History of popular religion in Scotland facts for kids

The history of popular religion in Scotland explores how ordinary people in Scotland have practiced their faith. This includes beliefs and customs outside of official church rules. From ancient times to today, religion has shaped Scottish life.

Before Christianity arrived, people in Scotland likely followed beliefs similar to Celtic polytheism. They worshipped spirits and sacred wells. Christian missionaries from Ireland, Rome, and England brought Christianity starting in the 500s. But some older pagan customs continued.

In the Middle Ages, the church played a big role. Priests performed baptisms, masses, and burials. They also gave sermons and prayed for the dead. The church guided people on right and wrong. It also influenced daily life with rules about fasting and purity. A key part of medieval Scottish faith was the Cult of Saints. People visited shrines dedicated to saints like St Andrew. Many Scots also joined the Crusades.

Later, in the 1400s, new groups of friars became popular in towns. They focused on preaching to people. Beliefs about Purgatory grew, leading to more chapels and prayers for the dead. New devotions to Jesus and the Virgin Mary also spread. Ideas like Lollardry, which questioned church teachings, also reached Scotland but didn't become widespread.

The Scottish Reformation in the mid-1500s changed religion greatly. Sermons became the main part of worship. Laws against witchcraft were introduced, leading to many trials. In the 1600s, Scottish Protestantism focused heavily on the Bible. Church leaders, called kirk sessions, had strong power over people's behavior. They also helped the poor and managed schools.

Later, in the 1800s, industrial growth and city living changed religious life. Sunday schools and other groups tried to help people connect with faith. The temperance movement encouraged people to avoid alcohol. After World War I, church attendance declined, though it rose briefly in the 1950s. In the 1900s, tensions between Protestants and Catholics, especially in football, became a problem. However, churches also started working together more. Today, Scotland is home to many different religions, including Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism, largely due to immigration.

Contents

Ancient Scottish Beliefs

We know very little about religion in Scotland before Christianity. The Picts, who lived in Scotland, did not leave many written records. So, we learn about their beliefs from other Celtic cultures. We also use archaeological finds and writings from later Christian authors.

It is thought that ancient Scottish religion was like Celtic polytheism. This means people worshipped many gods and spirits. Over 200 Celtic gods have been named. Some, like Lugh and The Dagda, come from Irish stories. Others, like Teutatis and Cernunnos, are known from places like Gaul (modern France).

Celtic pagans built temples and shrines. They made offerings and performed sacrifices to their gods. Some accounts even mention human sacrifice. There were also special religious leaders called druids. We don't know much about them, but Irish legends link druids with the Picts.

Christian writers also mentioned Picts worshipping "demons." One story tells of St. Columba removing a demon from a well in Pictland. This suggests that worshipping well spirits was common. Roman writings also mention the goddess Minerva being worshipped at wells. A Pictish stone near Dunvegan Castle on Skye also supports this idea.

Early Christian Times

Christianity came to Scotland from the 500s. Missionaries from Ireland and Scotland, and some from Rome and England, spread the faith. Important figures include St Ninian, St Kentigern, and St Columba. Even after Christianity arrived, some older pagan customs continued. For example, sacred wells became places of pilgrimage.

Most of what we know about early Christian practices comes from monks. Their lives involved daily prayers and the Mass. Bishops and priests also played a vital role. Bishops worked with local leaders and ordained new clergy. They also cared for the poor, hungry, and sick.

Priests performed baptisms, masses, and burials. They prayed for the dead and gave sermons. They also anointed the sick and gave communion to the dying. The church encouraged giving to charity and being welcoming to others. It also set rules for marriage and inheritance. The church influenced daily life with rules about fasting, diet, and ritual cleansing.

Early churches were often made of wood. So, little physical evidence remains. But place names often include words for church, like cill or eccles. Stone crosses and Christian burials also show where churches once stood. Over time, wooden churches were replaced by stone buildings. Many were built by local lords for their people.

In the 700s, Viking raids began on monasteries like Iona. Orkney, Shetland, and the Western Isles were taken over by Norsemen. There is some evidence of Norse burial customs, but less proof of their gods being worshipped. It is likely that pagan practices existed in early Scandinavian Scotland.

Medieval Faith and Saints

A big part of religion in Medieval Scotland was the Cult of Saints. People greatly respected saints from Ireland, like St Faelan and St. Colman. Columba remained a very important saint. King William the Lion (who ruled from 1165–1214) even built a new church at Arbroath Abbey for his relics.

Local saints were also important for people's identity. In Strathclyde, St Kentigern (also known as St. Mungo) was key, especially in Glasgow. In Lothian, St Cuthbert was revered. After Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney was killed around 1115, people in Orkney and northern Scotland began to worship him.

One of Scotland's most important cults was that of St Andrew. It started on the east coast at Kilrymont in the 700s. People believed the shrine held the saint's relics. Pilgrims came from all over Scotland, England, and beyond. By the 1100s, Kilrymont was known as St. Andrews. It became linked with Scottish national identity and the royal family. Queen Margaret also became a revered national saint after her death and the moving of her remains to Dunfermline Abbey.

People went on pilgrimages for many reasons. They might do it for personal devotion, as a punishment from a priest, or to seek cures for illness. We know from written records and pilgrim badges that Scots traveled to shrines in Scotland and further away. Popular sites included Jerusalem, Rome, and Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

Scots also took part in the Crusades. Friars preached about crusading, and special taxes were collected. Many Scots joined the First Crusade (1096–99). Large numbers also participated in later crusades, including those led by Louis IX of France. Many died from disease. The crusading ideal remained important for kings like Robert I and James IV.

The Christian calendar shaped community life. Fairs were held at Whitsun and Martinmas. People traded, married, and moved house during these times. The mid-winter season of Yule involved two weeks of celebrations. The feast of Corpus Christi, celebrating the body of Christ, grew in importance. Easter was the most important Christian event. It was preceded by 40 days of fasting during Lent, when people confessed their sins. Most people received communion once a year on Easter Sunday.

Late Medieval Changes

Some historians used to say the late Medieval Scottish church was corrupt. But newer research shows it met people's spiritual needs. Monastic life seemed to decline, with fewer monks in religious houses. Many monks also lived more individual lives.

However, in towns, new groups of mendicant friars became very popular in the 1400s. Unlike older monks, friars focused on preaching and helping ordinary people. The Observant Friars became a Scottish group from 1467.

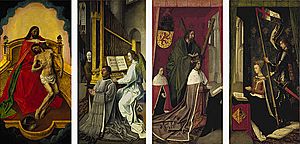

Most Scottish towns had only one parish church. But as the idea of Purgatory became more important, the number of chapels, priests, and masses for the dead grew quickly. These were meant to help souls get to Heaven faster. The number of altars dedicated to saints also increased. For example, St. Mary's in Dundee had about 48 altars, and St Giles' in Edinburgh had over 50.

More saints were celebrated in Scotland. New devotions related to Jesus and the Virgin Mary also arrived in the 1400s. These included devotion to the Five Wounds of Christ and the Holy Name of Jesus. New religious feasts were also added to the calendar.

Ideas like Lollardry, which questioned church teachings, came to Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early 1400s. Lollards followed John Wycliffe and Jan Hus. They wanted church reform and disagreed with some teachings about the Eucharist. Despite some people being burned for heresy, Lollardy remained a small movement in Scotland.

The Reformation Era

The Scottish Reformation in the mid-1500s was a huge change in religious practice. It was strongly influenced by Calvinism. Many old practices were stopped, like confession, using Latin in services, and praying to Mary and the Saints. The idea of Purgatory was also rejected.

Church interiors changed dramatically. The High Altar, altar rails, and statues were removed. Walls were whitewashed to cover old paintings. Instead, churches had a plain table for communion, pews for people to sit, and pulpits for sermons. Sermons became the main focus of worship and could last up to three hours.

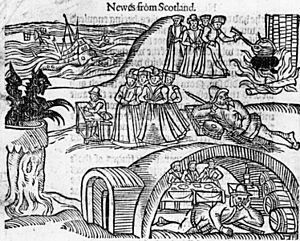

In the late Middle Ages, there were few witchcraft trials. But the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft a crime punishable by death. The first major trials were the North Berwick witch trials in 1589. King James VI was very involved. He even wrote a book defending witch-hunting.

Between 4,000 and 6,000 people were tried for witchcraft in Scotland during this time. This was a much higher rate than in England. Most accused people (75%) were women. Major trials happened in 1590–91, 1597, 1628–31, 1649–50, and 1661–62. It's estimated that over 1,500 people were executed.

Seventeenth Century Faith

In the 1600s, Scottish Protestantism focused heavily on the Bible. It was seen as perfect and the main source of moral guidance. The Geneva Bible was commonly used early on. In 1611, the church adopted the King James Version. Many Bibles were large and valuable. Some people even used them for divination.

Family worship was strongly encouraged. Books of devotion were given out to help families pray together. Ministers checked if families were doing this.

By the mid-1600s, Scottish Presbyterian worship took the form it would keep for a long time. The Westminster Directory was adopted in 1643. This meant Scots followed the English Puritan dislike of set prayers. The Creed, Lord's Prayer, and Ten Commandments were no longer recited. Instead, long sermons became central. The only part people sang was psalms. Later, people would sing psalms by lining out, where a leader sang each line, and the congregation repeated it.

The 1600s saw strong church discipline. Local church courts, called kirk sessions, could punish people. They could stop people from taking communion or being baptized to enforce good behavior. For serious moral issues, they worked with local judges.

Kirk sessions also tried to stop public celebrations like well-dressing, bonfires, and dancing. They also managed poor relief. In 1649, a law said local landowners had to pay to support the poor. This system worked well in the Lowlands for general poverty. But it struggled during major food shortages in the 1690s.

The church also played a big role in education. Laws in 1616, 1633, 1646, and 1696 created a system of parish schools. Local landowners paid for them, and ministers managed them. By the late 1600s, most Lowland areas had schools. But many Highland areas still lacked basic education.

Witchcraft trials were often managed by kirk sessions. They were sometimes used to target superstitious or Catholic practices. The biggest witch hunt was in 1661–62, with about 664 accused witches. After this, trials became less common. Judges had more control, torture was used less, and evidence standards were higher. People also became more doubtful about witchcraft. The last executions were in 1706, and the last trial was in 1727. The British parliament ended the 1563 Act in 1736.

Eighteenth Century Worship

The church had a lot of control over people's lives in the 1700s. It managed poor relief and schools through parishes. It also watched over people's morals. If someone committed a moral offense, they had to "purge their scandal." This meant standing or sitting before the congregation for up to three Sundays. The minister would often scold them. Sometimes, there was a special repentance stool near the pulpit. In some places, people even wore sackcloth.

From the 1770s, private scoldings became more common, especially for wealthy men. But poor people were almost always publicly rebuked until the 1820s. Early in the century, the church tried to stop dancing and events like penny weddings. But this control over secular music and dancing began to ease around 1715–1725.

From the mid-1700s, people argued that lining out psalms should stop. Instead, they wanted to sing psalms stanza by stanza. Later, this led to a choir movement. Schools were set up to teach new tunes and singing in four parts.

Among Episcopalians, some chapels used the English Book of Common Prayer. They had organs and musicians, like English churches. Catholic worship was kept quiet, often in private homes. Chapels from this time were simple. Worship usually included a sermon, long prayers, and Low Mass in Latin. Music was not allowed until the 1800s, when organs were introduced.

Communion was the most important church event. It was held rarely, usually once a year. People had to be tested by a minister and elders on their knowledge of the Westminster Shorter Catechism. Then they received communion tokens to take part. Long tables were set up in the church for people to sit at during communion. If ministers didn't offer communion in their parish, large outdoor gatherings were held. These "holy fairs" often combined several parishes. The church discouraged them, but they continued. They could mix with secular activities and were even written about by Robert Burns in his poem Holy Fair.

Nineteenth Century Changes

The population grew quickly in the late 1700s and early 1800s, especially in cities. This strained the parish system of the church. Many workers in cities felt disconnected from organized religion. The church tried to build more churches in new towns and the Highlands. By the early 1840s, 222 new churches had been added. These new churches mostly attracted middle-class people and skilled workers. But many poor people could not afford the pew rents and remained outside the church system.

Industrialization, city growth, and the Disruption of 1843 weakened the tradition of parish schools. To help, Sunday schools were started. Town councils began them in the 1780s, and all churches adopted them in the 1800s. By the 1830s and 1840s, these expanded to include mission schools, ragged schools, and Bible societies. These were open to all Protestants and aimed at city workers. By 1890, Baptists had more Sunday schools than churches, teaching over 10,000 children.

The old system of poor relief, managed by the church, broke down in cities. After the Disruption in 1845, control of poor relief moved from the church to local boards. But the help provided was still not enough for the scale of poverty.

The temperance movement, which encouraged people to avoid alcohol, came from America in 1828–29. By 1850, it was a main part of the church's work with the working classes. New temperance groups formed, including the Independent Order of Good Templars. The Salvation Army also promoted sobriety. The Catholic Church had its own temperance movement and worked with Protestant groups. Other religious groups like the Orange Order and Freemasonry also grew.

A "liturgical revival" happened in the late 1800s. It was influenced by the English Oxford Movement. This encouraged a return to older church architecture and worship styles. Accompanied music was brought back into the Church of Scotland. Sermons became shorter, and there was more focus on the church calendar.

The Church Service Society was founded in 1865 to promote worship reform. A year later, organs were officially allowed in Church of Scotland churches. Many churches added organs and choirs. However, some conservative members still opposed them. In the Episcopalian Church, more traditional services became common. The Free Church was more cautious about music, not allowing organs until 1883.

Hymns were first used in the United Presbyterian Church in the 1850s. They became common in the Church of Scotland and Free Church in the 1870s. The visit of American evangelists Ira D. Sankey and Dwight L. Moody in 1874–75 helped make accompanied church music popular. Sankey made the harmonium so popular that working-class churches wanted music. The Moody-Sankey hymn book remained a bestseller.

Twentieth Century Religion

Church attendance in Scotland declined after World War I. Some reasons suggested include the rise of the nation-state, socialism, and science. By the 1920s, about half the population was connected to a Christian church. This level stayed until the 1940s, when it dipped during World War II. It increased in the 1950s due to revival campaigns, especially Billy Graham's 1955 tour. But after that, there was a steady decline, speeding up in the 1960s. By the 1980s, only about 30% attended church. This decline affected cities and skilled workers most. Catholic church attendance stayed higher than Protestant ones.

Sectarianism became a serious problem in the 1900s. Tensions between Protestants and Catholics grew during the economic depression. The Orange Order, mainly Irish Protestants, became a center for anti-Catholic feelings. They held parades that sometimes led to riots. Leaders of some Protestant churches also campaigned against Catholic Irish immigrants. This created an atmosphere of intolerance.

After World War II, the church became more open-minded. But sectarian attitudes continued in football rivalries. This was most clear in Glasgow, between the Catholic-linked team, Celtic, and the Protestant-linked team, Rangers. While Celtic hired Protestant players, Rangers traditionally did not recruit Catholics. This changed when Rangers signed Catholic player Mo Johnston in 1989 and appointed their first Catholic captain, Lorenzo Amoruso, in 1999.

At the same time, churches began to work together more. The Scottish Council of Churches was formed in 1924 to promote ecumenical unity. The Catholic Church in Scotland formalized hymns with The Book of Tunes and Hymns (1913). The Iona Community, founded in 1938 on the island of Iona, created very influential church music. John Bell adapted folk tunes for spiritual songs.

Recent Religious Trends

Relations between Scotland's churches continued to improve in the late 1900s. There were many efforts for cooperation and unity. Proposals in 1957 for union with the Church of England were rejected. The Scottish Episcopal church allowed all baptized Christians to take communion.

The Dunblane consultations (1961–69) were informal meetings at the Scottish Church House. They aimed to create modern hymns that were still theologically strong. This led to a "Hymn Explosion" in the 1960s, producing many new hymn collections.

In 1990, the Scottish Churches' Council was replaced by Action of Churches Together in Scotland (ACTS). This group tried to bring churches together for work in prisons, hospitals, and social projects. The Scottish Churches Initiative for Union (SCIFU) tried to unite several churches, but this was rejected in 2003.

The decline in religious connection continued into the 2000s. In the 2001 census, 27.5% of people said they had no religion. In the 2011 census, about 54% identified as Christian, and 36.7% said they had no religion. Other studies suggest the number of non-religious people might be even higher.

In recent years, other religions have grown in Scotland. This is mainly due to immigration and higher birth rates among ethnic minorities. These religions include Islam (1.4%), Hinduism (0.3%), Buddhism (0.2%), and Sikhism (0.2%) in the 2011 census. Other smaller faiths include Judaism, the Bahá'í Faith, and small Neopagan groups. There are also groups that promote humanism and secularism.

Images for kids

-

The Monymusk Reliquary, or Brecbennoch, said to house the bones of Columba

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |