Siege of Leith facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Leith |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the European wars of religion | |||||||

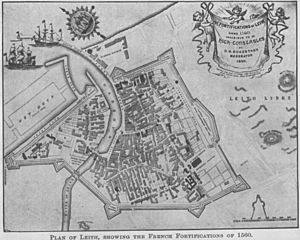

Map of the siege of Leith dated 7 May 1560 from Petworth House |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Queen Mary of Guise Henri Cleutin Sébastien de Luxembourg Jacques de la Brosse |

James Hamilton William Grey James Croft William Winter |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| French soldiers in Leith (28 May 1560): 2,300; others 2,000 French evacuated from Scotland in July 1560: 3,613 men, 267 women, 315 children |

English total (25 May 1560): 12,466 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7 May 1560: 15 | 7 May 1560: English: 800 Scottish: 400 |

||||||

The siege of Leith was a big event in 1560 that ended a long stay of French soldiers in Leith, a port town near Edinburgh, Scotland. The French had been invited to Scotland in 1548. They finally left in 1560 after English forces arrived to help remove them. The town was not captured by fighting. Instead, the French soldiers left peacefully under a special agreement called a treaty. This treaty was signed by Scotland, England, and France.

Why the Siege Happened

Old Friends and New Religions

For a long time, Scotland and France were close allies because of something called the "Auld Alliance" (meaning "Old Alliance"). This friendship started way back in the 1200s. But in the 1500s, things changed. People in Scotland started to disagree about religion. Some wanted to stay Catholic, like France. Others became Protestants, following new ideas about Christianity.

These Protestants saw the French as a strong Catholic influence in Scotland. When fights broke out between the two religious groups, the Protestants asked their English neighbours for help. England was also Protestant at this time. They wanted the French to leave Scotland.

In 1542, the Scottish King, James V, died. He left behind a baby daughter, who became Mary, Queen of Scots. James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, was chosen to rule Scotland until Mary grew up. He first agreed that baby Mary should marry the English King's son, Edward. But Mary's mother, Mary of Guise, and a powerful church leader, Cardinal Beaton, changed his mind. Arran then arranged for Mary to marry François, the French prince.

The "Rough Wooing" War

King Henry VIII of England was very angry that the Scots broke their promise. So, he started a war against Scotland from 1544 to 1549. This period was later called the "Rough Wooing" because England was trying to force Scotland into marriage with England.

In May 1544, an English army landed near Leith. They captured Leith to bring in big cannons for an attack on Edinburgh Castle. But they left after burning Leith and the Palace of Holyrood. Three years later, after another English victory at the Battle of Pinkie, the English tried to control parts of Scotland. Leith was very important because it was Edinburgh's main port. It handled all the city's trade and supplies.

French soldiers arrived in Leith in June 1548 to help Scotland. There were about 8,000 of them. The young Queen Mary was then sent to France for safety. By the end of 1549, most English troops had left Scotland.

Over the next few years, France became very powerful in Scotland. More and more French soldiers were stationed in places like Haddington and Leith. From 1548, work began to make Leith's port stronger. They built new forts and walls. These were designed in a new style called trace italienne, which was very good at defending against cannons. In 1554, Mary of Guise, Mary Queen of Scots' mother, became the ruler of Scotland. She continued to support France and put French people in important jobs.

The Religious Problem

Meanwhile, the Scottish Protestants became more and more unhappy. Especially after Mary married the French prince in 1558. A group of Scottish noblemen, called the Lords of the Congregation, became leaders of the anti-French, Protestant group. They joined forces with John Knox and other religious reformers. They gathered 12,000 soldiers to try and force the French out of Scotland. Even the Earl of Arran, who used to be Regent, joined the Lords of the Congregation.

In 1559, the Lords of the Congregation controlled most of central Scotland. They entered Edinburgh, forcing Mary of Guise to hide in Dunbar Castle. But with the help of 2,000 French soldiers, she took back control of Edinburgh. A short peace agreement, called the Articles of Leith, was made in July 1559.

Mary of Guise received more military help from France. The Lords of the Congregation saw this as breaking the peace agreement. They said the French were making Leith stronger to kick out the local people and bring in French families. Mary of Guise said she was only making Leith safe for herself and her soldiers because the Lords were planning to attack Edinburgh. She said the French had not brought their families.

The Lords of the Congregation then removed Mary of Guise from her role as ruler. They asked the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I of England for military help. Elizabeth sent the Duke of Norfolk to lead an army. He met the Scottish leaders and signed the Treaty of Berwick. This treaty meant England now officially supported the Lords of the Congregation against the French in Scotland.

The Siege Begins

Getting Ready for the Fight

The French army kept making Leith's forts even stronger in late 1559. The defenses included eight strong, sticking-out parts called bastions. These included Ramsay's Fort, which protected the harbour. Inside the walls, there was a raised platform for cannons, called a "cavalier."

In January 1560, an English fleet, led by William Wynter, arrived in the Firth of Forth. English diplomats pretended Wynter's arrival was an accident. The ships were sent by Queen Elizabeth's advisor, William Cecil.

After the Treaty of Berwick, England planned to bring its army and cannons to Leith. It was hard to move heavy equipment by land in winter. So, they decided to send most of the soldiers and cannons by sea. An army of about 6,000 English soldiers, led by Lord Grey de Wilton, marched from Berwick. They arrived in early April to join the Scottish Lords. Lighter cannons for the siege were brought by ship to a nearby port. Before the English army arrived, the French attacked Glasgow and Linlithgow. The French soldiers from Haddington also moved into Leith, making their numbers about 3,000.

Mary of Guise and her advisors stayed safe in Edinburgh Castle. The castle's keeper said it was neutral, so it didn't take part in the fighting.

First Clash at Restalrig

Lord Grey of Wilton set up his camp at Restalrig village on April 6, 1560. He tried twice to talk with Mary of Guise and the French commander, Henri Cleutin. But they refused. Cleutin said his soldiers were on their own land.

Soon after, fighting started at Restalrig. French soldiers on horseback, called arquebusiers (who used early guns), chased an English group. They were killed or captured near the sea. More than 100 French soldiers were hurt, and 12 officers were killed. The French were trying to take control of the high ground south of Leith.

Building Forts: Mount Pelham

The English started building their siege forts against Leith in mid-April. One important fort was "Mount Pelham," named after William Pelham, who led the workers. This fort faced the eastern side of Leith. Mount Pelham was a strong fort with four corner towers. It was meant to help attack the town.

While the English were building, the French also built their own small forts outside Leith's main walls.

The Big Cannon Attack

The English had brought some small cannons. On April 10 and 11, the big siege cannons arrived. On April 12, the French heard a rumour that the English thought they didn't have enough weapons. So, the French fired all 42 of their cannons, killing 16 in the English camp.

On Sunday, April 14, Easter day, the big English cannons were ready. The English started firing their cannons from the west and south of Leith. The French fired back from St Anthony's church steeple and other strong points.

Mount Pelham Attacked

The next day, April 16, about 1,200 French soldiers attacked the English fort at Mount Pelham. They captured four cannons and killed 200 English soldiers. The French were eventually pushed back. About 150 soldiers were killed on both sides.

Some people said a Scottish woman helped the French by signalling to them from a hill. This story might refer to the hills on Leith Links called "Giant's Brae" and "Lady Fyfe's Brae."

Later, on June 18, 300 French soldiers attacked Mount Pelham again. But they were chased back to Leith by English soldiers. Forty French soldiers were killed.

More Forts: Mount Somerset and Mount Falcon

At the end of April, the English built more forts to the west. A new fort called "Mount Somerset" was built. The work continued further west and north, across the Water of Leith river. Here, more cannon positions were set up. "Mount Falcon" was built after May 7, 1560. It could fire at the houses along the Leith quayside.

The English forts stretched for about 1 mile around Leith. They had six cannon positions about 500 yards from Leith's walls. Mounts Pelham and Somerset were large temporary forts with walls up to 13 feet high. Besides soldiers, there were many workers building these forts.

May 7: A Tough Day for the English

Queen Elizabeth and her advisor, William Cecil, wanted the siege to end quickly. So, they pushed the English commanders for results. The English planned to attack Leith before dawn on May 7. They would attack in two waves with thousands of men. English ships would also land 500 soldiers inside the town.

On May 1, there was an accidental fire in Leith. The English started firing their cannons at the western walls. But the French quickly repaired the damage. The English commander, Grey, worried that the town looked even stronger.

The attack was set for 4:00 AM on Tuesday, May 7. But the English were defeated. Even though they made two holes in the walls, the damage wasn't enough. The French cannons were still working, and the English ladders were too short. The English and Scottish forces suffered heavy losses, with estimates ranging from 400 to 1,500 killed. The French said only 15 of their defenders died.

According to John Knox, a Scottish reformer, Mary of Guise watched the battle from Edinburgh Castle. She was happy about the French victory. She supposedly compared the English dead lying on Leith's walls to beautiful tapestries laid out in the sun.

Secret Messages and Tunnels

After the English defeat, talks for peace started again. But the siege continued. The English brought experts from Newcastle upon Tyne to dig tunnels, called mines, towards Leith's forts.

Mary of Guise, who was very sick, sent a letter to the French commander asking for medicine. Lord Grey of Wilton, the English commander, was suspicious. He held the letter over a fire and found a secret message written in invisible ink. The French journal of the siege says the secret message was about the English plans.

Coded letters were also carried out of Leith by a drummer. An English officer managed to figure out one of the French codes. Mary of Guise sent coded letters to her commanders, telling them where the English were digging tunnels. But these letters were captured and decoded by the English.

By June 18, after Mary of Guise died, the French in Edinburgh Castle realized their code was known to the English. They told the Leith soldiers to keep using the code in letters that might be captured. This was to spread false information during the peace talks. This coded letter was also caught and decoded by the English.

Hunger in Leith

After the failed attack on May 8, the English commander, Grey, thought he could starve out the French soldiers in Leith. He said there was already "great scarcity" (not enough food) inside the town. The French kept trying to leave the town to find food, even though their supplies were running low. The English, however, received more soldiers and food.

Grey said his men killed 40 or 50 French soldiers and others who came out of Leith to gather shellfish like cockles and periwinkles on May 13. A little French boy caught on the shore was brought to Grey. When asked about food, the boy said the French captains believed the English wouldn't take the town by hunger or force for another four or five months.

One English prisoner in Leith described how the people and soldiers were so hungry they ate horses, dogs, cats, and even insects. They also ate leaves, weeds, and grass, which they called "dainties" because they were so hungry.

On May 28, it was reported that the French had no meat or drink except water for three weeks. They only had bread and salted salmon. These were given out in small amounts: 126 ounces of bread per man each day and one salmon for six men each week. There were about 2,300 French soldiers and over 2,000 other people in Leith.

After Mary of Guise died, a week-long ceasefire was called on June 17. On June 20, French and English soldiers ate together on the beach. The English brought good food like beef, chicken, wine, and beer. The French brought cold roasted chicken, a horse pie, and six roasted rats.

The Treaty of Edinburgh

After the English defeat on May 7, peace talks started again. But they failed because the French commanders in Leith were not allowed to meet Mary of Guise at Edinburgh Castle. New talks began in June. Important people from France and England arrived in Edinburgh. But they found that Mary of Guise, the ruler of Scotland, had died at Edinburgh Castle on June 11.

Her death made the French soldiers lose hope. The peace negotiators agreed to a week-long ceasefire on June 17. The fighting ended on June 22, with only one small fight on July 4. Peace was agreed shortly after and announced on July 7.

This peace agreement became known as the Treaty of Leith or the Treaty of Edinburgh. It meant that both French and English soldiers had to leave Scotland. It also effectively ended the "Auld Alliance" between Scotland and France. By July 17, all the foreign soldiers had left Edinburgh. A total of 3,613 French men, 267 women, and 315 children were sent from Scotland to France. The treaty allowed 120 French soldiers to stay in two other places, but the forts in Leith had to be destroyed right away. The English soldiers started destroying Leith's defenses on July 15.

A very important part of the treaty was that the French King and Queen, François and Mary, had to stop using the title and symbols of the King and Queen of England. As Catholics, they believed Elizabeth was not the rightful Queen of England. So, Mary believed she was the true Queen. Their use of the English royal symbols led the French to call this conflict the "War of the Insignia." Queen Mary never officially agreed to this part of the treaty, because it would mean she accepted Elizabeth as the rightful Queen of England.

After the French left, Edinburgh's town treasurer paid to clean up the Leith Shore. A ship that the French had sunk to block the harbour was pulled out of the water. Two hundred Scottish workers were busy removing the forts.

What We Remember

The "School of War"

This siege was the first big military conflict during Queen Elizabeth's rule. So, writers at the time called it the "School of War." One writer, Thomas Churchyard, wrote a poem about the siege using this title. He wrote about a Scottish woman who signalled to the French from a rock before the English defeat on May 7, 1560.

Churchyard also wrote that the French tried to attack Mount Pelham while dressed as serving women.

Old Forts and New Discoveries

There is still a lot of evidence of the forts built by the French and the cannon positions built by the English. New examples were found in 2001, 2002, and 2006. The place where the Mount Falcon cannon was is marked by a plaque. The two hills on Leith Links, called "Giant's Brae" and "Lady Fyfe's Brae," are now protected historical sites.

The walls of Leith were ordered to be destroyed after the siege. But it took a while. Some parts of the walls were repaired later in 1572 during a civil war in Scotland. In 1594, rebels against the Scottish King also repaired the forts.

In 1639, it was reported that Scottish women were working hard to build up the walls in Leith. This was unusual, as women rarely did such heavy manual work on building sites in Scotland.

A part of the walls and a fort called the Citadel were rebuilt in 1649 during another war. These new forts were held by supporters of Charles II of England. In the 1800s, new streets like Great Junction Street and Constitution Street were built along the lines of the old southern and eastern walls.

See also

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |