bishops). In 1560, the Scottish Parliament adopted a new faith statement that rejected the Pope and the Catholic Mass. It was hard for the Kirk to reach the Highlands and Islands, but it slowly converted people. Compared to other countries, this change happened with less persecution.

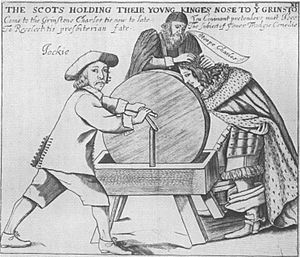

James VI (who was also James I of England) liked Calvinist beliefs but supported bishops. His son, Charles I, introduced changes that many saw as a return to Catholic practices. This led to the Bishop's Wars in 1639–40, which gave Scotland virtual independence and established a fully Presbyterian system led by the Covenanters. After the monarchy returned in 1660, Scotland got its Kirk back, but also the bishops. Many people, especially in the south-west, started attending illegal outdoor church meetings called conventicles. The government tried to stop these meetings in the 1680s, a time known as "the Killing Time" because of the harsh punishments. After the "Glorious Revolution" in 1688, Presbyterianism was restored.

The late 1700s saw the Church of Scotland start to split. This was due to disagreements over how the church should be run and who should appoint ministers. It also showed a bigger split between the Evangelicals (who focused on personal faith) and the Moderate Party (who were more open to new ideas). The First Secession in 1733 created new churches, and the second in 1761 led to the Relief Church. These churches grew stronger during the Evangelical Revival in the late 1700s. Christianity still didn't reach all parts of the Highlands and Islands easily. The Kirk's efforts were helped by missionaries from the SSPCK. Episcopalianism (which kept bishops) lost support because it was linked to the Jacobite rebellions.

From 1834, a period called the "Ten Years' Conflict" ended in a major split in the church, known as the Great Disruption of 1843. About a third of the clergy, mostly from the North and Highlands, left to form the Free Church of Scotland. These evangelical Free Churches grew quickly in the Highlands and Islands. In the late 1800s, debates between strict Calvinists and more liberal thinkers led to another split in the Free Church, with the strict Calvinists forming the Free Presbyterian Church in 1893.

After this, there were efforts to reunite the churches. Most of the Free Church rejoined the Church of Scotland in 1929. Small groups like the Free Presbyterians and a part of the Free Church that didn't merge in 1900 remained separate. Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and many Irish immigrants coming to Scotland led to Catholicism growing. The Catholic Church re-established its hierarchy (system of bishops) in Scotland in 1878. Episcopalianism also grew in the 1800s, forming the Episcopal Church in Scotland in 1804, which was linked to the Church of England. Other groups like Baptists, Congregationalists, and Methodists also grew.

In the 1900s, new Christian groups like the Brethren and Pentecostal churches appeared. However, after World War II, fewer people went to church, and many churches closed. In the 2001 census, about 42% of people in Scotland identified with the Church of Scotland, 16% with Catholicism, and nearly 7% with other Christian groups. This means about 65% of the population were Christian. Other groups in Scotland include the Jehovah's Witnesses and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. About 27.5% of people said they had no religion.

The Church of Scotland is recognized as the national church. It is not controlled by the government. The monarch (currently Queen Elizabeth II) is an ordinary member of the Church of Scotland and is represented at its main meeting, the General Assembly. In the 1900s, many Catholics came to Scotland from countries like Italy, Lithuania, and Poland. However, the Catholic Church has also seen fewer people attending services. Some parts of Scotland, especially around Glasgow, have had problems with sectarianism (prejudice between different religious groups). This is sometimes seen in football rivalry between traditionally Catholic and Protestant teams like Celtic and Rangers.

Middle Ages

Early Christianity in Scotland

Christianity probably arrived in what is now southern Scotland during the time of the Roman Empire in Britain. While the Picts and Scots living outside Roman control likely remained pagan, most experts believe Christianity survived after the Romans left. It continued among the Brythonic people in places like Strathclyde. However, it probably faded as pagan Anglo-Saxons moved into what is now the Scottish Lowlands.

In the 500s, missionaries from Ireland began working in Britain. This movement is linked to St Ninian, St Kentigern, and St Columba. St Ninian is now thought to be a figure created by the Northumbrian church. Little is known about St Kentigern (who died in 614), but he likely worked in the Strathclyde area. St Columba probably learned from Uinniau (another name for Ninian). He left Ireland and founded a monastery on Iona island in 563. From there, he went on missions to the Scots of Dál Riata (who came from Ireland) and the Picts (descendants of the Caledonians). However, it seems both the Scots and Picts had already started becoming Christian before Columba arrived.

The Celtic Church

The early religion of the Picts was likely similar to other Celtic pagan beliefs. We don't know exactly when Pictish kings became Christian, but there are stories linking Saint Palladius to Pictland. Saint Patrick even mentioned "apostate Picts." It seems the Pictish leaders slowly converted over a long time, starting in the 400s and finishing by the 600s. Recent discoveries at Portmahomack show a monastery was founded there in the late 500s, around the time of King Bridei and Columba.

The spread of Christianity throughout Pictland took much longer. Pictland was influenced not only by Iona and Ireland but also by churches in England. For example, King Nechtan mac Der Ilei supported Roman customs, like how Easter was dated and the style of tonsure. In 717, Nechtan reportedly expelled monks from Iona. This might have been because of the Easter debate, or it could have been to increase the king's power over the church. Still, place names show that Iona had a wide influence in Pictland.

Gaelic Monasteries

Scottish monasteries looked very different from those in Europe. They were often isolated groups of wooden huts surrounded by a wall. You can still see Irish architectural influence in the round towers at Brechin and Abernethy. Some early Scottish monasteries had families of abbots (leaders), who were often married clergy. This was common north of the Forth River, in places like Dunkeld and Brechin.

Perhaps because of this, a group of reforming monks called Céli Dé (meaning "vassals of God"), also known as culdees, started in Ireland and came to Scotland in the late 700s and early 800s. Some Céli Dé took vows to live simply and without marriage. Some lived alone as hermits, while others lived near or within existing monasteries. Even when new types of monasteries arrived from the 1000s, the Céli Dé continued alongside them until the 1200s.

Scottish monks played a big part in the Hiberno-Scottish mission. This is when Scottish and Irish clergy went on missions to the growing Frankish Empire in Europe. They founded monasteries, often called Schottenklöster (meaning 'Gaelic monasteries' in German), many of which became Benedictine (a type of monastic order) in what is now Germany. Scottish monks, like St Cathróe of Metz, became local saints in these areas.

New Monasteries from Europe

New types of monasteries from Europe came to Scotland thanks to Saxon princess Queen Margaret (around 1045–93). She was the second wife of King Máel Coluim III (ruled 1058–93). Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury, sent monks for a new Benedictine abbey at Dunfermline around 1070.

Later kings like Edgar (ruled 1097–1107), Alexander (ruled 1107–24), and David I (ruled 1124–53) supported religious orders that started in France in the 1000s and 1100s. These included the Augustinians, who founded their first priory (a type of monastery) in Scotland at Scone in 1115. By the early 1200s, Augustinians had joined, taken over, or reformed Céli Dé places and built many new ones, like Holyrood Abbey.

The Cistercians built foundations at Melrose (1136) and Dundrennan (1142). The Tironensians built at Selkirk, then Kelso, Arbroath, Lindores, and Kilwinning. The Cluniacs founded an abbey at Paisley. The Premonstratensians had foundations at Whithorn, and the Valliscaulians (from Burgundy) at Pluscarden. Military orders like the Knights Templars and Knights Hospitallers also came to Scotland under David I.

The Scottish Church's Independence

Before the Norman period, Scotland didn't have a clear system of dioceses (areas managed by bishops). There were bishops in old churches, but some are barely mentioned in records, and there were often long periods without a bishop. Around 1070, during Malcolm III's reign, there was a "Bishop of Alba" in St. Andrews, but his power over other bishops isn't clear.

After the Normans conquered England, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York both claimed power over the Scottish church. When David I appointed John, a monk, as Bishop of Glasgow around 1113, the Archbishop of York demanded John's obedience. A long argument followed. John went to Rome to appeal but wasn't successful. He still refused to obey York, even with pressure from the Pope.

David I tried to get the Bishop of St. Andrews made an independent archbishop. At one point, David and his bishops even threatened to support an anti-pope. When Bishop John died in 1147, David appointed another monk, Herbert, and Glasgow continued to refuse to obey York.

The church in Scotland finally became independent after a Papal Bull (a special order from the Pope) from Pope Celestine III in 1192. This meant all Scottish bishoprics, except Galloway, were formally independent of York and Canterbury. However, unlike Ireland, which got four Archbishops, Scotland didn't get any. The entire Ecclesia Scoticana (Scottish Church) became a "special daughter of the see of Rome." It was run by councils of Scottish bishops, with the Bishop of St Andrews becoming the most important. It wasn't until 1472 and 1492 that St Andrews and Glasgow became archbishoprics.

Church Leaders in the Late Middle Ages

Until the early 1300s, the Pope tried to limit clergy from holding multiple church jobs at once. But with low pay and a shortage of clergy, especially after the Black Death in the 1300s, the number of clerics holding two or more jobs increased quickly in the 1400s. This meant that local parish priests often came from less educated backgrounds. People often complained about their education, but there's no clear proof that standards were actually getting worse.

Like in other parts of Europe, the Pope's power weakened during the Papal Schism. This allowed the Scottish king to gain control over important church appointments in Scotland, which the Pope recognized in 1487. This led to the king putting his friends and family in key church positions. For example, King James IV's son, Alexander, was made Archbishop of St. Andrews at age eleven. This increased the king's influence and led to accusations of corruption and favoritism. Despite this, the relationship between the Scottish king and the Pope was generally good.

Saints in Scotland

Like all Christian countries, one important part of Medieval Scotland was the worship of saints. Saints from Ireland who were especially honored included various figures named St Faelan and St. Colman, as well as saints Findbar and Finan. Columba remained a very important figure into the 1300s. King William I (ruled 1165–1214) even gave money to a new church at Arbroath Abbey in his honor.

In Strathclyde, the most important saint was St Kentigern, whose worship (under the nickname St. Mungo) became centered in Glasgow. In Lothian, it was St Cuthbert, whose bones were moved around Northumbria after Vikings attacked Lindisfarne, before ending up in Durham Cathedral. After his death around 1115, a saint's following grew in Orkney, Shetland, and northern Scotland around Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney.

The worship of St Andrew was established on the east coast at Kilrymont by the Pictish kings as early as the 700s. The shrine, which from the 1100s was said to hold the saint's bones brought to Scotland by Saint Regulus, became known simply as St. Andrews by the 1100s. It became more and more linked with Scottish national identity and the royal family. Queen Margaret was made a saint in 1250. After her remains were moved to Dunfermline Abbey, she became one of the most respected national saints. In the late Middle Ages, "international" saints became more important in Scotland, especially those connected to the Virgin Mary and Christ, but also St Joseph, St. Anne, the Three Kings, and the Apostles.

Everyday Religion

Older histories often said the late medieval Scottish church was corrupt and unpopular. However, newer research shows how it actually met the spiritual needs of different groups of people. Historians have noticed that monasticism declined during this time. Many religious houses had fewer monks, and those who remained often lived more individual lives. New gifts of money to monasteries from nobles also decreased in the 1400s.

In contrast, towns saw a rise in mendicant orders of friars in the late 1400s. These friars focused on preaching and helping the local people. The Observant Friars formed a Scottish group from 1467, and the older Franciscans and Dominicans were recognized as separate groups in the 1480s. In most towns, unlike in England where churches were everywhere, there was usually only one main parish church. But as the idea of Purgatory became more important, the number of small chapels, priests, and Masses for the dead within these churches grew quickly.

The number of altars dedicated to saints also increased dramatically. St. Mary's in Dundee might have had 48, and St Giles' in Edinburgh had over 50. The number of saints celebrated in Scotland also grew, with about 90 new ones added to the prayer book used in St Nicholas church in Aberdeen. New ways of showing devotion to Jesus and the Virgin Mary also reached Scotland in the 1400s. These included devotion to The Five Wounds, The Holy Blood, and The Holy Name of Jesus. New feast days like The Presentation, The Visitation, and Mary of the Snows were also introduced.

There were also efforts to make Scottish church services different from those in England. A printing press was set up in 1507 to print Scottish prayer books instead of the English Sarum Use. Heresy, in the form of Lollardry, began to arrive in Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early 1400s. Although some people were burned for it and there seemed to be some support for its ideas against church rituals, it probably remained a small movement.

Early Modern Period

The Reformation in Scotland

Early Protestant Ideas

In the 1500s, Scotland experienced a Protestant Reformation. This led to a mostly Calvinist national church, called the Kirk, which was strongly Presbyterian. This greatly reduced the power of bishops, though it didn't get rid of them entirely. Early in the century, the teachings of Martin Luther and then John Calvin began to influence Scotland. This happened especially through Scottish scholars who had studied in Europe and England, many of whom had been Catholic priests. English influence was also direct, with books, Bibles, and Protestant writings being sent to the Lowlands during an invasion in 1547.

The work of the Scottish Lutheran, Patrick Hamilton, was very important. He and other Protestant preachers were executed in 1528. Zwingli-influenced George Wishart was burned at the stake in St. Andrews in 1546 by order of Cardinal Beaton. These executions did not stop the spread of Protestant ideas. Wishart's supporters, including some Fife landowners, killed Beaton soon after and took over St. Andrews Castle. They held it for a year before being defeated with help from French forces. The survivors, including the chaplain John Knox, were forced to be galley slaves. This helped create anger against the French and made martyrs for the Protestant cause.

The Reformation Settlement

Some tolerance and the influence of Scots living abroad, along with Protestants in other countries, helped Protestantism grow. A group of landowners declared themselves the Lords of the Congregation in 1557 and started to represent Protestant interests in politics. The French alliance collapsed, and English help in 1560 meant that a small but powerful group of Protestants could bring reform to the Scottish church.

In 1560, while the young Mary, Queen of Scots, was still in France, the Scottish Parliament adopted a new statement of faith. This statement rejected the Pope's authority and the Catholic Mass. John Knox, who had escaped from the galleys and spent time in Geneva (where he became a follower of Calvin), became the most important leader. The Calvinist beliefs of Knox and the other reformers led to a system that adopted Presbyterian church government. This meant getting rid of most of the fancy traditions of the Medieval church. By the 1590s, Scotland was organized into about fifty presbyteries, each with about twenty ministers. Above them were a dozen or so synods, and at the top was the General Assembly.

This gave a lot of power within the new Kirk to local landowners, who often controlled who became clergy. This led to widespread, but generally orderly, destruction of religious images (iconoclasm). At this time, most people were probably still Catholic. The Kirk found it hard to reach the Highlands and Islands, but it slowly converted people. Compared to other reformations, this process happened with relatively little persecution.

King James VI

The reign of the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots eventually ended in civil war. She was removed from power, imprisoned, and later executed in England. Her baby son, James VI, became King of Scots in 1567. He was raised as a Protestant while the country was run by various regents. After he took personal control in 1583, he favored Calvinist beliefs but also supported bishops.

When he inherited the English crown, he ruled Scotland from London through the Privy Council. He also gained more control over the meetings of the Scottish General Assembly and increased the number and powers of Scottish bishops. In 1618, he held a General Assembly and pushed through "Five Articles." These included practices that had been kept in England but mostly abolished in Scotland, the most controversial being kneeling to receive communion. Although these articles were approved, they caused widespread opposition and anger. Many people saw them as a step back towards Catholic practices.

The 1600s

The Covenanters

James VI was followed by his son Charles I in 1625. While his father had divided his opponents, Charles united them. Charles relied heavily on the bishops, especially John Spottiswood, Archbishop of St. Andrews, whom he eventually made chancellor. Early in his reign, Charles took back church lands that had been sold since 1542. This helped the Kirk's finances but threatened the wealth of nobles who had gained from the Reformation.

In 1635, without asking the General Assembly or Parliament, the king approved a book of church laws that made him head of the Church. It also ordered unpopular rituals and forced the use of a new prayer book. When this new prayer book appeared in 1637, it looked like an English-style book. This caused anger and widespread riots. One famous story says a woman named Jenny Geddes threw a stool during a service in St Giles Cathedral to start the riot.

The Protestant nobles led the popular opposition. Representatives from different parts of Scottish society signed the National Covenant on February 28, 1638. This document objected to the King's new church rules. The king's supporters couldn't stop the rebellion, and the king refused to compromise. In December 1638, at a General Assembly meeting in Glasgow, the Scottish bishops were officially removed from the Church. The Church was then fully established on a Presbyterian basis.

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Scots and the king both raised armies. After two Bishop's Wars in 1639 and 1640, the Scots won. Charles gave in, leaving the Covenanters in independent control of Scotland. He was forced to call the English Parliament, which led to the English Civil War starting in 1642. The Covenanters sided with Parliament. In 1643, they signed the Solemn League and Covenant, which guaranteed the Scottish Church's Presbyterian system and promised more reforms in England.

By 1646, a Royalist campaign in the Highlands and the Royalists in England had been defeated, and the king had surrendered. Relations with the English Parliament and the increasingly powerful English New Model Army became tense. Control of Scotland went to those willing to compromise with the king. This "Engagement" with the King led to a Second Civil War. A Scottish invading army was defeated at the Battle of Preston by Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army. After a coup called the Whiggamore Raid, the Kirk Party regained control in Scotland.

Scotland under the Commonwealth

After the king was executed in January 1649, England was declared a commonwealth. The Scots then declared his son, Charles II, as their king. The English responded by invading Scotland. After the Scots were defeated at Dunbar in 1650 and Worcester in 1651, the English occupied Scotland in 1652. Scotland was then declared part of the Commonwealth.

The Kirk became deeply divided, partly as people looked for reasons for their defeat. Different groups created rival "resolutions" and "protests," which gave their names to the two main parties: the Resolutioners, who were willing to work with the royalists, and the stricter Protesters, who wanted to remove any royalist connections from the Kirk. The split between these groups became almost impossible to fix. The English government accepted Presbyterianism as a valid church system, but didn't agree it was the only one. The Kirk continued to function much as before. Tolerance didn't extend to Episcopalians (who supported bishops) and Catholics, but if they didn't draw attention to themselves, they were mostly left alone.

The Monarchy Returns

After the monarchy returned in 1660, Scotland got its Kirk back, but also the bishops. Laws passed since 1633 were cancelled, undoing the Covenanters' gains from the Bishops' Wars. However, the church courts (kirk sessions, presbyteries, and synods) were brought back. The return of bishops caused particular trouble in the south-west of Scotland, an area with strong Presbyterian beliefs. Many people there left the official church and started attending illegal outdoor meetings led by ministers who had been removed from their churches. These were called conventicles.

Official attempts to stop these meetings led to a rebellion in 1679. This rebellion was defeated by James, Duke of Monmouth, the King's illegitimate son, at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge. In the early 1680s, a more intense period of persecution began. This time was later known in Protestant histories as "the Killing Time." During this period, dissenters were quickly executed by soldiers or sentenced to transportation or death by Sir George Mackenzie, the Lord Advocate.

The Glorious Revolution

Charles died in 1685, and his brother became James VII of Scotland (and II of England). James put Catholics in key government positions, and even attending a conventicle was made punishable by death. He ignored Parliament, removed people from his Council, and forced through religious toleration for Roman Catholics, which angered his Protestant subjects. People believed the king would be followed by his Protestant daughter Mary, who was married to William of Orange, the ruler of the Netherlands. But in 1688, James had a male heir, James Francis Edward Stuart, which made it clear his policies would continue.

Seven leading Englishmen invited William to England, and he landed with 40,000 men. James fled, leading to the almost bloodless "Glorious Revolution". The final agreement restored Presbyterianism in Scotland and abolished the bishops, who had generally supported James. However, William, who was more tolerant than the Kirk tended to be, passed laws that allowed the Episcopalian clergy (who had been removed after the Revolution) to return.

Modern Period

The 1700s

The late 1700s saw the Church of Scotland begin to split. These divisions were caused by disagreements over church government and who should appoint ministers. But they also showed a wider split between the Evangelicals (who feared religious extremism) and the Moderate Party (who accepted new ideas from the Enlightenment). The legal right of wealthy patrons to choose ministers for local churches led to small splits from the church. The first, in 1733, known as the First Secession, led to the creation of several new churches. The second, in 1761, led to the founding of the independent Relief Church. These churches grew stronger during the Evangelical Revival in the late 1700s.

Long after the Church of Scotland became strong in the Lowlands, Highlanders and Islanders held onto an older form of Christianity mixed with folk beliefs. The remote location and lack of Gaelic-speaking clergy made it hard for the established church to spread its message. The late 1700s saw some success, thanks to the efforts of SSPCK missionaries and changes in traditional society. Catholicism had been pushed to the edges of the country, especially the Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands. Conditions also worsened for Catholics after the Jacobite rebellions, and Catholicism became little more than a poorly run mission. Episcopalianism, which had kept supporters through the civil wars and changes in government in the 1600s, was also important. Since most Episcopalians had supported the Jacobite rebellions in the early 1700s, they also faced difficulties.

The 1800s

After many years of struggle, in 1834, the Evangelicals gained control of the General Assembly. They passed the Veto Act, which allowed church members to reject ministers chosen by patrons. The "Ten Years' Conflict" that followed involved legal and political arguments. It ended in defeat for those who opposed "intrusion" (ministers being forced on congregations) in the civil courts. This led to a major split from the church by some of the non-intrusionists, led by Dr Thomas Chalmers. This event is known as the Great Disruption of 1843.

About a third of the clergy, mostly from the North and Highlands, left to form the separate Free Church of Scotland. These evangelical Free Churches, which were more accepting of the Gaelic language and culture, grew quickly in the Highlands and Islands. They appealed much more strongly than the established church. Chalmers's ideas shaped the breakaway group. He emphasized a social vision that brought back and preserved Scotland's community traditions during a time of social stress. Chalmers imagined small, equal, church-based communities that were self-contained. These communities recognized the individuality of their members and the need for cooperation. This vision also influenced the mainstream Presbyterian churches, and by the 1870s, the established Church of Scotland had adopted it. Chalmers's ideals showed that the church cared about the problems of city life, and they were a real attempt to overcome the social fragmentation that happened in industrial towns and cities.

In the late 1800s, the main debates were between strict Calvinists and more liberal thinkers who didn't take the Bible literally. This led to another split in the Free Church, as the strict Calvinists left to form the Free Presbyterian Church in 1893. However, there were also moves towards reunion. Some secessionist churches joined to form the United Secession Church in 1820. This group then united with the Relief Church in 1847 to form the United Presbyterian Church. This in turn joined with the Free Church in 1900 to form the United Free Church of Scotland. The removal of laws about lay patronage (patrons choosing ministers) allowed most of the Free Church to rejoin the Church of Scotland in 1929. The splits left small denominations, including the Free Presbyterians and a part of the Free Church that had not merged in 1900.

Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and many Irish immigrants coming to Scotland, especially after the famines of the late 1840s, led to a big change for Catholicism. These immigrants mainly came to growing lowland cities like Glasgow. In 1878, despite opposition, the Roman Catholic church system was restored in Scotland, and Catholicism became a significant religion. Episcopalianism also grew in the 1800s as the issue of royal succession became less important. It was established as the Episcopal Church in Scotland in 1804, as an independent organization linked to the Church of England. Baptist, Congregationalist, and Methodist churches had appeared in Scotland in the 1700s, but they didn't start growing significantly until the 1800s. This was partly because more radical and evangelical traditions already existed within the Church of Scotland and the free churches. From 1879, they were joined by the evangelical revivalism of the Salvation Army, which tried to make big progress in the growing cities.

Christianity Today

In the 1900s, other Christian groups joined the existing ones, including the Brethren and Pentecostal churches. Although some groups grew, after World War II, there was a steady overall decline in church attendance. This led to church closures for most denominations. In the 2001 census, 42.4% of people identified with the Church of Scotland, 15.9% with Catholicism, and 6.8% with other forms of Christianity. This made up about 65% of the population. Other groups in Scotland include the Jehovah's Witnesses, Methodists, the Congregationalists, and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. About 5.5% did not state a religion. 27.5% said they had no religion. More recent studies suggest that the number of people who don't identify with a religion might be much higher, between 42% and 56%.

The Church of Scotland is recognized as the national church (under the Church of Scotland Act 1921). It is not controlled by the state. The monarch (currently Queen Elizabeth II) is an ordinary member of the Church of Scotland. She is represented at the General Assembly by her Lord High Commissioner. For much of the 1900s, many Catholics moved to Scotland from Italy, Lithuania, and Poland. However, the church has been affected by the general decline in church attendance. Between 1994 and 2002, Roman Catholic attendance in Scotland dropped by 19%, to just over 200,000. By 2008, the Bishops' Conference of Scotland estimated that 184,283 people attended mass regularly, which was 3.6% of Scotland's population at that time.

Some parts of Scotland (especially the West Central Belt around Glasgow) have experienced problems caused by sectarianism (prejudice between different religious groups). While football rivalry between Protestant and Catholic clubs exists in most of Scotland, the traditionally Roman Catholic team, Celtic, and the traditionally Protestant team, Rangers, have kept their sectarian identities. Celtic has employed Protestant players and managers, but Rangers has a tradition of not recruiting Catholics.

Images for kids

-

The Monymusk Reliquary, or Brecbennoch, dates from c. 750, and purportedly enclosed bones of Columba

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |